As we reflect on the bicentennial of modern Singapore this year, we should not forget another significant milestone in our nation's history: Singapore's achievement of internal self-government in June 1959. This year marks its 60th anniversary.

To commemorate 60 years of self-rule, this graphic spread presents 60 objects from Singapore's various National Collections which, when taken together, provide a sweeping overview of the story of Singapore from the late first millennium, through the colonial period to the present.

The objects presented here are curated along five key sections:

A) Networks through Time, B) Colonial, C) Community and Faith, D) Art Historical, and E) Self-Government and Independence.

The narrative does not follow a simple chronology of key milestones in Singapore's history, but instead opts for a more complex, networked, hybrid approach blending chronology, geography, cultures and major themes.

60 objects

In choosing the objects to be included, I have been guided by the following criteria:

a) that these be objects in collections owned by publicly-funded national institutions in Singapore;

b) that these be masterpieces of art, or pieces of historical and socio-cultural significance, with a particular focus on pieces representative of significant collections of objects in public holdings;

c) that the graphic spread as a whole is community-inclusive, by which I mean representing all ethnic communities and faiths in Singapore, with a particular effort made in representing the voices of women;

d) that the spread be genre-inclusive, by which I mean representing a diverse variety of object types and art genres;

e) that the spread places Singapore in the larger global, Asian and Southeast Asian context, emphasising that Singapore, and Singapore’s history, does not exist in a vacuum, but has always been open to and impacted by developments in the regional and global spheres; and finally,

f) that the objects chosen are on physical display, as far as possible, in the permanent galleries of the institutions from which they come.

This story of Singapore told through 60 objects is thus unique, in that it is global, cross-cultural, multi-faith and inclusive, by which I mean it includes collections beyond the National Collection held by the National Heritage Board and displayed at the National Museums and Art Galleries. The narrative presented here also reaches back further than the now widely-accepted 700-year timeline of Singapore history. The goal of this spread is ultimately to defamiliarise; to allow our readers to see that Singapore history is rich and multi-dimensional, and that as a nation and a people, we possess a wonderful treasure trove in our museums, archives and libraries that we should preserve, cherish and celebrate.

A) Networks through Time

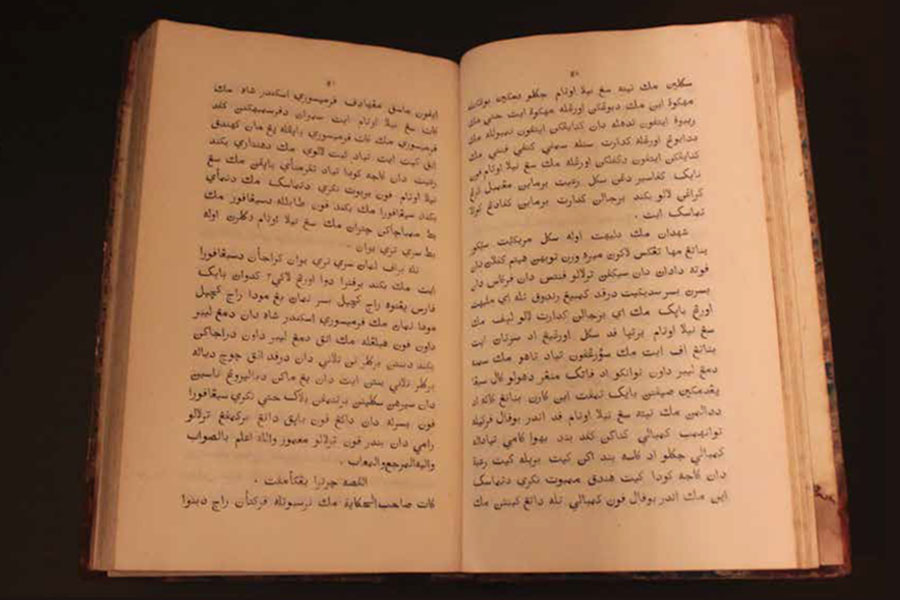

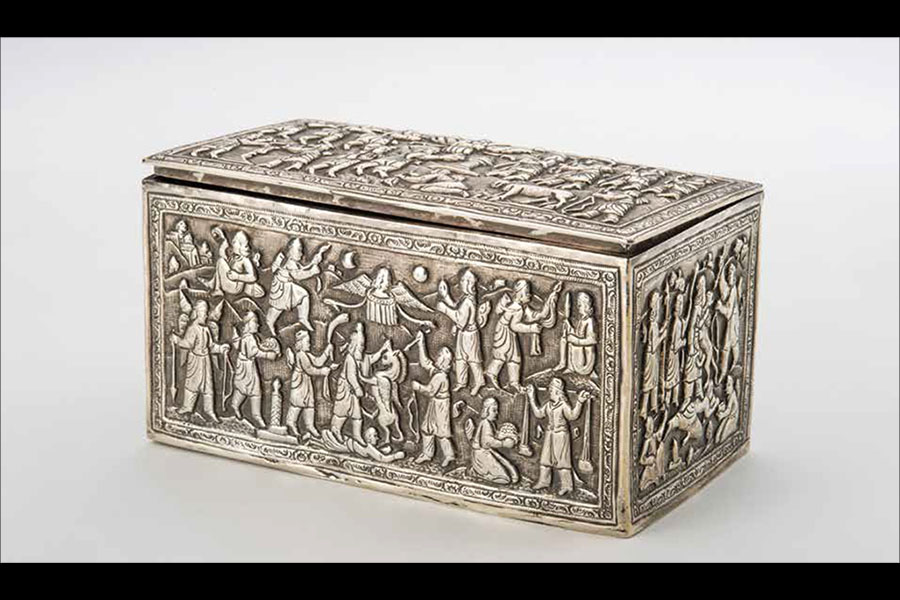

Situated at the midway point between China and India, Southeast Asia has been at the crossroads of maritime trade since the late first millennium. The Tang Shipwreck, excavated off the island of Sumatra, is testament to large-scale intra-Asian maritime trade taking place at least from the 9th century. At the same time, archaeological digs at Fort Canning and around the Singapore River provide evidence that Singapore in the 14th century was already a thriving trading settlement. There are also corroborating accounts in the Sejarah Melayu (The Malay Annals) of a Kingdom of Singapura paying tribute to the Majapahit Empire.

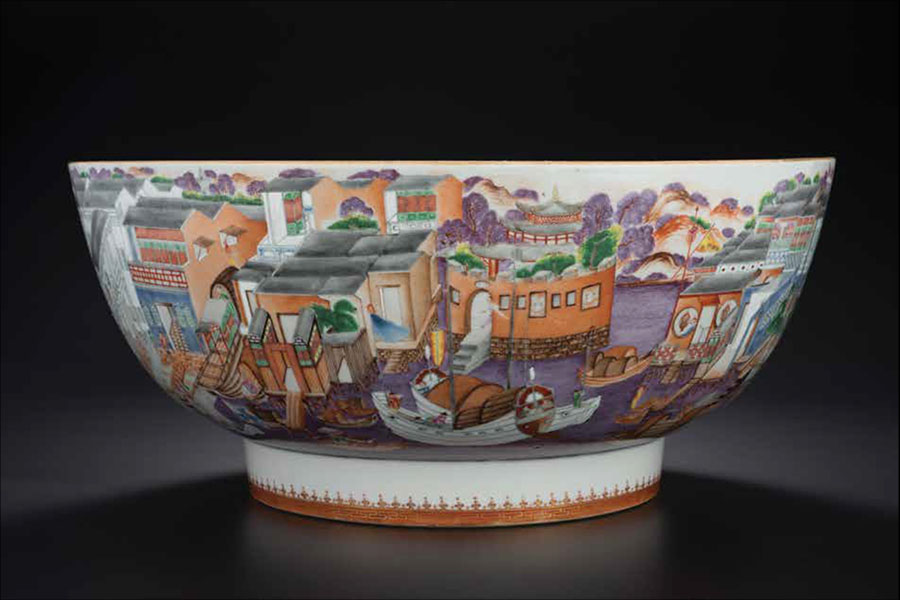

From the 15th century, Southeast Asia takes centrestage in a global tussle among the European imperial powers to secure a monopoly on spices, and thereafter, on luxury goods from the East, in particular Chinese export porcelain and Indian trade textiles such as those in the (former) Hollander Collection of Indian Trade Cloth. Singapore’s heritage as a cosmopolitan, East-West Asian port city has its antecedents in earlier port cities like Malacca (Melaka), Batavia (Jakarta), Manila, Canton (Guangzhou) and the cities of the former Coromandel Coast (corresponding in geography to today's Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh states), from which these luxury goods from the East were exported to the rest of the world.

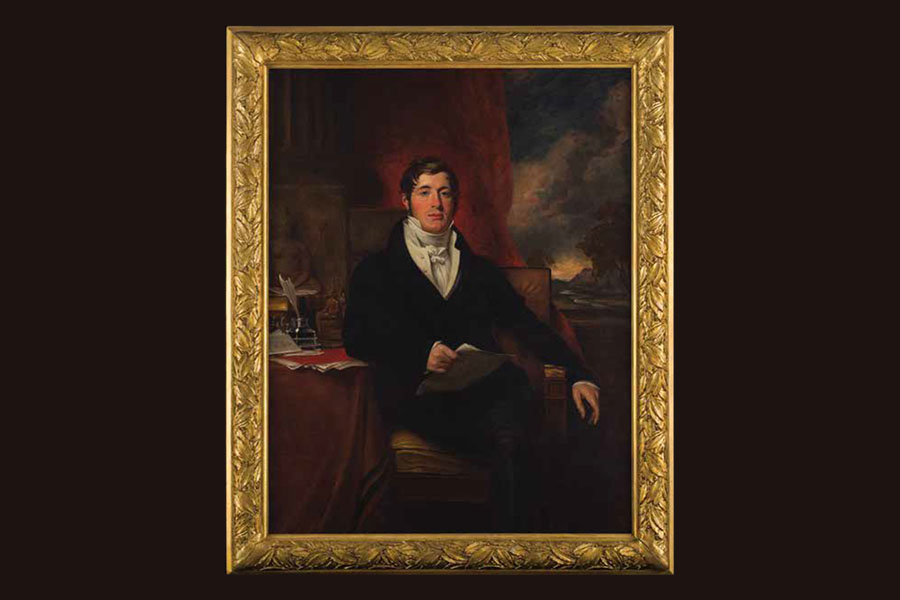

Amidst this theatre of trade, war and colonialism came (English) East India Company operative, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, whose failed bid to secure the island of Java as a British colony became the impetus for his renewed search for a permanent British settlement in the lands (and seas) of the Johor-Riau-Lingga Sultanate.

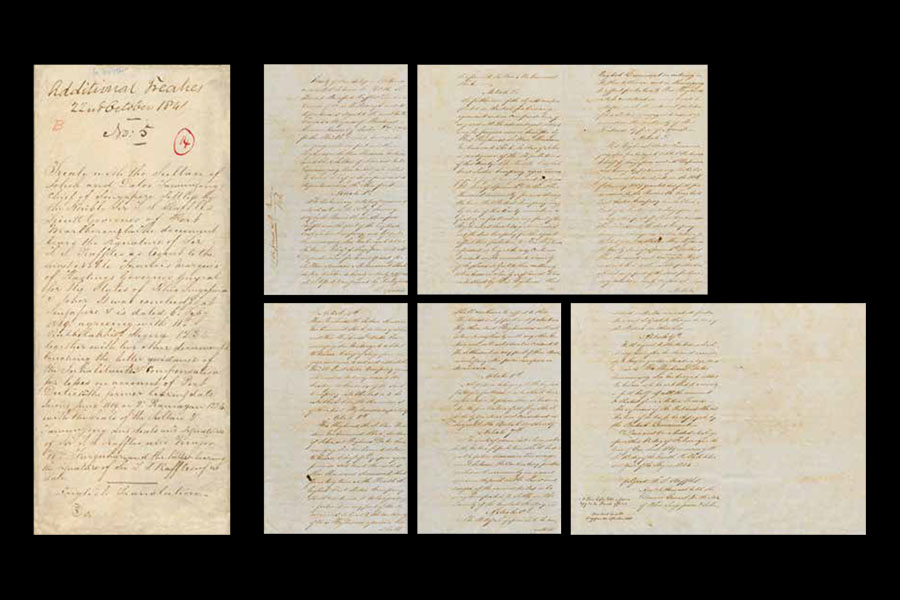

B) Colonial

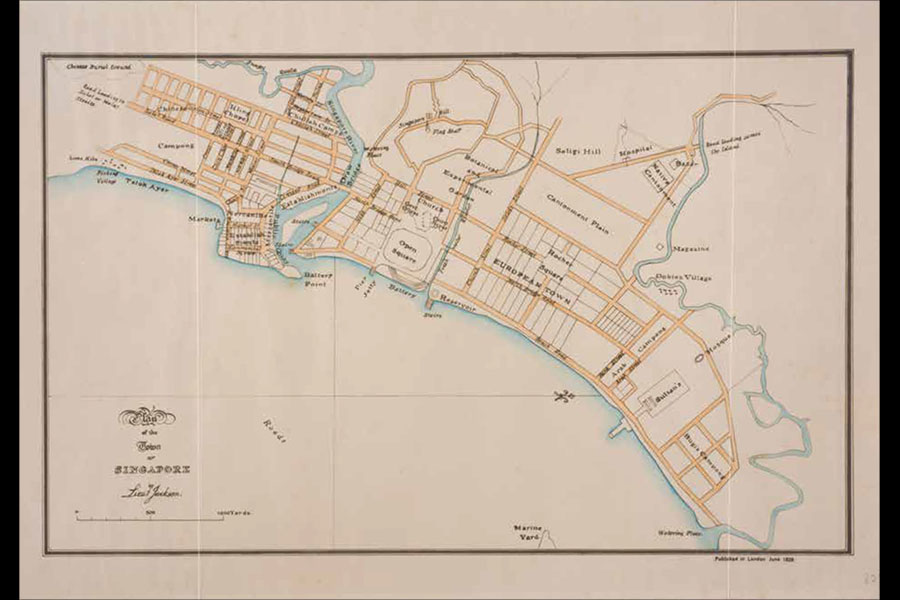

The British settlement and colony of Singapore was established by treaty between Raffles, Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman. The signing of this treaty resulted in the division of the larger Johor-Riau-Lingga Sultanate, a powerful maritime kingdom, of which Singapore was once part of. William Farquhar, who was appointed as the first Resident, spent more time than Raffles in Singapore, and did more for the fledgling colony in his initial years. Singapore thrived through free trade and drew a cosmopolitan resident population from all across Asia and beyond.

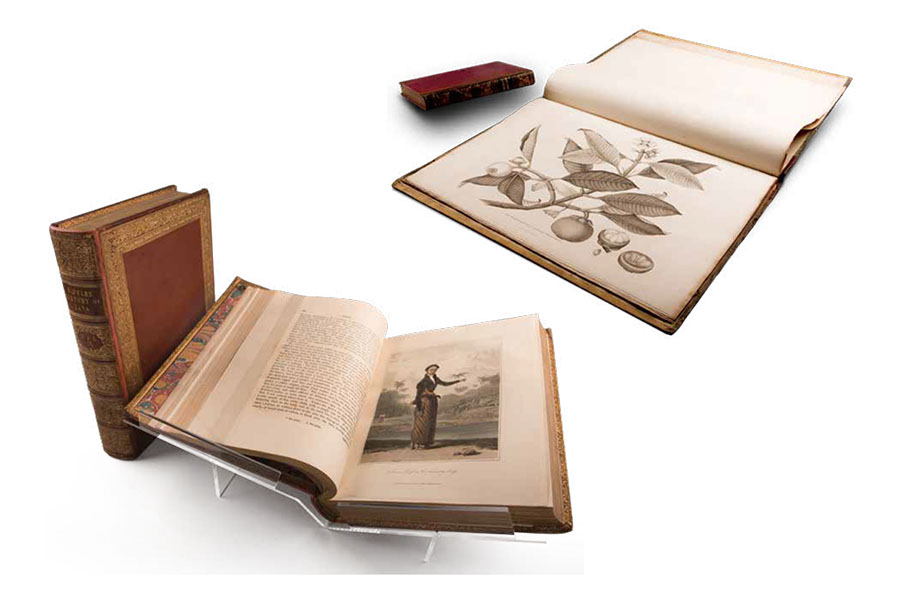

In the course of the century and half that the British were in Singapore and Southeast Asia, they invested in surveying and collecting the region's natural history and cultural heritage, amassing large quantities of artefacts, specimens and drawings that were deposited at the former Raffles Library and Museum (today's National Museum of Singapore), established in 1887. The museum also plays host today to the much older William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings, commissioned by Farquhar himself in the early 1800s.

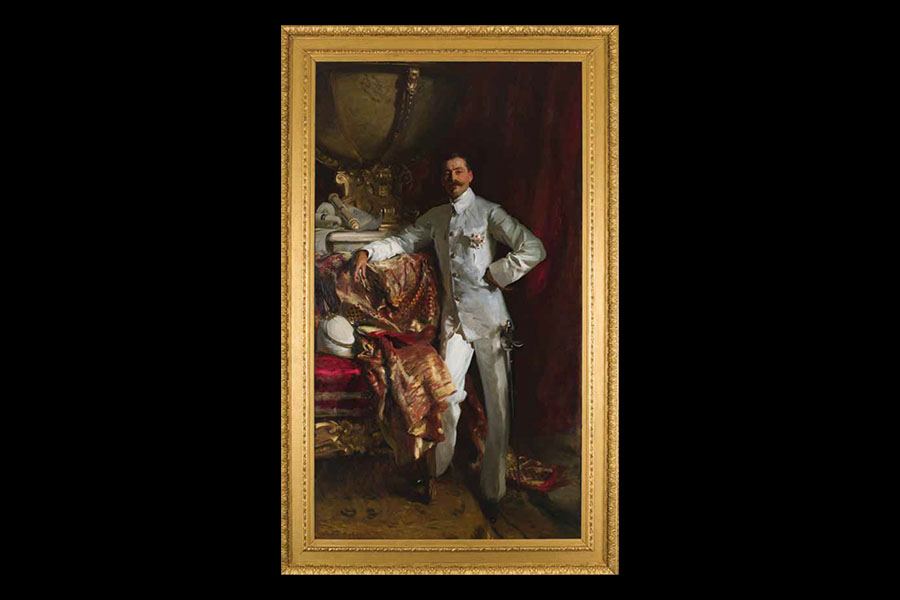

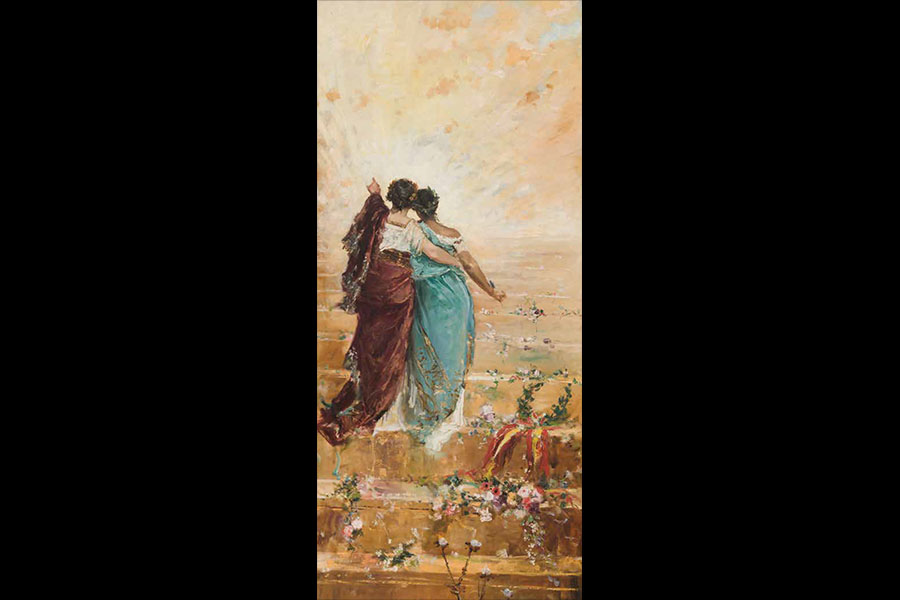

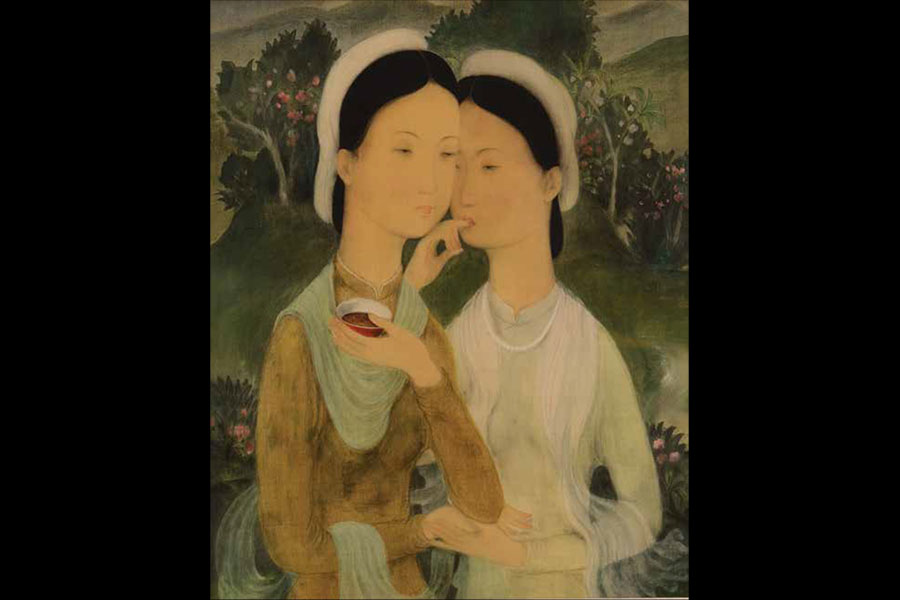

Southeast Asia during the colonial period of 19th to mid-20th centuries was divided and occupied by various European imperial powers: primarily the British in Singapore, Malaya, Burma (today's Myanmar) and North Borneo; the Dutch in the former Netherlands East Indies (today's Indonesia); the Spanish in the Philippines and the French in the former Indochina (today's Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos). The uneasy tension between colonial power and local agency is captured vividly in signature works of major Southeast Asian artists at the turn of the 19th century. This tension would fuel independence movements in the region post-World War II.

But for the time being, Singapore prospered as the foremost trading port in Southeast Asia. The advent of steam-ship and eventually air travel also established Singapore as a pre-eminent tourism destination in Asia, with the Raffles Hotel symbolising the grandeur and opulence of the East. The 1940s and '50s saw Singapore endure the atrocities of the war, the Japanese Occupation, and the aftermath. It was conferred City status in 1951.

C) Community and Faith

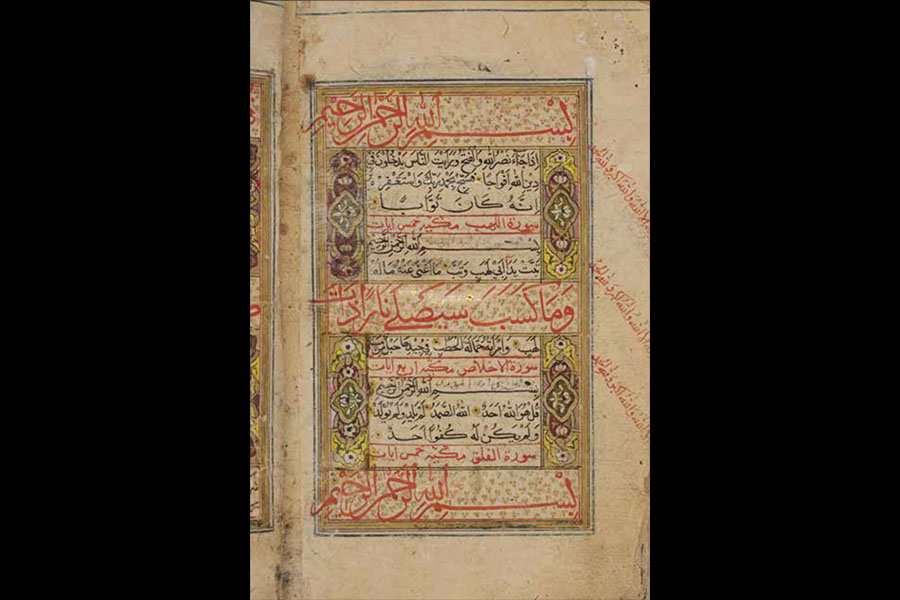

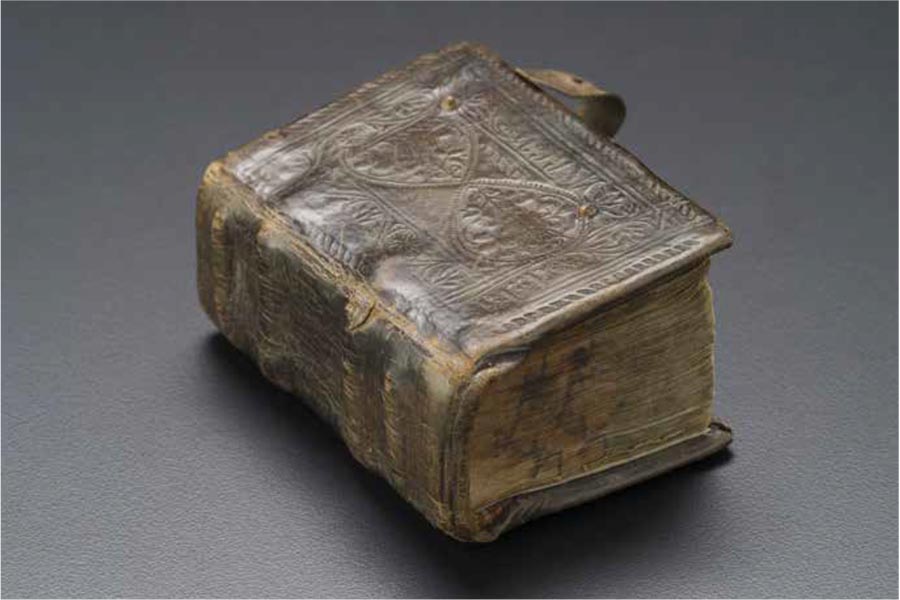

Multi-culturalism is a core facet of Singaporean identity and society. As a pre-eminent trading port in Southeast Asia, Singapore attracted, in the course of its history, ethnic and religious communities from all over Asia and Europe. Aside from the Malay, Chinese, Indian, Eurasian and various Peranakan communities—these ethnicities being themselves convenient amalgamations of many different sub-ethnicities—Singapore also welcomed Arabs, Jews, Armenians and Europeans.

Another important core facet of Singaporean identity and society is religious harmony, with Singapore being the most religiously diverse nation in the world. Singapore's Inter-religious Organisation today recognises 10 world religions in Singapore—the Baha'i faith, Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Jainism, Judaism, Sikhism, Taoism and Zoroastrianism.

This section attempts to capture and present the cultural and religious diversity of Singapore, with all ethnicities and faiths represented as far as possible. Alongside masterpieces of sacred art, material culture features strongly, with film culture being represented by the Cathay-Keris Malay Classics Collection, which was inscribed into the UNESCO Memory of the World Asia-Pacific Register (2014). In the spirit of inclusiveness, particular effort has also been made to feature the stories of women in the community.

D) Art Historical

A proper art history of Singapore in the context of the Southeast Asian and larger Asian region would require its own full graphic spread of 60 objects. As such, this section zooms in on Singapore alone, featuring primarily Singaporean artists—one artist from the Singaporean diaspora in the United Kingdom, one pioneer Singaporean art collector, and one Chinese artist who loved Singapore.

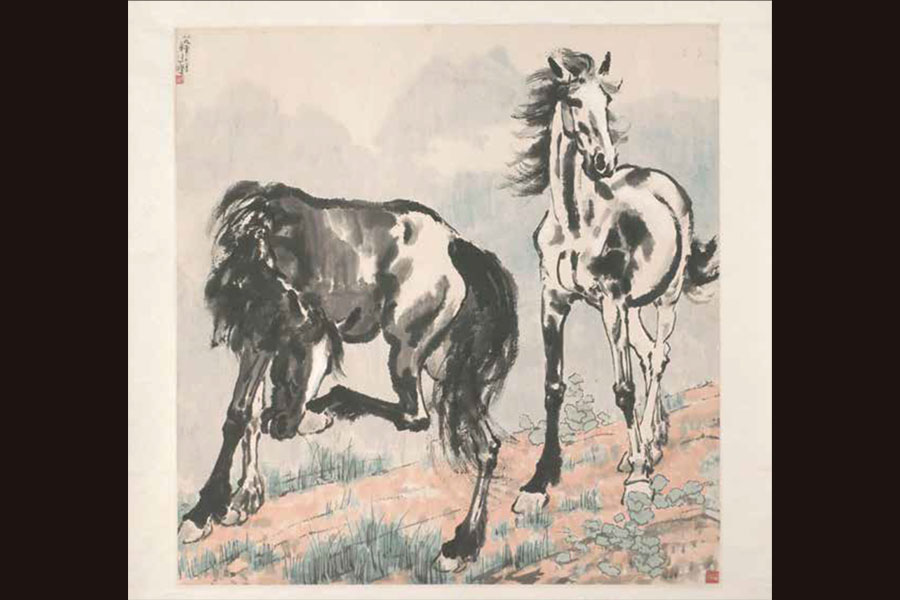

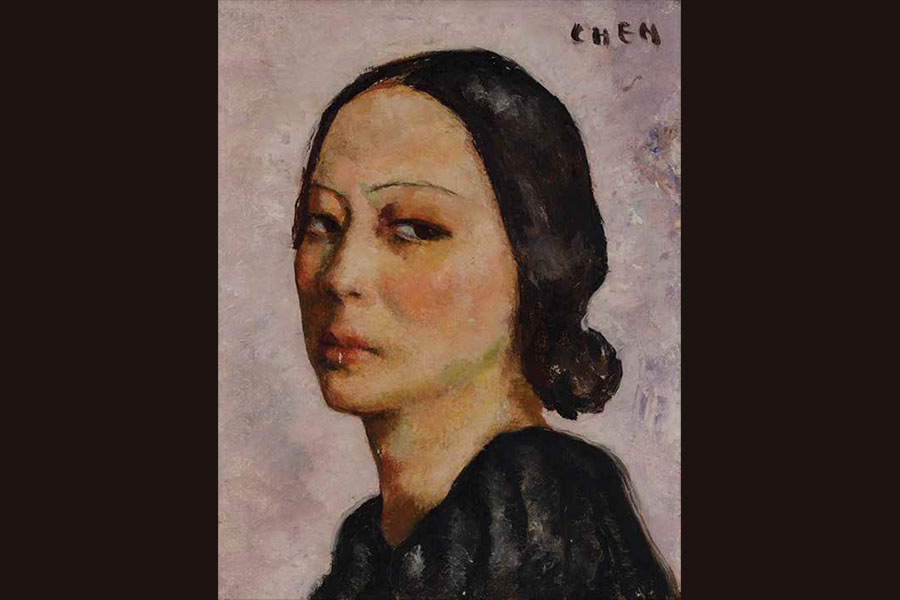

An art history of modern Singapore generally commences with the Nanyang Artists, a seminal group of Singaporean painters represented by the quartet of Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng, and the enigmatic Georgette Chen. They were distinguished by their strong affiliation with the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and by their works, which fused elements of East and West in a distinctive "Nanyang" (Southern Seas) style.

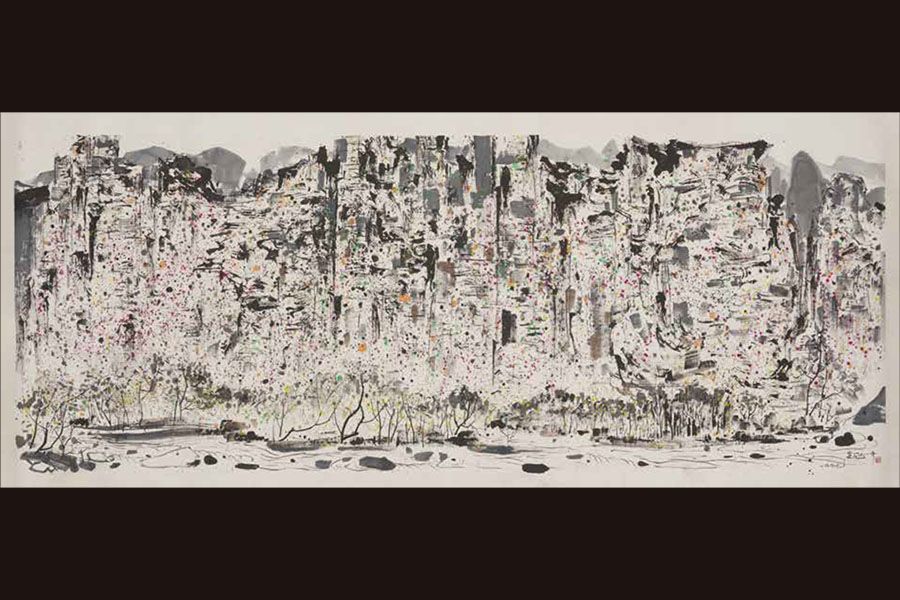

The Nanyang Artists were influenced in turn by major Chinese artists of the early 20th century such as the likes of Xu Beihong, Qi Baishi, Pu Ru, Ren Bonian, Wu Changshuo. A significant collection of these latter artists' works was built up in the 1930s to 1950s by a pioneering local merchant and philanthropist, the late Dr Tan Tsze Chor, also known as the "pepper king". Part of the collection, known as the Xiang Xue Zhuang Collection, was generously given to the state by Tan's family in the 2000s. Around the same period, modern Chinese painter, Wu Guanzhong, regarded as one of the most important modern Chinese painters today, also bequeathed a large gift of his artworks to the National Collection, as a gesture of his strong affection for Singapore.

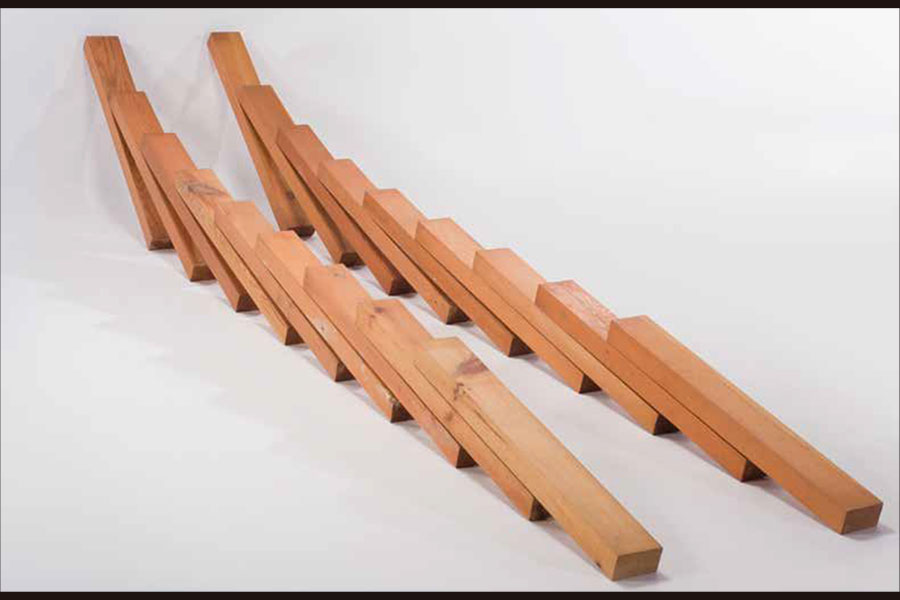

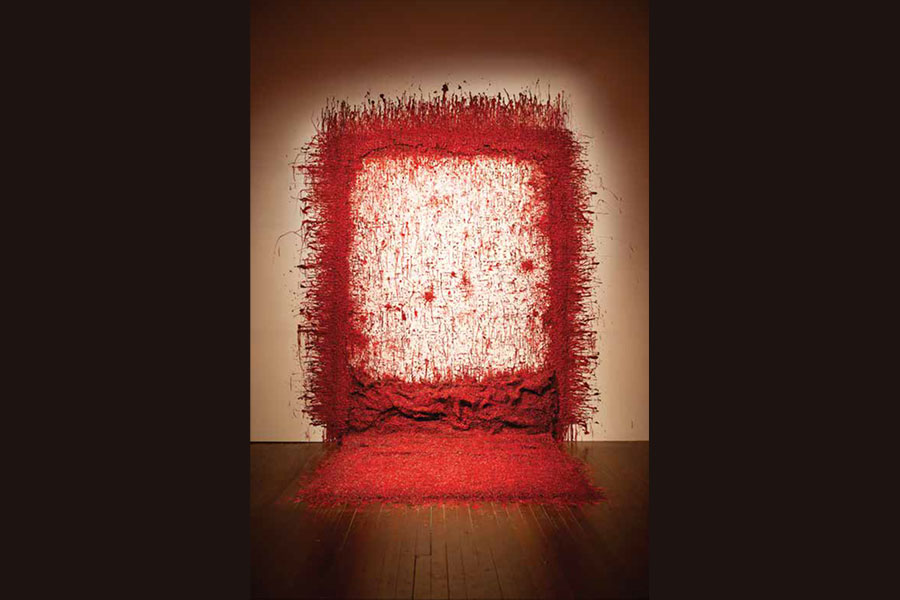

From the 1960s onwards, Singapore saw the emergence of major artists in various genres such as ceramics, sculpture, painting, print-making and performance art, many of whom have been awarded the Cultural Medallion—the nation's highest distinction for artists and cultural professionals.

A distinct break occurred in the late 1980s with the radical and controversial The Artists' Village (TAV) - an artist colony, collective and movement established by contemporary artist Tang Da Wu, which counted amongst its ranks ground-breaking artists such as Amanda Heng, Chng Seok Tin and the late Lee Wen. TAV, still active today, derives its notoriety from a ban on performance art in Singapore following a performance by artist Josef Ng in 1994 which saw him snipping his pubic hair in public. TAV’s complex multi-faceted work defied categorisation and would prefigure today's new generation of local installation and multi-media artists.

In the meantime, the 1990s and 2000s saw significant investment by the government into the arts and culture scene, with the aim of turning around the perception of Singapore as a "cultural desert" and re-positioning Singapore as a "Renaissance City". The investment in the arts has borne fruit in terms of an extremely vibrant and active arts and heritage scene, with young Singaporean artists gaining prominence on the international stage.

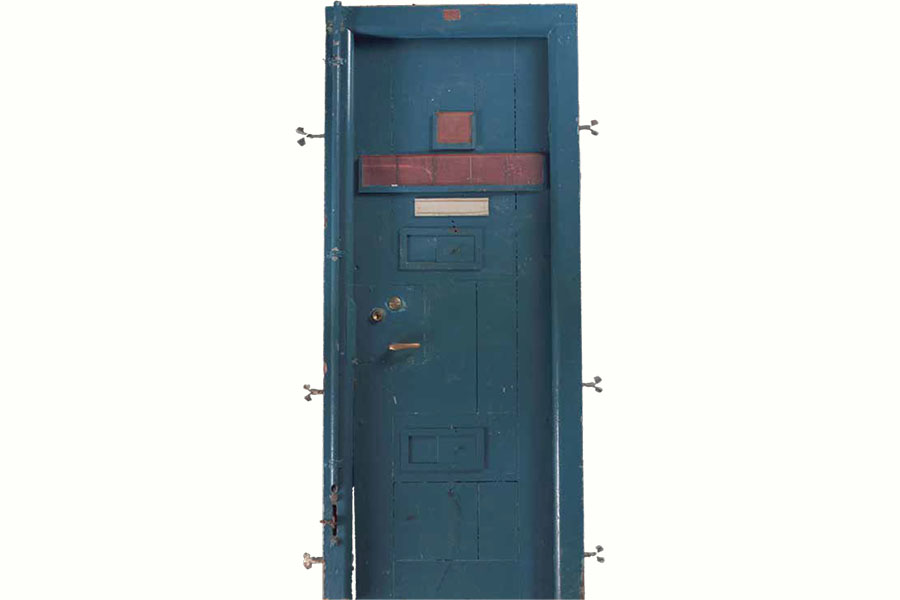

E) Self-Government and Independence

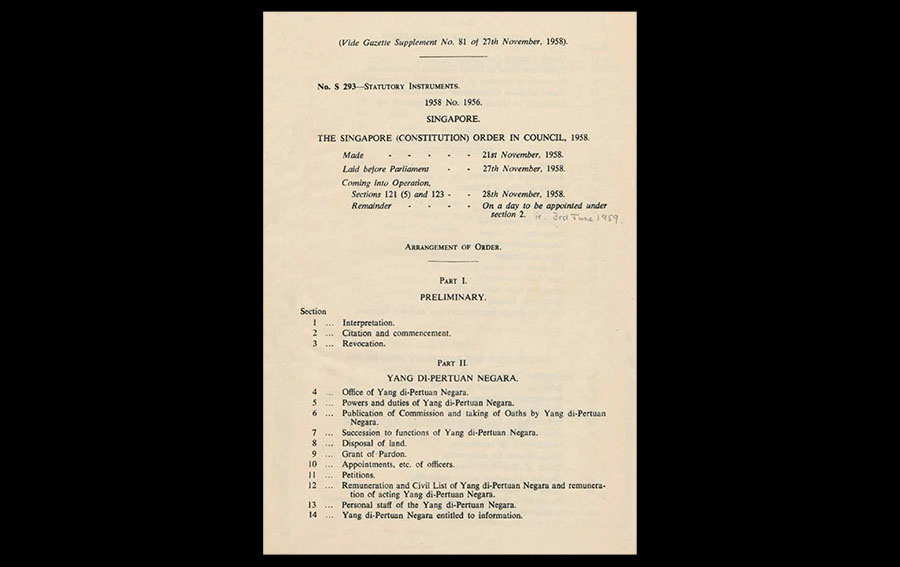

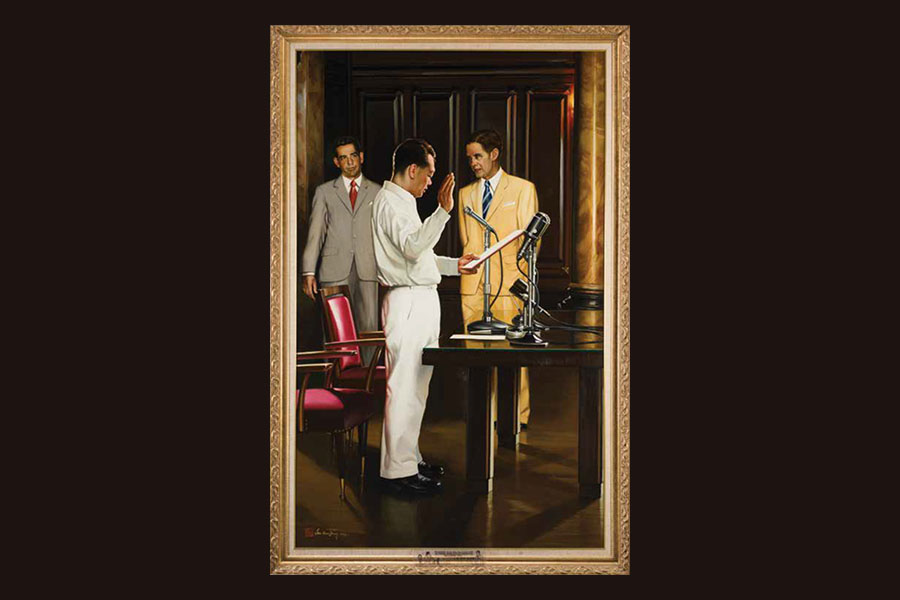

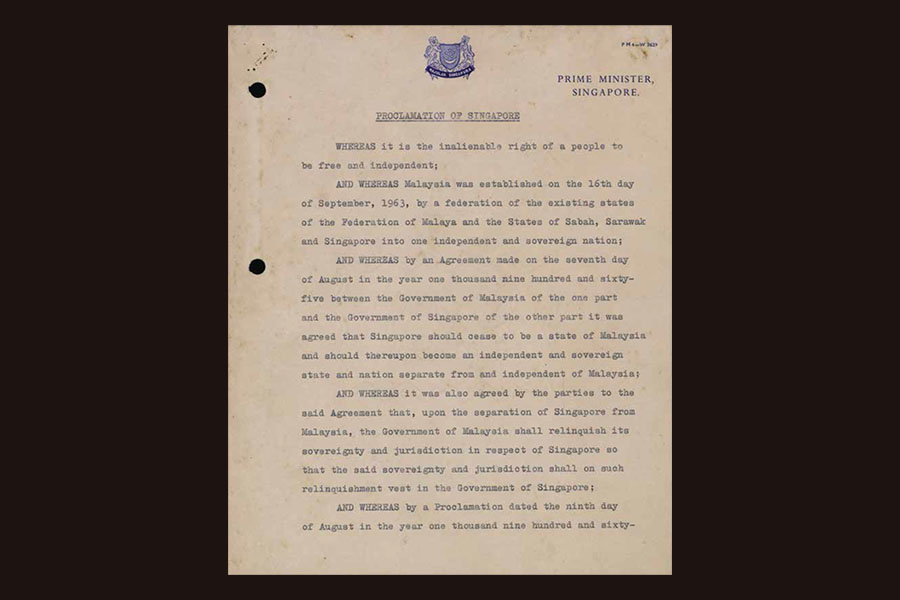

The State of Singapore Constitution of 21 November 1958 articulated the structure of government for a self-governing Singapore, with the post of governor replaced by the office of the Yang di-Pertuan Negara, and with a fully-elected Legislative Assembly. Self-government was actualised on 5 June 1959, with the late Lee Kuan Yew sworn in as Singapore's first Prime Minister, alongside his first cabinet. To mark this significant milestone, a new national flag and anthem were adopted.

In 1963, Singapore ceased being a colony of Great Britain by merging with Malaya, Sarawak and Sabah to form the Federation of Malaysia. Barely two years later, Singapore would leave the federation, with the Proclamation of the Republic of Singapore on 9 August 1965 declaring Singapore its own independent republic.

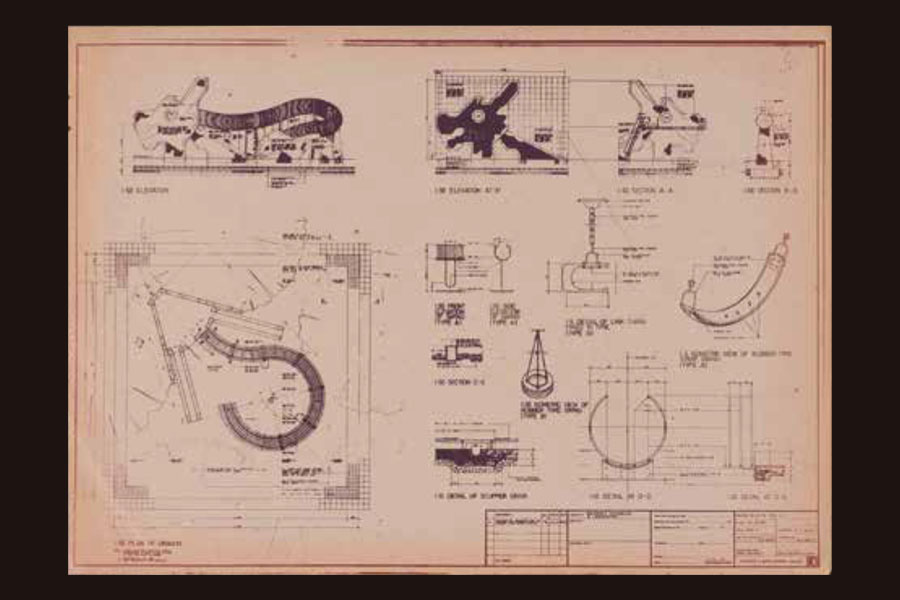

Singapore's post-independence years saw significant economic growth grounded in a burgeoning manufacturing and electronics sector. Heritage brands such as Tiger Balm and Singapore's blossoming into the "Garden City" of Asia contributed to a more vibrant lifestyle and tourism scene.

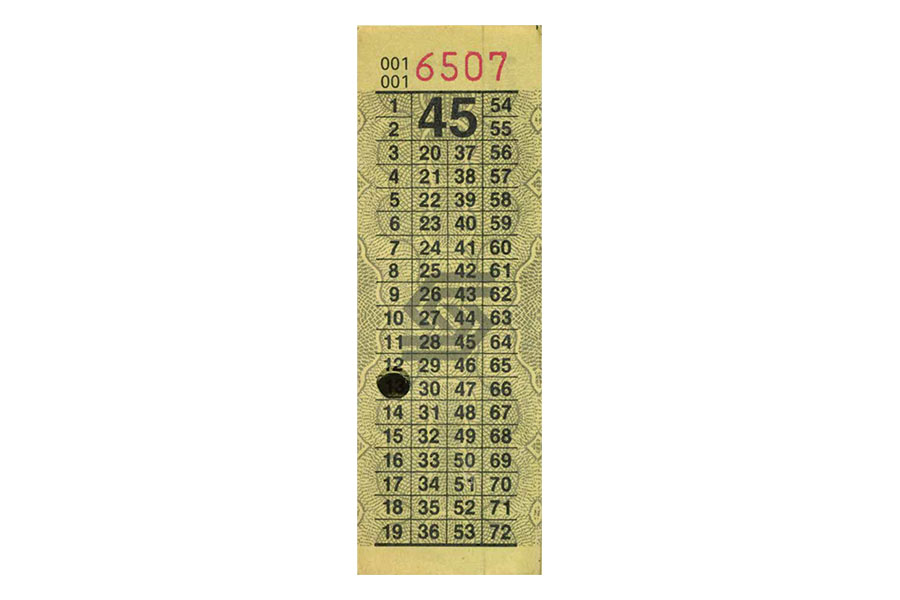

In the 1980s, economic growth was accompanied by advances in the socio-cultural space, with Singapore investing in what continues to be one of the most extensive and radical public housing programmes in the world. The inclusion of a humble bus ticket from this period as the final object in the graphic spread makes a poignant statement on the great strides post-independence Singapore has made, from being a post-colonial, developing nation to today's global, first-world metropolis.

Singapore in the 1990s and 2000s continued to sustain its growth and build on its global positioning through espousing free trade and continually diversifying its economy while enhancing its urban, social and environmental landscape and infrastructure. It is considered one of the most dynamic and liveable cities in the world today.

Acknowledgements

The main and section text is written by the author while objects selected and the accompanying captions are edited by the author, based on recommendations and curatorial captions contributed by curators, archivists and other colleagues at Asian Civilisations Museum and Peranakan Museum, Asian Film Archive, Indian Heritage Centre, Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National Archives of Singapore, National Gallery Singapore, National Heritage Board, National Library Singapore, National Museum of Singapore, Singapore Art Museum and Singapore Botanic Gardens. See acknowledgements for full list of contributors.

The author would like to thank colleagues at the following institutions, who have advised on objects for this spread, contributed curatorial content, or supported the project in one way or another.

Asian Civilisations Museum and Peranakan Museum

- Theresa McCullough, Principal Curator

- Clement Onn, Senior Curator / Asian Export Art and Peranakan

- Dr Stephen Murphy, Senior Curator / Southeast Asia

- Noorashikin Zulkifli, Curator / West Asia

- Naomi Wang, Assistant Curator / Southeast Asia

Asian Film Archive

- Karen Chan, Executive Director

- Chew Tee Pao, Archivist

- Janice Chen, Archive Officer

Indian Heritage Centre

- Nalina Gopal, Curator

Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum

- Prof Ng Kee Lin, Peter, Head

- Low Ern Yee, Martyn, Research Associate

National Gallery Singapore

- Dr Eugene Tan, Director

- Lisa Horikawa, Deputy Director / Collection Development

- Renee Stahl, Manager / Information

National Archives of Singapore

- Wendy Ang, Director

- Kevin Khoo, Specialist / Oral History Centre

National Library Singapore

- Tan Huism, Acting Director

- Gladys Low, Manager / Content and Services

National Museum of Singapore

- Angelita Teo, Director

- Iskander Mydin, Curatorial Fellow

- Priscilla Chua, Curator

Singapore Art Museum

- Dr June Yap, Director of Curatorial, Programmes and Publications

Singapore Botanic Gardens

- Dr Nigel Taylor, Group Director

- Terri Oh, Director of Education

- Christina Soh, Manager / Library

Notes

According to the Pew Research Center’s demographic study in 2014.

1.

https://www.pewforum.org/2014/04/04/global-religious-diversity/

Bibliography

Asian Civilisations Museum. 2017. ACM Treasures – Collection Highlights. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum.

Dozier, Laura, ed. 2010. Natural History Drawings - the Complete William Farquhar Collection - Malay Peninsula 1803-1818.

Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore.

Ho, Stephanie. 2013. “Cheongsam.” In Singapore Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2013-09-27_171732.html .

Koh, Jaime. 2013. “Chettiars.” In Singapore Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2013-12-11_165654.html.

—. 2013. “Sikh Community.” In Singapore Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2013-07-29_174120.html

Lim, Irene. 2016. “Haw Par Villa (Tiger Balm Gardens).” In Singapore Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_560_2004-12-14.html.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2013-07-29_174120.html, Siew Yeen, and Mazelan bin Anuar. 2013. “National Courtesy Campaign.” In Singapore Infopedia. Singapore: National Library Board. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_162_2004-12-30.html?s=courtesy.

Low, Sze Wee. 2015. Between Declarations and Dreams: Art of Southeast Asia Since the 19th Century.Singapore: National Gallery Singapore.

Murphy, Stephen A., Naomi Wang, and Alexandra Green, eds. 2019. Raffles in Southeast Asia – Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum.

National Heritage Board. 2016. “Changi Prison Gate Wall and Turrets.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://roots.sg/Content/Places/national-monuments/changi-prison-gate-wall-and-turrets.

—. 2016. “Chesed-El Synagogue.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://roots.sg/Content/Places/national-monuments/chesed-el-synagogue.

—. 2016. “Former Tanglin Halt Industrial Estate.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://roots.sg/Content/Places/landmarks/my-queenstown-heritage-trail/former-tanglin-halt-industrial-estate.

—. 2016. “National Flag.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://www.nhb.gov.sg/what-we-do/our-work/community-engagement/education/resources/national-symbols/national-flag.

—. 2016. “Shirin Fozdar.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://roots.sg/learn/stories/shirin-fozdar/story.

—. 2016. “Toa Payoh Dragon Playground.” In Roots.Sg. Singapore: National Heritage Board. https://roots.sg/Content/Places/landmarks/toa-payoh-trail/toa-payoh-dragon-playground.

National Library Board. 2014. “1958 State of Singapore Constitution Is Adopted, 3rd June 1959.” In HistorySG. Singapore: National Library Board. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/be12893b-2734-4297-b6df-c7229bb05259.

Storer, Russell, Clarissa Chikiamco, and Syed Muhammad Hafiz, eds. 2018. Between Worlds: Raden Saleh and Juan Luna.Singapore: National Gallery Singapore.

Tan, Szan, and Hwei Lian Wong. 2006. The Xiang Xue Zhuang Collection: Donations to the Asian Civilisations Museum.Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum.

Ting, Kennie. 2019. Singapore 1819 – A Living Legacy. Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd.

Wright, Nadia H., Linda Locke, and Harold Johnson. 2018. “Blooming Lies – The Vanda Miss Joaquim Story.” Biblioasia 14 (1).

The object captions in this graphic spread consist of existing curatorial content that has been minimally edited for length by the author. This content was researched and written by curators, archivists and subject specialists at the institutions featured in this spread at various times in the history of these institutions.The content has been, in most cases, adapted from curatorial content directly provided by the institutions, existing content in collection databases, display captions in the institutions’ galleries, as well as the following publications and online references created and maintained by the featured institutions.