Text by Tan Huism, Deputy Director, Content and Services (Singapore, Southeast Asia and Exhibitions), National Library

MuseSG Volume 10 Issue 2 - 2017

"One day a clerk named Ibrahim came to my house and mentioned in conversation that Mr Raffles was looking for Malay clerks with a good hand, and he wanted to buy Malay documents and romances of olden times."

– Hikayat Abdullah, 1849. Translated by Ian Proudfoot.

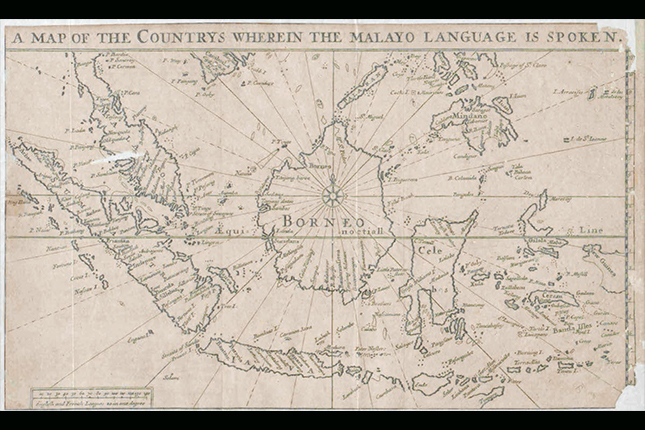

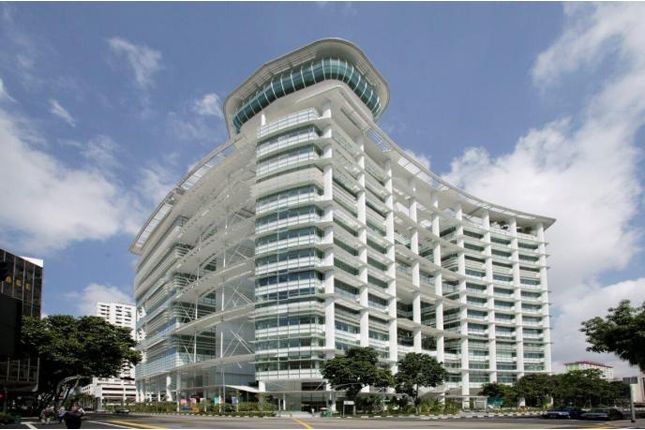

In some of the European libraries today, you will find Malay manuscripts which were brought there by scholars, missionaries and administrators from colonial times. In the National Library’s exhibition, Tales of the Malay World: Manuscripts and Early Books, visitors had the opportunity to view rare books from the holdings of three important European institutions: the British Library; the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; and Leiden University Library from 18 August 2017 to 25 February 2018. For the first time, many of these manuscripts were returned to the region in which they were originally written. Together with the National Library’s Rare Materials Collection, these artefacts told fascinating stories of the societies that wrote and read them.

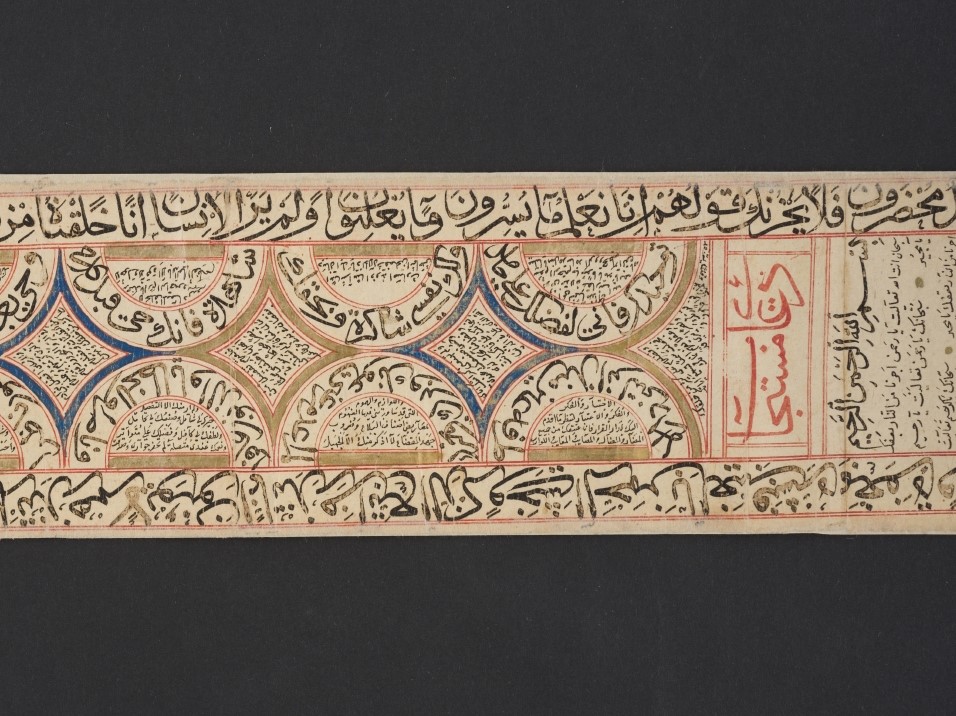

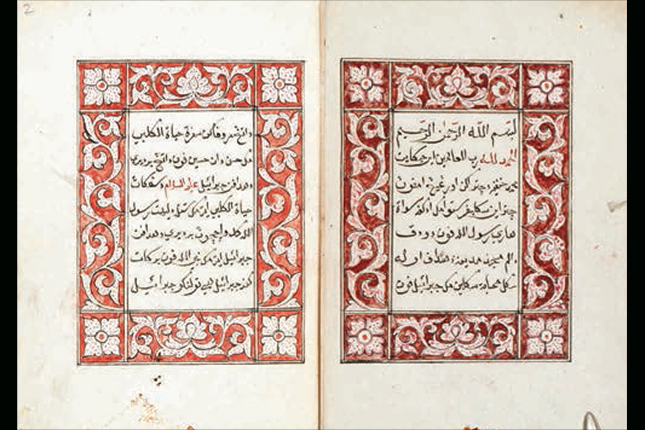

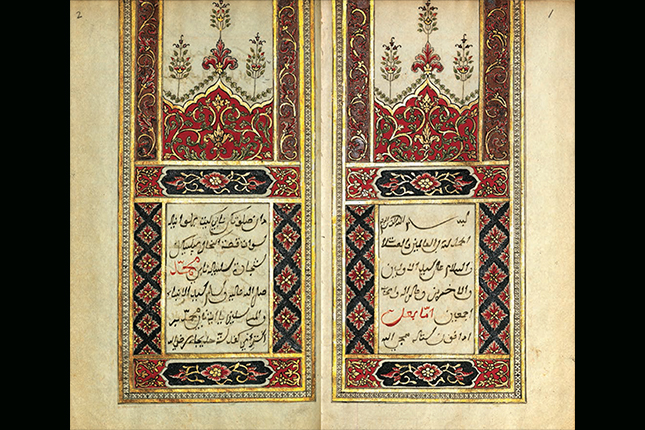

While people today tend to perceive reading as primarily a visual act, written Malay works were traditionally experienced orally and aurally. The reading of manuscripts aloud to an audience is mentioned in various old Malay manuscripts. A well-known episode in the Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings) relates how the nobles of Melaka requested for the Hikayat Muhammad Hana ah to be read to them on the eve of their battle with the invading Portuguese. Intended to spur valour, the hikayat (narrative tale) relates the romanticised exploits of the Islamic warrior Muhammad Hana ah, half-brother of Prophet Muhammad’s grandsons. To emphasise the oral-aural experience of Malay manuscripts, this exhibition featured a recitation of this episode from the Sulalat al-Salatin, as well as the singing of two works of syair (poetry).

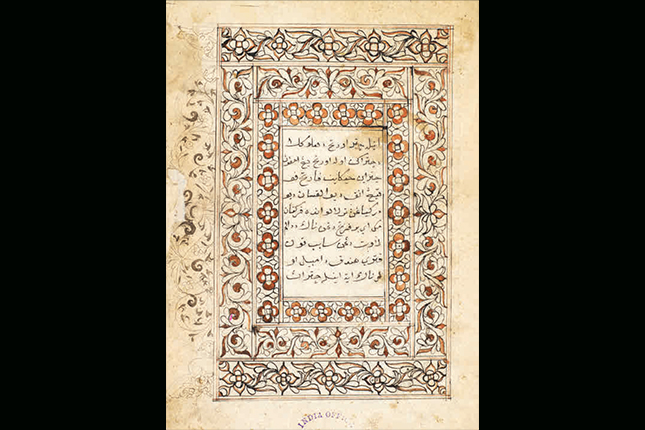

Collection of the British Library, MSS Malay B.6.

World of Malay Literary Manuscripts

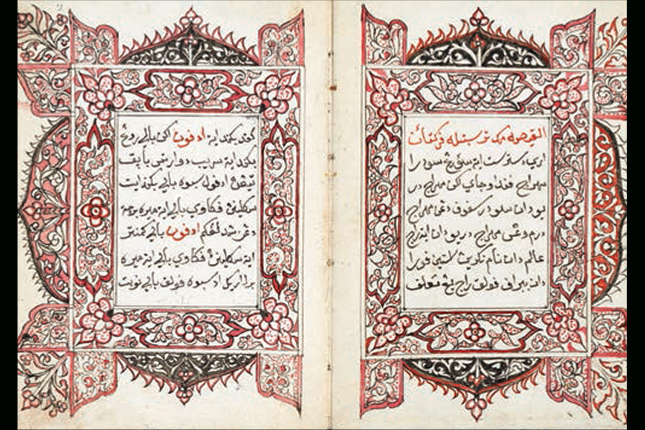

Our understanding of traditional Malay written literature depends largely on what has survived. Except for a few written in southern Sumatran scripts, almost all extant Malay manuscripts are written in Jawi (modified Arabic script). Islam played a prominent role in the development of the Malay written literary tradition. The earliest literary works are believed to have been created in the 14th century, after the arrival of Islam in the region, and they even include stories with Hindu-Buddhist influences like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

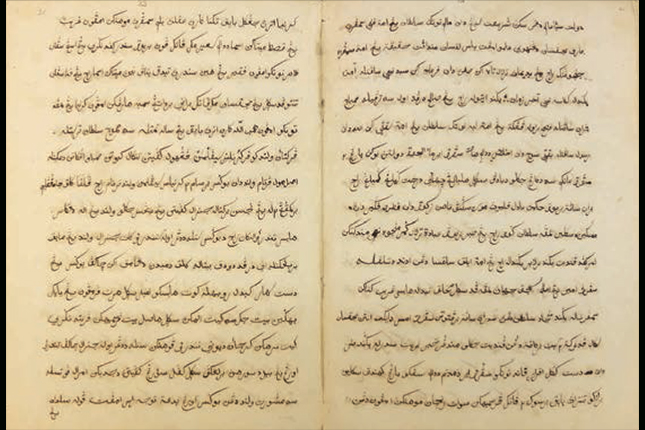

Collection of the British Library, MSS Malay B 12.

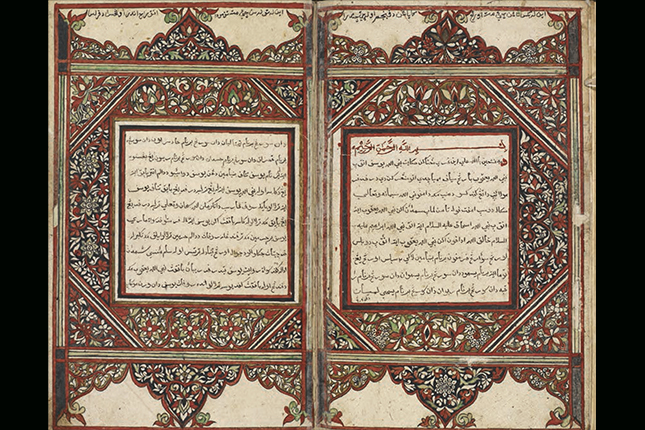

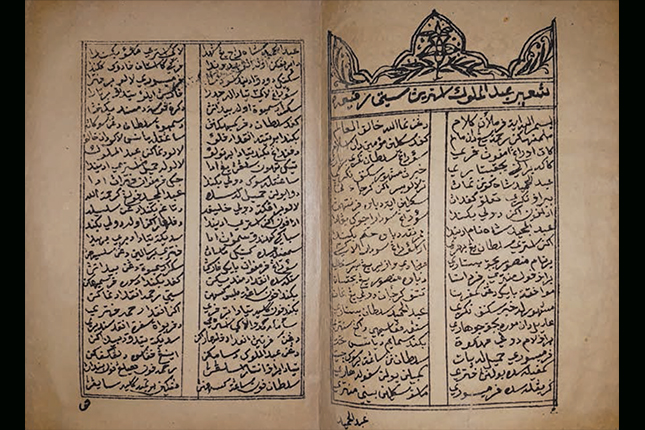

This exhibition introduced visitors to various kinds of literary works such as court chronicles that trace the genealogy of ruling families (image 03), romantic and historical poetry (image 04), fantastical adventure stories and Su tales (image 05). Generally, the terms referring to these literary works include salasilah (genealogy), hikayat and syair.

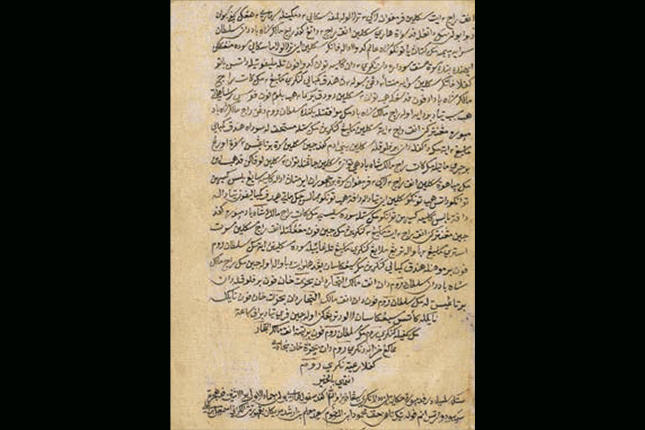

Collection of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Raffles Malay 30.

Collection of the Leiden University Library, Cod. Or 1626.

Collection of the National Library of Singapore, B16283380I.

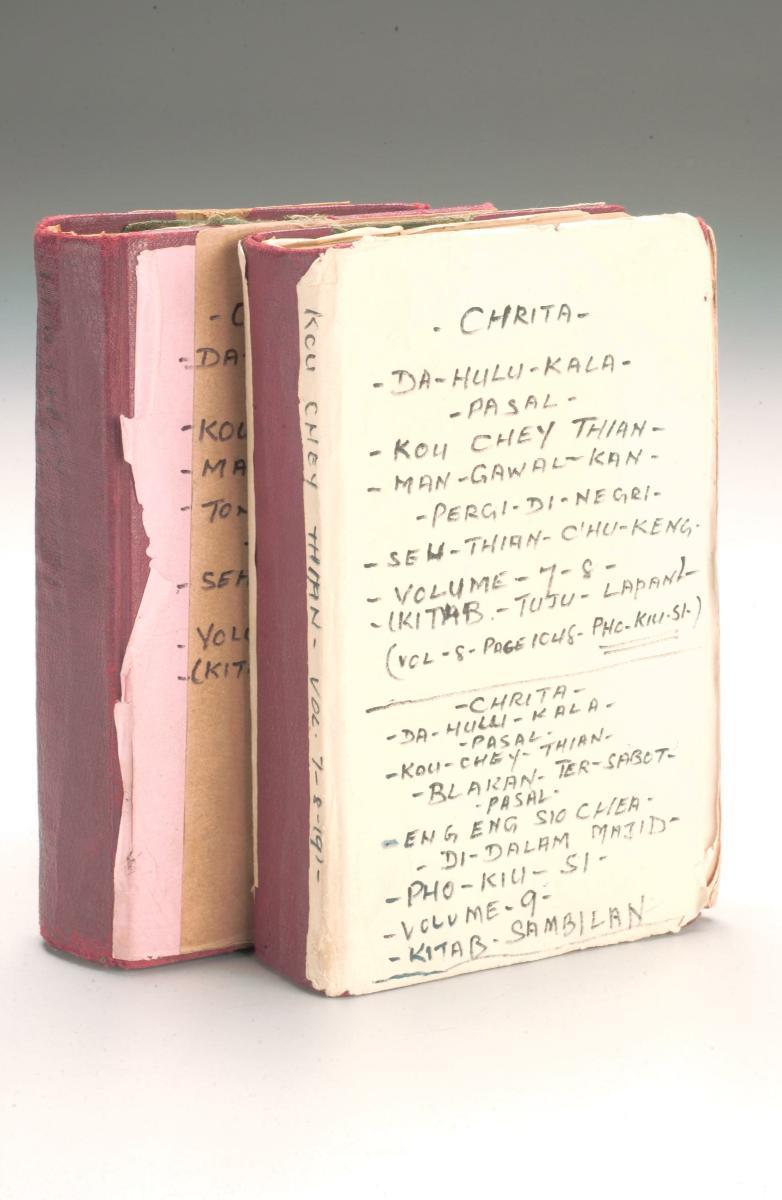

The majority of these works are anonymous and undated, which makes it difficult for scholars to trace the development of Malay traditional literature. Those that contain additional information provide rare glimpses into the production of manuscripts and their readers. For example, the only known manuscript that contains an inscription of the artist’s name – Cik Mat (Muhammad) Tuk Muda, son of Raja Indera Wangsa, from Kayangan, Perlis – also has a note in which the owner Cik Candra implores readers to take good care of the manuscript. Lending libraries were established in various urban centres in the 19th century. This exhibition featured a few examples of such manuscripts for loan, such as the popular Hikayat Cekel Waneng Pati, a Panji tale copied by Muhammad Bakir, whose family ran a lending library in Batavia (Jakarta) from the mid to late 19th century.

Collection of The British Library, MSS Malay D 4.

Market for Manuscripts

Traditionally, access to manuscripts was limited, as they were held at the courts by feudal chiefs or storytellers. Scholars have mostly credited Stamford Raffles (1781- 1826) for creating a public market for Malay written texts. He started buying manuscripts in a way similar to how he collected natural history specimens, and even hired a team of six scribes to copy texts that he had borrowed. In this exhibition, there is a hikayat that was copied by one of Raffles’ scribes, Ibrahim Kandu, a Chulia who lived on the Prince of Wales Island (Penang). The British were not the only Europeans actively collecting; the Dutch were also collecting in earnest. European administrators and scholars collected Malay manuscripts to learn the language and understand the culture, so as to better administer the region or to fulfill missionary purposes.

From Written to Printed

The adoption of the lithographic press by Malay/Muslim printers from the mid-19th century onwards had a dramatic effect on the manuscript tradition. Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (c. 1797-1854), better known as Munshi Abdullah, is considered a pioneer of Malay printing. He had learnt printing from the English missionary, Walter Medhurst (1796-1857) while in Melaka, and was involved in various mission publications as either translator or editor. Abdullah even composed new works to be printed, becoming the first non-European to have his work printed in Malay.

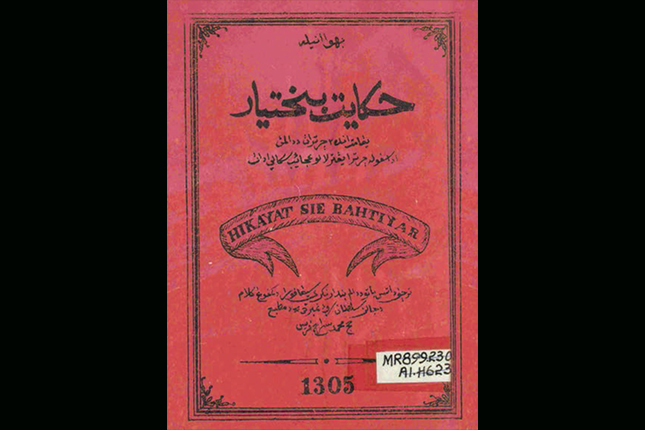

From the mid-19th century, Singapore, or more specifically Kampong Gelam, grew to become an important printing hub for Malay/Islamic books that were distributed throughout the Malay world. Lithography basically reproduced the manuscript format, but enabled multiple copies to be produced economically. Like their manuscript counterparts, these early mass-produced printed hikayat and syair were also recited or sung for an audience. However, one important difference is that these printed texts were now widely available for sale. By the turn of the 20th century, however, Singapore printers had begun to decline as the local and regional markets saw an influx of Malay books from Bombay, Cairo, Mecca and Istanbul. In this exhibition, visitors discovered prominent printers, their marketing tactics, and their bestselling titles.

Collection of National Library of Singapore, B03013464J.

Collection of National Library of Singapore, B29362100A.

Enduring Stories

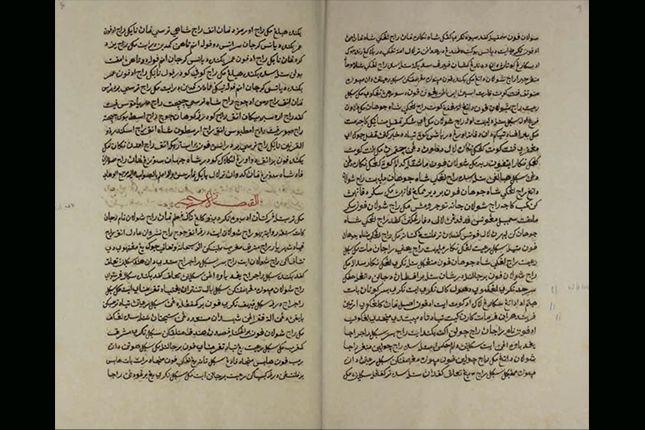

While many of us in Singapore may not be familiar with traditional Malay literature, there are some stories that have endured through the centuries. This exhibition explored three such literary works: Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings; popularly known as the Sejarah Melayu), Hikayat Hang Tuah (Tale of Hang Tuah) and Hikayat Pelanduk Jenaka (Tale of the Wily Mousedeer). All three works have been adapted as novels, comics, plays or films. Of interest to Singaporeans will be the Sulalat al-Salatin, which contains a legend about early Singapore and how it got its name. The popular tale about the attack of the garfish can also be found in the Sulalat al- Salatin. Visitors were able to view the earliest manuscripts of Sulalat al-Salatin (known to scholars as “Raffles 18”) and the Hikayat Hang Tuah in physical form, as well as through a retelling on the silver screen.

Collection of Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Raffles M18.