TL;DR

Pantun is a traditional Malay poetic form that, through gentle advice and metaphors drawn from nature, serves as a vehicle for expressing universal values, fostering multicultural harmony, and sharing wisdom across generations. While its usage has declined, efforts are ongoing to preserve and revitalise this art form beyond its technical aspects to highlight its deeper philosophical and social significance.

Pantun is a branch of traditional poetry in Malay culture that has long captivated the interest and imagination of scholars and observers worldwide. Its authenticity and unique structure provide a window to explore the life, thoughts, and aesthetic philosophy of the Malay people in the past. Compared to other traditional forms of poetry, pantun is the finest example of wisdom, a mode of expression, and a way of communication for the Malay community. Primarily, pantun is an oral literary genre, only beginning to be documented with the advent of printing technology in the region. This development further accelerated its usage, teaching, learning, and research.

In modern-day Singapore, pantun continues to be part of local culture, even though the society is metropolitan and modern. Numerous initiatives elevate pantun in classrooms and events, such as pantun competitions, inauguration ceremonies, and weddings. Aside from its form, rhyme, and rhythm, the lasting appeal and relevance of pantun lie in two key aspects: 1. Its biophilic nature, and 2. It’s embracing spirit. This essay will delve into these aspects further.

The Biophilic Pantun

The beauty of pantun lies in its lively, life-giving nature. The Western thinker Erich Fromm refers to this quality as biophilia, describing it as “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive[1]” and the hope for “further growth, whether in a person, a plant, an idea, or a social group[2]”. Pantun serves as a guiding light, expressing universal human values such as virtue, honesty, and love, countering moral decay like greed, arrogance, and hatred.

There are various such interpretations within traditional pantun, ranging from short two-line couplets to more elaborate multi-line verses. For example, our ancestors have long composed about the importance of knowledge:

Buah jambu dimakan kera,

Dipetik Rukiah lari ke hutan;

Ilmu itu bertiang tiga,

Dialah cahaya penyuluh jalan.[3]

Translation:

The guava fruit is eaten by monkeys,

Plucked by Rukiah, running to the woods;

Knowledge stands on three pillars,

It is the light that illuminates the path.

This means that a person can elevate themselves from the depths of ignorance that entrap and bind them by seeking knowledge. The pursuit of knowledge is not confined to formal schooling, as is often the case today. It challenges the fatalistic mindset often associated with the Malay community. Instead, the search for knowledge requires active effort, only through which true freedom in life can be achieved:

Malam ini malam Isnin,

Malam besok malam Selasa;

Tuntutlah ilmu sampai berkenan,

Lepaslah kamu dari seksa.[4]

Translation:

Tonight is Monday night,

Tomorrow will be Tuesday night;

Seek knowledge to your heart’s content,

And free yourself from torment.

Next, an element often brought to life in pantun verses is the element of advice. Advice serves as a teaching, invitation, and guidance towards all that is good. Just as a mother treats her child—with gentleness, affection, and compassion—so too does the pantun, embodying the same tenderness, warmth, and kindness. This is important because pantun can also emerge as a form of social critique. However, it is rare, if not impossible, for a pantun to aim towards any form of evil or destructive negativity. It does not extinguish the spirit to improve oneself and one’s circumstances. Advice blended with courtesy, without fiery emotional outbursts—this is the nature of the Malay pantun, which has become a cherished part of our literary heritage:

Menahan pukat ke seberang,

Dapat seekor ikan tenggiri;

Jangan cakap sebarang-sebarang,

Kelak memakan diri sendiri.[5]

Translation:

Casting the net across,

Catching a single mackerel fish;

Do not speak recklessly,

Lest it comes back to harm you.

Once upon a time, pantun thrived during the era of Malay feudalism, a time when the sultans and the nobility were often cruel. Oppressive, exploitative, and repressive conditions for the common people were the norm. Naturally, the rakyat (people) of that time lacked the means or ability to escape the shackles and restrictions imposed upon them. Any attempt to resist power was met with curses and punishment. Yet, it is rare to find a pantun that speaks of despair, even in the face of hopelessness. Instead, patience emerged as one of the enduring expressions in enduring life’s struggles. It became advice that was neither reckless nor indifferent but considerate of the realities of its society. This is the pantun that continues to live and breathe life:

Apa guna pokok kiambang,

Sehari-hari gugur daunnya;

Apa guna menaruh bimbang,

Menahan sabar banyak gunanya.[6]

Translation:

What is the use of the water hyacinth,

Whose leaves fall day by day;

What is the use of harbouring worry,

Patience brings many rewards your way.

The Embracing Pantun

Beyond its vibrant nature, the beauty of the pantun lies in its embracing spirit. “Embracing” here refers to its support for principles and practices that are just for all, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, religion, or socioeconomic status. It aims towards unity and social justice, fostering a spirit of egalitarianism and democratic ethos. This is one of the reasons why themes of love, affection, and care are central to traditional pantun verses. Without these sentiments, it would be impossible for one to embrace something greater than oneself: “the main condition for the achievement of love is the overcoming of one’s narcissism.”[7] The embracing pantun manifests love for: (1) humanity and society, and (2) nature.

Love Cinta Towards Humanity and Society

It is well-known that pantun has become an integral part of the socio-cultural fabric of the Malay community. A more comprehensive study could be undertaken if it considers “notions of all sorts of human activities, way of life, social relations, ceremonies etc.”[8] This is because pantun serves as a vessel for the outpouring of love and affection for humanity without discrimination. The portrayal of humanity in pantun is not confined to the Malay people alone. It uplifts the humanity of every individual, transcending regional, local, and ethno-cultural boundaries. For example, traditional pantun often includes positive references to ‘anak Cina’ (Chinese children) and ‘anak India’ (Indian children), reflecting how pantun has long borne witness to the harmonious multicultural coexistence within society. No derogatory or chauvinistic language is found, unlike the divisive rhetoric increasingly prevalent today. Instead, these pantuns are accompanied by values of courtesy and good conduct:

Anak Cina mengirim surat,

Dari Jawa sampai ke Deli;

Hidup kita dikandung adat,

Budi tidak dijual beli.[9]

Anak India membawa madat,

Dari Kedah langsung ke Bali;

Hidup manusia biar beradat,

Bahasa tidak berjual-beli.[10]

A Chinese child sends a letter,

From Java to Deli;

Customs and culture shape our lives,

Virtue cannot be bought or sold.

An Indian child brings opium,

From Kedah straight to Bali;

A human’s life honours tradition,

Virtue cannot be bought or sold.

In addition, the contributions of farmers are often mentioned, particularly their methods of planting and tending to rice. Rice, as the staple food for most people in the Nusantara, is regarded as a symbol of dedication and service. Thus, it is not surprising that it reappears as a correlative to expressions of love and virtue:

Orang Acheh menanam padi,

Padi tumbuh nampak jarang;

Antara kasih dengan budi,

Budi juga dikenang orang.[11]

Orang berhenti tepi surau,

Lihat padi campur Jerami;

Tujuh tahun musim kemarau,

Baharulah sedar rumput di bumi.[12]

The Acehnese plant the rice,

The rice grows sparse in sight;

Between love and virtues,

Virtue is what people hold tight.

People pause by the surau,

Seeing rice mixed with straw;

Seven years of drought,

Only then they see the grass nearby.

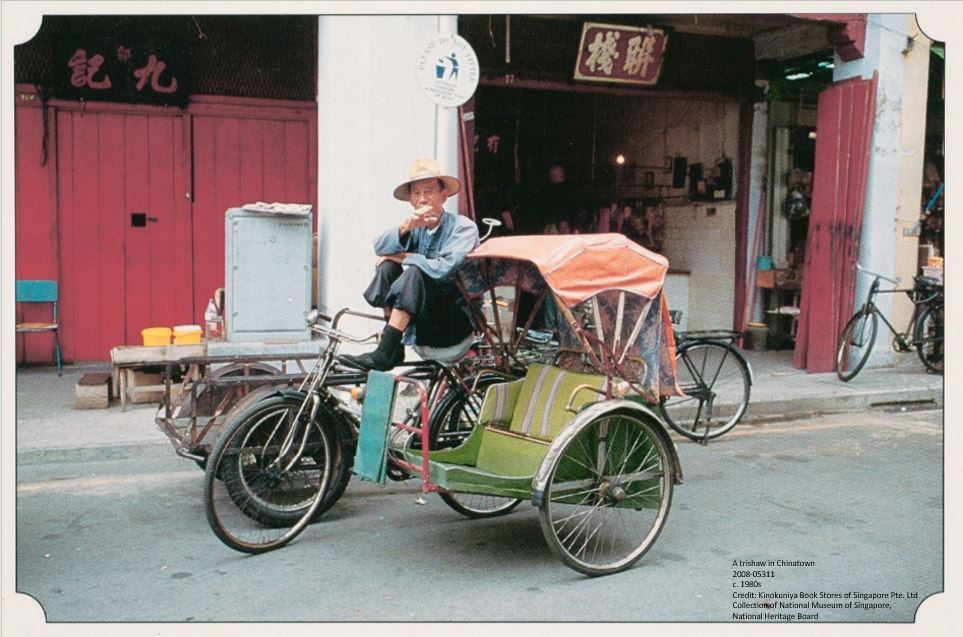

Love for Nature

Another aspect often explored in pantun is the recognition of nature. Understanding nature helps foster a sense of connection and relationship between humans and the world around them. It serves as a reminder that humans are part of a larger ecosystem. Knowledge of nature in pantun encompasses flora and fauna, aquatic life, animals, and similar elements. This reflects the harmonious relationship between the Malay community and nature. Without observation and reflection on the surroundings, it would be impossible to share such feelings in pantun. Today, reading pantun offers a gateway to a world often overlooked, especially amidst the hustle and bustle of urban life. The environmental crises of today call for care and concern for nature as a manifesto of love that must be nurtured and revived. Although nature is often used as a metaphor or preambles in pantun, its use highlights what once captured the Malay community’s attention and led to larger themes of goodness. This is because nature precedes and frames human life. Examples of such traditional pantun include:

Siakap sinohong, gelama ikan berduri,

Bercakap bohong, lama-lama mencuri.[13]

A silver barramundi, a thorny jewfish,

Telling lies may lead to theft over time.

Sudah gaharu, cendana pula,

Sudah tahu, bertanya pula.[13]

If it’s agarwood, why mention sandalwood,

If you already know, why ask again.

The Search for Relevance and Hope

There is no doubt that pantun is a highly valuable treasure of folk literature. It was widely used in the past, serving not only as a vessel for life’s philosophies but also as a reflection of the intellectualism of the Malay community in expressing their resolve and thoughts. In recent times, pantun has been less commonly utilised than it was in the days of our ancestors. However, this should not cause alarm but rather inspire planning and initiatives to present pantun more sincerely and meaningfully. Efforts to preserve pantun have already been initiated, such as incorporating it into teaching and learning in schools. Unfortunately, these efforts remain limited to technical and aesthetic aspects. While commendable, they do not fully capture the holistic beauty embedded in pantun’s verses. There must also be attempts to reveal its biophilic nature and embracing spirit so that pantun resonates more deeply with contemporary audiences. It would be even more impactful if pantun were elevated as a beacon of wisdom that advocates for life, social justice, unity, and egalitarianism. We should not simply excel in crafting and reciting pantun without shouldering the moral and ethical responsibility towards society and the environment. Rightfully, pantun should become an art of shared emotions and reciprocal courtesy.

About the Author

Muhammad Iylia Kamsani is a dikir barat practitioner and literature enthusiast pursuing a Master’s in Malay Studies at the National University of Singapore (NUS). Appointed as a Sahabat Sastera (Friend of Malay Literature) by the Malay Language Council, Singapore (Majlis Bahasa Melayu Singapura or MBMS) in 2021, Iylia has gained various opportunities to explore literature locally and abroad. He has presented at local language and literary programmes and represented MBMS and Singapore at regional forums and seminars under the Southeast Asian Literary Council (Mastera).

Originally written in Malay by Muhammad Iylia Kamsani, this essay was first published in Berita Harian. The Malay Heritage Centre commissioned it to accompany its Intangible Cultural Heritage Conversation Video Series.

This video, produced by the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC), is part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage conversation series, celebrating the exceptional talents that contribute to shaping our cultural landscape. The interview with Encik Afi Hanafi, a passionate artist and advocate for syair, delves into the beauty of traditional Malay music and poetry. As the founder of Orkestra Sri Temasek, Permaisuara, and Syairpura, he shares his journey of preserving and promoting syair through captivating performances and community engagement.

Notes

- Erich Fromm, The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, (New York: Fawcett Crest, 1973), 406.

- Ibid.

- Kurik Kundi Merah Saga. See the link: http://prpmv1.dbp.gov.my/Default.aspx.

- Ibid.

- Muhammad Haji Salleh, Romance and Laughter in the Archipelago: Essays on the Contemporary Poetics of the Malay World, (Pulai Pinang: Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia), 41.

- Ibid.

- Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving, (New York: Harper and Row, 1956), 118.

- Francois-Rene Daillie, Alam Pantun Melayu: Studies on the Malay Pantun, (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1990), 131.

- See Muhammad Haji Salleh, Romance and Laughter, 36.

- See Kurik Kundi Merah Saga: http://prpmv1.dbp.gov.my/Default.aspx.

- Ibid.

- Muhammad Haji Salleh, Romance and Laughter, 11.

- Ibid.