TL;DR

Dr Ivan Polunin—documentarian, field doctor, ethnographer—wore many hats, and left behind a body of work that defies easy categorisation. His photographs from 1950-1980 transcended historical documentation, capturing Singapore during a transformative period—from intimate glimpses of daily life to the sweeping tide of rapid urbanisation. Once Upon an Island, published in 2023 by Suntree Media with NHB’s support, not only showcases his work, but also chronicles the challenge of shaping a vast, personal archive into a meaningful publication decades later. This article follows Asmara Rabier—Polunin’s granddaughter and the book’s lead editor—as she pieces together his collection, discovering him not just as the kind figure she knew, but as an explorer, academic, and relentless documentarian.The Life and Work of Dr Polunin

Dr Ivan Polunin was an eclectic figure. Born in 1920 in Middlesex, London, he arrived in Singapore as a junior doctor under the Colonial Office and spent much of his career working across Malaya.[1] What began as medical fieldwork gradually evolved into a broader ethnographic and photographic practice. From the 1950s to the 1980s, he documented various communities and landscapes he encountered during his travels.

Photography was central to Polunin’s practice, but its role shifted over time. He first used it in a clinical context—documenting diseases among indigenous groups during his medical practice.[2] But the camera soon became more than a research tool. In 1951, he began filming for personal interest, using a Revere Double Run 8mm camera to capture Malay fishermen sailing in traditional perahu from Siglap during the northeast monsoon.[3] This quiet curiosity about everyday life in all its forms would become the defining characteristic of his work.

Over the decades, he amassed an extraordinary archive: more than 40,000 colour slides, reels of 16mm film, and thousands of photographs.[4] In his later years, Polunin became deeply invested in preserving this material—cleaning, restoring, and collaborating with the National Archives of Singapore.[5] He also began drafting a manuscript he hoped would become a book of stills drawn from his colour films. He called it Das Buch—“The Book” in German.[6]

When Dr Ivan Polunin passed away in 2010, his magnum opus Das Buch remained unfinished.[7] The work had almost been published through a collaboration with academic Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan, but Pulonin’s relentless perfectionism and the sheer scale of the archive made it difficult to bring to completion. “It was never good enough,” his granddaughter Asmara Rabier recalls.[8] Eventually, the project stalled—leaving behind boxes of handwritten and typewritten notes, fragments of a manuscript, and decades of images gathering dust in the basement.[9]

Years later, a chance meeting between Dr Tan and Asmara’s mother reopened the door. The archive was still intact, waiting. For Asmara—who had grown up around the material without ever truly engaging with it—this was the moment. What began as a vague intention “to do something with the archive” soon became a mission.[10] Guided by curiosity and drawn not just to the images but to the man behind them, Asmara took up the mantle—to carry forward the story he had once hoped to tell.

Asmara’s Process: Bringing an Archive to Life

At 31, Asmara belongs to a generation far removed from when these photographs were taken. Though her mother and aunt had made an early attempt to revive the archive, it wasn’t until Asmara teamed up with Dr Tan and secured NHB’s Major Project Grant that the project gained real momentum.[11]

The manuscript presented a formidable challenge in its scope and inconsistency. “It was like trying to put together a puzzle,” she said. Some parts were typeset, others handwritten or half-digitised.[12] Images were repeated or missing; sections were dense or abruptly abandoned. Polunin had left a skeleton draft with notes on the photographs he intended to use—many of which were damaged, lost, or never digitised. He had wanted to write about topics like the seafaring practices, mudskipper trapping, or the symbolism of the coconut—but much of it existed only in fragments.[13] The work required not just editorial instinct, but emotional stamina: Asmara had to decide what to keep, what to leave out, and how to shape her grandfather’s sprawling, chaotic archive into something coherent and compelling.

Digitisation posed its own challenges. Among the more revealing finds were nearly a thousand tiny 16mm film reels—Polunin’s way of capturing movement, gesture, and fleeting detail.[14] The technical challenges were considerable: 16mm frames are minuscule and extracting high-quality stills requires exceptional precision. He had been experimenting with this for “years and years,” Asmara explained, describing how her grandfather would project footage onto a wall and film it on video.[15] In fact, his desire to extract stills from film was one of the driving motivations behind Das Buch—he saw immense potential in the moving image as visual archive.[16] Asmara picked up where he left off, combining screenshots from digitised footage with high-resolution single-frame scans.

Design was just as essential as content. Asmara and Dr Tan led the curatorial direction, but the book’s final form took shape through close collaboration with designer Karen Quek. “The layout of the images is part of the text,” Asmara said. “You read the pictures as much as the words.” Karen’s thoughtful handling of space, sequence, and scale allowed the visual narrative to unfold and tell its own story, bringing clarity and coherence to the work.

But beyond the logistics lay a deeper question: whose stories was Polunin trying to tell, and why did they matter?

Projected onto a screen, the cinefilm reels had to be reviewed manually—Asmara went through them frame by frame, combing through thousands of stills to decide which images or sequences best captured a moment or told the story most clearly. Source: Asmara Rabier

The Hidden Realm

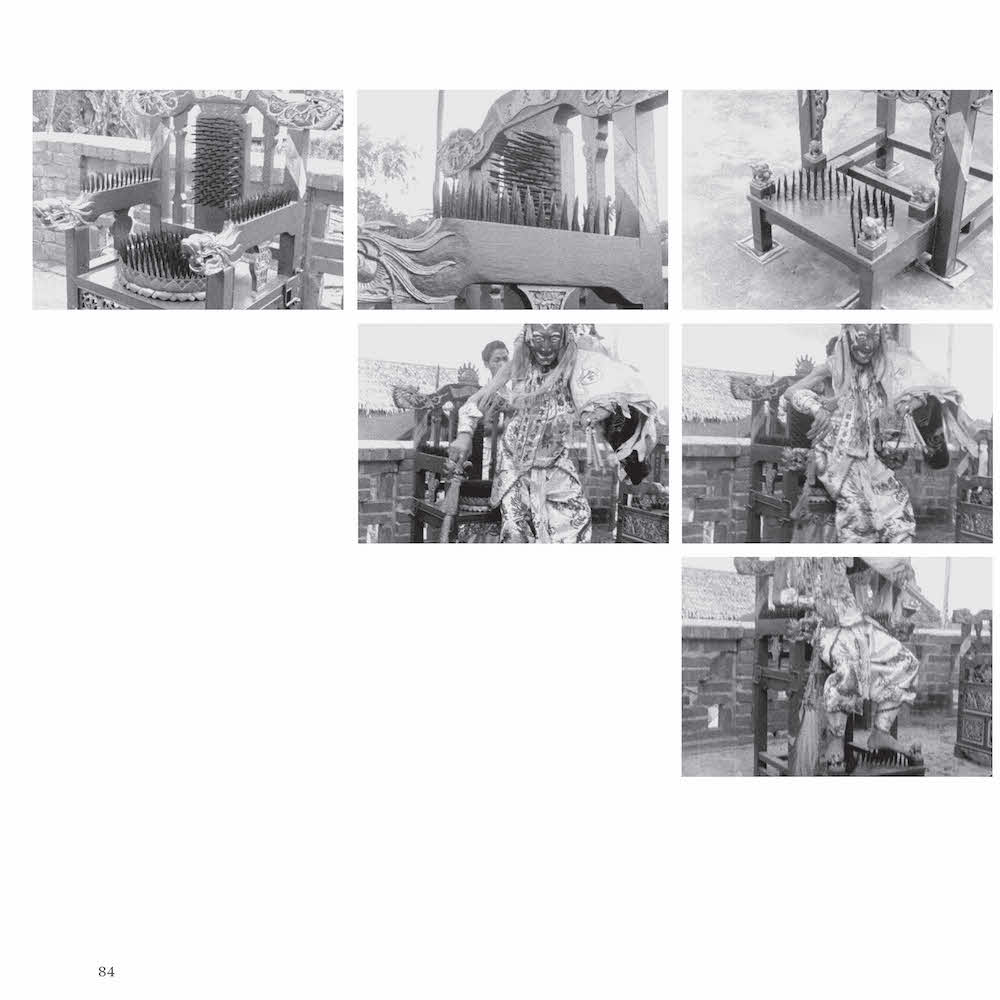

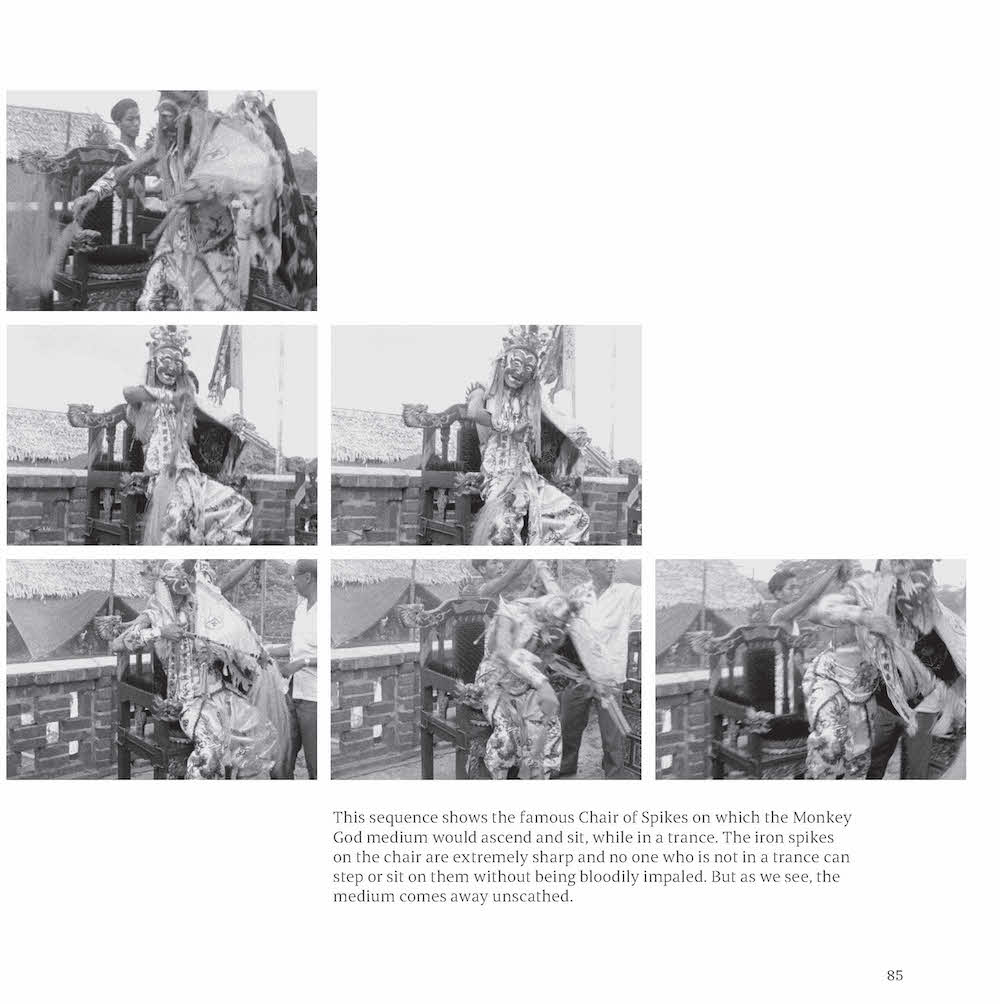

The Monkey King sequence exemplifies Polunin’s ambitious vision for cinefilm stills. This work was not just about documentation—it was his attempt to make visible the invisible, to capture a fleeting, intangible realm that he saw woven into everyday life.

Shot during a field trip to Shun Thian Keng Temple in Bukit Purmei in the early 1950s, the footage follows a temple medium as he transforms into the Monkey God, a ritual he performed regularly to help devotees with ailments and misfortunes. Polunin was fascinated by such moments—where spiritual belief, performance, and social life merged. In his words, the man was “a paradoxical mix of obvious play-actor and sincere person,” yet to the worshippers, he was the Monkey God incarnate.

Asmara’s curated stills bring that moment into sharp focus: the Monkey God listening to a devotee’s chest like a doctor or ascending the infamous chair of spikes on which the Monkey God medium would ascend and sit while in a trance. The iron spikes on the chair are extremely sharp and would impale anyone else, however the medium would come away unscathed. The sequence reveals the kind of subject Polunin was most drawn to—the hidden world of spirits that the people he encountered believed in: spirits with personalities, desires, and agency, who manifested themselves in the everyday through rituals such as this.

Changing Landscapes

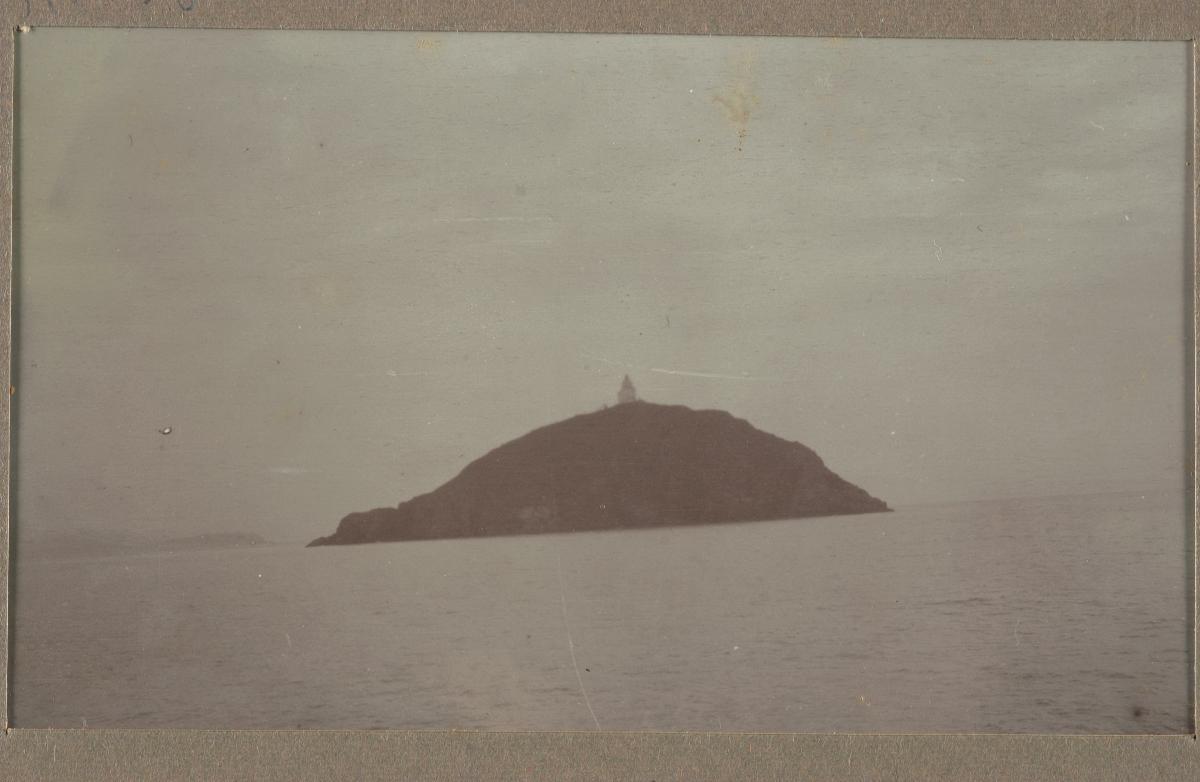

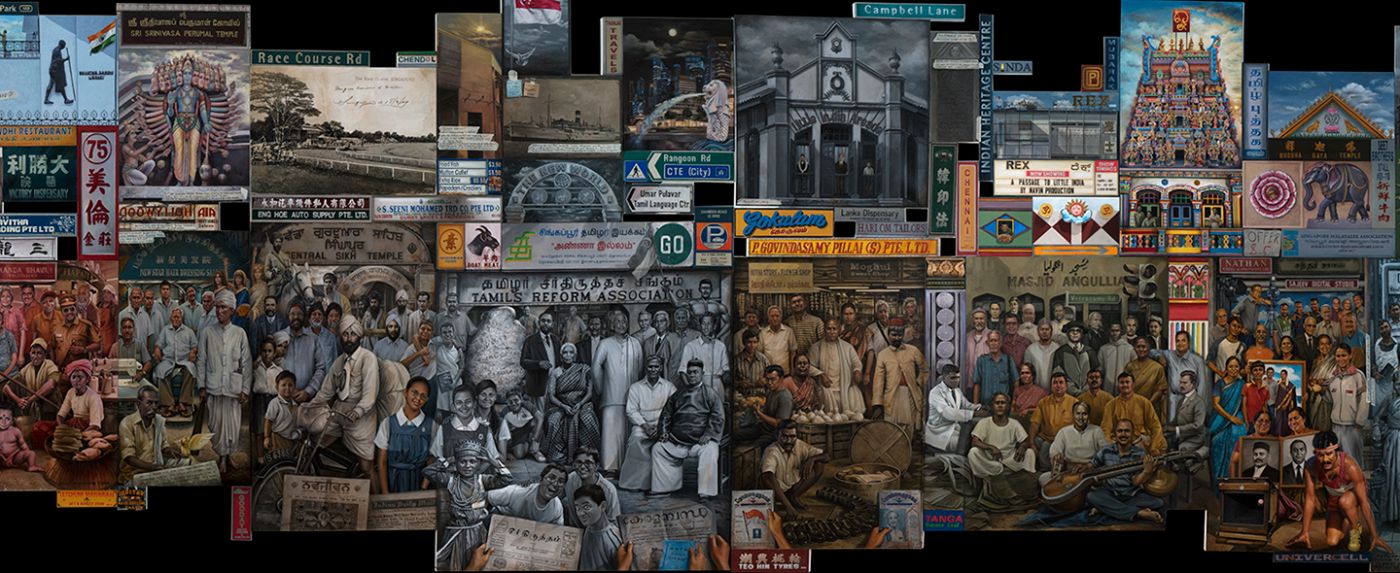

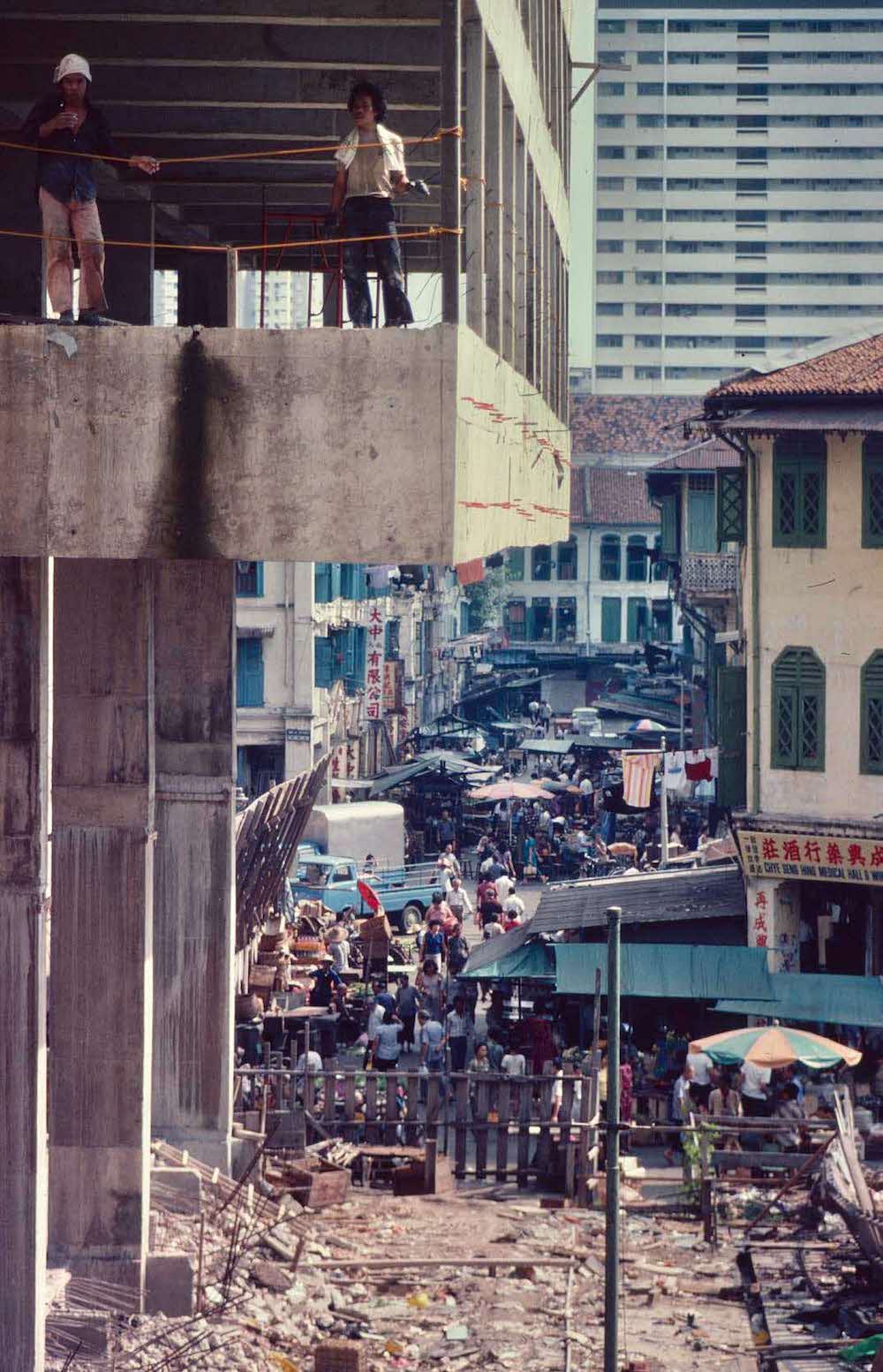

Polunin was also deeply drawn to scenes of change. Across decades of photographic work, he consistently documented Singapore’s shifting urban landscape—capturing the physical metamorphosis that accompanied its transformation into a modern city-state.

“We wanted to showcase significant changes too, like land reclamation and urban development,” Asmara noted, referring to her collaboration with Dr Tan. This approach aligned closely with Polunin’s own. Many of his photographs from the 1950s to 1980s showed demolition works or new constructions rising over old sites. This focus was fitting—Singapore during that period was in a near-constant state of flux. With the launch of Singapore’s first master plan in 1958, sweeping changes followed: kampong clearance, the building of housing estates, the expansion of roads and bridges. These were part of a broader national push toward industrialisation and economic independence, but they also meant rapid and often disruptive transformation of daily life.

Polunin’s lens captured not only the physical metamorphosis but also how communities adapted amidst this upheaval. His writing reveals a nuanced ambivalence toward progress. On Boat Quay, he described the disappearance of coolie labour and the rise of nightlife—“one can still imagine the ghosts of the boat people and their ghost barges teeming in the river.” Upstream, he observed similar shifts, recording how “the last of the stilt dwellings around Pulau Saigon are also gone,” whilst contemplating the riverside’s future appearance fifty years on.

In Chinatown, his tone sharpened. “The authentic colour and squalor of the ‘real’ Chinatown has gone,” he wrote, “but the human scene must inevitably change—or it is a dead scene indeed.”

Though reflective, Polunin did not mourn change outright. He acknowledged the new life that emerged—shophouses repurposed, families and businesses returning. Still, his writing carried a sense of ambivalence—not about change itself, but about what is lost and gained over time. His observations often straddled admiration and grief, capturing the emotional complexity of a transforming city. Asmara preserved this tone deliberately in the book. “We need to understand what it cost to get here,” she said—emphasising that the goal was not nostalgia, but clarity.

This clarity demanded more than simply quoting from his notes. Some writings were vivid and complete; others were little more than hints—a phrase on a photo, a line in a letter. She described the process as “selective storytelling,” balancing the personal without tipping into anecdote, and in places where the manuscript was incomplete, she added bridging text in a tone that echoed his own. “It was like role-playing,” she said. “Trying to stay true to how he might have said it.”

The result is a book that doesn’t just showcase change—it gives it texture. Polunin’s photographs and reflections emerge not as passive records but as thoughtful meditations on transformation. Asmara’s curation honours that complexity, allowing his conflicted, curious voice to surface again—clear-eyed, observant, and still asking questions.

The Orang Seletar: Communities and Continuity

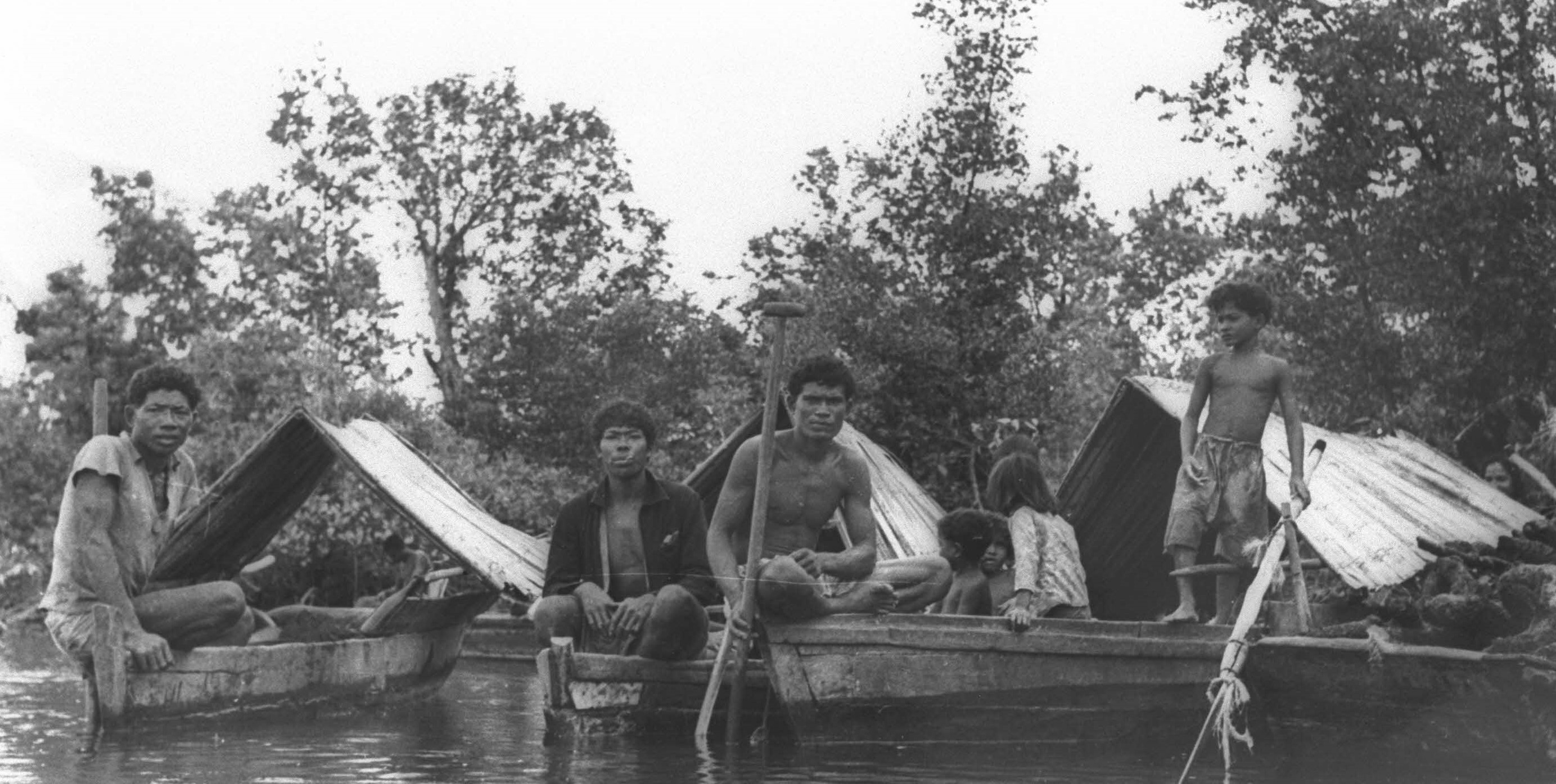

For Asmara, one story felt especially personal: that of the Orang Seletar. Beginning in the 1950s, Polunin worked closely with a small community of around 7 to 10 individuals—mostly immediate family members of the headman, Tok Batin Buruk.[17] He first arrived as a doctor, conducting health surveys, but his camera was never far.[18] The photographs, initially part of his medical work, soon took on a life of their own. As part of his ongoing research, Polunin returned regularly—and each visit deepened his familiarity with the people and their rhythms. Over time, he captured something rare: an intimate portrait of a community across time.

The images from this period are tender—children laughing, families mid-conversation, quiet gestures aboard houseboats nestled in the mangrove-fringed north of Singapore. He documented their everyday world: fishing, crabbing, travelling by water. The same faces reappear, aging over time. “You almost experienced time with this one group of people,” Asmara said. Clothes change, landscapes shift, moods evolve. “There are so many details that most people would not notice,” she reflected. “But it’s there to be noticed. You could stare at a picture and discover something new every time—something interesting happening in the background.[19]

Decades later, Asmara travelled to the same villages—such as Sungai Temon, just across the Causeway—to reconnect with the community and identify people in the photographs. “It really brought the whole project to life,” she said. With help from Jefree Salim and his mother, Ibu Leti Akon, who recognised many of the faces—“that’s Uncle so-and-so, he was a baby then, now he’s headman of the village”—Asmara encountered something the rest of the archive couldn’t offer: direct, living memory. It was the only chapter where she could engage not just with material, but with descendants of those photographed. “It was invaluable,” she said. “I wish I could have done it with everyone.[20]

This community held special significance for her family. One of Asmara’s last trips with her grandmother was to visit the village for the opening of a community centre, where Polunin’s photographs still hang. That centre remains, though the community now faces new threats—once again labelled squatters, once again caught in the tide of land development.[21]

Ivan Polunin, Wak Me, wife of the headman, with their children. Entil, the young boy, is now the current headman of Pasir Putih village (1950s).

Conclusion: A Portrait in Relation

In the process of making the book, Asmara did not just recover an archive—she uncovered a person. “I got to see him not just as my cute grandfather,” she said, “but as a man in his prime.” One of her biggest revelations was the quiet, constant presence of her grandmother, Siew Yin—Polunin’s wife and lifelong collaborator. “She packed his bags, carried the cameras, typed the manuscripts… even knitted the nets he used to catch fireflies,” Asmara recalled. Siew Yin was there on field trips, behind the scenes, beside him in the dark mangroves and back home at the writing desk. It was her unseen labour that made the scale and ambition of his work possible. “It suddenly made sense,” Asmara said. “I understood how he did so much—because she was right there, doing it with him.[22]

The journey was deeply personal for Asmara. “We were very close,” she shared. Polunin passed away when she was sixteen. She had joined him on a few trips and knew of his work, but their conversations about it were always surface level. “He gave me my first camera,” she recalled, “but I never quite figured out how to use it.” It wasn’t until she began sorting through his archive—boxes of film, fragments of writing, decades of images—that she began to see him differently. “I got to see him in his prime,” she said. “I learned so much about how he thought, what drove him. It changed how I understood him.[23]

The resulting book makes no claim to be a definitive account of Singapore’s past. Instead, Asmara sees it as something else: an intimate portrait. It captures not just Polunin, but a larger web of relationships—those who walked beside him, supported his work, and carried his legacy forward. In her words, it represents “not the objective truth, but a way of showing what a certain aspect of the past was like.[24] It tells the story of one man, his world, and the forces that shaped both.

Once Upon an Island was finally published in 2023—an archive completed not by closure, but by connection.

Polunin and Siew Yin on their wedding day in 1959. Source: Dr. Ivan Polunin

Siew Yin accompanying Polunin in the field with sound recording equipment. Source: Dr. Ivan Polunin

This project was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Major Project Grant.

Notes

[2] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 418-420.

[3] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 424.

[4] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 378-380.

[5] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 427.

[6] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 9.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Asmara Rabier, The Making of Once Upon an Island (Unpublished), interview by Jaclyn Chua, Audio recording, 26 February 2025.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Rabier, The Making of Once Upon an Island (Unpublished).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 391.

[17] Polunin, Once Upon an Island. 316.

[18] Rabier, The Making of Once Upon an Island (Unpublished).

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Rabier, The Making of Once Upon an Island (Unpublished).

[23] Rabier, The Making of Once Upon an Island (Unpublished).

[24] Ibid.