+65 Volume 2 – 2022

Text by Karen Ho Wen Ee

Read the full +65 Vol. 2

My evening runs through Jurong take me through a network of factories. There

is an oil refinery a few kilometres away, with Jurong Island located just

beyond. Yet the sky here is no less blue than in any other neighbourhood, with

no fewer birds or trees. This clean air, however, belies Singapore’s

heavy reliance on industrialisation which has powered our economy since the

1960s. In fact, it is a testament to careful planning right from the early

stages of Singapore’s post-independence development.

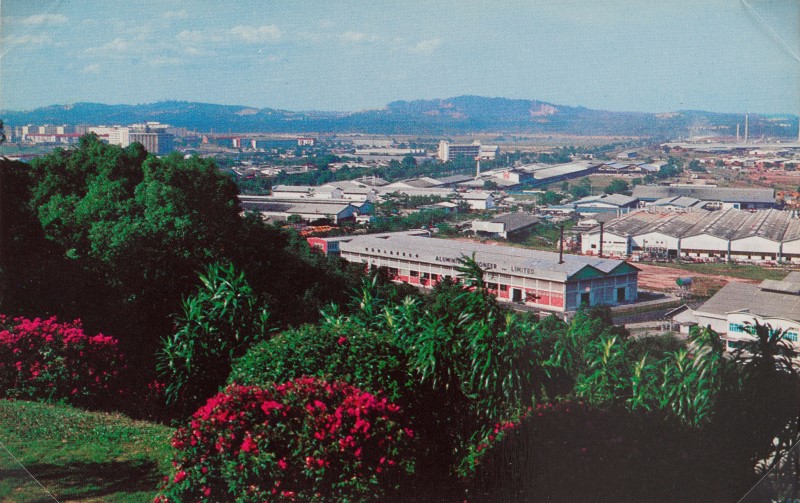

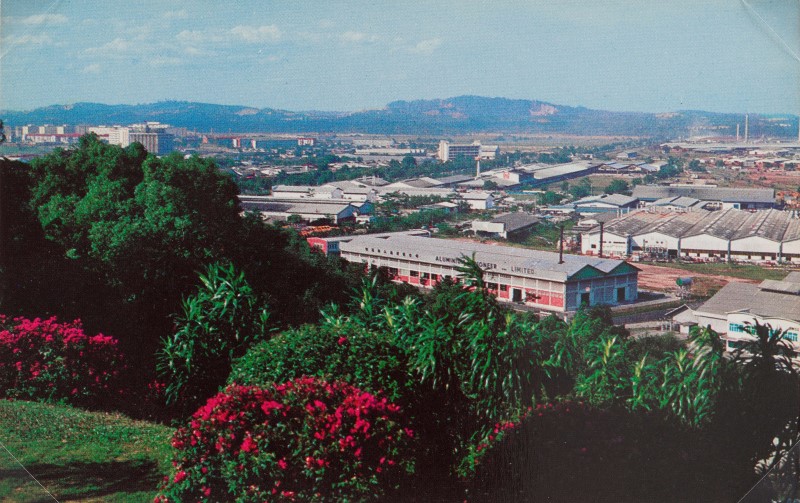

Jurong Hill and Jurong Industrial Estate, 1970. Collection of the

National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Jurong Hill and Jurong Industrial Estate, 1970. Collection of the

National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

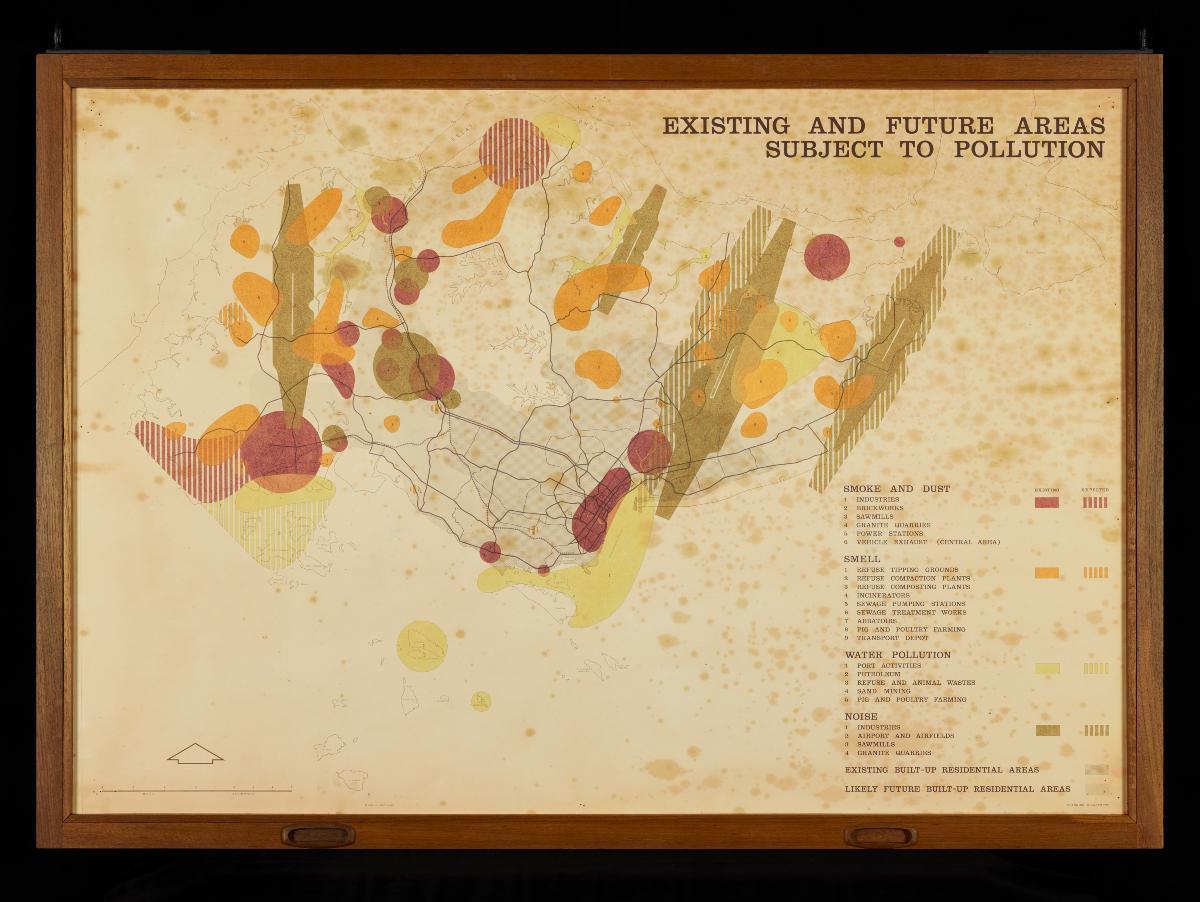

A clue to these early plans lies in the former office of Singapore’s

founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew. Near his desk, a cabinet houses a

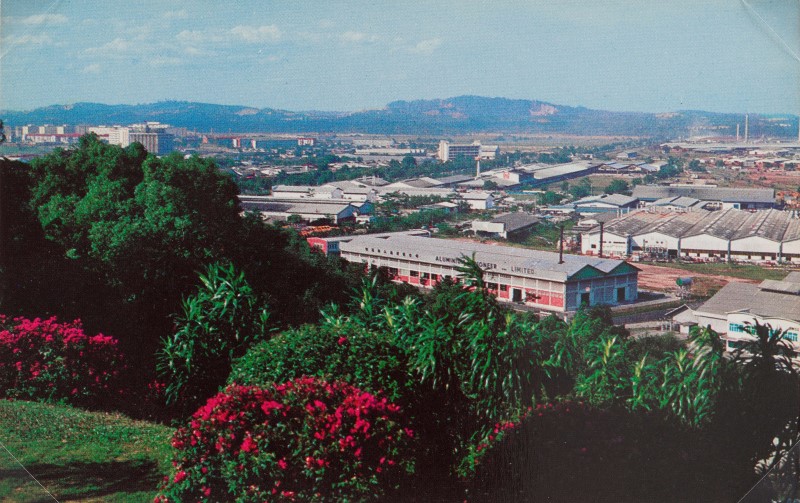

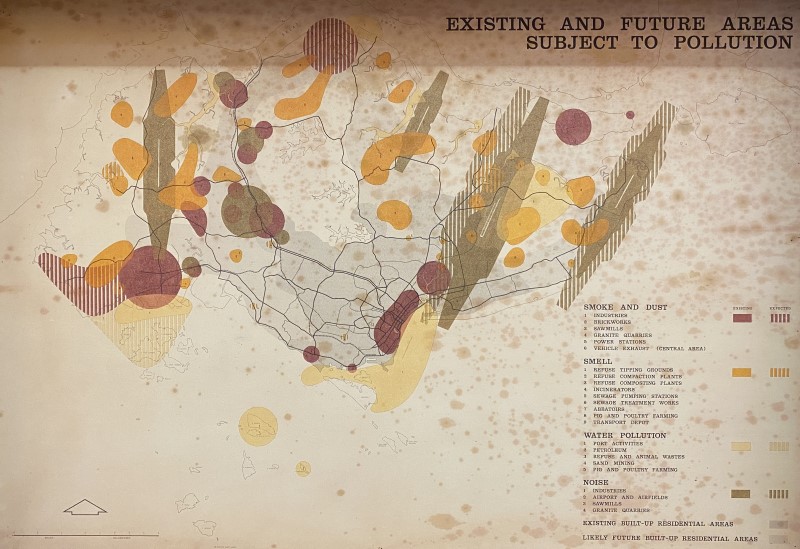

series of large, detailed maps. One map, titled “Existing and Future

Areas Subject to Pollution”, dates to the early 1970s and indicates

existing and expected sites of pollution in Singapore such as Jurong and

Sembawang. The fact that this map was drawn up and hung in Mr Lee’s

office indicates that the issue mattered greatly to him, even during the

initial stages of Singapore’s industrialisation. What prompted this

focus on pollution, and what was done about it? This article explores how

Singapore approached and tackled this environmental challenge during our early

nation-building years through the establishment of the Anti-Pollution Unit.

Map titled “Existing and Future Areas Subject to Pollution”

located in the former office of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew,

1970s. Courtesy of Prime Minister’s Office.

Map titled “Existing and Future Areas Subject to Pollution”

located in the former office of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew,

1970s. Courtesy of Prime Minister’s Office.

Anti-Pollution Unit: The Beginning

In the 1960s, Singapore embarked on a rigorous industrialisation programme to

boost economic development. As public housing became located closer to

industrial areas, residents complained about pollution such as smoke, dust,

and fumes that came from the factories. At that time, the responsibility of

enforcement was divided among two departments, the Public Health Engineering

Branch and Environmental Health Department. However, existing guidelines to

address air pollution were vague and regulation were ineffective.1

In February 1970, the government invited World Health Organisation consultant

Graham Cleary to Singapore to assess the situation and recommend an action

plan. His recommendations included establishing a specialised Air Pollution

Unit, developing legislation for air pollution control and factoring air

pollution considerations into urban planning.2

Although air pollution levels in Singapore were generally within global

standards and lower than other industrialised cities, there would be problems

down the road if prevailing growth rates were maintained.3 Lee Ek

Tieng, the first Head of the newly established Anti-Pollution Unit (APU),

recalled then-Prime Minister Lee being “very concerned” about the

pollutive impact of industrialisation after having read Cleary’s report.

Within two months of Cleary setting foot in Singapore, APU was established

under the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) before formally gaining

Parliament’s stamp of approval the year after.4

The Economic Development Board’s flatted factory at Tanglin Halt

Industrial Estate being constructed, with public housing in close

proximity, 1965. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy

of the National Archives of Singapore.

The Economic Development Board’s flatted factory at Tanglin Halt

Industrial Estate being constructed, with public housing in close

proximity, 1965. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy

of the National Archives of Singapore.

With other reforms to tackle land and water pollution such as the

Environmental Public Health Act, the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea Act,

and even the “Keep Singapore Clean” campaign, APU focused on

curbing air pollution, ultimately aiming to play a preventive rather than

retroactive role. Tan Guong Ching, who started his public service career in

APU as an engineer, later commented: “If we had not placed our control

measures right from the very beginning, Singapore would have been a totally

different place—a very polluted place.”5

“I was looking out of my office window at Pearl’s Hill one

day and I thought the rains were coming. But on taking a closer look, I

realised that the murkiness was smog … I asked myself: if Singapore

did not take this thing in hand now, what would happen in the

future?”

Lim Kim San, Singapore’s first Minister for the Environment, as

quoted in Forging a Greener Tomorrow

Finding Their Way

As tackling industrial pollution was just in its early stages worldwide,

little research data was available, especially for tropical climates like

Singapore’s. The Unit thus had to conduct its own experiments to measure

the impact of air pollution here and find its own solutions. For instance, it

needed to find out whether temperature inversions—a

phenomenon where cold air is trapped under warmer air, keeping pollutive

particles trapped as well—occurred at night in Singapore,

as in temperate climates. To measure this, the team attached temperature

sensors along the chimney of the Senoko Power Station in Sembawang, day and

night. They found that temperature inversions did indeed occur in Singapore,

and revised the guidelines for chimney heights to ensure that any pollutive

emissions would not remain trapped.7 While APU’s methods were

initially manual and rudimentary, Joseph Hui, who joined APU as an engineer in

1977 and eventually became Deputy CEO of the National Environment Agency,

remarked that being closer to the ground gave the team “a sense of

satisfaction for being able to protect the environment”.8

Liu Kang, Working at the Brick Factory, 1954. Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 128.6 cm. Gift of the artist’s

family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Liu Kang, Working at the Brick Factory, 1954. Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 128.6 cm. Gift of the artist’s

family. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

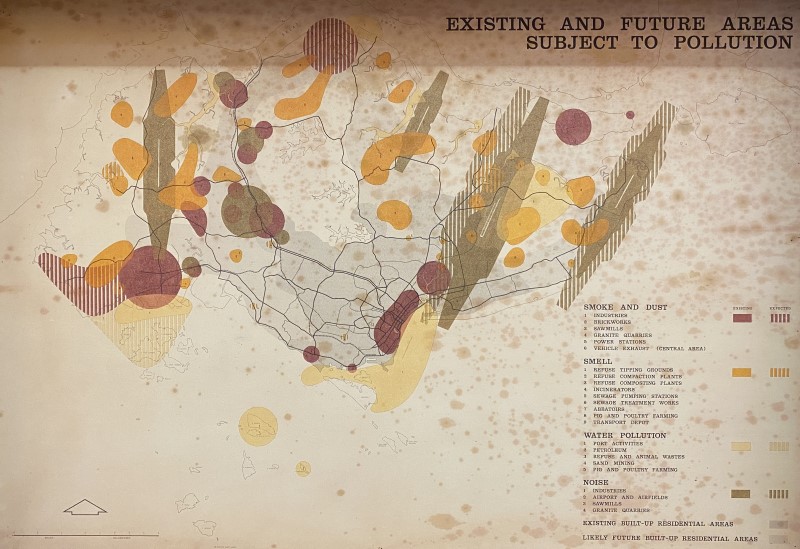

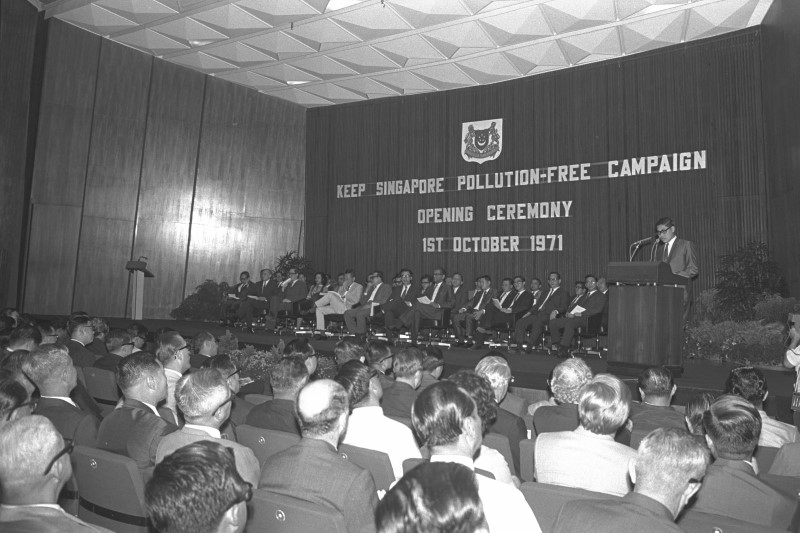

Visitors at the “Keep Singapore Pollution Free” campaign

exhibition held at the Singapore Conference Hall, 1971. Ministry of

Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of

Singapore.

Visitors at the “Keep Singapore Pollution Free” campaign

exhibition held at the Singapore Conference Hall, 1971. Ministry of

Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of

Singapore.

The team also relied strongly on the global community to build up its

expertise. As the first head of APU, Lee Ek Tieng completed a seven-month

attachment in New Zealand and Australia in 1970 before returning to assume his

position full-time. Subsequently, Singapore continued to engage these two

nations closely, and as the three countries engaged in mutual dialogue,

solutions such as new pollution control technology were jointly developed.9

Standing Their Ground

Having consulted advisors and gathered data, APU prepared to implement new

anti-polluting regulations. Although these measures were unpopular with many

investors and firms, the authority accorded to APU as an agency under

PMO’s ambit enabled it to stand its ground.

Before proper legislation was introduced, APU had sought assistance from other

departments such as the Ministry of Labour and Registry of Vehicles to manage

emissions; however, enforcement often seemed like a “cat-and-mouse

game” due to polluters’ evasive tactics and shortage of regulatory

staff.10 The Clean Air Act and Clean Air (Standards) Regulations,

passed in 1971 and 1972 respectively, subsequently gave the Unit greater

power. APU would screen all factories with potentially pollutive impact before

allowing them to operate, and industries whose pollutive risk was too great

were turned down. For example, an attractive offer by an Australian firm to

set up an iron and steel plant was rejected. Existing factories also had to

comply with new regulations by installing pollution control equipment such as

venturi scrubbers, or by changing practices such as inefficient combustion

techniques and pollutive waste management methods.11

To keep residential neighbourhoods pollution-free, APU also developed a zoning

system that sorted industries according to their pollutive

impact—a new strategy that was subsequently implemented by

other countries.12 Industries were categorised by indices that

evaluated the amount of noise generated, the pollution potentially produced

and the type of equipment involved. “Light Industries” that did

not create air, water, or noise pollution could be situated near homes, while

“Special Industries”—which ranged from the

manufacture of ceramic tiles to petroleum refineries—faced

pollution control measures and were situated in dedicated zones.13

Some existing factories were forced to relocate, but the advantage was that

those with outdated equipment moved into newer premises with better pollution

control facilities.14

On how companies reacted to APU’s guidelines, Tan Guong Ching recalled

in an interview with the Founders’ Memorial: “Of course they

didn’t like it. It meant cost to them.”15 Indeed, the

new measures were an impediment to foreign investment and some industries

moved out of Singapore altogether. Still, then-Minister for the Environment

Lim Kim San understood that the costs of pollution could be even greater than

the economic benefit from these investments.16

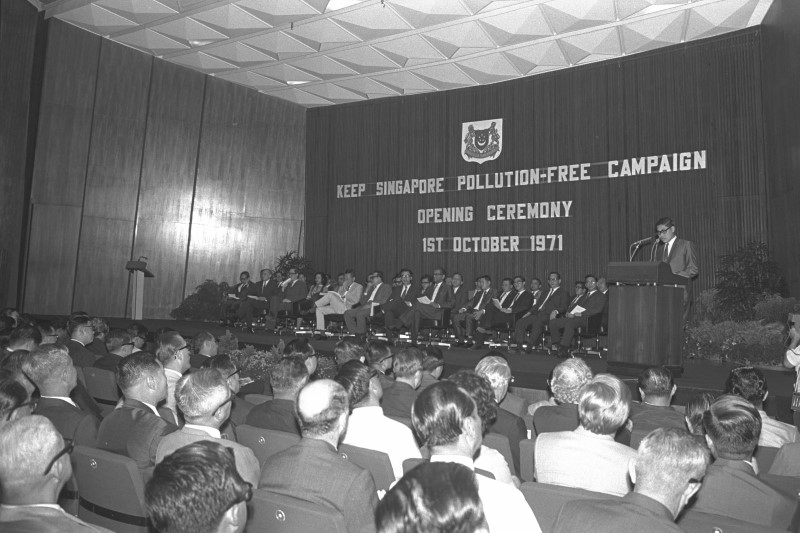

Minister for Health Chua Sian Chin speaking at the opening of “Keep

Singapore Pollution Free” campaign held at the Singapore Conference

Hall, 1971. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of

the National Archives of Singapore.

Minister for Health Chua Sian Chin speaking at the opening of “Keep

Singapore Pollution Free” campaign held at the Singapore Conference

Hall, 1971. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of

the National Archives of Singapore.

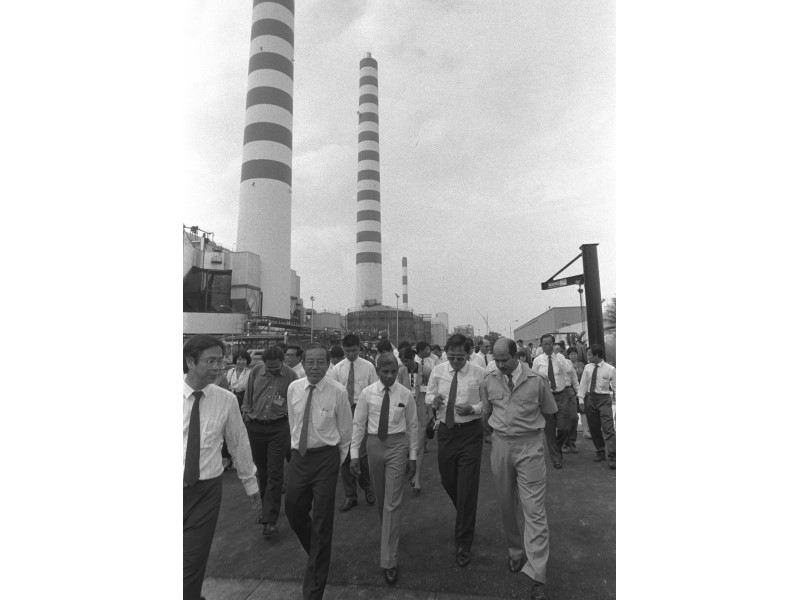

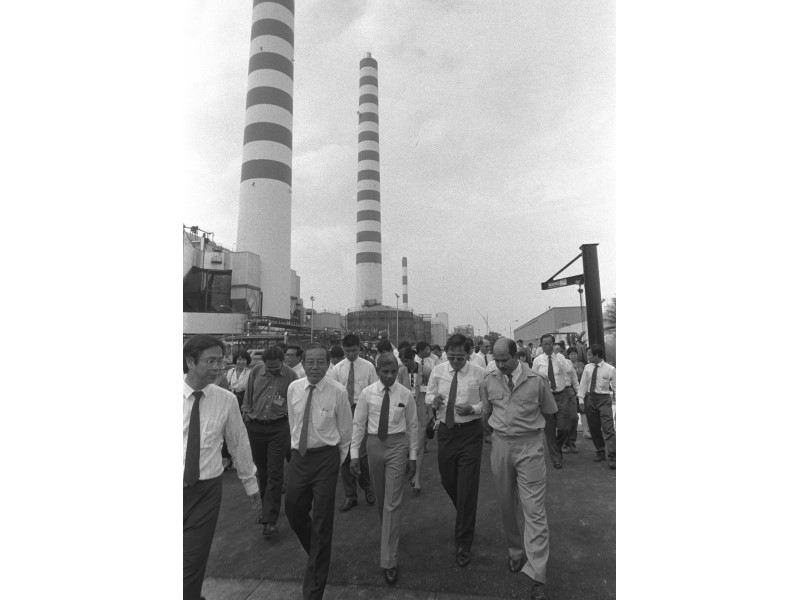

Minister for National Development S. Dhanabalan at Senoko Power Station,

1992. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the

National Archives of Singapore.

Minister for National Development S. Dhanabalan at Senoko Power Station,

1992. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the

National Archives of Singapore.

The fact that APU reported directly to the Prime Minister also gave it the

authority needed for enforcement. In an interview with the National Archives

of Singapore, Lee Ek Tieng recounted an incident where a large petrochemical

company, upon needing to install a ground flare system for pollution control,

“complained to everybody, every minister… they even appealed to

Goh Keng Swee.” Lee added, “Goh Keng Swee was very clever, left it

to the Prime Minister. That was it. And they never got away. They finally had

to put a ground flare.”17

“Actually environmental pollution was quite a new topic … we

were among the pioneers of pollution control. So we had a lot of, shall I

say, experimentation … we thought through the problems and

solutions ourselves.”

-

Tan Guong Ching, in a 2007 interview with the National Archives of

Singapore18

Minister for Finance Hon Sui Sen checking out Philips’ SO2 air

pollution monitor, which was presented by Philips Singapore during the

opening of Philips Machine Factory and Telecommunications Factory in

Jurong, 1973. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of

the National Archives of Singapore.-

Minister for Finance Hon Sui Sen checking out Philips’ SO2 air

pollution monitor, which was presented by Philips Singapore during the

opening of Philips Machine Factory and Telecommunications Factory in

Jurong, 1973. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of

the National Archives of Singapore.-

“We are here interested in prevention before the situation gets out

of hand … It is therefore not pre-mature to control air pollution

now as some people think it is in Singapore. Industrialists and other

polluters must think and accept that air pollution control is part of

their responsibility.”

Anti-Pollution Unit, in a 1971 publication titled Air Pollution in

Singapore

Opening of Pan-Malaysia Industries Ltd’s plywood factory at Jurong

Industrial Estate, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection,

courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Opening of Pan-Malaysia Industries Ltd’s plywood factory at Jurong

Industrial Estate, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection,

courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Then-Head of APU Lee Ek Tieng at a laboratory during his attachment in

New Zealand, 1970. Courtesy of Archives New Zealand.

Then-Head of APU Lee Ek Tieng at a laboratory during his attachment in

New Zealand, 1970. Courtesy of Archives New Zealand.

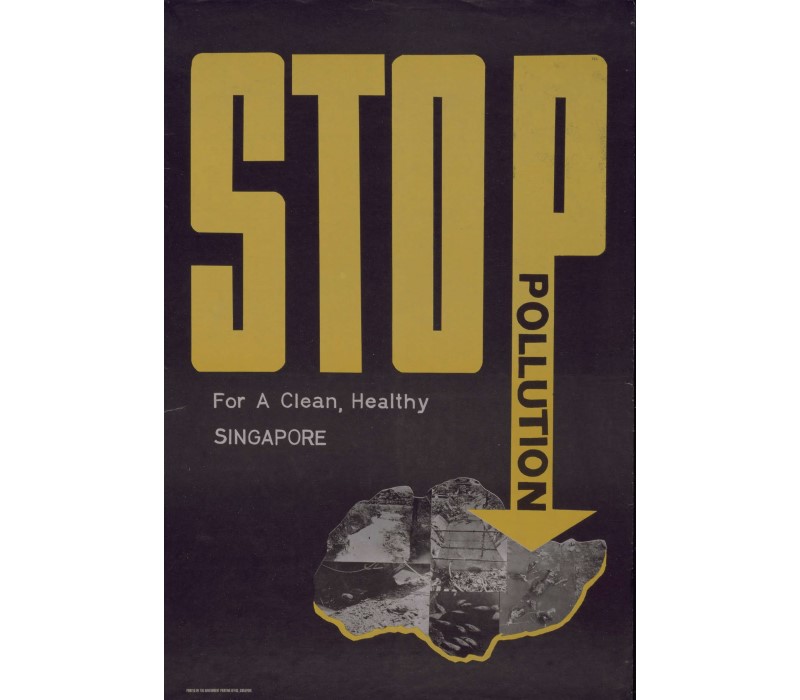

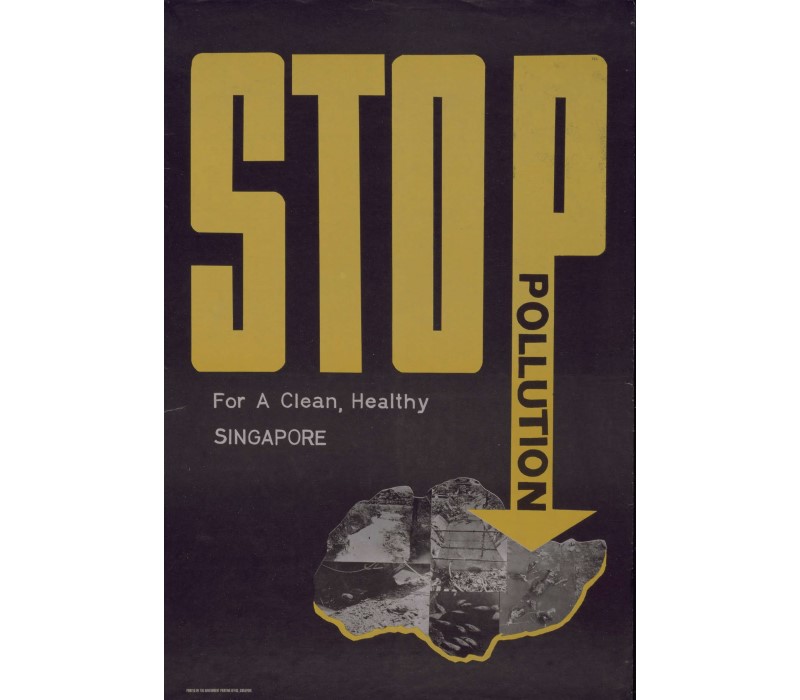

Poster titled “Stop Pollution: For a Clean, Healthy

Singapore”, 1977. Ministry of the Environment Collection, courtesy

of the National Archives of Singapore.

Poster titled “Stop Pollution: For a Clean, Healthy

Singapore”, 1977. Ministry of the Environment Collection, courtesy

of the National Archives of Singapore.

Conclusion

APU’s establishment in 1970 marked the beginning of greater

environmental awareness and action in Singapore. In 1972, Singapore became one

of the first countries in the world to form a ministry dedicated to the

environment, under which APU was eventually subsumed in 1983.20

In Singapore’s early post-independence years, environmental protection

was more about understanding the impact of pollutive activity and keeping

these effects at bay. Recent conversations have moved towards the protection

of wildlife and nature from human activity and the sustainable use of

resources. While Singapore today looks to greening and reducing overall

environmental impact, APU’s spirit of experimentation and collaboration

remains ever-relevant. The Unit’s persistence in implementing

anti-pollution measures paid off in the clean environment we enjoy today;

similarly, one can expect the present generation’s commitment to

furthering environmental consciousness to have a palpable impact on our

future.

Karen Ho Wen Ee is a Yale-NUS History graduate with an interest in the

stories that make up Singapore. She currently works at a media monitoring

firm and embarks on writing projects in her spare time. This article was

written when she was Assistant Manager (Curatorial and Engagement) at the

Founders’ Memorial.