TL;DR

Singapore’s hawker culture evolved from unregulated street food vending in the 1800s to today’s organised hawker centres. The trade grew with immigration, serving as an employment option and providing affordable food to workers. Despite its economic benefits, unregulated hawking caused public health and congestion issues. Post-independence, the government implemented comprehensive reforms from the 1970s onwards, transforming street hawking into the current system of permanent food centres which eventually came to form the basis of Singapore’s hawker culture.The History and Characteristics of Modern Hawking

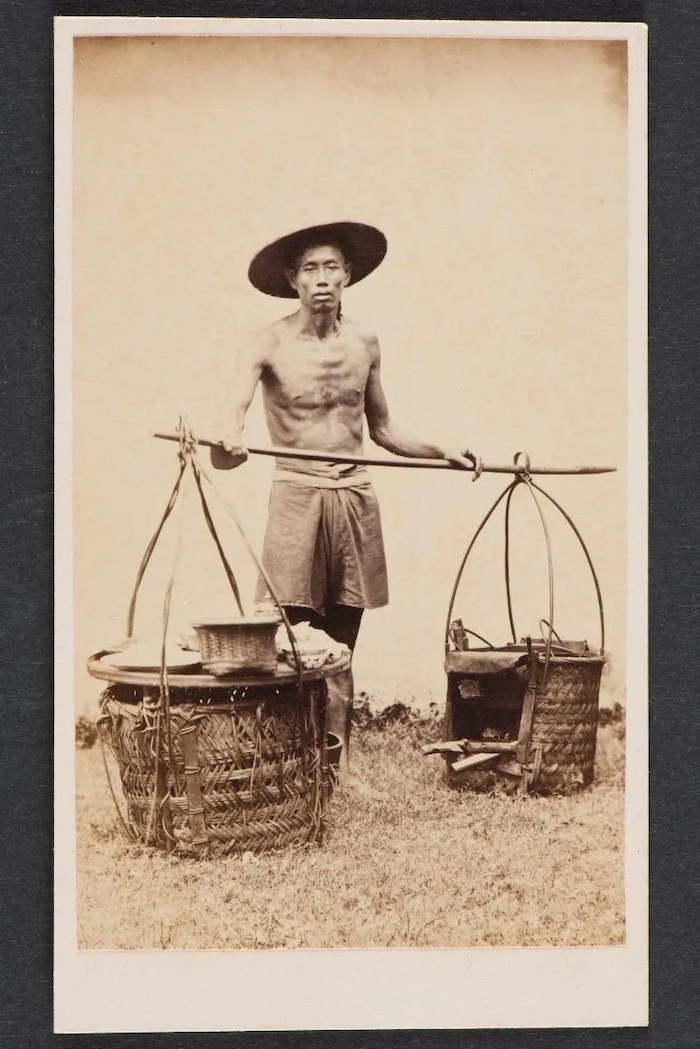

The modern history of hawking in Singapore traces back to the early 19th century, alongside the establishment of British colonial rule. As Singapore developed into a major entrepôt trading hub, waves of Chinese and Indian immigrants arrived, driving a sharp rise in the island’s recorded population—from approximately 150 in 1819 to around 10,000 by 1822.

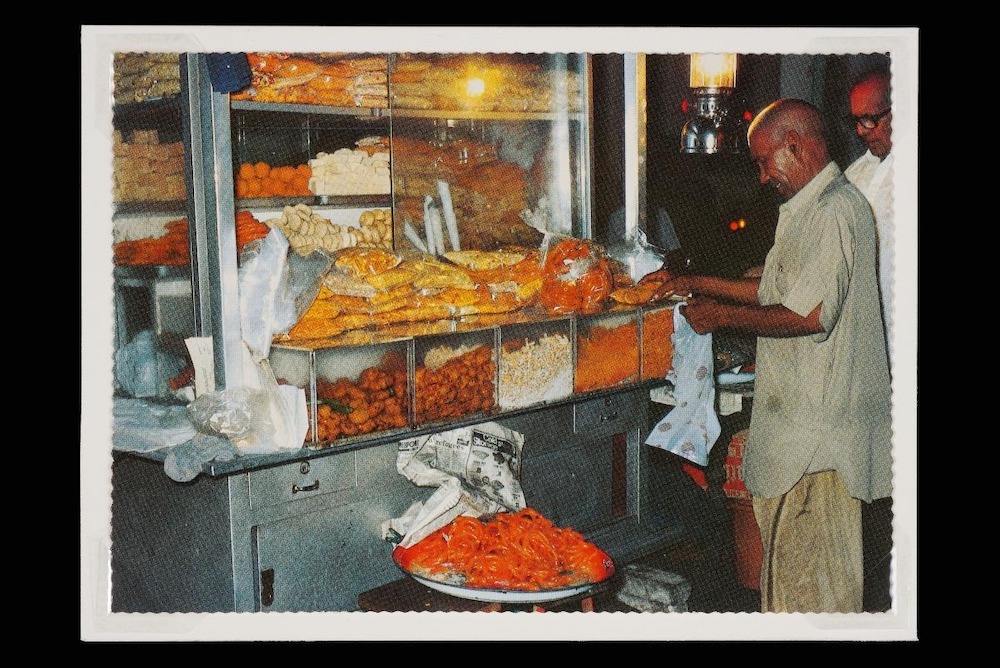

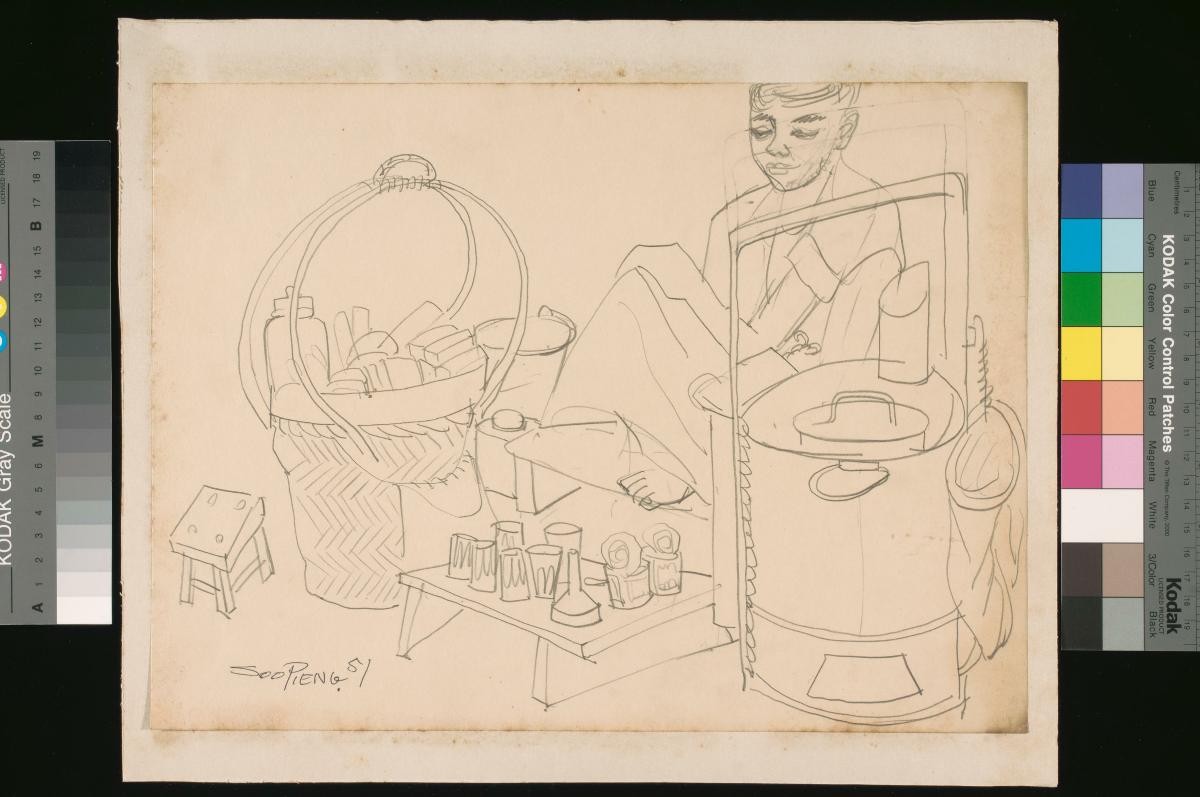

As Singapore’s population flourished, so too did hawking, driven by two key socioeconomic factors. First, hawking served as an attractive transitory vocation due to its low barriers to entry and largely unregulated nature. Immigrants in structural or frictional unemployment often turned to hawking as a temporary means of livelihood, selling simple fare on the streets until better or more permanent job opportunities emerged. Second, there was strong demand for cheap and accessible food among immigrant labourers. The majority of Singapore’s working population at the time were predominantly male immigrants aged 15 to 59 with little time to cook, and with little to no family support structures to fall back on. Thus, hawkers played a critical role in meeting their dietary needs, particularly during midday meals around docks and business districts.

Naturally, the demographic composition of hawkers reflected the boom in Chinese and Indian immigration. According to the Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission (1950), Chinese hawkers made up 84% of the hawker population, followed by Indian hawkers at 14% and Malay hawkers at 2% (see Figure 1 and 2).[1] Proportional to one’s race, Indians were the most likely to become hawkers, and Malays were the least likely. Scholars such as Syed Hussein Alatas have suggested that the relatively low participation of Malays in the labour market (consequently hawking) may be attributed to their entrenchment within subsistence networks—such as agriculture, fishing, and extended family—which offered alternative means of livelihood.[2] In contrast, immigrants, lacking such support structures, were more dependent on colonial labour or self-employment, including hawking.

Figure 1 – Ethnic Breakdown of Hawkers in Singapore, 1950

| Race | Total Population | Racial Breakdown of Population (%) | Hawkers by Race (%) | Propensity of the Race to Undertake Hawking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 789,160 | 77.7% | 84% | 1.1 |

| Malay | 123,624 | 12.2% | 2% | 0.2 |

| Indians | 72,467 | 7.1% | 14% | 2.0 |

| Others | 30,202 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note: There are no numbers for “Others” as the 1950 Commission did not record hawkers of other ethnicities categorised as “Others”. Figures rounded up to 1 decimal place.

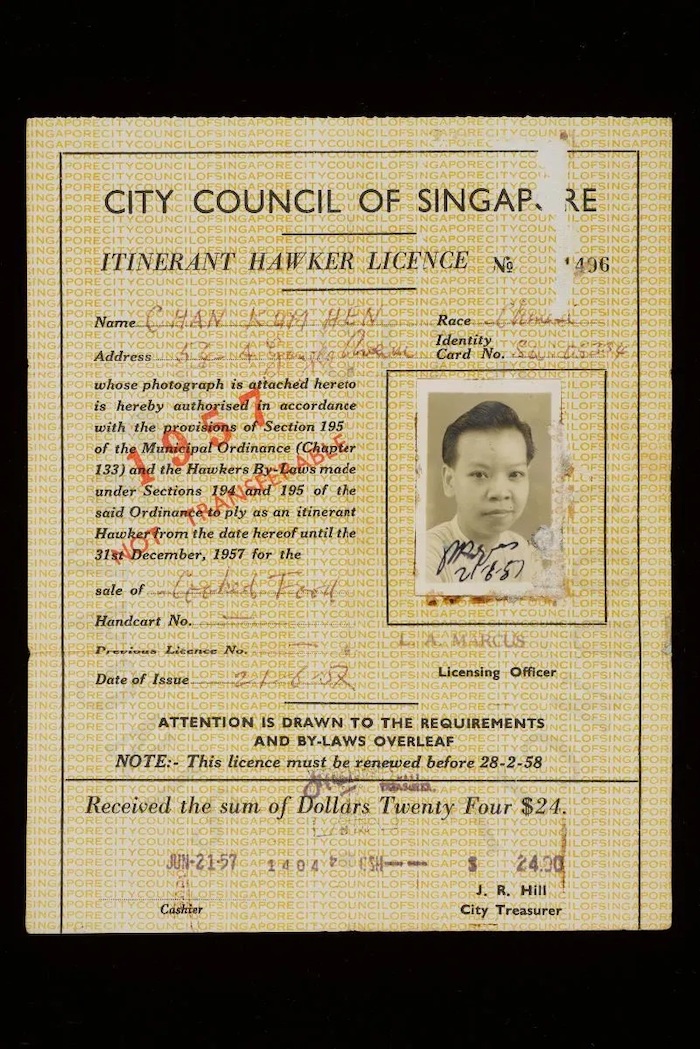

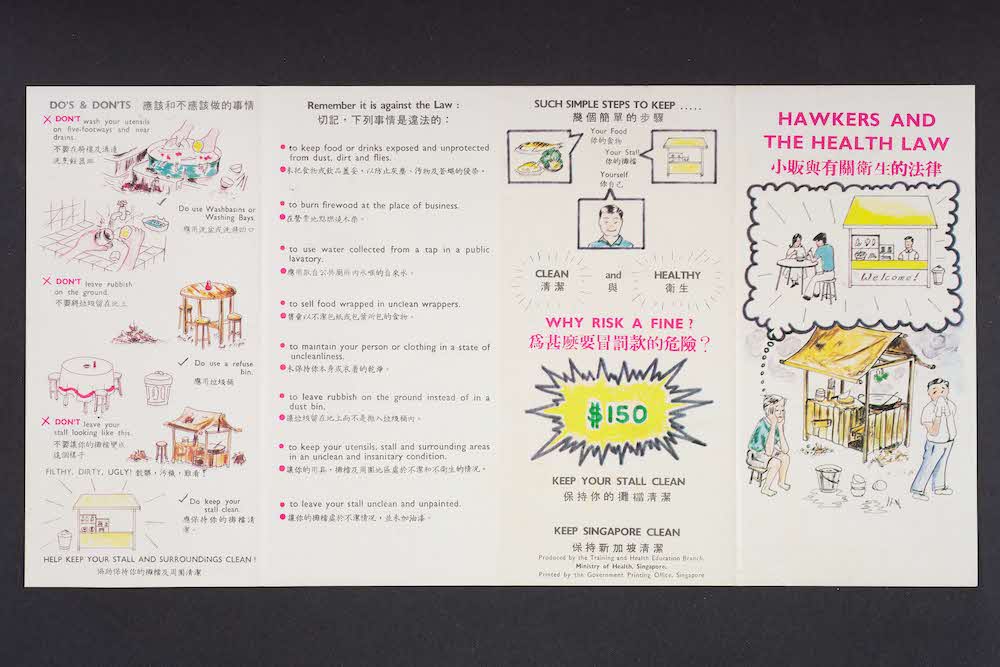

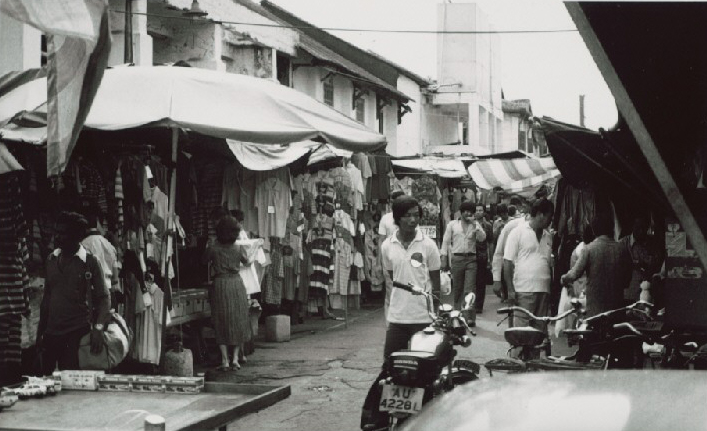

Source: Kueh 2024, 103Hawker Problem and its Solutions

Despite its socioeconomic utility, itinerant and unregulated hawking posed significant administrative challenges. Hawkers were frequently associated with public health risks, contributing to the spread of diseases such as cholera and typhoid due to unsanitary practices—such as using contaminated water for food preparation and dishwashing—and improper waste disposal. Additionally, hawking disrupted urban planning efforts. Their unregulated and spontaneous operations often led to clustering around high-traffic areas like the Central Business District, resulting in congestion for both pedestrians and vehicles. Early regulatory efforts, including the introduction of the first hawker by-laws in 1907 and their subsequent expansion in 1919, proved largely ineffective. Enforcement was limited, and non-compliance among hawkers remained widespread.[3]

The ballooning post-war hawker situation, from about 11,000-17,000 in the early 1930s to 30,000 in 1947, prompted the City Council to launch the Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission (1950), Singapore’s first comprehensive survey of hawkers. The Commission confirmed that the widespread hawking was primarily driven by (1) economic necessity and (2) a general lack of employment opportunities, noting that “hawking is a result of unemployment and economic distress…to provide an alternative means of livelihood in the event of such disasters are merest common sense."[4] Surveys from the Commission support this finding, with approximately 70% of surveyed hawkers (around 17,500) taking up the trade during or after the war.[5]

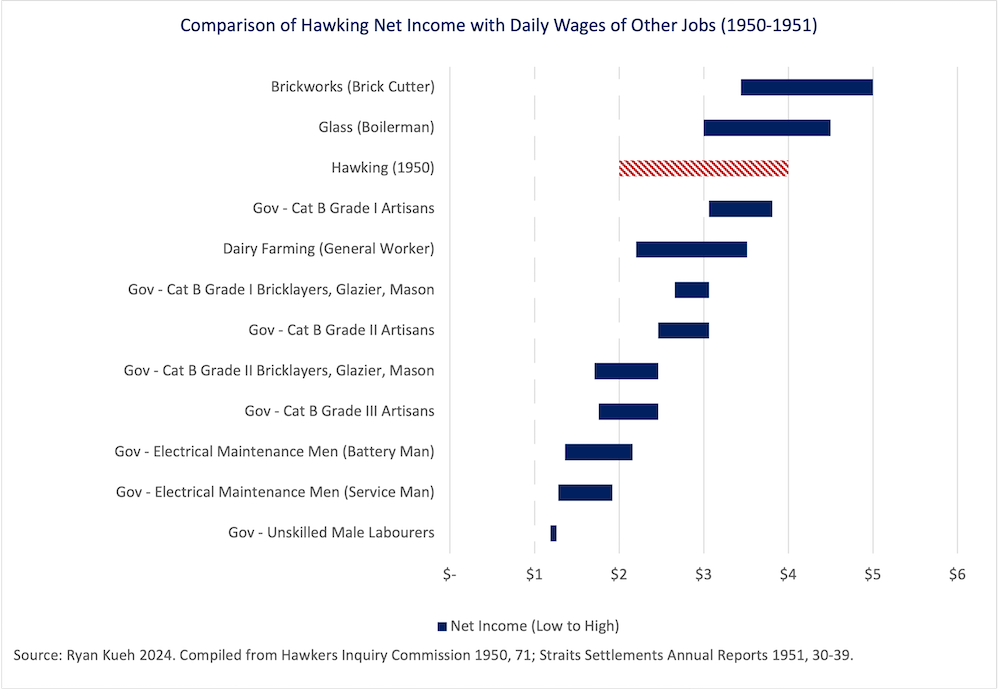

Hawking also offered higher earnings than most formal jobs available at the time. A comparison of a hawker’s potential net income with the daily-rated wages of other available jobs shows that hawking was indeed one of the most profitable vocations (see Figure 3). This was further compounded by the low levels of education and skills among the population. More than half of the surveyed hawkers were unable to read or write in any of the four official languages—English, Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil—with fewer than 1% able to read or write in English.[6] Hawking thus became a natural stop-gap vocation: accessible, and often more lucrative given the circumstances. These long-term economic factors added to the complexity of effectively addressing the hawker issue in Singapore.

Figure 2 – Hawker Population Density in Singapore, 1931-1978

| Year | Hawkers | Population | Hawker Population Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 12,000 | 562,866 | ~2.17% |

| 1947 | 29,764 | 938,144 | ~3.17% |

| 1950 | 25,000 | 1,015,453 | ~2.46% |

Note: Numbers for 1931 are for licensed hawkers. Numbers for 1947 onwards include both licensed and unlicensed hawkers. It would be prudent to note that the number of (licensed) hawkers would most likely be underreported given the transient and itinerant nature of hawkers.

Source: Kueh 2024, 12

Figure 3 – Net Income of Hawkers Compared to Other Occupations, 1950

Source: Kueh 2024, 60

Independence and Hawker Reform (Phase 3)

Singapore’s independence in 1965 marked a watershed moment for the nation—and for the hawker industry. For the new government, the continued persistence of hawker-related issues symbolised broader economic and governance challenges that needed urgent attention.

First, itinerant and unregulated hawking posed both political and economic threats. Politically, hawkers served as a visible barometer of the government’s (in)effectiveness. As the new administration promised widespread reforms, ongoing issues—such as illegal hawking, poor hygiene practices, and the number of hawkers which reflected the economic health of the country—undermined the government’s credibility and legitimacy. Economically, illegal hawking diverted human capital away from more productive sectors. Every individual working as a hawker represented one less person who could be trained or upskilled, worsening the labour shortages the government faced in the 1970s.

To address the filigree of hawker-related issues, the PAP government developed and deployed four bureaucratic instruments in tandem:

1. Hawker-related legislation: New laws, including the Environmental Public Health Act (1969) and the Sale of Food Act (1973), established the legal framework for regulating hawker operations and enforcing public health standards.

2. Capacity-building of the Hawkers Department (HD): Since independence, significant resources were directed toward expanding the HD, culminating in a major reorganisation in 1972.[7] This transformation enhanced the department’s size and capabilities, enabling more effective enforcement of policies such as licensing and corrective measures, as well as long-term planning.

3. Hawker centres: Hawker centres were long-term hawker shelters[8] that imposed discipline (operational and spatial) and permanence to the hawker industry. To keep pace with hawker icensing, the HD accelerated construction efforts across the island, collaborating with various government and private agencies. Between 1974 and 1979, approximately 54 hawker centres were built.[9]

4. Hawker policies: New policies were carefully calibrated to manage the sensitivities of hawker enforcement while aligning with broader economic goals. Initiatives such as the One Hawker One License scheme helped redirect current and potential hawkers toward priority industries, while still preserving hawking as a viable livelihood for those who could not be upskilled.

Finally, in July 1973, the Ministry of the Environment launched a capstone initiative titled the “Extensive Hawker Control Programme,” aimed at licensing and regulating all illegal hawkers across Singapore. A total of 10,351 licenses were issued, with hawkers either relocated to newly built hawker centres near their original locations or to temporary pasar malams (night markets) pending the completion of newer hawker centres. By the end of 1973, the Ministry declared the programme a success, stating that “the task of bringing the unlicensed hawker situation in the Republic under control… [was] successfully accomplished."[10]

Hawking and its contemporary impacts

Following the Hawker Reform, the combined impact of policy, legislation, and infrastructure brought about a new praxis and experience of hawking.

Firstly, the reform contributed to the racial equalisation of the hawker trade and supported broader goals of racial integration. Implemented alongside flagship policies such as public housing and the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP), hawker centres became shared community spaces within racially curated neighbourhoods. Although hawker centres were ostensibly “neutral” infrastructure, their surrounding demographics influenced the food offerings to cater to diverse dining preferences and requirements (e.g., Indian, Halal options). Compared to the colonial period, when hawking was heavily dominated by Chinese and Indian communities, post-reform hawker centres helped shift the trade toward one that was more demographically representative of the nation.

Secondly, hawker centres continue to serve as instruments of both economic and social welfare by enabling access to affordable food. This is facilitated through indirect subsidies, particularly in the form of rent-controlled stalls, which encourage hawkers to pass on cost savings to consumers. Currently, rent constitutes only up to 12% of a hawker’s operating costs, whereas stalls in private coffee shops can command rents up to eight times higher.[11] This model has made it realistically affordable for Singaporeans to eat out regularly—a phenomenon uncommon in many developed countries.

Conclusion

This article has explored the rich and evolving history of Singapore’s hawking culture, one from streets to stalls. From its plausible pre-modern origins in the 14th century, to its entrenchment during the colonial era, and finally to the transformative Hawker Reform that cemented its role as an everyday culture, the story of hawkers is, in many ways, a microcosm of Singapore’s broader narrative. Ultimately, hawking culture stands as a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and ingenuity of its practitioners. As repositories of our culinary traditions, hawkers and hawker culture will continue to reflect our past, present and future identities, representing not only our roots but also a familiar sight in an ever-changing Singapore.

Notes

[2] Kueh, 103–5.

[3] Kueh, 43.

[4] Hawkers Inquiry Commission, ‘Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950’ (Colony of Singapore, 30 September 1950), 27, Reference Closed Collection (RCLOS), National Library of Singapore.

[5] Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 10.

[6] Kueh, From Streets To Stalls, 58.

[7] Kueh, 88.

[8] Hawker shelters are temporary shelters to organise hawkers (e.g., night markets), whereas hawker centres are long-term hawker shelters that are more permanent and intentionally planned

[9] Kueh, From Streets To Stalls, 97–98.

[10] Ministry of Environment/Hawkers Department (HD), ‘ANNUAL REPORT 1971 - 1973’, 1974, 32, National Library of Singapore, https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/government_records/record-details/0e86660b-115a-11e3-83d5 -0050568939ad.

[11] Kueh, From Streets To Stalls, 122.