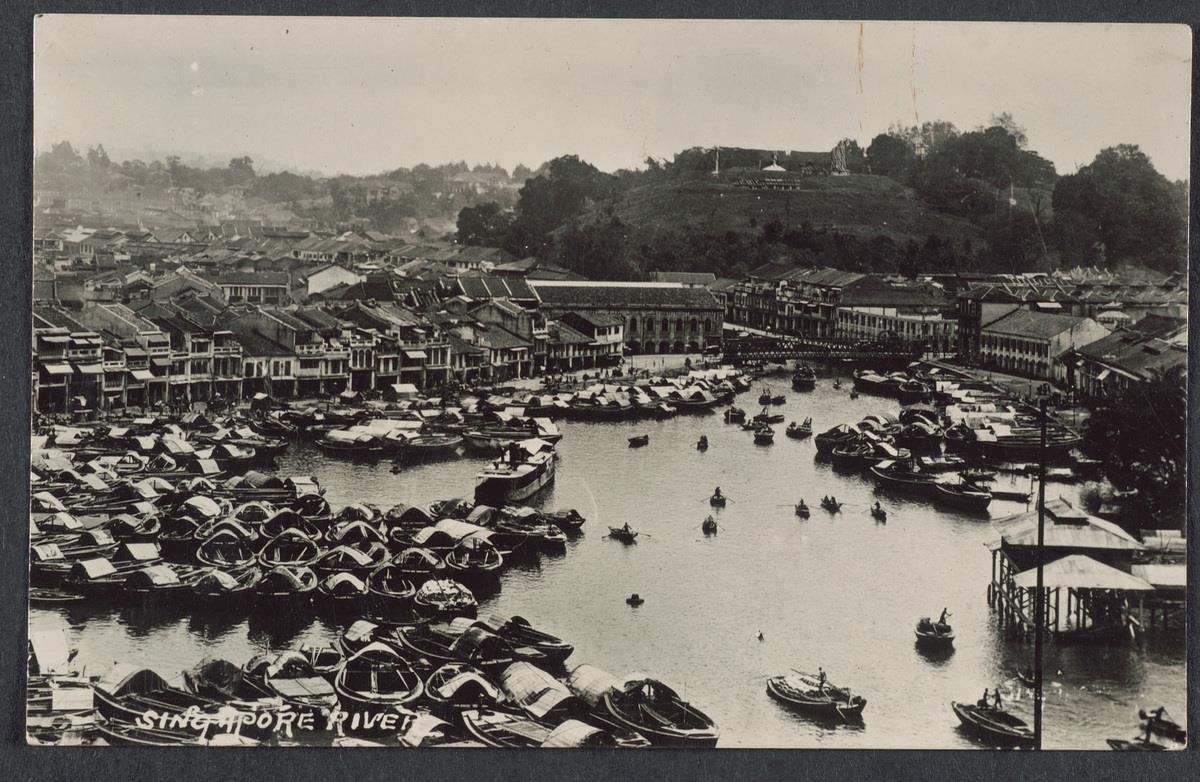

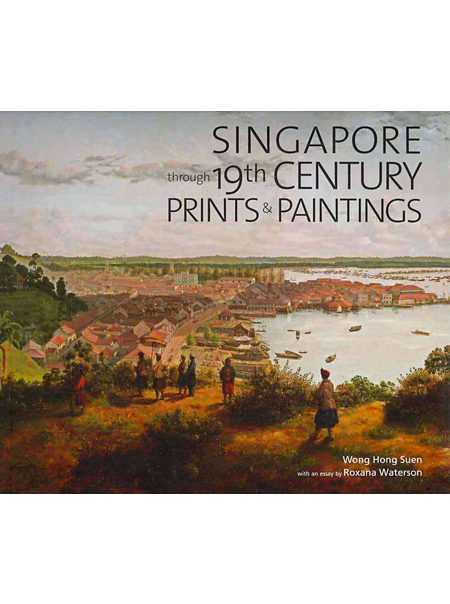

After Sir Stamford Raffles set up Singapore as a port, it quickly became a hotspot in the region. Trade took place in massive volumes, trade houses were built, and the culture of various communities started to take root here.

The increase in trade saw Singapore’s population grow more than ten-fold in just three years, exceeding the 10,000 mark by 1822. The migrant population had origins across Europe, China, South Asia, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. This surge in numbers, along with the mix of cultures on the island, led to land being used unsystematically, which strained the availability of space on the island.

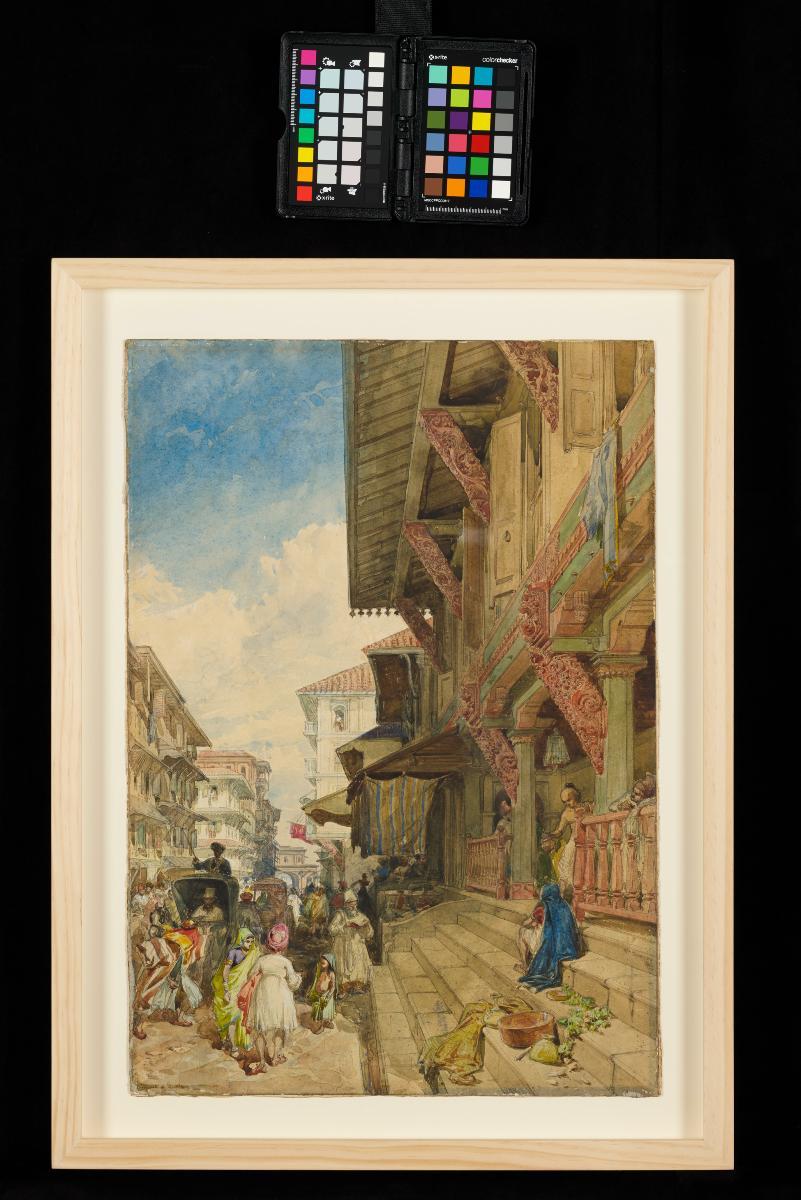

Singapore’s changing landscape

The Padang was a designated government area, but had houses and godowns erected on it because the Europeans and the Asian merchants preferred to set up their homes by the banks of the Singapore River. The colony, in short, was becoming disorderly and drastically different from Raffles’ original vision for the island.

Raffles was dissatisfied with Farquhar’s leadership and immediately set into motion plans to clean up the colony. In 1822, Raffles formed a Town Committee with the help of the colony’s engineer and land surveyor, Lieutenant Philip Jackson, to tackle the situation. From his personal observations of other colonial towns, such as Georgetown in Penang, he knew that a formal town plan had led to the successfully integration of Indian and Chinese immigrants. This was the solution he settled on, as it prevented groups from developing separately and creating haphazard settlements.

The Jackson Plan

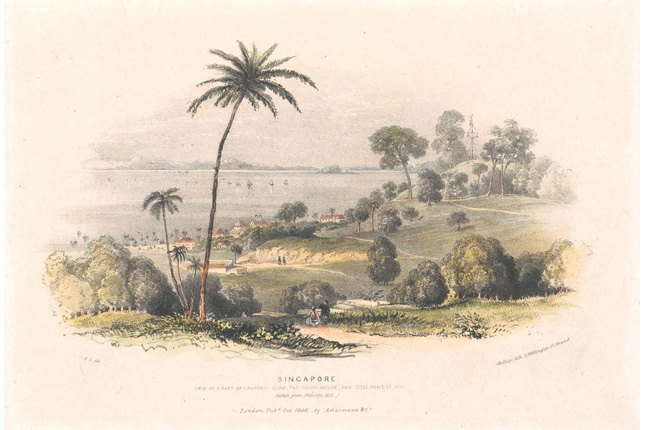

The town plan, titled “Plan of the Town of Singapore”, also known as the Jackson Plan, was published in 1828. It focused on the development of the area around the Singapore River, from Telok Ayer to the Kallang River.

Adopting features from colonial urban planning in British India, Raffles set up the seat of government in Fort Canning, similar to Calcutta’s fort-based layout. Raffles introduced ample greenery in the form of the Padang and the Botanic Gardens to give the impression of prosperity. It was also perhaps Singapore’s first step as a “Garden City”.

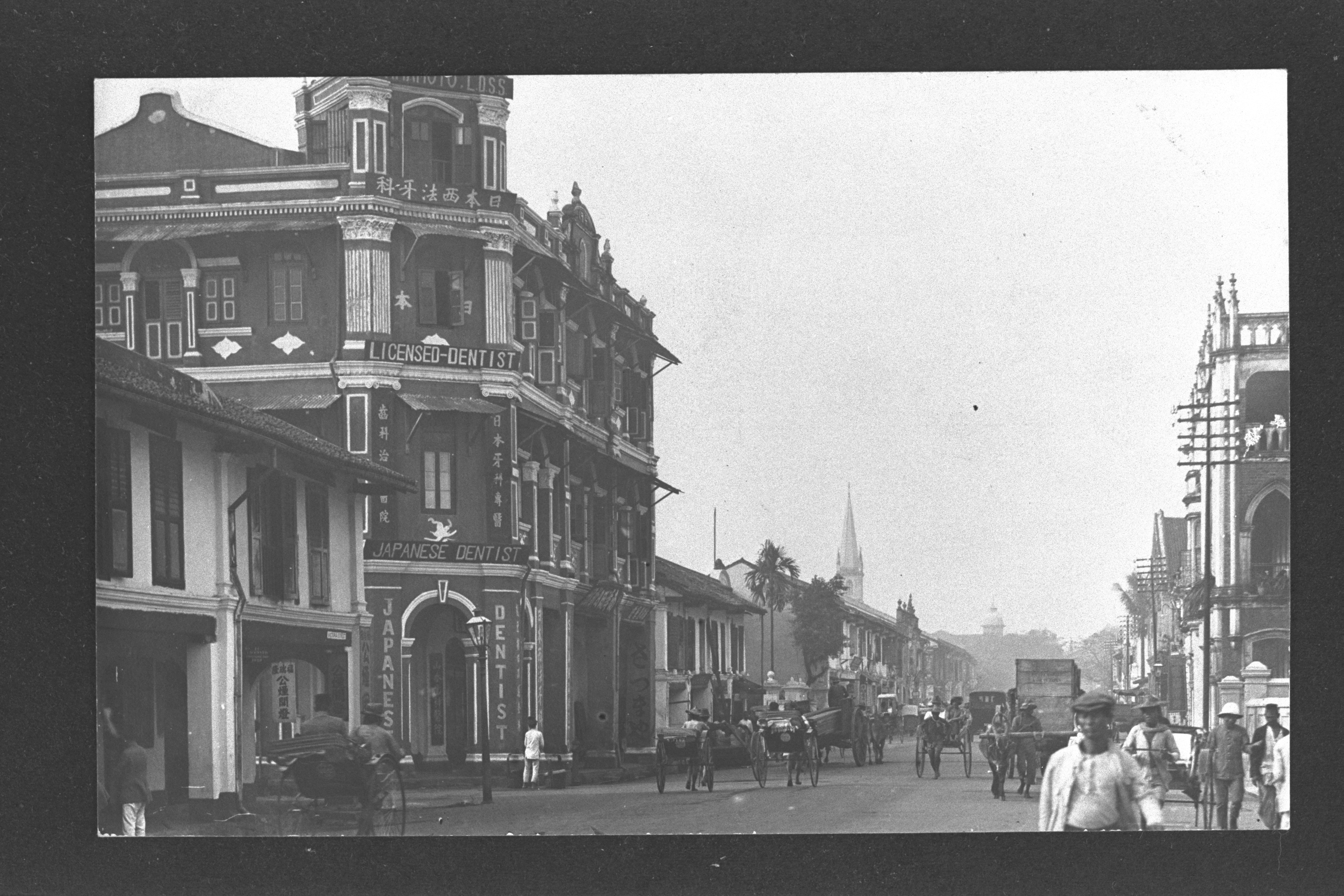

Guided by pragmatism, Raffles also introduced a variety of features through the town plan which are still visible on the Singaporean landscape today. He moved Telok Ayer Market to where it is today so that it would be in the centre of the commercial district. Meanwhile, burial grounds were pushed much further inland. He mandated continuous sheltered walkways – also known as five-foot ways – meant to protect pedestrians from the hot tropical sun and rain. He also ensured that buildings were constructed with masonry and roof tiles, to reduce fire outbreaks for accessibility and safety.

But perhaps his most impactful mandate was the push for uniform and regular streets. He was so precise that he called for right angle intersections, indicated a minimum width for pavements and a minimum spacing in between buildings. This gave Singapore its almost grid-like layout in the heart of the city today, as evidenced by the Jubilee Trail.

Impressive features and construction works aside, the plan was ultimately created to facilitate trading and promote communal harmony.

Every community would have a space to call its own.

The city was split according to residential, commercial or civic usage. There was also further segregation based on people’s provinces and the type of residency among citizens and merchants.

Land segregated for different communities

The Government was allocated the area stretching from Fort Canning to the Singapore River. The sea beyond the Padang (labelled “Open Square” on the Jackson Plan) was also reserved for Government use. However, some places like the Old Parliament House had to be acquired by the government as it was originally built as a private home, and some other European merchants had already built houses within this area.

The seafront east of the cantonment to the southwest bank of the Singapore River was largely reserved for Europeans. Its actual occupants were European traders, Eurasians and rich Asians. There were also spaces for merchants in the area. When combined with the south bank of the Singapore River, reserved for commercial use, this area makes up the modern day Downtown Core.

And as its name suggests, Chinese Campong (present-day Chinatown) was reserved for the Chinese, and they were allocated a large area southwest of the Singapore River. This was where Chinese laborers of different professions, such as samsui women, Chinese letter writers and wood carvers would reside.

Indians were allocated land further up north from the Chinese in a place called Chulia Campong, but they would find themselves moving to another point north of the river. It was at this spot where a booming cattle trade saw cattle pulling bullock carts across the streets. This is Little India today.

For the Malays, the plan focused on the area around the Sultan’s residence for Bugis and Arab migrants. The area was, and is still, known as Kampong Glam, and its development resulted in the creation of three distinct parts - an area for the Sultan, one for the Bugis settlers and another for the Arab merchants.

Sense of community

The legacy of the Jackson Plan can still be seen on our maps today through the representation of the different ethnicities and ethnic quarters of the island, in areas such as Chinatown and Little India. Singapore is no longer divided by ethnic enclaves. What we have today is the organic mixing of communities, by the people who decided to make Singapore their home.

But the Jackson Plan still represents the essence of Singapore – a cosmopolitan port city where people of different communities, ethnicities and religions come together to live, work and seek opportunities for a better life.