TL;DR

Singapore's skyline contrasts historic shophouses with modern skyscrapers. While international star architects now design iconic structures, early 20th-century buildings were primarily created by unknown Asian draftsmen, engineers, and craftsmen. Before 1926, there was no formal architecture profession in Singapore. A study of building plans from 1884 to 1926 reveals a diverse group of Asian designers who played a crucial role in shaping the city's architectural heritage. One notable Asian architect was Tan Seng Chong, who despite starting as an apprentice, became a prolific figure, submitting plans for numerous buildings, mostly commissioned by local Asian clients. This pioneering research aims to highlight the multicultural contributions to Singapore's urban development before the formalization of the architectural profession in 1926.

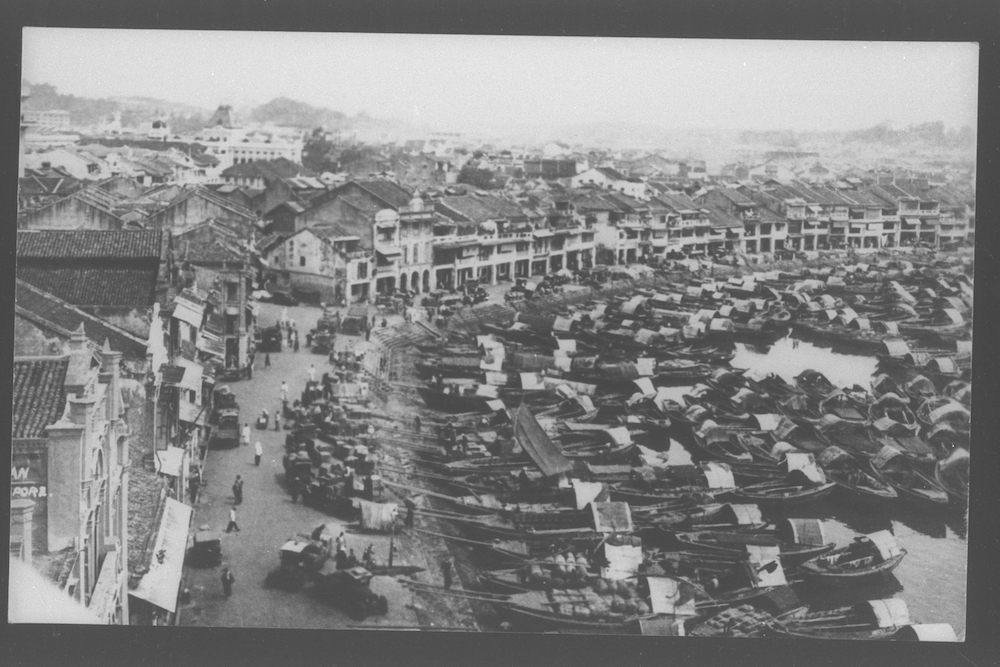

Singapore’s skyline is often depicted in postcards and tourist materials with an image that juxtaposes two to three-storey shophouses of early twentieth-century vintage against a backdrop of fifty-storey skyscrapers. The contrast signals the transformation that has taken place in the city over the past century as it transformed fromthird world to first and indicates how important the built environment is to the city history.

Shophouses and skyscrapers. Photo by John Teo

Architects were key agents in shaping the transformation of Singapore’s built environment and thus the creation of the city’s identity. Unlike the international star architects who now bid for and design the iconic buildings that define the city, the shophouses and other ‘vernacular’ architecture that symbolise old Singapore were largely created by an army of craftsmen, engineers, and laypeople who remain relatively unknown. Scholars have written about a handful of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century figures, mostly colonial officials like Stamford Raffles or Phillip Jackson who produced the first city plan in 1828 and British military engineers like William Farquhar and Edward Lake.

The shophouses, bungalows, factories, warehouses, mosques, and temples, that sprung up by the hundreds around the turn of the century, however, were not produced by European men alone. Instead, Asian and Eurasian residents drew up the plans for workers to construct. These men were not trained as architects or planners and often worked at the behest of colonial officials. In fact, before 1926 there was technically no profession called ‘architect’ in Singapore. It was only in 1926 that the government passed the Architects Ordinance. Interestingly, this ordinance was put into effect five years ahead of a similar one in the United Kingdom. Here you can see an excerpt from the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser with the announcement of the act. Before then, the people drawing up plans included civil engineers, surveyors, and technical assistants – draughtsmen and overseers.

As the city expanded and the demand for new buildings increased, these local men struck out on their own and were engaged by a wider variety of local clients, as well as by the European community. Early twentieth-century modernity in Singapore, and today architectural heritage was therefore shaped by a motley crew of Asian draftsmen, engineers, and others, rather than by a few pioneering European officials.

To find out more about these men, we studied building plans submitted to the colonial government’s Municipal Engineer between 1884 and 1926. These plans from the Building Control Division Collection are today kept at the National Archives of Singapore. The collection has around 246,000 plans from between 1884 and 1969. As one can imagine, analysing these plans was a labour-intensive and painstaking process. It would not have been possible without assistance from the National Heritage Board, through a grant entitled “Early Asian Building Designers in Singapore: Interrogating the Building Plans of Pre-1926 Singapore”.

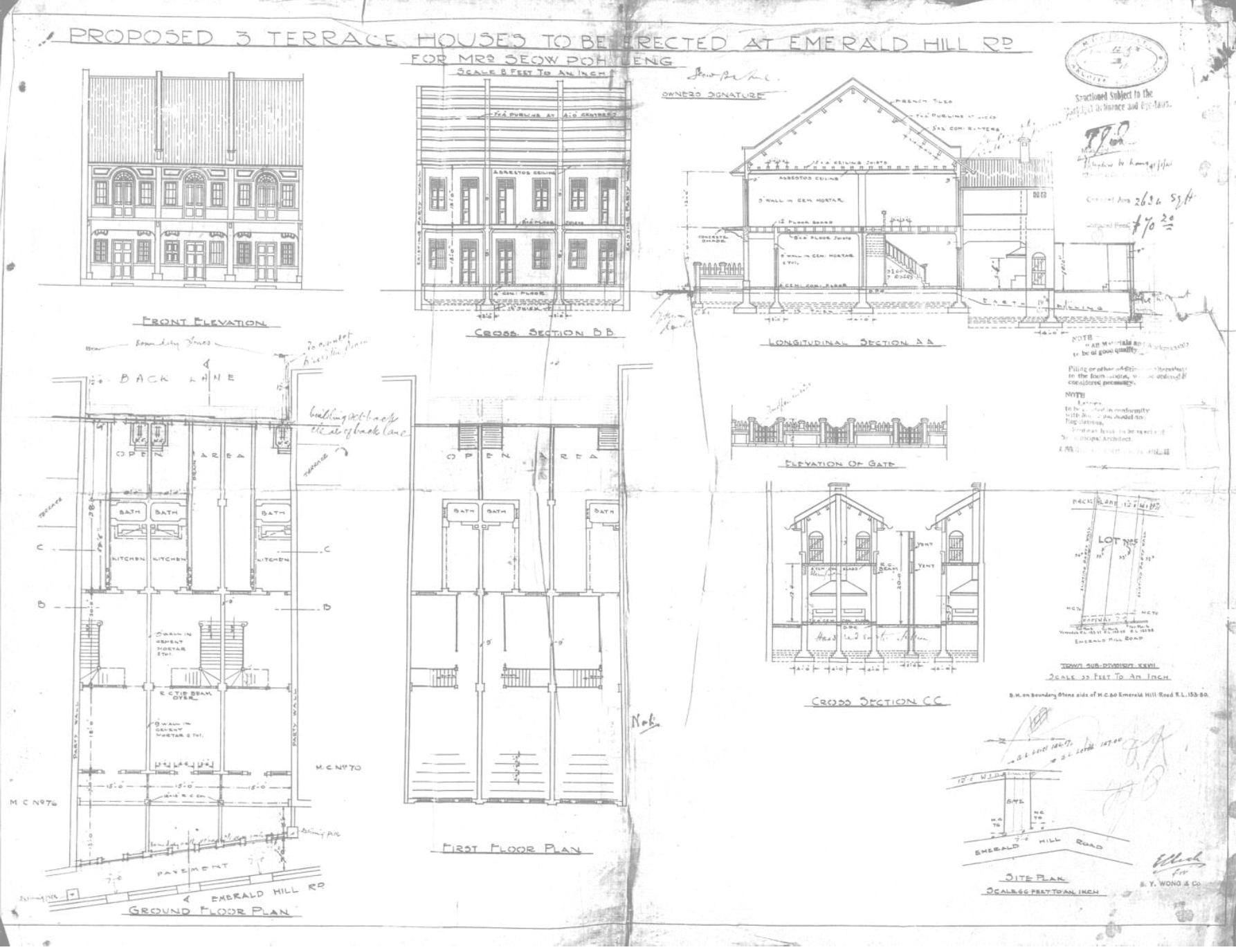

Proposed 3 Terrace Houses to be Erected at Emerald Hill Rd. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Here you can see an example of a building plan. Each was examined manually, noting the title, designer, client, typology, and building plan number. This plan includes the name of the plan and the client name (Proposed 3 Terrace Houses to be Erected at Emerald Hill Rd for Mrs Seow Poh Leng) at the top. You can also see the stamp in the top right corner with the plan number (Building Plan 15/1925). The plan number provided us with a unique identifier. The plan also tells us the type of structure, shophouse, and purpose, residential, in this case. At the bottom of the plan is the designer’s name (S Y Wong & Co). From this information, we created a database that allowed us to determine things like who was the most prolific, what types of buildings were most common, and what years there were relative increases or decreases in building plan submissions. The database we created contains information for over 21,400 sheets or plans like this one.

Family photograph of Seow Poh Leng, Mrs Polly Seow Poh Li (nee Tan), and their children Rosie Seow (later Mrs Lim Kok Ann) and Eugene Seow Eu Jin. Mrs Seow was the great granddaughter of Tan Tock Seng and the daughter of Tan Boo Liat. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

S. Y. Wong & Co. was the firm of Wong Siew Yuen, who was the fifth son of prominent businessman Wong Ah Fook, seen in this portrait c.1900. Singapore's early modernist architect, Alfred Wong, is related to Wong Siew Yuen, as his grandfather, Wong Siew Nam, was the eldest son of Wong Ah Fook. Collection of National Museum of Singapore. Gift of the Trustees of Wong Ah Fook’s Estate

At this point, a caveat needs to be made. Studying the Asian architects named in these plans is not straightforward. First, how does one identify someone as Asian? For our research, we defined an Asian as someone with origins in East, Southeast, or South Asia. To determine this, we looked at the surname of the designer in question. Of course, one cannot tell someone’s ethnicity or place of origin by their surname alone. But for the data found on the plans, this was the most sensible and practical indicator. Similarly, issues arose when trying to identify Eurasians. For the first stage of our analysis, we have left them out, partly because of the difficulty of differentiating Eurasians from European colonialists based on name alone. More detailed studies of individual designers will be our next step.

From our initial analysis of the plans, we have been able to glean a few preliminary insights. In terms of education, most of the people submitting plans received on-the-job training, informal pupillage, and later some form of a structured correspondence course and overseas formal architectural education. In addition, from the names gleaned by archival research, the Asian “designers” were more diverse than today, where approximately 93% of all registered architects are Chinese.[1]

As one might expect, the number of plans submitted generally followed economic trends influenced by world events, like World War I and the rubber boom in the early twentieth century. It makes sense, then, that pre-1926 designers were often commissioned by successful entrepreneurs like Tan Kah Kee and Eu Tong Sen, who channelled their financial resources into developing shophouses and other buildings.

One architect who was often hired was Tan Seng Chong. Tan began his career as an architect in 1899 as an “Apprentice Draftsman” working for the Municipality. In 1902, he was promoted to “Surveyor and Draftsman”. However, in what appears to be a restructuring of the Municipality, Tan was seemingly demoted back to “Assistant Surveyor and Draftsman”. By 1910, he had left his career at the Municipality and begun taking up private commissions as an architect. Our study shows that Tan was able to build up a decent reputation as an architect at this time and was easily able to find work when he left the Municipality. In 1912 and 1917, he submitted more than 150 plans for approval. Tan would continue to take building plan commissions until 1926, after which he would retire. In terms of sheer quantity, Tan Seng Chong stood out as a clear leader within Singapore’s early building scene.

Aside from being prolific, one other key fact that emerges from a study of Tan’s submitted building plans is that his clients were primarily Asian. Tan served a largely local clientele of small and medium-sized clients. These clients drove the expansion of the city and provided the demand for architectural services, which were then filled by an army of largely anonymous Asian draftsmen and engineers before the architectural profession was formalized in 1926.

The development of Singapore’s urban fabric was therefore driven by and large by local Asian investors, designers, and construction workers. By studying local architects and the architectural profession more generally, we hope our research will contribute towards the realisation of more multicultural and pluralist representations of national history.

This project was supported by the National Heritage Board's Heritage Research Grant.

Notes

- Register of Architects, Board of Architects Singapore. https://www.boa.gov.sg/find-architects/register-of-architects/ (accessed on January 2024).