Kavadi Making

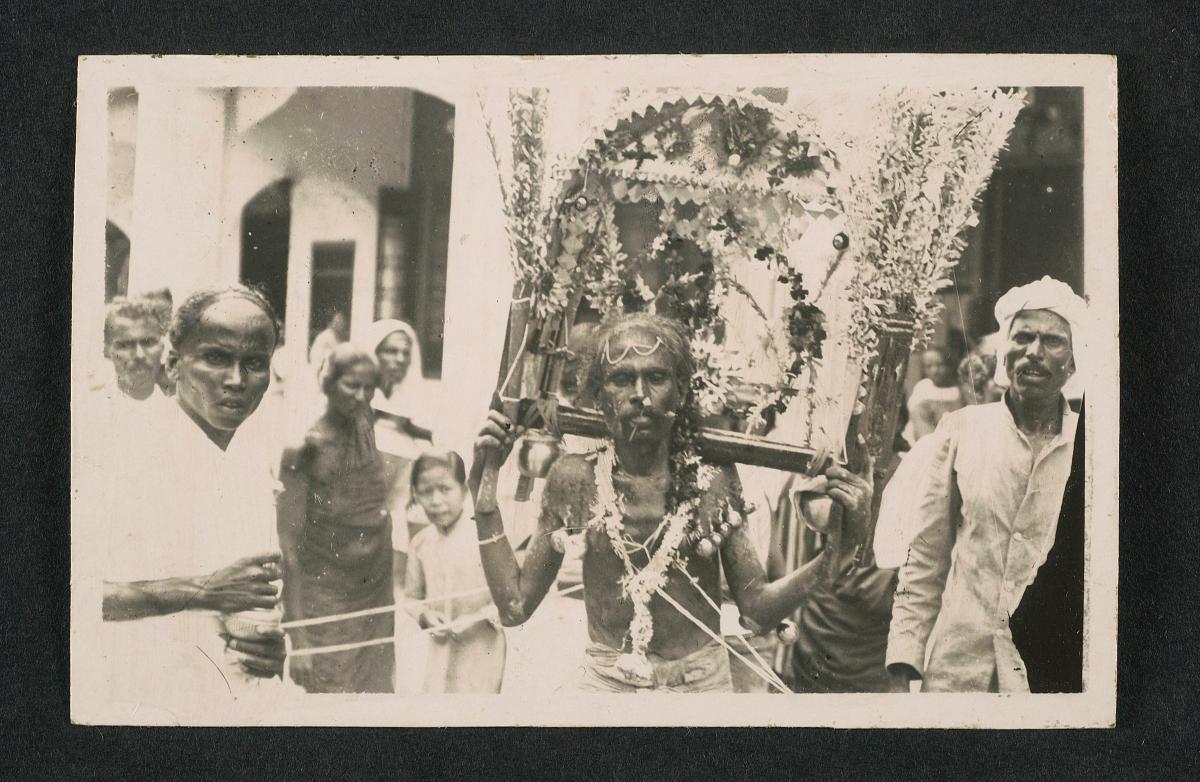

The Tamil term kavadi has been translated as a burden or load that is carried as a form of sacrifice to the Hindu god Lord Murugan. There are at least five different types of kavadi, including those that do and do not pierce the body. The simplest kavadi consists of a short wooden pole surmounted by a wooden arch, and pictures or statues of Lord Murugan or other deities are fixed onto the arch. The kavadi can also be decorated with peacock feathers or a small pot of milk attached to each end of the pole.

In Singapore, kavadis are carried during Thaipusam and Panguni Uthiram. The former occurs in the Tamil month of Thai while the latter occurs in the Tamil month of Panguni during the full-moon day. Both occasions are celebrated by Hindu Tamil devotees of Lord Murugan, as opportunities to seek blessings, make vows, and offer their thanks when those vows are fulfilled by their deity.

Local practitioners have shared that kavadis used to be made completely by hand by local craftsmen in Singapore. Over time, it has become more economical to outsource parts of the production process to artisans in India. Thus, making a kavadi today involves a transnational network, whereby the designs originate in Singapore, parts are ordered from India and the kavadi is assembled in Singapore for use here.

Geographic Location

The practice of making and carrying kavadis can be traced back to India, from where migrants have taken it to different parts of the world. In places with diasporic communities such as in Singapore and Malaysia, the Indian communities also practice carrying body-piercing kavadis.

Communities Involved

The number of kavadi makers in Singapore is relatively low. They are likely to be Tamil men, as women are not typically involved in this line of work.

Kavadi makers often share a close consultative relationship with the kavadi carriers, to produce personalised kavadis that suit the requirement of specific carriers. On festival days, the craftsman may even be present to help the carrier assemble the kavadi and wear it.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Skilled kavadi makers have knowledge of the different types of kavadi, ranging from the simple paal kavadi — which consists of a wooden pole with a pot of milk attached at each end and the ends of the pole decorated with a semi-circular design — to the more complex metal kavadi with spikes to pierce the carrier’s body.

To make the latter, a craftsman starts with a metal sheet, preferably aluminium since it is light enough for a person to carry the kavadi for six to seven hours. Sometimes, gold-plated and brass-plated aluminium sheets are used. Holes are punched into the metal to allow rods, spikes, pots, peacock feathers, and other ritual artefacts to be attached. The shape of the plate and the spacing between the holes are dictated by the design of the kavadi. Metal embossing is a recent trend in kavadi making. This creates raised or sunken designs on the metal sheet and is usually done by artisans in India.

A devotee typically reuses his kavadi, sometimes for as long as 20 years. So, a new kavadi need not be made for him every year. After a festival, the kavadi is disassembled and stored till it is time to be used again.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Balakrishnan s/o Sadasivam learnt to make his first kavadi when he was 19 years old. Completing that project took him a year. He did most of the work in the evenings and on weekends, doing everything by hand, including measuring, cutting, altering, polishing, and grinding.

Though he started with rudimentary kavadi designs, his designs have evolved over time and become more elaborate. He has even invented a new technique for fastening spikes to a kavadi, by which threads are cut into the ends of the spikes so that they can be screwed securely into the structure. He adapted this method from the threading found in bicycle spokes. Since he believes that the making of kavadi is a religious undertaking and not a business, he has had no qualms in sharing this idea with others.

Mr Balakrishnan still makes kavadi for others, together with his son, godsons, and friends. He hopes that working together will help pass on his knowledge of the craft. Since parts of a kavadi are procured from India these days, he has also helped his family and friends connect with artisans there. When these parts arrive from India, the group assembles them into a complete kavadi.

Present Status

There are very few craftsmen in Singapore who are involved in making kavadis by hand. Mr Balakrishnan thinks that this is because young people simply do not have the time to build a kavadi from scratch. Another craftsman, Mr Moti Lal Prasad, has also pointed to economic reasons. Each customised kavadi can take three months to complete. With five to six orders a year, he says that one cannot make a living by doing this full time in Singapore.

Tying up with craftsmen in India to produce parts of a kavadi has cut some of the hard labour and costs. This has allowed the remaining kavadi makers in Singapore to carry on their practice and continue honing their craft.

References

Reference No.: ICH-066

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Bhattacharya, Jayati. And Kripalani, Coonoor. Indian and Chinese Immigrant Communities: Comparative Perspectives. London: Anthem Press, 2015.

Ho, Pamela. “Carrying the craft”, Singapore Essential Arts and Culture Guide. Singapore: National Arts Council, 28 January 2018.

Mathew Mathews. The Singapore Ethnic Mosaic: Many Cultures, One People. Singapore: World Scientific, 2017.

Sandhu, K.S and Mani, A. Indian Communities in Southeast Asia. Singapore: ISEAS, 2006.