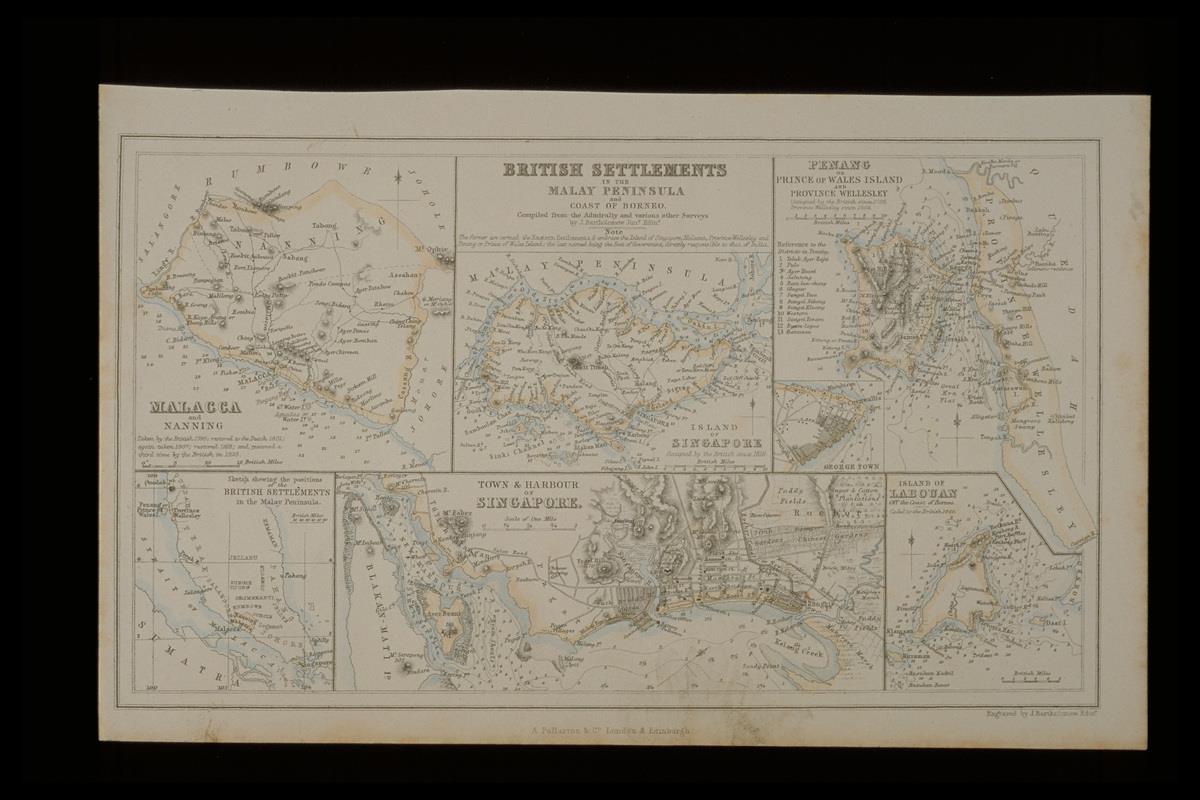

With great geographical benefits come great strife, as the power struggles between the 14th to the 17th centuries prove. The late 14th century saw Singapore being attacked. This compelled the Sultan to flee to Malacca, where he founded the Sultanate of Malacca, which Singapore became a part of. In 1511, Malacca fell to the Portuguese – the dominant European power in the region at the time – forcing its Sultan to retreat back south, where he established the Johor Sultanate. Singapore then fell under the rule of this Sultanate. In 1613, the Portuguese raided and burned the island to the ground, and for the next two centuries, Singapore faded into obscurity while still being nominally a part of the Johor Sultanate, eventually falling under regional Dutch control after the Dutch established a monopoly over trade within the archipelago.

When Sir Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore with Major-General William Farquhar in January 1819, there were only about 1,000 inhabitants on the island, and they were greeted by a quiet that belied its eventful past. However, this did not stop Raffles from seeing Singapore’s potential – after all, he had heard so much about the place from his studies, and correspondence with Farquhar.

Sir Stamford Raffles

Fluent in Malay and having served as assistant secretary to the Governor of Penang at the age of 23, Raffles was familiar with the region’s history and culture, and eventually served as the Lieutenant-Governor of Java. He had also written a book, The History of Java. All this knowledge and understanding led him to strongly believe in the importance of breaking the Dutch monopoly of trade in the region.

As the Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen, Raffles sailed to Penang after gaining permission to secure a post for the British East India Company, on the condition that he would not antagonise the Dutch, especially with the rising Anglo-Dutch tensions against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. However, Raffles was met with a lack of cooperation by the Governor of Penang, and he also learned that the Dutch were claiming all territories under the Johor Sultanate. But there was still a chance to claim Singapore, since they had not yet occupied the island.

Despite receiving instructions from his immediate supervisor – the Governor of Penang – to abandon his quest and await further orders, Raffles slipped onboard the Indiana to reunite with Farquhar, and they arrived in Singapore on 28th January 1819.

The events that followed took place in quick succession – everything happened within ten days.

The succession dispute between Abdul Rahman and Hussein Shah

Upon their arrival, they found that Temenggong Abdul Rahman, the Governor of the Johor-Lingga-Riau Sultanate, was Head of the island. On 30th January 1819, the British and Temenggong Abdul Rahman came to a provisional agreement for the British to establish a trading post on the island. However, the area was under the charge of the Dutch and Bugis, who would never agree to a British base in Singapore. To prevent the Dutch from challenging the legality of this treaty, Raffles needed the endorsement of the Malay sovereign.

The reigning Sultan at the time was Tengku Abdul Rahman. Tengku Abdul Rahman was the second born son, and his older half-brother, Tengku Hussein Shah, should have been the rightful successor. However, Tengku Hussein Shah was away at Pahang at the time of the Sultan’s passing in 1811, which led to his younger half-brother, Tengku Abdul Rahman, becoming Sultan instead.

The hasty coronation ceremony to instate Tengku Abdul Rahman as Sultan before Tengku Hussein Shah’s return was organised with a politically-charged agenda by the leader of the Bugis faction, effectively aligning themselves with the Dutch. Tengku Hussein Shah remained in Pahang, clueless to these developments. He eventually found out, but with the Bugis faction now allies with the Dutch, and after being warned by the British in Malacca not to interfere in Riau-Lingga affairs, Tengku Hussein Shah and his supporters dropped all plans to challenge Sultan Abdul Rahman for the throne. Sultan Abdul Rahman was pressured to remain the Sultan despite his lack of interest and Tengku Hussein Shah went into exile in Riau.

Using the dispute

Aware of this dispute, Raffles struck a deal with Tengku Hussein Shah, knowing that this man had the support of the Malay chiefs in Riau and Pahang. It was a calculated move on his part, since Abdul Rahman was crowned by the Bugis faction that allied themselves with the Dutch, and this may have presented challenges in the negotiations for a British trading settlement in the region.

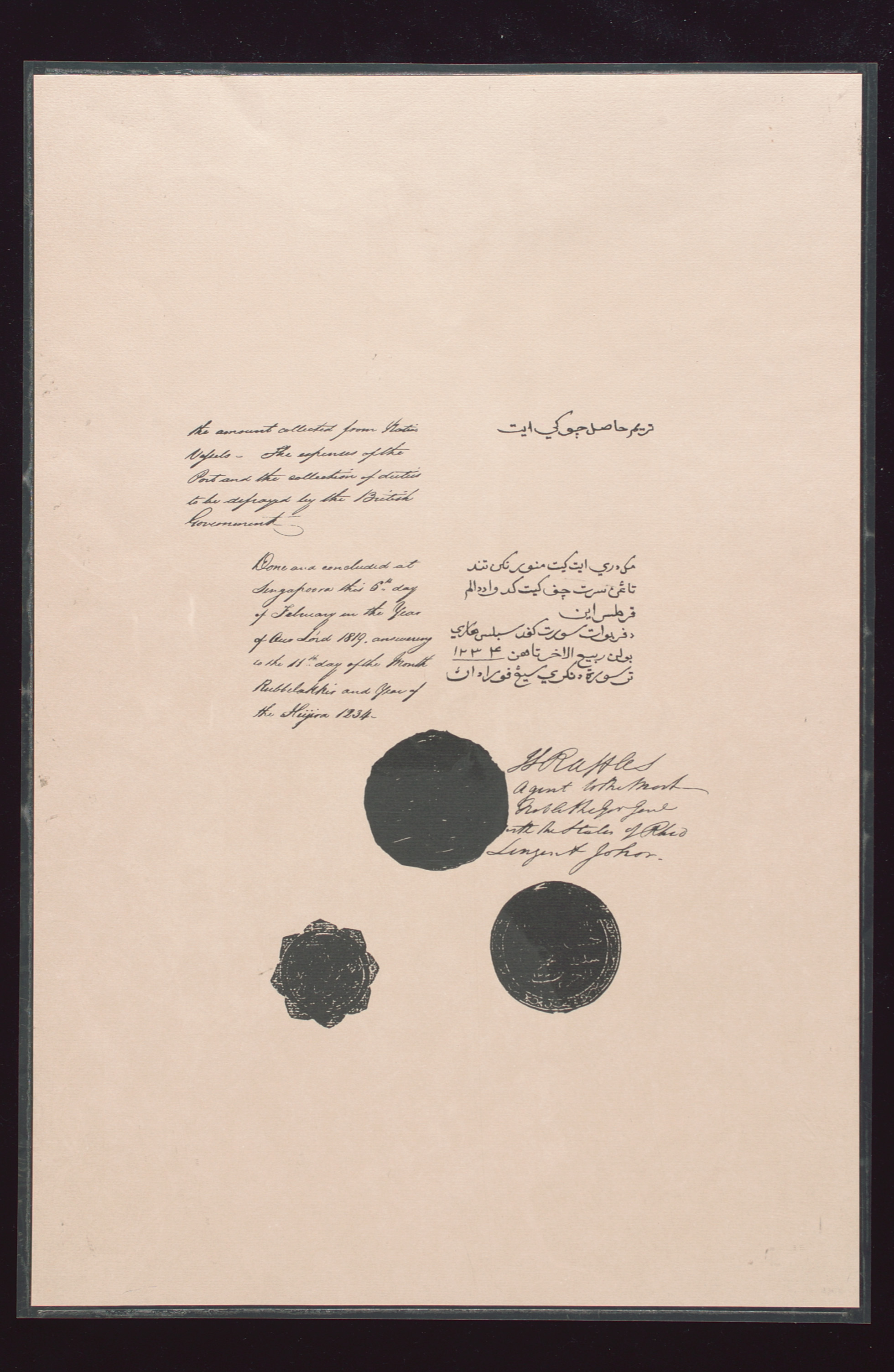

Raffles summoned Tengku Hussein Shah to Singapore, acknowledged him as the legitimate successor to the throne, and proclaimed him the Sultan of Johor. An official treaty was signed on 6th February 1819 with Temenggong Abdul Rahman and Sultan Hussein Shah, which gave the British East India Company the right to operate a trading post in Singapore. This acknowledgement was beneficial for both the Temenggong and Sultan Hussein Shah. Both men were paid a handsome sum of money yearly to uphold this agreement.

Raffles left Singapore the next day and he instructed Farquhar to take care of this new settlement as its Resident and Commandant.

The Dutch strike back

Though the events leading up to the 1819 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance were tumultuous, they paled in comparison to the commotion caused once the Dutch in Batavia got wind of this new British development. The Dutch went on to challenge the legality of the settlement, stating that the island had always been within their sphere of influence. However, the British stood their ground as they had begun to recognise Singapore’s strategic value

As predicted, Singapore grew from a trading port to a trading settlement in the span of four months. Singapore became a regional gem – attracting traders, merchants and pioneers from all over.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty

Though it took years for the Dutch and the British to see eye to eye, Singapore’s legal ambiguity was resolved in 1824 with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty. This treaty recognised British influence over Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. It also officially acknowledged Dutch authority to the south of Singapore and in the Indonesian archipelago.It can be argued that this resolution came about due in part to Raffles – his act of acquiring Singapore took tensions to an all-time high and forced the relevant authorities to come to an agreement.

There would be other Anglo-Dutch treaties to come in the 1870s but for now, this chapter was closed.

Eventful and fast-paced, Sir Stamford Raffles played a key role in this significant turning point in Singapore’s history, though some of his methods could be viewed as questionable.