Text by Hong Wei En Isaac, Goh Seng Chuan Joshua, Lim Wen Jun Gabriel and Gavin Leong

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

Enter the term "Yishun" into any online search engine and questions such as "How scary is Yishun?" and "Is Yishun jinxed?" are likely to appear. This reflects, perhaps the broader public fascination with Yishun in recent years from 2018, which stems in part from apocryphal accounts of unusual occurrences in the town. The Straits Times, for example, has reported a disproportionate number of cat killings in Yishun, in addition to a purportedly high rate of murders and suicides. There was even an incident in January 2017 in which two men attempted to use a stun gun on police officers – an act hitherto unheard of in Singapore. Coupled with other sensational happenings both reported and rumoured, it is perhaps not surprising that Yishun's identity has of late been defined by this tendency for the unusual to occur.

Set aside such reports, however, and Yishun is not unlike other suburban towns in Singapore which trace their histories to small-scale villages in the rural periphery. Its toponym, a pinyinised variant of Nee Soon, reflects this. The latter was the place-name of an eponymous village formerly located at the intersection of Thomson Road and Sembawang Road. Until the 1980s, Nee Soon Village was home to a post office, a community centre and a market, but these were subsequently relocated when villagers were gravitating towards Yishun New Town following its construction later in the same decade.1

A kampong house in Nee Soon Village, 1985

A kampong house in Nee Soon Village, 1985

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Given this seemingly anodyne history, how then did Yishun gain its reputation as a place for the odd and unexpected? Is this an accurate reflection of Yishun's heritage and identity? Taking such musings as an inspiration, this articles examines Yishun's broader history, which reveals that in some respects, the impression of Yishun as a place where the unusual unfolds may have roots beyond today's urban myth. Even so, we suggest that this is but one facet of Yishun's heritage. From tranquil Yishun Park to the quaint but alluring Sembawang Hot Spring, Yishun is equally defined by its pleasant environs which meld aspects of today's fast-paced life with the less hurried ambience of yesteryear. In this respect, Yishun shares much in common with mature heartland towns such as Hougang, where one can detect elements of an old-world charm sandwiched amidst more recent urban developments. Arguably, one could thus posit that Yishun's place identity is defined not by a singular element, but by its synthesis of the odd and the ordinary, the new and the old, and the modern and the rustic.

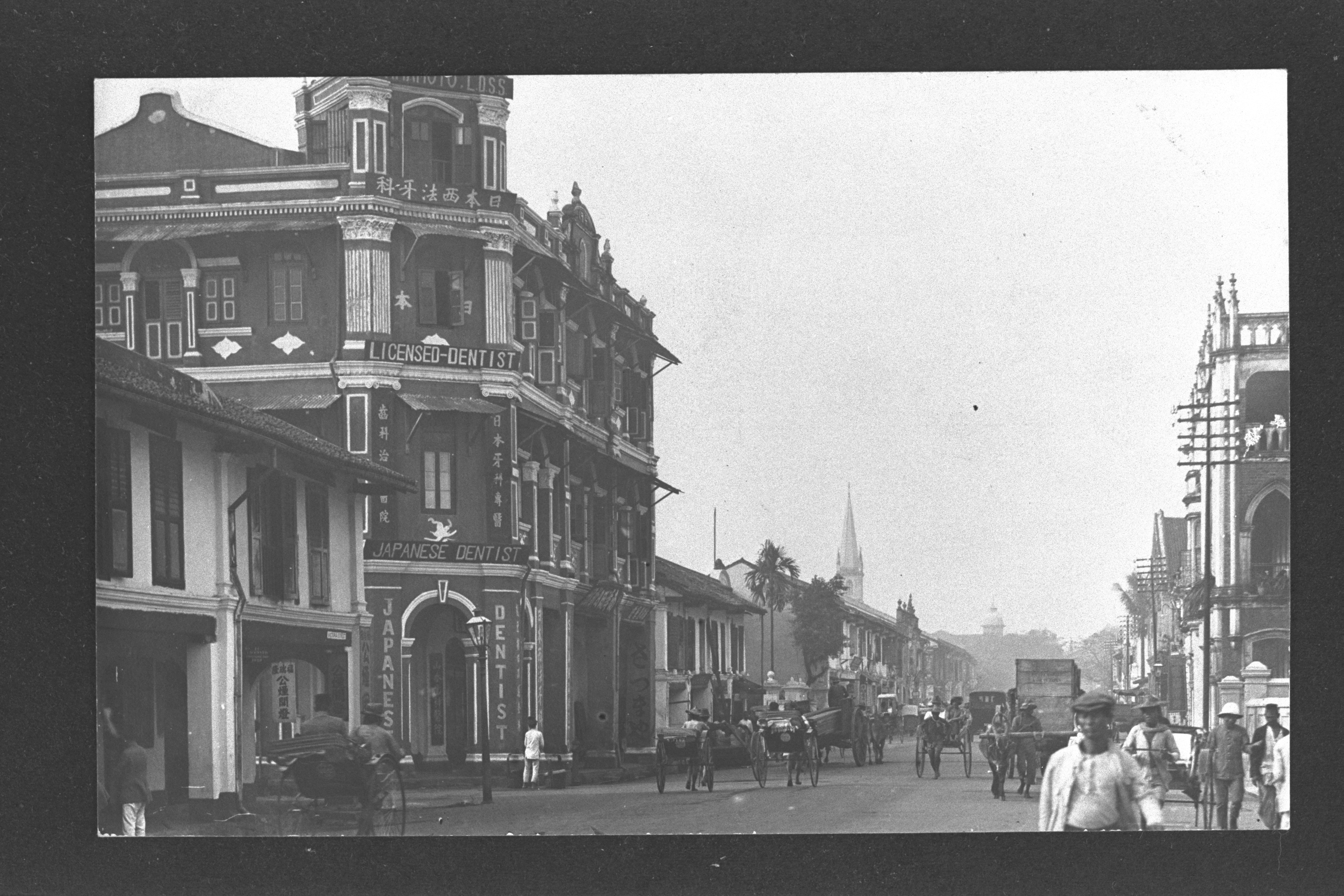

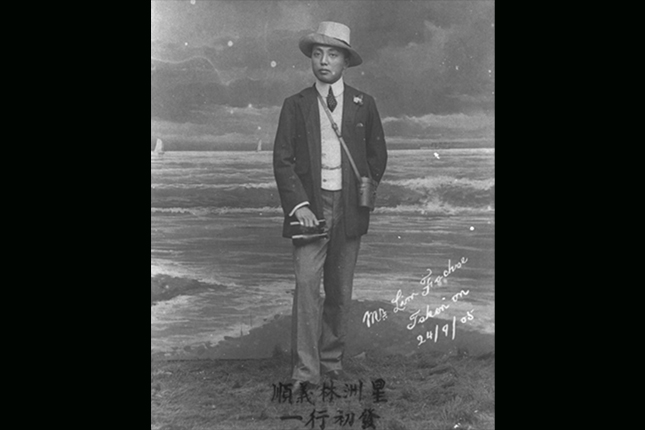

The history of Yishun's association with the odd and unusual can be traced to the late-1880s, when the area near today's Lower Seletar Reservoir Park was dominated by gambier and pepper plantations.2 This was a period of shifting economic fortunes as the value of both crops had begun to fall. In their place were rubber plantations that started sprouting up across Singapore during the late-19th century.3 Yishun, however, proved to be one area in Singapore where the iconic rubber plant was rivalled in prominence by a zesty and quirky tropical fruit – the pineapple.4 More than just an exotic crop, pineapples were prized by the British as a tangible expression of the wealth and fecundity of their tropical imperial possessions.5 This in turn explains why prominent businessmen of the era soon sought cost-effective ways of planting the spiky fruit.6 While some assert that growing pineapple amongst slow-growing rubber trees was a technique pioneered by rubber magnate Tan Kah Kee, it was Tan's contemporary, Lim Nee Soon, also known as the Pineapple King, who popularised it.7 In fact, by the 1910s, some 6,000 acres of land in today's Yishun and Sembawang had been leased to Lim's London-registered Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company for the growing of both crops.8 Eclipsing smaller estates such as the York and Kan Hoe estates, Lim's extensive plantation holdings were testament to his strong association with the area. By 1930, the British even saw fit to rechristen Jia Chui Village to "Nee Soon", after Lim himself.9

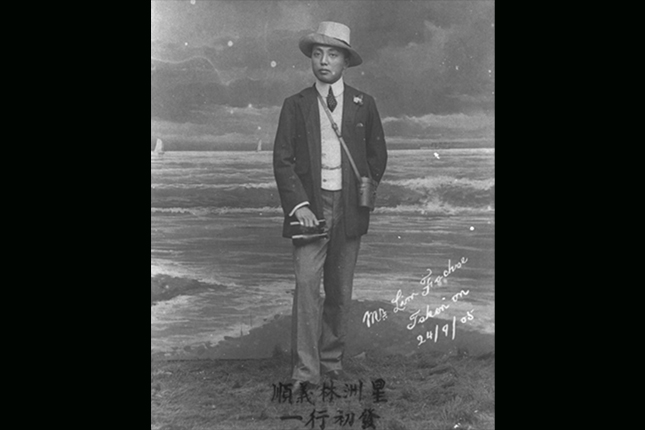

A photograph of Lim Nee Soon, 1905

A photograph of Lim Nee Soon, 1905

Lim Chong Hsien Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Lim Nee Soon in front of a truck fully loaded with pineapples, 1916

Lim Nee Soon in front of a truck fully loaded with pineapples, 1916

Lim Chong Hsien Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Initially populated by plantation workers toiling in adjacent estates, Nee Soon Village had, by the 1920s, emerged as a small but notable centre of commerce in the northern part of Singapore.10 Interestingly, not unlike the urban myths surrounding Yishun today, the village also attracted significant press attention for a string of unusual occurrences. As early as 1923, The Straits Times reported the arrest of a "Hylam" (colloquial term for a person of Hainanese descent) named Wee Teck at Lim Nee Soon's rubber factory for the unlicensed possession of an automatic pistol, 96 rounds of ammunition and a knife.11 While such infractions of the law may no doubt have been commonplace, what was intriguing was the fact that the accused was arrested in his sleep at the unearthly hour of 4am, with a loaded revolver stashed under his pillow.12 Another odd occurrence was a 1932 fire strong enough to demolish one of the buildings owned by Lee Rubber Co. Ltd. Interestingly, the 300 piculs of rubber contained within it remained largely untouched.13

Lim Nee Soon Rubber Factory, 1985

Lim Nee Soon Rubber Factory, 1985

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Such events aside, other uncanny incidents in Nee Soon were associated with the significant British military presence in the area. This generated its own set of tensions. For example, in the early days following the end of the Second World War, an ammunition explosion at Nee Soon Camp, a military base, was reported to have "broke[n] windows in Nee Soon Village, after having initially been set off by a grass fire".14 As if this was not disconcerting enough, two men were found mysteriously shot dead at the same camp later the same year.15 Yet even such reports could not compare with the bizarre sightings of apparitions which habitually thrust Nee Soon into the national limelight. Indeed, in 1949, Nee Soon Village was said to be abuzz with sightings of a woman who "had returned from her grave and had gone back to her husband".16 This association with the supernatural seems to have continued, for a New Nation report some three decades later mentions two wardens stationed at Seletar Reservoir who testified to having "heard and see weird things in the [Nee Soon] vicinity.17 Quoting a local bomoh (Malay for "spirit hunter"), the newspaper speculated that Nee Soon was indeed home to a spirit, which likely inhabited an area "where a lot of accidents have occurred".18

Beyond the supernatural and mysterious, another facet of Yishun's reputation as a place for the unusual involves the equally fascinating fact that the town has throughout its history play host to unique events not otherwise found in Singapore. Among the most notable was the earliest iterations of the Singapore Grand Prix, which ran from 1961 to 1973.19

Taking place along a 4.8km circuit that wound from Sembawang Hill Circus through Old Thomson Road, the route took drivers to the junction of Mandai and Nee Soon Roads, within a whisker's breadth of Nee Soon Village.20 In fact, so proximal was Nee Soon to the race route that both Nee Soon Police Station and Nee Soon Village were designated as alighting points for guests arriving by bus.21 In the words of a Straits Times reporter covering the even in 1961: "the crowds streamed in all day through the two main gates at Sembawang Circus and Nee Soon", such that "police [soon] had to stop the sale of tickets at both entrances".22

Apart from significant events such as the Grand Prix, one can also note the phenomenon of institutions in Yishun adopting rather unique practices which speak to the peculiarities of their geo-historical situations. A fine example would be Naval Base Secondary School, which in the 1950s was the only secondary school in the Sembawang-Yishun area. As it was located within the British Naval Base, staff and students had to adopt the unique convention of having all 10 fingers printed before being issued entry passes! Another site which similarly speaks to the somewhat quirky reputation of Yishun is Sembawang Hot Spring, whose waters some believe can cure rheumatism and skin diseases.23 Initially discovered by W. A. B. Goodall in 1908, the spring has over the years played host to institutions such as Fraser and Neave, the Japanese Military and even the Singapore Government, who explored plans for bottling plants, thermal baths and a spa complex!24 In 2017, the National Parks Board announced that the spring would be transformed into a park 10 times its current size by 2019, featuring a café and a floral walk.

Sembawang Hot Springs, 2010

Sembawang Hot Springs, 2010

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board

Yet even if one takes into account Yishun's propensity to play host to the odd and unusual, what else can be said to be constitutive of the town's identity and heritage? As estimated earlier, it would be remiss only to allude to the odd and uncanny, while omitting to mention how one can find in Yishun pockets of a rustic, laidback environment interspersed amidst the high-rise concrete jungle. Yishun Park, a 17-hectare green lung situated in the heart of Yishun New Town is an example of such a space.25 While parks are certainly an ubiquitous element of Singapore's landscape, Yishun Park is distinctive in the fact that it serves, quite literally, as a material embodiment of Yishun's very own history. Indeed, unbeknownst to many, the park is sited on the grounds of the former Chye Kay Village, and this is evinced by the numerous rubber, rambutan, durian and guava trees which continue to flourish today.26

Yishun Park, 2018

Yishun Park, 2018

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board

Leaving the verdant for the azure, it is also worth pointing out that Yishun has the distinction of being home to not one but two equally idyllic reservoir parks – Upper Seletar and Lower Seletar. Coupled with the little-known fact that nearby Sungei Khatib Bongsu is home to one of Singapore's few remaining patches of tidal mangrove forests, it is easy to see why some see Yishun as Singapore's rustic northern frontier, replete with sites of natural beauty.27

Lower Seletar Reservoir, c. 1980

Lower Seletar Reservoir, c. 1980

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

If nature is central to Yishun's laidback, old-world charm, so too are its many long-time family-run businesses nestled amidst the bustle of modern Yishun. Located along Sembawang Road, Chong Pang Nasi Lemak is one such outfit. Tracing its roots to a stall set up at the former Chong Pang Village Hawker Centre in 1973, this popular food outlet has since become so closely associated with the area that food bloggers have christened its rendition of the well-known rice dish the "pride of Chong Pang". The stall takes its name from the eponymous village, which itself was named after the son of Lim Nee Soon – Lim Chong Pang.

Today, Chong Pang Nasi Lemak serves as a reminder of the old village's former shops, which included traditional bakeries, tailors and even a village acupuncturist.28 Indeed, from a long-term perspective it would not be unreasonable to suggest that the stall plays a contemporary role mirroring that of the former Sultan Theatre, which, according to Pearl Sequerah, was the historical landmark of Chong Pang Village during its heyday in the 1950s.29

Chong Pang Nasi Lemak, 2018

Chong Pang Nasi Lemak, 2018

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board

Chong Pang Village, 1986

Chong Pang Village, 1986

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Chong Pang Market and Food Centre, 2018

Chong Pang Market and Food Centre, 2018

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board

Until its recent relocation to Owen Road, another enterprise which was synonymous with Yishun was Danny's Tattoo Art (known colloquially as the Gurkha Store) – located in a row of shophouses along Transit Road. According to its proprietors, Madan Lal Aitabir and Ram Lal Aitabir, tattoos were previously priced from between $6 to $15, which in the 1970s, attracted the attention of military servicemen from Britain, New Zealand, Australia and the United States who inhabited the nearby Nee Soon military barracks. Some American soldiers returning from the Vietnam War were even known to have requested tattoos inscribed with names of their fallen comrades. Other servicemen serving in the Nee Soon Camp from the 1980s onwards may also have been familiar with Chua Peng Hock Trading Co., better known by its later iconic name, Hock Gift Shop. Established initially as a small-scale setup selling "tidbits, cold drinks, plastic bags, and army field camp products", it later began offering army personnel a variety of bespoke services including embroidery and the embossment of name tags. With the variety of paraphernalia sold, it is perhaps not surprising that a 1981 New Nation report saw fit to describe Transit Road as the "Change Alley of Nee Soon Village" – "two dozen little ships in a remote part of Singapore".30 Somewhat ironically, it is change which has since caught up with Transit Road. Once a hub for National Servicemen undergoing their Basic Military Training, the row of shophouses has in recent years been replaced by a private residential development.

The change that has recently enveloped Transit Road can be seen as emblematic of wider developments that have occurred in Yishun since the 1970s. With the construction of Yishun Town proceeding apace from 1977, much of the landscape has become dominated by high-rise Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats, punctuated by the occasional neighbourhood centre.31

An aerial view of Yishun Town when it was under construction, 1983

An aerial view of Yishun Town when it was under construction, 1983

Image courtesy of the Housing & Development Board

The commercial heart of Yishun has shifted too, from the area around the former Nee Soon Village to Yishun Central, home to the gargantuan Northpoint City. Yet, as examined, elements of a rustic, laidback Yishun still exist, lending the town an idyllic and tranquil vibe typical of towns built in the 1970s and 80s. Although this image of Yishun's identity as a pleasant and laidback town has in recent years been overshadowed by sensational reports of it purportedly peculiar character, it is perhaps the synthesis of both of these facets – the odd and exciting coupled with the pleasant and ordinary – the jointly constitutes Yishun's unique place identity. Far from being unusual, this polysemic character of Yishun's place identity very much echoes the words of geographer Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh:

['The] interplay of past and present in the creation of place meanings is more complicated than it seems... Place meanings evolve with each inventive interplay of time and setting, varying with individuals and the unique conditions they find themselves... There is no singular meaning ascribed to a place nor a singular way of deriving those meanings.32

Phrased simply in the candid words of Yishun resident, Jude Leong Wei Zhong:

Besides the food available at Chong Pang Market & Food Centre, what I like most about living in Yishun is that it's close to nature – even my home at Springside Park is right in the midst of flora and fauna! Yet at the same time, I'm also aware that Yishun is known to others for its odd and quirky reputation. To me, that's also part of what makes this town endearing!33

Further Readings

Dorset, J. W., ed.

Who’s who in Malaya. Singapore: Dorset & Co., 1918.

“Kwang Tee Temple.” Singapore Chinese Temples 新加坡庙宇. Accessed March 8, 2018.

“Nee Soon Camp.” Remember Singapore.

“Report of the Pineapple Conference.” C218. Straits Settlements Legislative Council Proceeding 1931. August 31, 1931.

Savage, V. R., & Yeoh, B. S. A.

Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2013.

“Singapore ‘Then and Now’ Series: Yishun’s History with the Pineapple King.” Frasers Insider. Accessed February 21, 2018.

Solomon, Eli. Snakes and Devils:

A History of the Singapore Grand Prix. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2008.

Song, O. S.

One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984.

“Wah Sua Keng.” Singapore Chinese Temples 新加坡庙宇. Accessed March 8, 2018.

Wong, Mark. “Singapore: A Pineapple Canning Delight.” National Archives of Singapore. Accessed February 21, 2018.