TL;DR

Formerly home to the British Naval Base, Sembawang used to be central to the military defence of the British Empire, with thriving communities that sprang up around the base.

MUSESG Volume 15 Issue 1 – January 2022

Text by Stefanie Tham

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 15 Issue 1

Today a modern suburban town housing some 100,000 residents in mainly high-rise flats, Sembawang is not unlike most housing estates in Singapore. However, there is more than meets the eye when one digs deeper into its history: Sembawang used to play a central role in the military defence of the British Empire—HM Naval Base, built to protect British territories in Asia-Pacific, was located here.

For more than half a century since the 1920s, the naval base brought sailors and dockyard workers from around the world to this part of Singapore. The communities here were an international mix, and included people from Britain, Australia, India, Malaya and Hong Kong. The naval base also led to the establishment of satellite villages such as Chong Pang and Sembawang Village, which started out catering to dockyard workers and later matured into thriving socioeconomic centres.

Establishing a Naval Base

As early as 1919, Britain had identified Japan to be a serious threat to its empire in the Pacific. However, the First World War had exposed Britain’s limitations in protecting its overseas territories if it were to be engaged in a concurrent war in Europe. A naval fleet based in Asia was therefore deemed necessary to counter this threat.

At the time, the Royal Navy’s base in Hong Kong was too close to Japan— and thus vulnerable to attack—and its anchorage was too small for modern warships. The British government hence decided to build a naval base that was large enough to house its main naval fleet. Singapore was chosen as it was relatively far from Japan and strategically located among key trading routes between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh visits HM Naval Base, 1959. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Four potential sites north of Singapore were considered for their proximity to the narrow Johor Strait, which would have sheltered the base from an open sea attack. In 1922, Sembawang was selected as the site, and plans for the base were approved the following year, including accommodation and facilities for thousands of sailors.

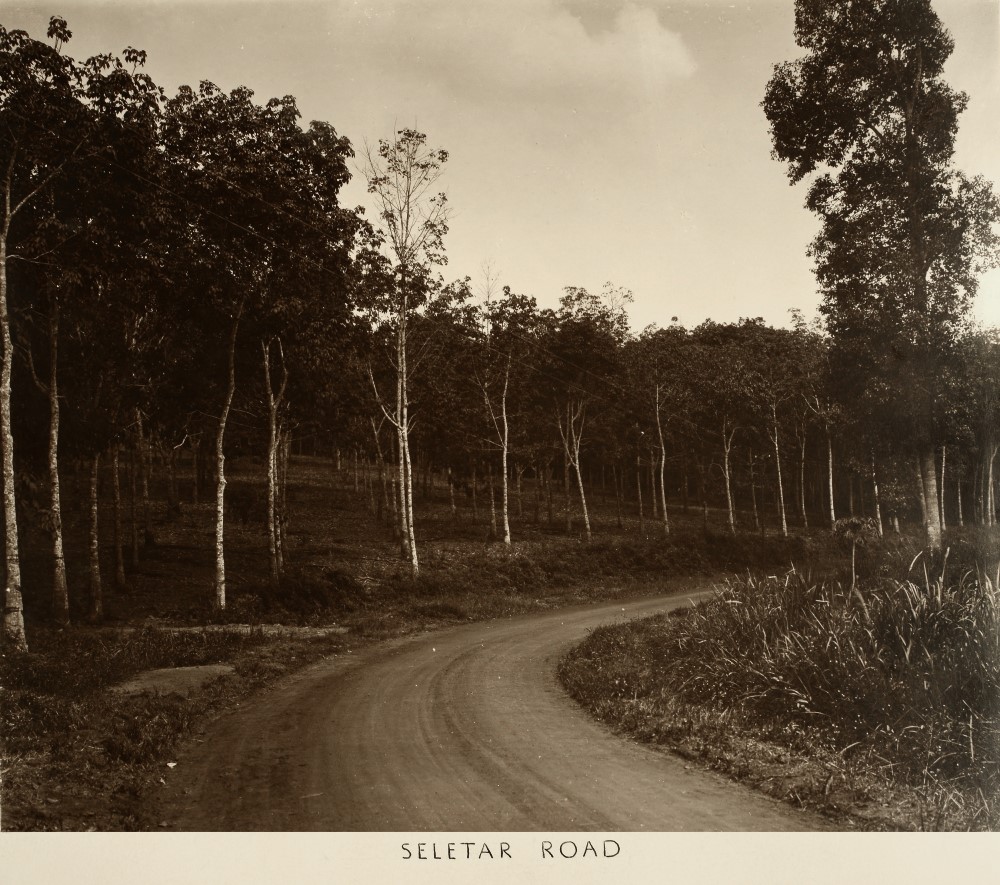

The decision to site the naval base in Sembawang permanently changed the physical and social landscape of the area. Like most of rural Singapore, the land in Sembawang had been used for the farming of cash crops since the early 1800s. By the 20th century, much of Sembawang was covered by rubber plantations, with most owned by Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company, which was set up by some of Singapore’s early pioneers including merchant Tan Chay Yan and Straits Chinese community leader Lim Boon Keng.

A rubber estate along Sembawang Road (then called Seletar Road), 1923–24. The National Archives, United Kingdom Collection

Rubber tappers working for Bukit Sembawang lived in houses built on land rented from the company, forming some of the earliest communities in the area. Lim Hoo Hong, who worked on the rubber plantations in the 1910s, shared in an oral history interview with the National Archives of Singapore:

“I was nine years old then, my mother went with me to tap the rubber. The two of us—mother and son—tapped two lots together, we made 80 cents a day. We built our home on the land that belonged to the Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company. They charged us a rent of only 50 cents a month.”

There was also the Orang Seletar, a boat-dwelling people who resided along the Johor Strait, as well as villagers who inhabited kampongs near the coast, which included Kampong Sembawang, Kampong Wak Tuang and Kampong Wak Hassan. These early communities were affected when the British took over swathes of land in Sembawang for the building of the naval base in the 1920s.

View from Seletar Pier, with the shoreline near Kampong Wak Hassan, 1920s. The National Archives,United Kingdom Collection

Sections of rubber plantations were cleared, and some villages as well as most of the Orang Seletar were relocated, while other settlements dispersed after the land was acquired by the British.

Besides local communities, some of the earlier establishments in Sembawang included seaside bungalows built by wealthy individuals who were drawn to the area for its scenic coastal location. These holiday getaways were located along the northern coast. One of them is Red House, which was built in 1919 by tycoon Joseph Aaron Elias, and another, Beaulieu House, was erected in the 1910s by businessman Joseph Brooke David. Both of these are still standing today. Such picturesque seaside houses were later also acquired by the British and adapted for new uses as part of the naval base.

Beaulieu House, 1920s. The National Archives, United Kingdom Collection

A Base Without a Fleet

Delays plagued the construction of the naval base, which dragged on for more than a decade due to vacillating directions from the UK government. Finally, in 1938, HM Naval Base, Singapore, also known as Sembawang Naval Base, was officially declared open by Governor Shenton Thomas. The centrepiece of the base was the 305-metre-long King George VI Dry Dock, which was then the world’s largest dry dock and could fit the Royal Navy’s biggest battleships.

Guests at the official opening of the naval base, 1938. From the Edwin A. Brown Collection. All rights reserved, Celia Mary Ferguson and National Library Board, Singapore 2008

Britain’s defence plan was to dispatch its fleet of battleships from Europe to the naval base in Singapore in the event of a seaborne attack by the Japanese. In the approximately five to six weeks before the fleet arrived, it was expected that Singapore would be defended by its artillery guns.

This defence plan fell apart quickly when the Second World War broke out in Europe in 1939. Despite its top-of-the-line facilities, the naval base never hosted the fleet it had been designed to accommodate. Britain was unable to send its fleet to Singapore as it was needed in naval confrontations with Germany. Instead, they dispatched a small squadron known as Force Z to deter the Japanese on 2 December 1941, but the Force’s capital ships were swiftly attacked by Japanese planes and sunk.

Dockyard workers in the blacksmith’s workshop, 1941. Australian War Memorial (00746)

Without a fleet, the naval base was indefensible. As the Japanese army gathered across the Johor Strait, the British decided to damage the docks and destroy their equipment to prevent enemy use, before evacuating the base by the end of January 1942.

Dockyard workers at the naval base, c. 1942. © IWM (K 785)

Postwar Life at the Base

Despite the swift end to the role of the naval base in the theatre of war, the base continued to be used in the subsequent decades after the Second World War. It was returned to the British following the Japanese Occupation, and was involved in the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), the Korean War (1950–53) and Indonesia’s Konfrontasi against the Federation of Malaysia (1963–66).

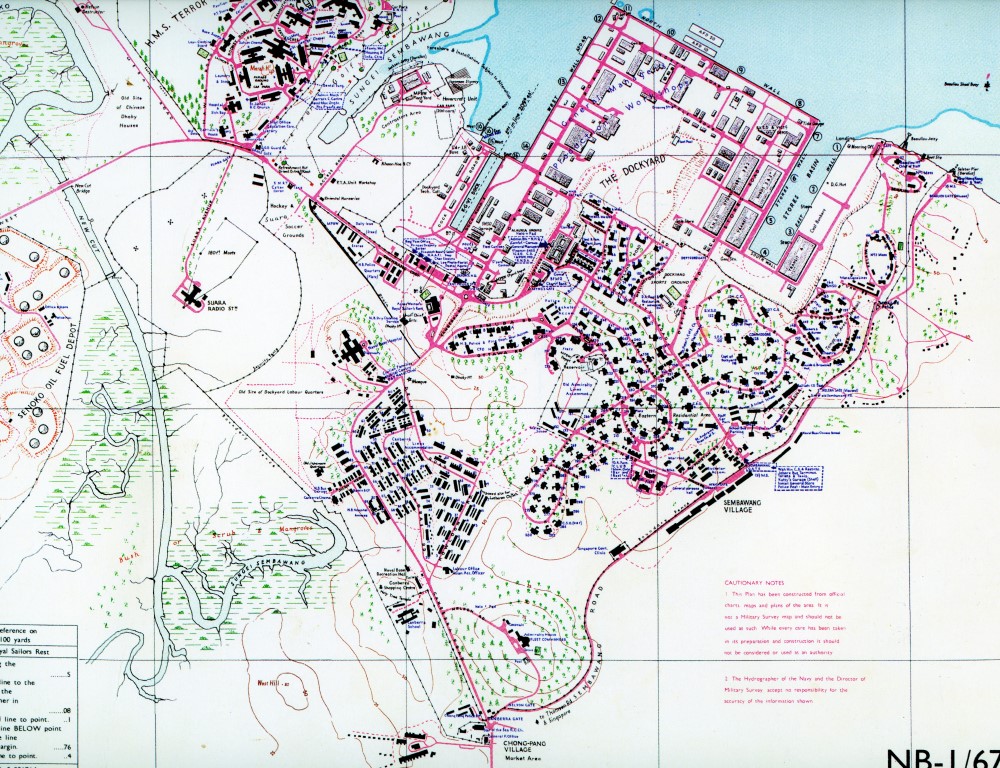

A map showing part of HM Naval Base, Singapore, 1968. Courtesy of Marcus Ng

During this postwar period, Royal Navy sailors who disembarked at the naval base resided at the Royal Navy Barracks, or HMS Terror. For sailors, docking at the base was a respite from the uncomfortable and stuffy quarters on board ships. Alan Tait, whose aircraft carrier HMS Centaur docked at the base in 1958, recalled:

“The accommodation at HMS Terror was on several levels with each having lovely cool balconies. We spent hours there writing letters home, chatting and playing cards. A short walk was a swimming pool. Tiger Beer flowed like water. After life on board, this was just about paradise.”

The thousands of workers at the naval base lived in quarters segregated by race and nationality. Europeans and Asian staff lived separately, with the former residing in the numerous black-and-white houses along Admiralty Road East. Asian workers lived in an area known as the Canberra Asian Quarters (or Canberra Lines), which comprised around 90 residential blocks along Canberra Road and three former side roads: Kowloon, Madras and Delhi Roads. These quarters were set aside not just for the workers, but also for their families.

Residents of Canberra Lines welcoming Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh during his visit, 1959. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Former residents of Canberra Lines described the community to be closeknit. Subhas Anandan, who had lived there in the 1960s, remembered it as such:

“People knew each other, the community was really united, we had no problems, racial problems, nothing. And we had Chinese, Malays, Malayalees, Tamils all living together.”

He also fondly recalled the community spirit among the workers:

“When the big ships come in, they open up the dry dock. The ship will come in and they will close it back. The water will go off but the fish that come in cannot go out. So the whole dock is full of fish and people are just going down and collecting the fish. People were very good in the sense that not everybody worked in the dry dock, you see. So those who were there would take [fish] and share with all the workers. So when the big ships come, it’s like a party, a carnival in the base, everybody having fresh fish.”

Dockyard workers during their daily commute, 1966. Courtesy of David Ayres

Most of the Chinese dockyard workers came from Hong Kong, which perhaps explains why Cantonese was the predominant Chinese dialect used by the workers. Leung Yew Kwong, who lived in Block 8 of Kowloon Road, described:

“My father, together with others from the Hong Kong dockyard, were transferred to the Singapore Naval Base in the 1930s. The naval ships in the dockyard, their cooks are usually Cantonese. So when they docked, he would invite them to our house and play mahjong.”

While the Asian dockyard workers were made up of people from Hong Kong, Malaya and Tamil Nadu, the majority were Malayalees who came from Keralain southwestern India. In 1960, there were around 5,000 Malayalee workers employed at the dockyard, leading some to nickname the naval base ‘Little Kerala’. Poravankara Balji, who lived on Delhi Road with his family, shared:

“The naval base was unusual as it was a little island and a secure place. One thing I valued being in the naval base was that it was a Little Kerala—the Keralan people were tightly knit. They even organised lessons in Malayalam. Even today I can still read and write Malayalam.”

A dance performance organised by the Naval Base Kerala Library, 1966. Ministry of Information and theArts Collection, courtesy of NationalArchives of Singapore.

Indeed, many of these naval base communities took charge to set up amenities and religious institutions to cater to their needs. For example, the Malayalees established a Naval Base Kerala Library in 1954 which housed thousands of Malayalam, Tamil and English books. The library also organised performances for the annual Onan festival celebrated by Malayalees of all faiths. Responding to the need for a proper place of worship for Muslim workers, Syed Amran Shah and his colleagues from the Naval Police Force raised funds to build Masjid Naval Base on Delhi Road.

The former Masjid Naval Base located at the junction of Canberra Road and the former Delhi Road, 1986. Courtesy of Loh Koah Fong

While the living quarters were segregated, one social activity that transcended ethnic lines was football. Work at the naval base ended at 4pm, leaving workers and sailors with plenty of daylight for a game of football at the empty field on Deptford Road. The matches were exciting events that attracted thousands of spectators who cheered for the different dockyard teams.

The football culture in the naval base even honed homegrown talents including Quah Kim Song, who later became part of Singapore’s national football team. Quah’s father, Quah Heck Hock, worked in the dockyard and resided at Block 80, Delhi Road. Another national player with roots in the naval base is V. Sundramoorthy, popularly known as the ‘Dazzler’, whose family lived at Block 75, Madras Road.

A football game at the Deptford Road playing field, 1966. Courtesy of David Ayres

Chong Pang and Sembawang Village

While the naval base had enough basic amenities for daily needs, there was a demand for more food options and other types of services. Locals saw the demand and jumped on this economic opportunity by establishing businesses and communities at the fringes of the naval base.

To the east of the naval base was the former Sembawang Village, which had been established in the late 1920s. Sembawang Village was also a transportation hub: Not only did it have buses that connected the village to Beach Road in the city, it was also a base for taxis, which brought residents to other parts of Singapore. By the 1960s, Sembawang Village had expanded to around 1,200 residents living in some 150 houses.

Rows of shops and bars at Sembawang Village, including Bluelight Café and Bar, 1967. Courtesy of David Ayres

Alan Tait recalled the diverse array of products sold at Sembawang Village:

"Sembawang Village was close by with its duty-free shops and bars. Cameras, watches, binoculars and all the usual were on offer at good prices. However, we were more fascinated with the toy shops. There were toys for sale that you couldn’t find in the United Kingdom… While we made our selections, we would be given a glass of Tiger Beer. The shopkeepers knew how to keep a customer happy."

The village was perhaps best known for its drinking holes and eateries that opened in the evening. The most famous stretch of bars was located in a row of shophouses at the junction of Admiralty Road East and Sembawang Road. Built in 1965 and known as the Sembawang Strip, it housed bars including Melbourne Bar Golden Hind, Ship Cabin and Nelson Bar. Former Royal Navy sailor David Ayres described the nightspot in its heyday in the 1960s:

"When I left Singapore in May 1964, there were about eight bars in Sembawang. Sembawang Bar was nearest to the naval base entrance. When I returned to Singapore in May 1966, there were more like 20 bars in Sembawang."

This popular row of shophouses, which still exists today, used to house bars including Melbourne Bar, Golden Hind, Ship Cabin and Nelson Bar. Courtesy of Sofea Abdul Rahman and Tony Dyer

A much larger neighbourhood with a wider range of shops was Chong Pang Village, which was located to the south of the naval base. Chong Pang Village was established on land owned by Lim Chong Pang, the second son of landowner and early pioneer Lim Nee Soon. The younger Lim saw an economic opportunity in the naval base and proceeded to convert a former rubber plantation into a residential area. The proximity of the village to the base attracted dockyard workers such as clerks, mechanics, cooks, laundrymen and domestic help.

By 1957, the population of Chong Pang Village had grown to around 11,000 residents. Chong Pang Village’s town centre was known for being a community hub where people gathered, shopped and went about their daily lives, or sought entertainment at the Sultan Theatre, which screened Hindi, Tamil, Chinese and English films.

Chong Pang Road, 1960s. Courtesy of Sofea Abdul Rahman and Tony Dyer

End of a Chapter

On 8 December 1968, a year after Britain had announced that it would withdraw its military forces from Singapore, HM Naval Base was transferred to the Singapore government. The dockyard was converted into a commercial shipyard under a new company, Sembawang Shipyard. Many of the base’s workers continued to live at Canberra Lines until the 1980s and 1990s when the quarters were cleared for the construction of new public housing flats.

Some of the former naval base workers still maintain close contact with each other via social media, and most of the stories in this article were uncovered through the active networks of former naval base residents.

Remembering Sembawang’s Pasts

In July 2021, the National Heritage Board launched the Sembawang Heritage Trail to explore the colourful history of the area as well as the diverse communities that had sprung up around the naval base. In this self-guided trail, participants can visit some of the former landmarks associated with the naval base and imagine what life might have been like for some of these communities.

Although some of the sites mentioned may no longer exist, the legacy of the naval base communities still persists in the community and religious institutions that have their roots in the base, and these serve as important tangible markers of social memory, reminding us of Sembawang’s varied, past lives.

.ashx)