TL;DR

From 1910 to 1940, the Lee Brothers Studio established itself as a cultural institution in colonial Singapore, capturing the rhythms of a bustling port city. Its success was grounded in the earlier efforts of Lee Tat Loon, Lee Tit Loon, and Lee Shui Loon, whose pioneering studios from the 1870s reflect Singapore’s cosmopolitan roots, the migration of Chinese overseas, and the creative ways locals navigated transnational commercial and knowledge networks through photography.The passing of Lee King Yan in 1957, fondly remembered as the "Colony's grand old man of photography," marks an important moment in Singapore’s visual history.[1] Although King Yan and his brother Lee Poh Yan are frequently celebrated as the faces behind the acclaimed Lee Brothers Studio, their legacy was built on solid foundations that had been passed down by their predecessors.[2]

Before the iconic Hill Street studio opened its doors, an earlier generation of Cantonese pioneers laid the crucial groundwork for establishing the infrastructure, networks, and expertise that would underpin the brothers’ later success. This article shines a spotlight on these lesser-known figures, tracing how inherited skills, entrepreneurial vision, and strategic positioning shaped the rise of photography as a cultural practice in twentieth-century Singapore.

Photography was introduced to Singapore as early as 1841 when Munsyi Abdullah documented an American ship doctor’s demonstration of the daguerreotype process in his Hikayat Abdullah.[3] Just two years later, in 1843, photographic portraiture services were already being publicly advertised. In the Singapore Free Press, G. Dutronquoy offered portraits at the London Hotel, claiming they could be completed “in the astonishing short space of two minutes.”[4]

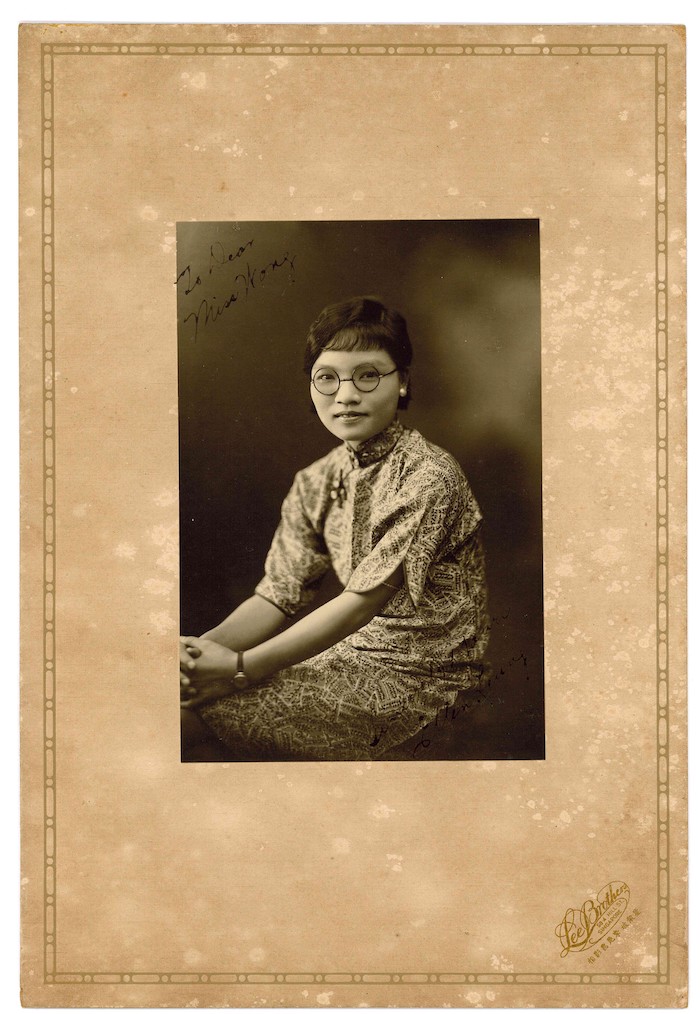

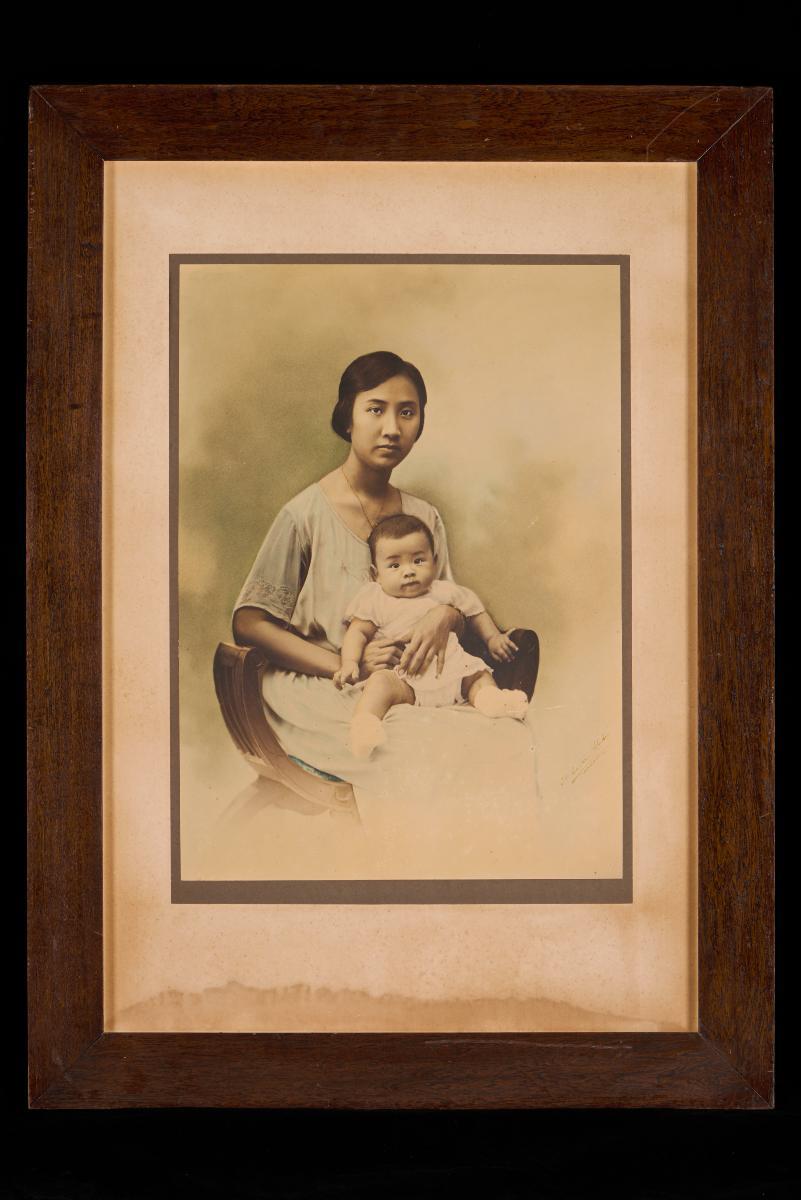

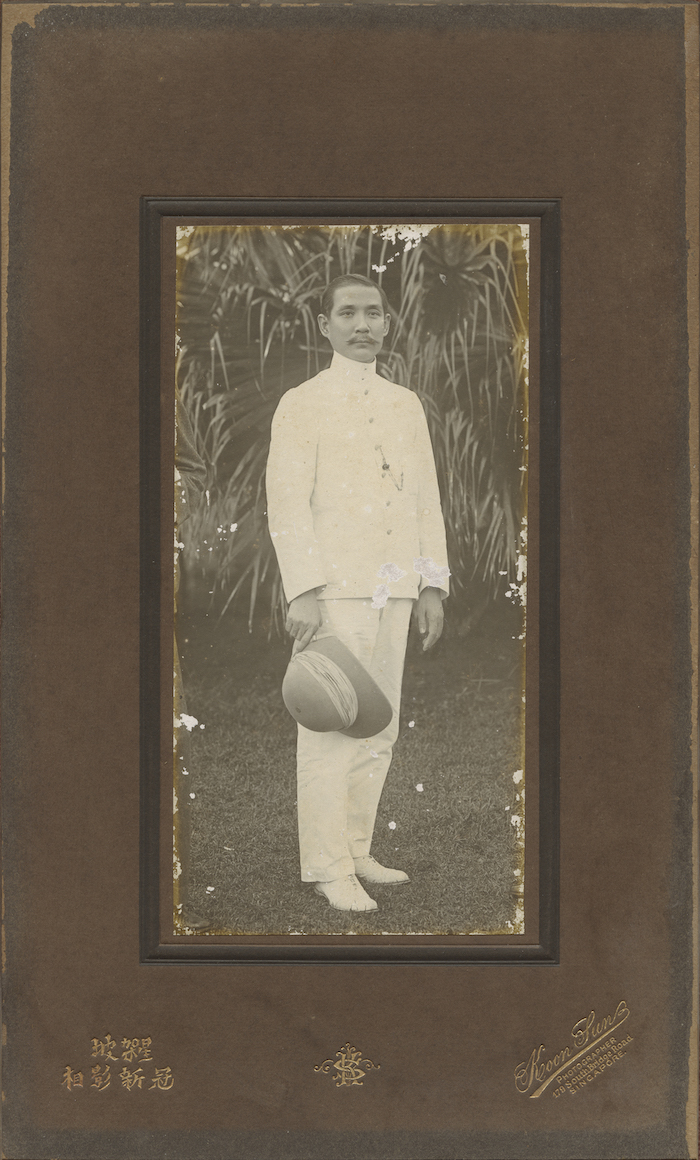

Though initially regarded as a colonial novelty, photography quickly became woven into the fabric of everyday life. While early photographic narratives tend to highlight European-run studios such as those led by John Thomson and G.R. Lambert, emerging Chinese-owned studios soon proved equally significant.[5] Among them, Lee Brothers Studio distinguished itself through technical excellence and a diverse clientele, documenting figures like Dr. Sun Yat Sen, buildings like the Great Southern Hotel, and major social organisations. Their work became a visual archive which captured Singapore’s urban transformation and evolving notions of modernity, identity, and selfhood.

Understanding how the Lee Brothers Studio emerged as one of Singapore’s most iconic photographic institutions requires looking beyond the well-known figures of King Yan and Poh Yan. While these brothers have become synonymous with the studio’s later successes, less attention has been given to the crucial groundwork laid by an earlier generation. Brothers Lee Tat Loon, Lee Tit Loon, and Lee Shui Loon were pioneering figures whose entrepreneurial vision, artistic training, and strategic use of diasporic networks significantly shaped the family's photographic enterprise. To fully appreciate their contributions, it is necessary to reconsider their roles within the wider context of identity formation, representation, and visual modernity among the Chinese diaspora in colonial Southeast Asia.

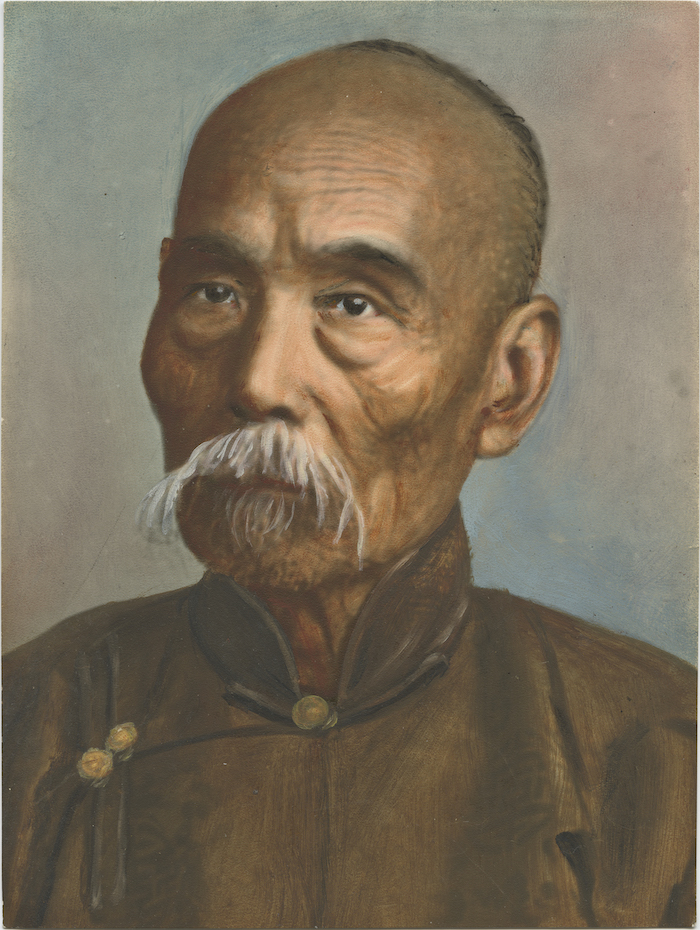

The Lee family traces its roots back to Siu Wong Nai Cheun (meaning small yellow earth village), located in Nanhai, Foshan, Guangdong.[6] Tat Loon, Tit Loon, and Shui Loon, representing the 20th generation of the family lineage, pivoted to the visual arts, diverging from the footsteps of their father, Lee Ting Mao, who was a nineteenth-century textile dyer.[7] Tat Loon first trained in portrait painting in Shanghai under his uncle Lee Feng Mao, with his younger brothers Tit Loon and Shui Loon receiving similar artistic education.[8] Their shift from painting to photography was sparked by a chance encounter: upon returning to his village, Tat Loon met an Anglican missionary who introduced him to photography and trained him in the craft, on the condition that he converted to Christianity.[9] This encounter profoundly reshaped the Lee family: not only did it introduce them to a new skill and trade, but it also significantly altered their daily lives, influencing family beliefs, traditions, and spiritual practices across subsequent generations. Photography thus became more than just a profession; it redefined the family’s identity and set the stage for their future prominence in Southeast Asia.

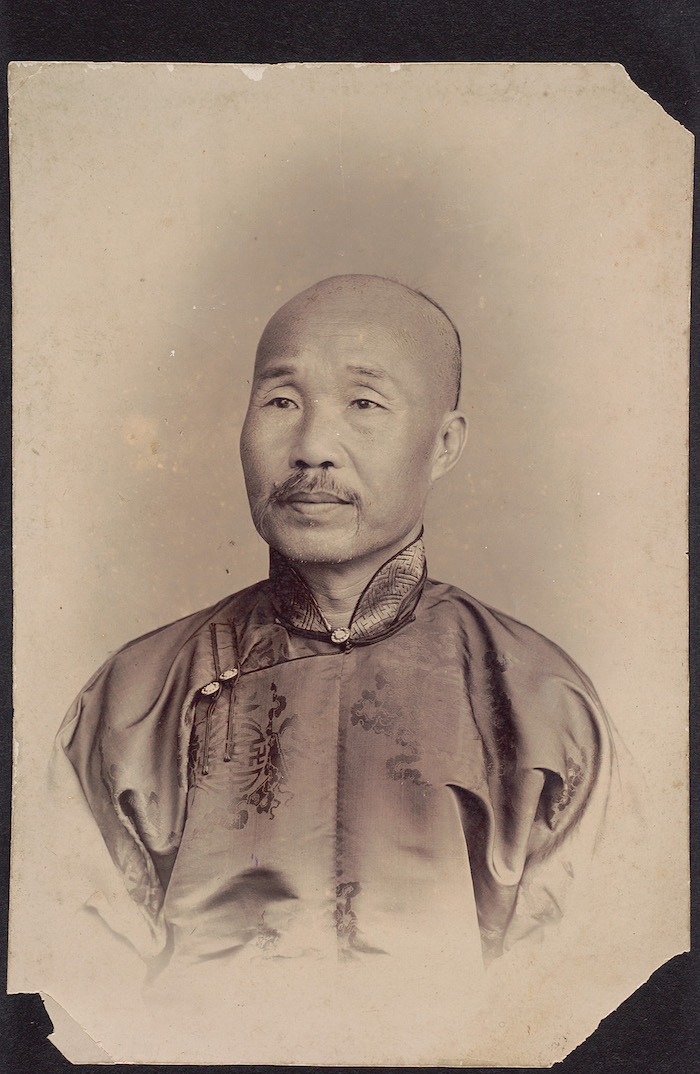

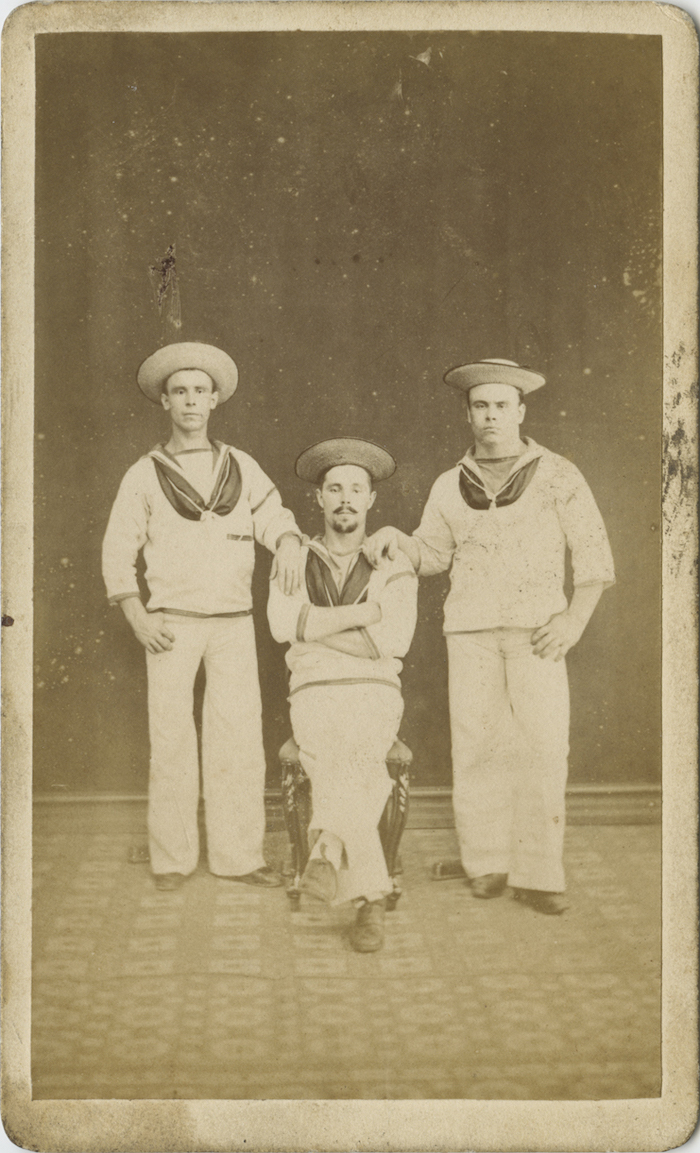

|

|

|

|

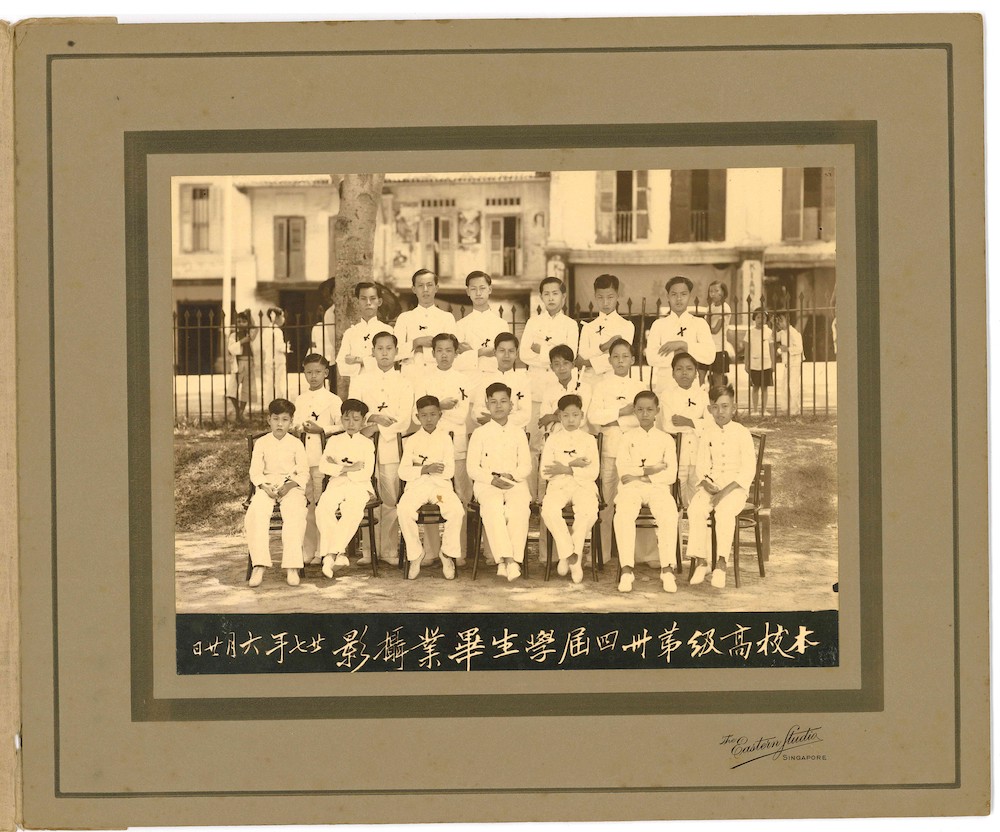

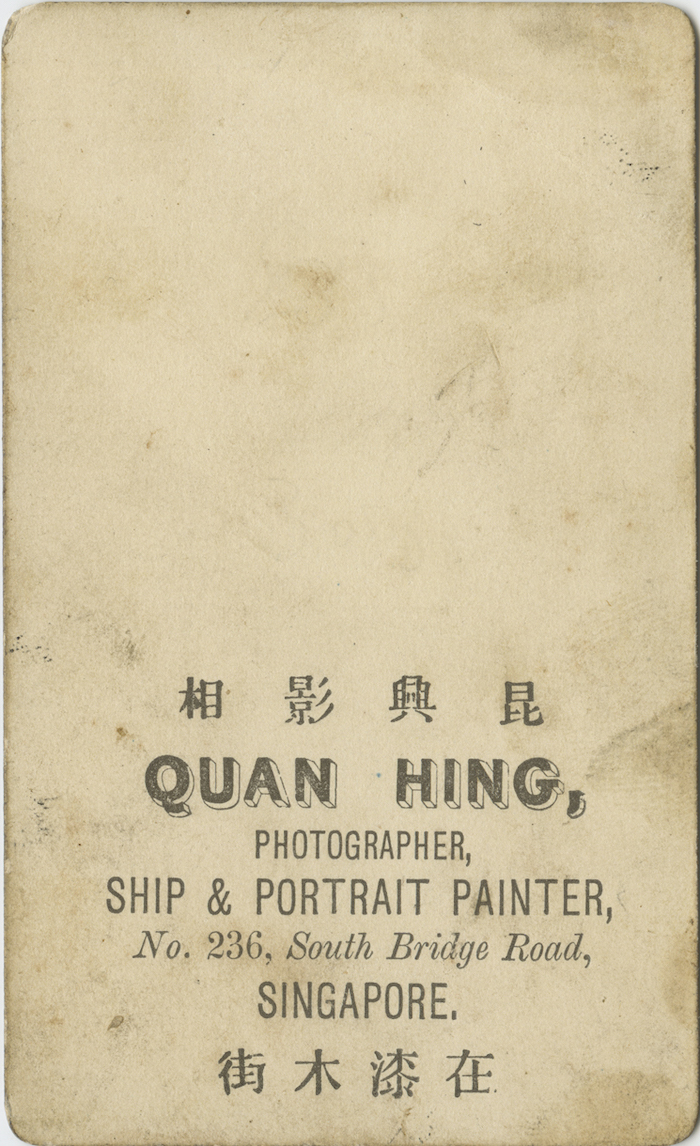

In the late nineteenth century, Tat Loon, Tit Loon, and Shui Loon migrated from southern China to Singapore, amidst a broader wave of migration driven by the upheavals during the final years of Qing dynasty and the lure of new opportunities in Nanyang.[10] In the 1870s, they established Quan Hing Photographer, Ship & Portrait Painter at 236 South Bridge Road, one of the earliest known Chinese-owned photography studios in Singapore.[11] Trained initially as portrait painters, the brothers brought their artistic sensibilities in their approach to photography, offering both photographic portraiture and ship painting services. Their practice reflected the needs of a bustling colonial port city and a clientele that included both local residents and itinerant maritime workers.

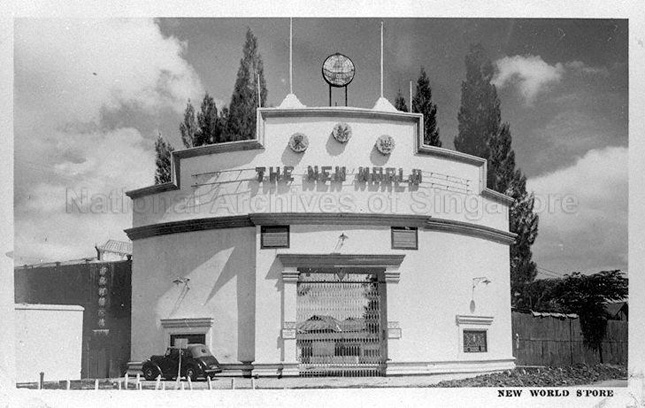

Quan Hing was founded at a time when Singapore was rising in prominence as a British colony and commercial hub in Southeast Asia. The city had become a frequent stop for international travellers, merchants, and traders. Major establishments such as Hotel de la Paix, Adelphi Hotel, Hotel de l’Europe, and the newly opened Raffles Hotel catered to a growing “tourist” population eager to experience the “exotic” and “oriental” tropics. Photographic formats such as carte de visites and stereograph cards featuring local scenes became popular souvenirs, fuelling demand for photographic services. Owing to such developments, Chinese-owned studios like Quan Hing began to flourish, especially along Upper Cross Street, Hill Street, and South Bridge Road. They capitalised on market gaps left by European-run establishments, offering smaller prints at more affordable prices.[12] In the competitive environment, Quan Hing stood out not only for its lower prices but also for its adaptability and craftsmanship.

While Quan Hing served as their initial base, Tat Loon and Tit Loon frequently travelled across the region to establish new studios, often involving relatives in the process.[13] On one such trip, Tat Loon brought Shui Loon to Surabaya, where he earned a modest fortune through photography.[14] Recognising his aptitude for managing studio operations, the two elder brothers eventually entrusted Quan Hing to Shui Loon while they pursued other ventures elsewhere.

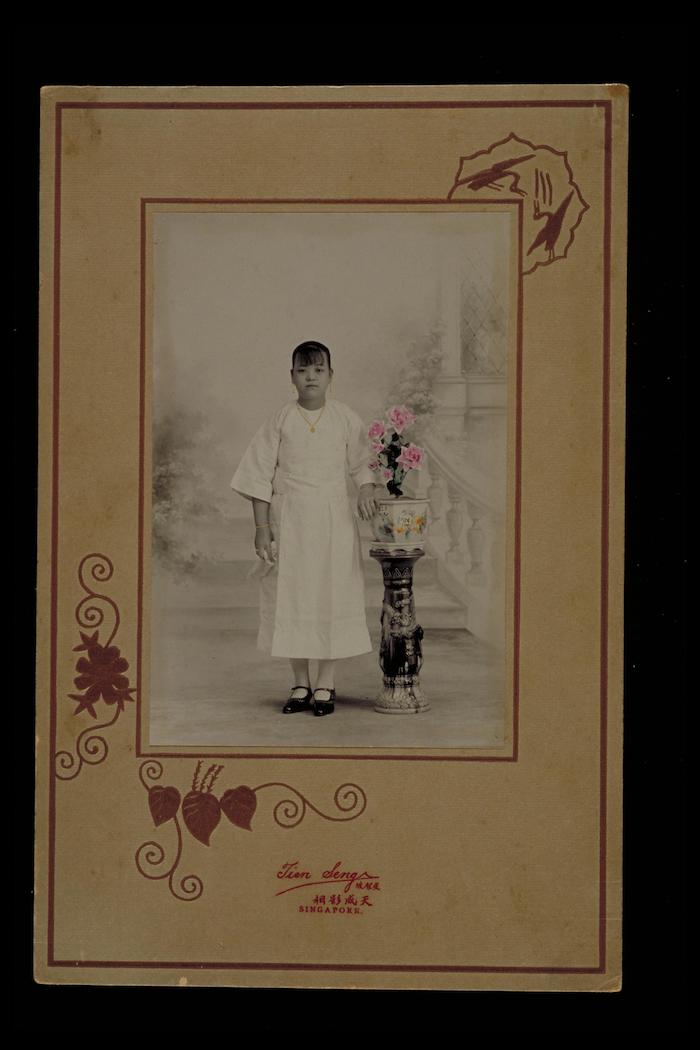

Shui Loon remained in Singapore and was the only brother to settle here permanently.[15] While managing Quan Hing Studio, he expanded the family's local presence by establishing new ventures, including Tien Seng at 396 North Bridge Road and Yong Fong Studios at 209 South Bridge Road, both of which would become integral to the family’s photographic legacy in Singapore.

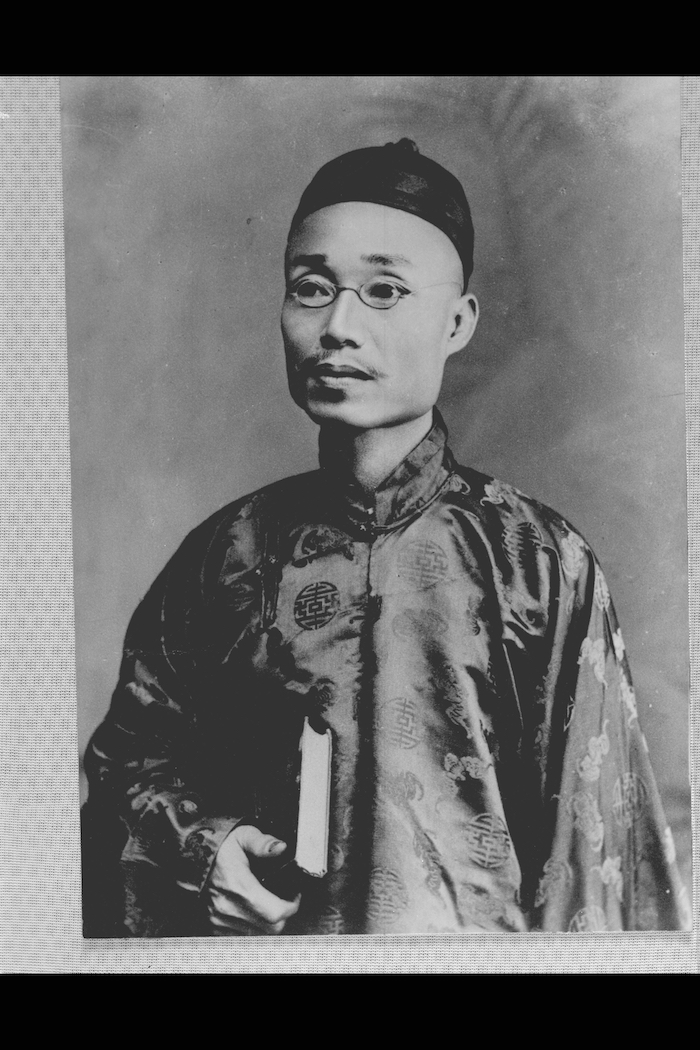

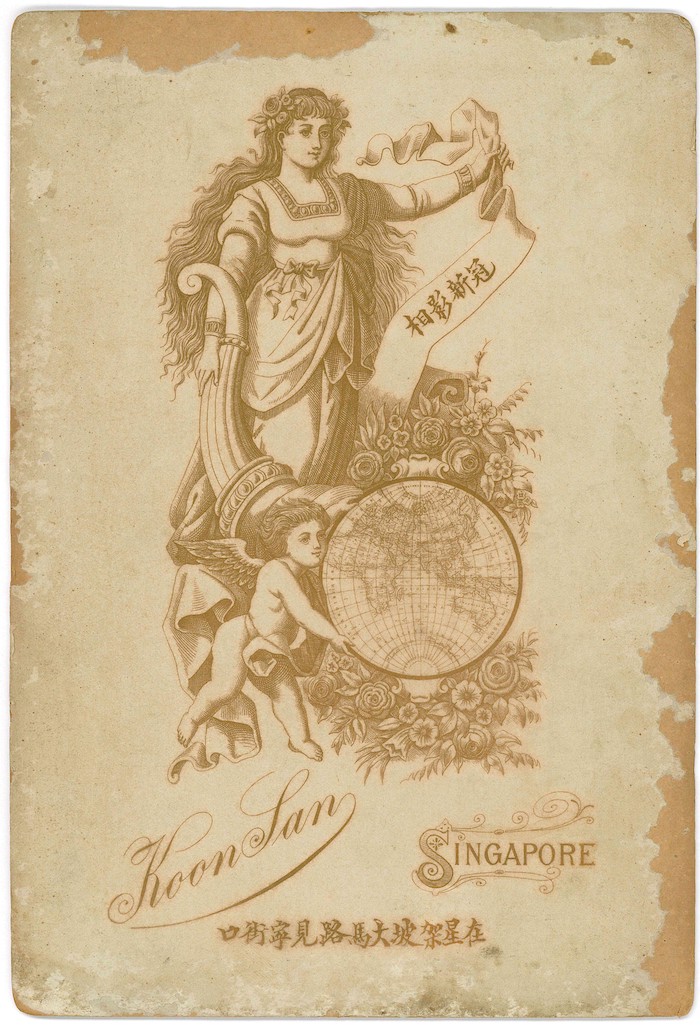

Meanwhile, by 1900, Tit Loon was managing the successful Koon Sun Photo Studio at 179 South Bridge Road. He had four surviving sons King Yan, Poh Yan, Sou Yan, and Chi Yan. Three became photographers: King Yan initially trained at Quan Hing, while Poh Yan and Sou Yan trained under their father at Koon Sun. After Tit Loon retired to his home village in China, Koon Sun was left in the hands of Poh Yan and Sou Yan. King Yan, however, struck out on his own and established Lee Brothers Photographers at 58-4 Hill Street in 1911. By 1913, Poh Yan had joined him, while Sou Yan continued operating Koon Sun until its closure around 1917.[16] Together, King Yan and Poh Yan transformed Lee Brothers Studio into one of the most prominent photography studios in twentieth-century Singapore.

Portrait of Dr Sun Yat Sen by Koon Sun Studio. Courtesy of Mr Loo Say Chong.

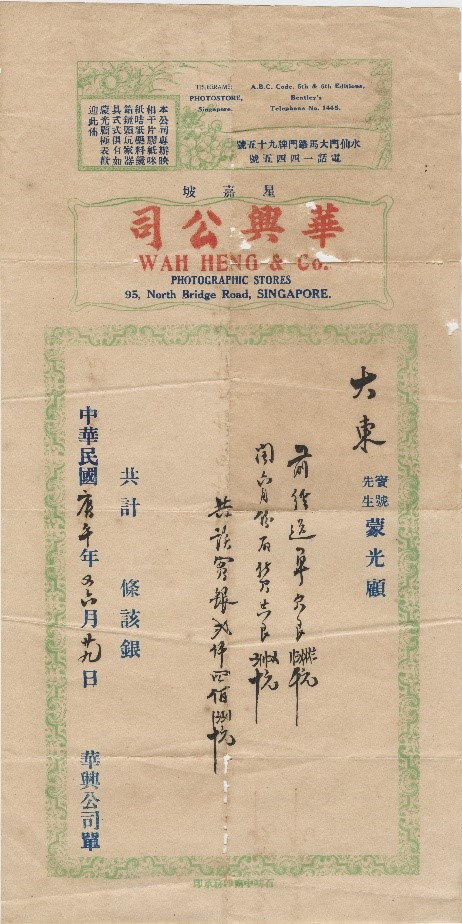

Shui Loon was not only active in opening photography studios; in 1909, he co-founded Wah Heng & Co. with his nephew Poh Yan at 95 North Bridge Road. Unlike the family’s earlier ventures that focused on studio photography, Wah Heng was a supply store offering chemicals, equipment, and printing services. It filled a crucial gap in the local market by reducing the reliance on goods from European suppliers which needed to be imported from places such as England.[17]It was also one of Kodak’s first agents in Singapore and Malaya[18] The store supported a growing ecosystem of amateur and professional photographers in Singapore and became a key part of the Lee family’s broader photographic enterprise. It also allowed their studios to operate at comparatively lower costs to their competitors.

World War Two marked a turning point for the Lee family’s photographic businesses. While Lee Brothers Studio had already seen a decline due to economic hardship and the rise of amateur photography, it was the war that led to its permanent closure.[19] Other family ventures, including Venus Studio and Eastern Studio, also ceased operations, with some suffering physical damage during air raids.[20] Only Wah Heng & Co., the family’s photographic supply store, resumed operations after the war under the management of Lee Hin Ming, son of Poh Yan.[21] It remained active into the 1960s, becoming the last of the Lee family’s photographic enterprises and marking the close of a legacy spanning three generations in Singapore’s visual and commercial landscape.

While King Yan and Poh Yan are often remembered as the public faces of the Lee Brothers Studio, this article has explored how their achievements were built upon the foundation laid by a preceding generation of brothers: Tat Loon, Tit Loon, and Shui Loon. Through a combination of artistic training, entrepreneurial initiative, and strategic use of family and regional networks, these early pioneers established the infrastructure, expertise, and kinship ties that enabled the family’s later success. The Lee Brothers Studio was one of the most luxurious and high-class photography studios in Singapore.[22] Their ventures not only sustained a growing photographic enterprise but also facilitated migration and expansion across Southeast Asia, forming a broad transnational network.

More than a family business, the Lee photography studios reflect the adaptability of early Chinese migrants navigating the pressures of modernity. In embracing photography, a medium at the forefront of technological and cultural change, they redefined their roles within a colonial society in transition. As this essay has traced, their legacy lies not only in the photographs they produced but also in the networks they built, the generations they trained, and the visual traditions they helped shape. Understanding their contributions offers a fuller picture of how photography became a vital site of identity formation, commerce, and cultural memory in twentieth-century Southeast Asia.

A Peranakan Wedding. Collection of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. Gift of Cheah Jin Seng.

Notes

[2] Eaton, Clay. “A Cenotaph for Singapore”. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 88, no.2 (2015): 25-50.

[3] Hikayat Abdullah is a Malay literary autobiography written by Munsyi Abdullah (1796–1854), a prominent Malayo-Muslim scholar, teacher, and writer who is often regarded as the father of modern Malay literature. Published in 1849, the text offers vivid firsthand accounts of early 19th-century life in the Malay Peninsula and Singapore. Its reference to a demonstration of the daguerreotype process around 1841 is considered the earliest known written record of photography in Singapore, making it a crucial source for understanding the region's early encounters with modern image-making technologies.

[4] Singapore Free Press, "Daguerreotype," Singapore Free Press, December 7, 1843. The development technology was first discovered in 1839 France and reached China within 2 months. However, it took approximately 4 years for the technology to arrive in Singapore. Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak, eds., Brush & Shutter (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011), 20-21.

[5] Although G.R. Lambert & Co. claimed to be the oldest photography studio in the colony (The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, April 19, 1909), John Thomson had already established a photographic studio at 3 Beach Road on June 16, 1862 (The Straits Times, June 14, 1862, 3, Advertisements column 1). G.R. Lambert officially opened his studio on April 10, 1867, at 1 High Street (“Notice,” The Singapore Daily Times, May 13, 1867, Microfilm: NL 5217).

[6] Founded in the 13th century by Lee Shun Tsai, a migrant from Zhejiang. He was a scholar during the Song Dynasty presiding in Jishui County of Jiangxi Province in Guangzhou. Gretchen Liu, From the Family Album: Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio, Singapore 1910~1925 (Singapore: National Heritage Board Landmark Books, 1995), 7.

[7] Interview with Mr. Kelvin Lee, grandson of Lee Shui Loon.

[8] From Lee family genealogy book, courtesy of Mr. Kelvin Lee.

[9] There are conflicting accounts of how Lee Tat Loon came into contact with photography. Some family accounts recall Lee Tat Loon meeting the missionary in China while others mention Tat Loon coming to Singapore and meeting a British pastor. Interview with Mr Kelvin Lee, grandson of Lee Shui Loon.

[10] It is important to clarify that Lee Yin Fun was an alternate (and favoured) name used by Lee Shui Loon. According to Mr. Kelvin Lee, great-grandson of Lee Shui Loon, this was a name he personally preferred. Family accounts confirm this identification, with Lee King Yan and Lee Poh Yan referring to Lee Yin Fun as their “third uncle.” Notably, Lee Shui Loon was the youngest of the three brothers, born in 1864, while Tit Loon was born around 1853.

[11] Ancestry book and family accounts refer to Quan Hing opening in the 1870s. However, the earliest record of Quan Hing in Singapore’s almanac is in the 1880. The Singapore and Straits Directory for 1880 Containing Also a Calendar and Appendix, (Singapore: Mission Press, 1880), 62.; The Singapore and Straits Directory for 1880 Containing Also a Calendar and Appendix, (Singapore: Mission Press, 1880), 62.

[12] Chinese photography studios like Quan Hing began to flourish alongside these developments, particularly along Upper Cross Street, Hill Street, and South Bridge Road. These studios capitalised on market gaps left by European-run establishments, offering smaller prints at more affordable prices. For instance, a 4-inch photograph at a Chinese studio in 1893 cost just 60 cents, while a European-produced carte de visite could still fetch up to five dollars as late as 1900. "Advertisement from G.R. Lambert," The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, June 11, 1900, 4.; "Advertisement from Great Eastern Studio," 星报, September 30, 1893, 2.

[13] For regional ventures, the brothers were constantly moving around the region. Lee Tat Loon later established Lai Sang Studios in Kuala Lumpur and Kwong Seng Photo Studios in Perlis, before eventually returning to China, where he passed away in 1904. Similarly, Lee Tit Loon opened studios such as Kuan On Photos in Penang and Chau Sui Hean in Lai Yong Village, China, and was recorded travelling through cities including Kuala Lumpur, Negeri Sembilan, Ipoh, Penang, Bangkok, and Semarang. He later returned to China to assist with the studio in Lai Yong. Lee Shui Loon, by contrast, remained in Singapore and continued operating local ventures until his death in 1935, providing continuity for the family’s photographic presence in the city. From Interview with Dr. Lee Lai Hung, grandson of Lee Tat Loon. Interview with Mr Kelvin Lee, grandson of Lee Shui Loon.

[14] Lee Shui Loon returned to his ancestral village and bought 3.795 acres of land which was a formidable feat recorded in the ancestry book. From Lee family genealogy book, courtesy of Mr. Kelvin Lee.

[15] Lee Shui Loon passed away on 13th December 1935 in Yong Fong Studios at between 7-9pm, at the age of 71.

[16] Gretchen Liu, “Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio,” BiblioAsia, National Library Board Singapore, April 30, 2018, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-14/issue-1/apr-jun-2018/lee-brothers/.

[17] Lee Hin Meng, "Vanishing Trades, Accession Number 001487," by Irene Quah, National Archives of Singapore, oral interview, May 17, 1994.

[18] Mr Kelvin Lee recalls from family accounts that Wah Heng was one of the first Kodak agents in Singapore, and possibly in Malaya. Interview with Mr Kelvin Lee, grandson of Lee Shui Loon.

[19] Gretchen Liu, “Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio,” BiblioAsia, National Library Board Singapore, April 30, 2018, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-14/issue-1/apr-jun-2018/lee-brothers/.

[20] Venus and Eastern Studios were photography ventures established by Lee King Yan. Gretchen Liu, “Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio,” By the early 1920s, the two brothers parted company on amicable terms and King Yan opened Eastern Studio on Stamford Road. BiblioAsia, National Library Board Singapore, April 30, 2018, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-14/issue-1/apr-jun-2018/lee-brothers/.

[21] Wah Heng reopened after the war, run by Lee Hin Ming, first son of Poh Yan. The supply store eventually closed in the 1960s due to rent and competition, closing the curtains on three generations of photography studio legacy. Lee Hin Meng, "Vanishing Trades, Accession Number 001487," by Irene Quah, National Archives of Singapore, oral interview, May 17, 1994.

[22] Lee Hin Meng, "Vanishing Trades, Accession Number 001487," by Irene Quah, National Archives of Singapore, oral interview, May 17, 1994.