Text by Ang Zhen Ye

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

There is a multi-storey dwelling which is one of the most highly sought-after “residences” in Bishan. Home to many, including my great-grandmother, this prime location is always alive with chatter whenever my family visits. Yet, no one really lives in these blocks of “flats”. Indeed, far from catering to the living, Peck San Theng is a final resting place for the dead.

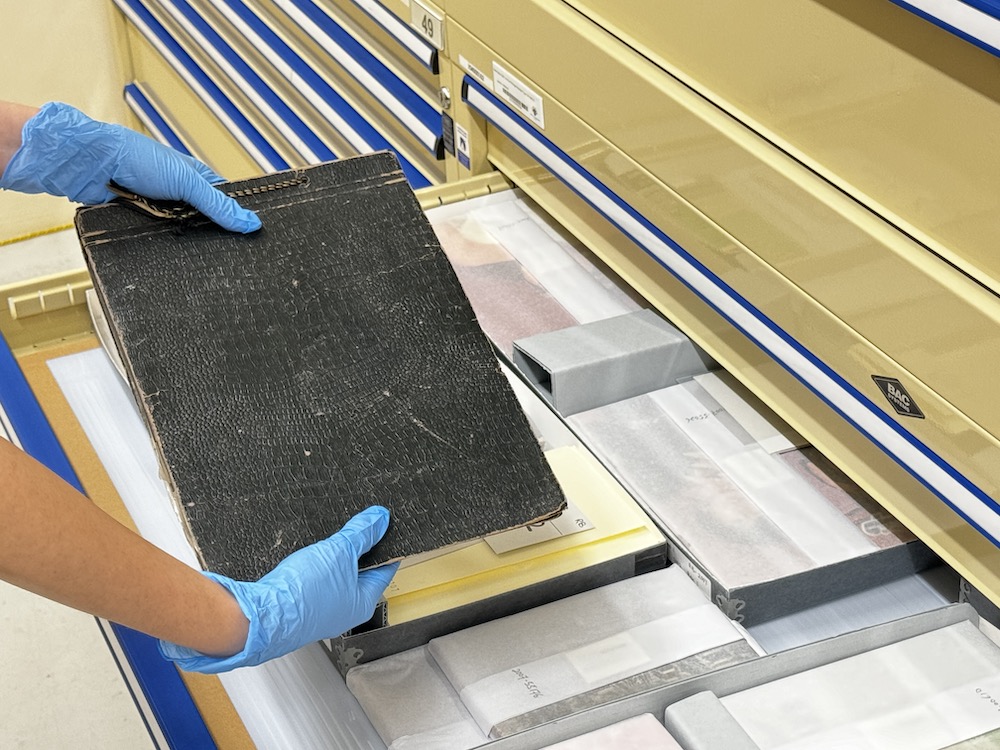

The columbarium in Peck San Theng (Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng), which was opened in 1986, is touted as a “condo for the dead”, and can house up to 90,000 occupants. Still, when compared to the Peck San Theng cemetery of the past, which used to occupy 384 acres, this columbarium is relatively small. My great-grandfather, who passed on decades before his wife and the building of the columbarium, was buried in one of the graves in the cemetery. During the government’s mass grave exhumation in the 1980s, my family had to dig for my great-grandfather’s remains to move him to the new columbarium.1 Unfortunately, my family’s effort to locate his remains proved to be futile. Today, he is forever lost to the ground underneath the tall, modern buildings.

Incidentally, my family moved to Bishan in 2011 and we are now closer to – or perhaps even living on – the final resting place of my deceased great-grandparents. This daily reality seems to be fundamental to Bishan’s heritage: whether it is inhabitants of Bishan Town or villagers from the former Kampong San Teng, Bishan’s residents have always been living with the dead. How then do residents today live, interact, or even reconcile with the dead? And how has this notion of “living with the dead” evolved from Kampong San Teng to Bishan?

Kampong San Teng – A Town Built around the Dead

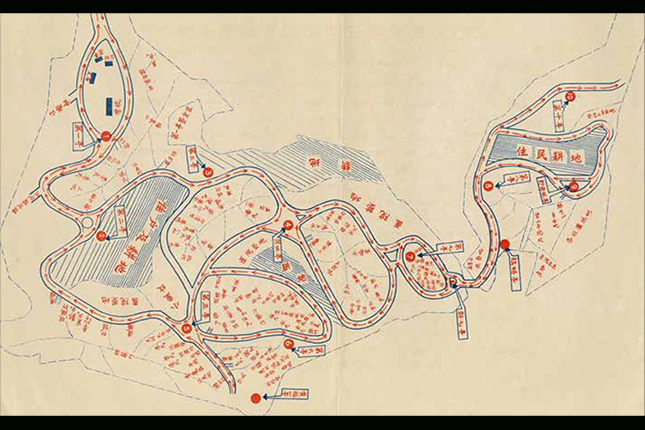

The name “Bishan” is the pinyinisation of its Chinese counterpart Peck San (碧山), derived from Peck San Theng (碧山亭) Chinese cemetery. Founded in 1870 by three pioneers from Kwong Fu, Wai Chow Fu and Siew Hing Fu prefectures in Canton, China, the cemetery was run by a federation of 16 clans belonging to the Cantonese community in Singapore.2 The cemetery started as a burial ground for the Cantonese, but eventually included other dialect groups and races. As the cemetery expanded over time, it was divided into a series of “hills” and “pavilions”.3

To locate a particular grave, one must first find the “hill” or the “pavilion” number – for example Wong Fook Hill, Pavilion No. 5 (黄福山, 第五亭) – before navigating through the thick undergrowth within the section to find the grave. This gave rise to the name “Peck San Theng”, which means “Pavilions on the Jade Hills”.

Following the establishment of Peck San Theng, people began to settle around the burial grounds. At first, the small community consisted of cemetery caretakers, gravediggers, peddlers selling ritual-related goods and others in charge of honouring the dead. Later on, with the influx of Chinese immigrants during the early 20th century, the community bloomed into a kampong known as Kampong San Teng.4 However, even with the rise of new landmarks – a Chinese school, traditional teahouse, wet market, and an open-air cinema, the highlight of village life still revolved around the annual festivals for the dead, including Double Ninth Festival (重阳节), Qing Ming Festival (清明节) and the Hungry Ghost Festival (中元节).5

Be it cutting the grass to find the graves, preparing food in the teahouse or setting up theatrical performances or rites, the entire community would engage and interact with the dead during these three festivals. While most would have heard about the Qing Ming and Hungry Ghost festivals, not many people today know about the Taoist Double Ninth Festival. The Double Ninth Festival is held on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. During this festival, people would carry a dogwood plant, climb the hills, drink chrysanthemum wine, and eat chong yang (重阳) cake.6 Many believed that the higher one climbed, the more successful one would be.7 In addition, Kampong San Teng would also organise theatrical performances (getai), lion dances, and sacrifices and offerings for the spirits. Even secret societies would participate in this festival. However, instead of commemorating Huan Jing, a mythological hero who defeated an evil monster, the local gangs would choose to worship a martyr who died while engaging in secret society activities. For smaller gangs without such martyrs, they would worship a deity called Ah Phoh San (阿婆神).8

Activities that were associated with the dead did not only happen during these festivals. Being next to the cemetery, villagers interacted with the departed on a daily basis – often in various interesting and surprising ways. Children, for instance, played hide-and-seek in the cemetery without fear. Even when they fell into open graves, some would take the opportunity to “fish” from the graves! Loh Soo Har, a former villager and teacher at Peck San Theng Chinese School recounts:

As the village area was surrounded by trees, it was not so suitable to fly kites there, so we would go on top of the hills... Sometimes, when we accidentally broke the string of the kite, and had to chase after the body of the kite, we would fall into [empty] graves. Sometimes, we would discover fish in the graves. Usually, people would put a water tank beside the coffin. Strangely, catfish started growing inside, and I even caught a few myself. At that time, we even sold them for money! You could say that we took the cemetery as a playground!

However, it was not as if there was no fear of the supernatural. Ng Su Chan, a former villager, recounts that his friend “walked into a ghost (and had) a high fever... for seven days, but miraculously after seven days, he recovered”.9 Such stories of other worldly beings and mysterious ailments were common and almost every villager had a personal story to tell.

Secret societies, on the contrary, did not fear the cemetery. Rather, local gangs enjoyed a cordial relationship with the dead, resulting in much lawlessness in the area. The origins of this lawlessness can be traced back to Toa Payoh in the 1950s and 60s.

Toa Payoh then was popularly known as the “Chicago of Singapore” or the mafia district of Singapore. Much of these gangster activities spilled over to Kampong San Teng, which was considered an extension of Toa Payoh. Furthermore, the quiet and secluded nature of the cemetery made it ideal for secret societies such as Flying Dragon (飞龙) and Harmony Peace (和平) to carry out gangster activities there.10 This is illustrated in several incidences in the 1950s. On 25 June 1950, two men were caught with over one ton of unpaid-duties tobacco. In an attempt to arrest illegal distillers, the customs police, on 20 November 1954, faced off with a “menacing mob of 60 men armed with sticks”. The mob surrounded the police, allowing the criminals to escape in the scuffle.

Due to its reputation for housing many secret societies, Kampong San Teng also became the logical place to investigate criminal activities, such as the kidnapping of multi-millionaire Tan Lark Sye’s nephew in 1957. These secret societies were also hostile to one another. Armed with parangs and guns, they often clashed with each other on the hills. The police were understandably hesitant to enter the cemetery and rarely patrolled the area, not to mention taxi drivers who avoided the place altogether. Peck San Theng cemetery, in one of the administrator’s words, was truly “messy and lawless”.

Seeking Refuge among the Dead

On 13 February 1942, during the Second World War, a critical battle between the British and the Japanese took place on the cemetery grounds. On one side was the 2nd Battalion of the Cambridgeshire Regiment, 5th Royal Norfolk Regiment, 5th Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiments, and on the other, the lead elements of the Japanese Imperial Guards. The first engagement was a surprise hit-and-run bayonet attack at 11.30pm. Shortly after, the fighting intensified and both sides suffered heavy losses. Still, the 2nd Cambridgeshire Regiment managed to hold their position on knoll No. 90 (located somewhere between Pavilion No. 1 and 3). The final orders came on 15 February at 3.30pm: a half-hour ceasefire. Approximately two hours later, General Percival officially surrendered to the Japanese.11

During the start of the Japanese invasion, especially after the bombing of Chinatown, many Chinese – most famously the Samsui women – moved to seek refuge among the tombs.12Their belief that Peck San Theng would be safer was unfortunately false. Not only did a fierce battle take place in Peck San Theng, the kampong was also bombed by the Japanese. Lim Choo Sye recounts:

It was the first time I had... such an experience of seeing how much damage bombs could do to a village... full of attap houses... it was an experience one can never forget, having seen so many houses flattened. A few people died, killed by the blasts, not so much by the bombing. There were a few limbs hanging on trees and all the trees had no more leaves.

Nevertheless, while the kampong cemetery was ravaged during the Japanese invasion, life during the occupation itself was rather peaceful. Compared to the urban city areas, the Japanese left the kampong cemetery relatively untouched. The place was spared due to a few possible reasons: the Japanese fears of offending the dead, the importance of the village as a food producer, and the perception that the rural Chinese were less dangerous than their urban counterparts. Those who sought refuge among the dead recalled that they were never called up for forced labour or screenings (Sook Ching operations) and lived a safe life in Kampong San Teng.13

From Peck San to Bishan

In September 1973, the government issued an order to stop all fresh burials and closed the cemetery. Six years later, Peck San Theng’s land was officially acquired for urban development. The notice for exhumation was given in November 1979 and from 1983 to 1990, Peck San was redeveloped into Bishan Town.

Kampong San Teng and its residents were also resettled to other new towns, with most moving to Ang Mo Kio.14 With the dead now occupying a much smaller space at the columbarium, how did modern residents go about living, interacting, or reconciling with the dead at the margins of the town? The answer seems to lie in both the architecture and the urban myths of the town.

Peck San Theng may be physically gone, but its pavilions live on in the architecture of Bishan’s Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats. These iconic pavilion-inspired HDB roofs were popularised by Singapore’s sitcom series Under One Roof in the 1990s. More than a simple reminder about Bishan’s ghostly past, Under One Roof romanticised the ideal Singaporean life: living in a prime location 5-room HDB at with children who were well educated – a marked departure from the taboo of living with the dead.

Urban myths about Bishan are yet another form of interaction with the dead. Just as how ghost stories were rife in Kampong San Teng, new residents of Bishan Town had their own supernatural experiences to share. These myths persisted and were even published in The Straits Times in an article titled “Is Bishan MRT ‘unclean’?”

It is late at night and you are on the last train... The train, which is bound for Kranji, pulls into Bishan MRT station and you prepare to alight. To your astonishment, it does not stop. Furious, you confront the driver and demand to know why. He asks you how many passengers you saw waiting on the platform. 10 to 15, you say. He replies: “I saw more than 50 people and some were without faces. That’s why I didn’t stop.”

Even today, Bishan station is considered one of the most haunted places in Singapore. There are many different stories of faceless, headless, or other worldly beings terrorising the station at night, all fuelled by the fact that the station does sit over former graves.15 Conversely, many also consider Bishan to be a place with good fengshui.16 As Kenneth Pinto puts it,

When the place started getting more popular with people because it was quite central, then things got twisted around... Because of the cemetery’s high ground, you got good views, supposedly good fengshui. And, yeah, conveniently forget all these ghost stories.17

Concluding Thoughts: The Dead as a Reflection of the Living

In many ways, the legacy of the dead is reflected in the lives of the living. Just as how the dead moved from jade hills to “condos”, the living too moved from kampongs to high-rise flats. What is currently home to some 90,000 Singaporeans was once an idyllic resting place for more than 100,000 Chinese migrants. Yet, in this process of turning squatters to citizens, many former kampong residents feel a sense of longing for the past; a sense that they have lost a familiar way of life, relationships, and people, in exchange for modernity and a new way of life.18 That is not to say that the choice to develop was wrong.

Without having moved the graves, I wouldn't be able to live in Bishan and enjoy its modern facilities. But there is something nostalgic - even for a new resident like me - to be so closely associated with the dead. This nostalgia cannot be substituted by pavilion roofs or urban myths. Perhaps the best way to reconcile with the past to remember its history: just as how I remember the elusive great-grandparents that I "live" with today

Further Reading

1. Cheong, Colin, Anthony Thomas, Bishan East Grassroots Organisation (Singapore), and Bishan-Toa Payoh North Grassroots Organisation (Singapore). I Love Bishan: Celebrating Community Building in Bishan. Singapore: Published for Bishan East and Bishan-Toa Payoh North Grassroots Organisations by Times Editions, 2001.

2. Tan, Kevin and Singapore Heritage Society. Spaces of the Dead: A Case from the Living. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2011.

3. 李国樑. “碧山亭的起源与重建.”《 扬》,第35期.

4. 岑康生/陈翠玲秘书 整理. 广惠肇碧山亭大纪事.

5. “清明扫墓 Qing Ming.” 从夜暮到黎明 From Dusk to Dawn. April 7, 2017.http://navalants. blogspot.sg/2017/04/qing-ming.html. Accessed March 01, 2018.

Notes