Text by Marcus Ng

Be Muse Volume 6 Issue 3 – Oct to Dec 2013

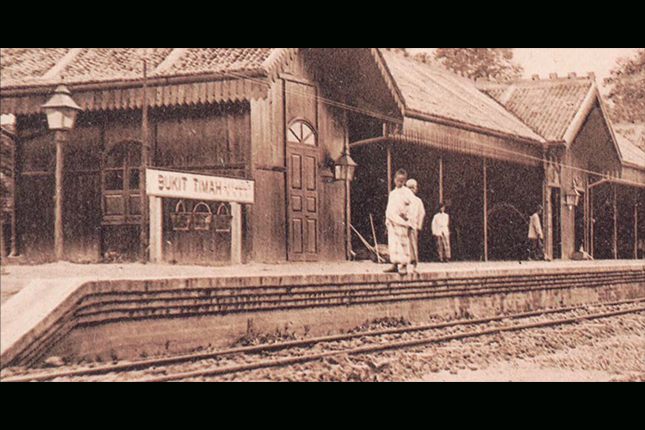

For more than 80 years at the time of writing, the Bukit Timah Campus has served as “the cradle for tertiary education in Malaysia and Singapore”, a landscape of learning amid wooded hills and elegant halls of study where students matched wits with their professors and mingled with their peers. Today in 2013, the campus forms part of the National University of Singapore, housing the Faculty of Law, Asia Research Institute, East Asian Institute, Institute of South Asian Studies, Middle East Institute and Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. Its origins lie, however, in Raffles College, which was set up at 469 Bukit Timah Road in 1928 as an institution of higher education in the arts and sciences, the long-delayed result of a colonial effort to mark the centenary of the founding of modern Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819.

In 1949, Raffles College was merged with the King Edward VII College of Medicine (founded in 1905 on the former Sepoy Lines, now the site of the Singapore General Hospital) to become the University of Malaya. Two other major mile ones for the institution came in 1962, when it was renamed the University of Singapore, and 1980, when the University of Singapore was merged with Nanyang University to form the National University of Singapore (NUS).

After NUS shifted from Bukit Timah to Kent Ridge in 1981, the Bukit Timah Campus housed various other tertiary institutions, including the National Institute of Education and the Singapore Management University. NUS returned in 2006, when the Faculty of Law and a number of research institutes moved to the grounds of the old Raffles College.

Bukit Timah Campus: an architectural profile

The revival of the Bukit Timah Campus as a centre for higher learning and research also led to a rejuvenation of the buildings that had arisen over the decades. The layout and structure of the original Raffles College was based on a draft by Cyril A. Farey and Graham R. Dawbarn, two Englishmen who won an Empire-wide competition to design the new institution. The core of the college was set on a hill with gentle slopes, with the Botanic Gardens to its rear and a broad plain (where playing fields would later be created) between the buildings and Bukit Timah Road. In outlook, the architecture was a clear departure from earlier, classically inspired structures, combining as it does a modern penchant for simpler yet stately and elegant patterns, with adaptations for tropical heat.

The original complex enclosed two quadrangles, grassy courtyards surrounded by long halls with covered walkways and wide arches on the ground level. The upper storeys had windows with no pilasters (projecting columns) and supported tiled roofs, pitched high for air circulation. The Manasseh Meyer Building, which bisected the courtyards, featured a pylon-like roof tower and flattened domes or copulas at both ends. Serving as the gateway to the college from Bukit Timah Road was the Oei Tiong Ham Hall, which faced a circular driveway and bore prominent arches that supported a long upper gallery. A new wing, named Block A, was added in the 1940s, followed by a Library in the 1950s and a landmark Science Tower in 1966.

In recognition of their significance and value to the civic and educational development of Singapore, six buildings that make up the former Raffles College were gazetted as National Monuments by the National Heritage Board on 11 November 2009. This status as a site protected from redevelopment encompasses the Oei Tiong Ham Building, former Library Building (now the CJ Koh Law Library), Manasseh Meyer Building, Federal Building, Eu Tong Sen Building and Li Ka Shing Building (formerly Block A). Also included were the two quadrangles of green space located within the complex.

A studied approach to a space of learning

To ensure that the Bukit Timah Campus could continue to serve the needs of undergraduates and researchers in the 21 century, NUS embarked on a programme to restore and upgrade the former Raffles College facilities. This project, led by Forum Architects, sought to uphold the buildings’ architectural legacy as the foundation of tertiary education in Singapore and Malaysia, while adapting the halls and rooms to serve as classrooms and lecture theatres equipped with modern technologies.

In their study and documentation of the campus’s architectural evolution, the architects uncovered several modifications and additions to the buildings over the decades. For one, the original doors on most of the blocks had been replaced, while those on the Eu Tong Sen Building had been removed; these doors were painstakingly reinstated to their design detailing and rightful locations. At the Oei Tiong Ham Block, a surprise discovery was the original coffered ceiling above the lobby; the panels were restored with great sensitivity, as was a link between the building and Block A that had been severely altered. These measures helped to revive much of the original soul, details and aesthetics of Raffles College, which many of its alumni would recall with fondness.

Meanwhile, the quadrangles where students traditionally gathered to debate and discuss each other’s work had endured insensitive alterations and additions, such as covered structures along walkways that were added with little thought for integration. These changes clashed with the original design intent of the campus. To rectify this, the architects dug into the archival plans to reinstate the original link between the Oei Tiong Ham and Manasseh Meyer Blocks. A minimalist design approach was taken to bring elements of the original architecture to the fore; mature trees in the grounds, including a magnificent angsana planted not long after the campus was built, were retained and the quadrangle lawns underwent fresh landscaping to give greater prominence to the surrounding buildings. Along the corridor of Block B (before the upper quadrangle, facing the Federal Building), new decks planted with native sea gutta trees were added to provide a tiered landscape and spaces where students can mingle and relax under natural shade.

Though naturally ventilated in its early years, the buildings had to be adapted for air-conditioning. This was done with subtle touches; louvered windows were reinstalled and fitted with glass panels to keep cool air indoors, while ductwork and diffusers were carefully hidden from view. The architects also employed new technologies and novel methods to create a sense of greater, column-free space within the graduation hall of the Oei Tiong Ham Building.

In this restoration and revitalisation of the former Raffles College, the architects have captured the spirit of a historic campus and allowed students past and present to discover anew the spaces, layers and details that oversaw learning and life within a cherished national institution. For their effort, the Bukit Timah Campus was named a Category A winner in the Architectural Heritage Awards (AHA) organised by the Urban Redevelopment Authority in 2012. This category recognises outstanding restoration projects involving National Monuments and fully conserved buildings in the historic districts.

Marcus Ng is Editor of BeMUSE.

Did You Know?

The Oei Tiong Ham Building, Manasseh Meyer Block and Eu Tong Sen Building were named after major donors to Raffles College. Oei Tiong Ham (1866-1924) was the Semarang-born ‘Sugar King of Java’ who moved to Singapore in 1920. He gave $150,000, then a princely sum, towards the construction of the central hall that now bears his name. Oei’s contribution was matched by Manasseh Meyer (1846-1930), a Jewish businessman and philanthropist who was also instrumental in building Singapore’s two synagogues. Eu Tong Sen (1877-1941), who gave $100,000, was a Penang-born entrepreneur who established himself in the tin business and traditional medicine (now the Eu Yan Sang company).