Text by Stefanie Tham

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 3 - Jan 2017

One gets a sense of both the local and the colonial when exploring Bukit Timah. From road names such as Princess of Wales Road and Jalan Haji Alias, to buildings like St Joseph’s Church, the former Ford Motor Factory and The Chinese High School, centuries of history can be found in Bukit Timah, each telling a part of Singapore’s past.

Remnants of Singapore’s colonial era can be found in the very road that traverses Bukit Timah today. In the early years after Sir Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a British trading port in 1819, the country’s interior was still relatively unexplored by the Europeans. Even though there were signs in the 1820s that indicated the presence of local settlers inland, the land beyond the Singapore River, such as Bukit Timah, was still deemed “wild and lawless” and these early inhabitants as “straying from the fold of civilisation”, quoting Sir James Brooke a naval officer stationed in Singapore in 1839.

Brooke’s evident bias reflected the colonial thinking of the time. Without access into the interior, it was impossible for the British to establish control over the land. As such, a long road weaving into Bukit Timah was constructed from the 1830s to 1840s, an attempt by the British authorities to impose some degree of colonial regulation over the unsurveyed interior. Part of this road is known contemporarily as Bukit Timah Road and Upper Bukit Timah Road. Completed in 1845, the road connected the northern tip of Singapore from Kranji to the heart of the city in the south, serving also as the main artery leading to neighbouring Johor.

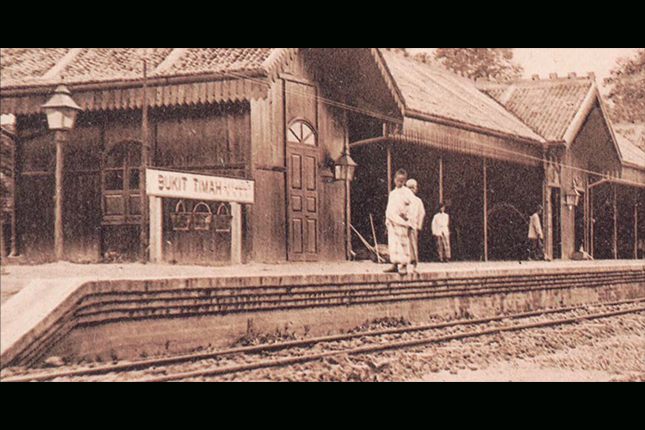

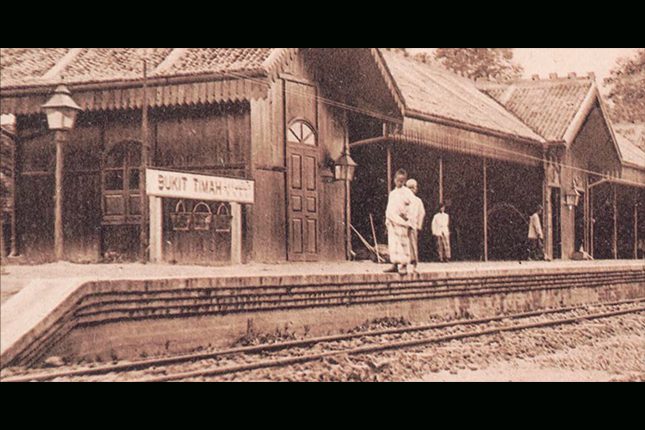

The road’s establishment precipitated a greater flow of people and commodities into the interior of Singapore. About half a century later in 1900, a railway line was being built to facilitate this movement. This railway line was later known as the Singapore-Johor Railway, and has become a shared memory among the subsequent generations of Singaporeans who remembered travelling to Malaysia via this railway.

As the interior opened, missionaries also ventured inwards to evangelise. French Missionary Fr Anatole Mauduit MEP purchased a parcel of land from the British East India Company to set up St Joseph’s Church between 1852 and 1853 at the 9 1⁄2 milestone along Upper Bukit Timah Road. Like many of the early Christian churches that owned tracts of land, the church parcelled out its land to parishioners to live and work. Over time, a network of institutions were built around St Joseph’s Church, including a trade school that would become Boys’ Town Singapore, serving the local community at Bukit Timah.

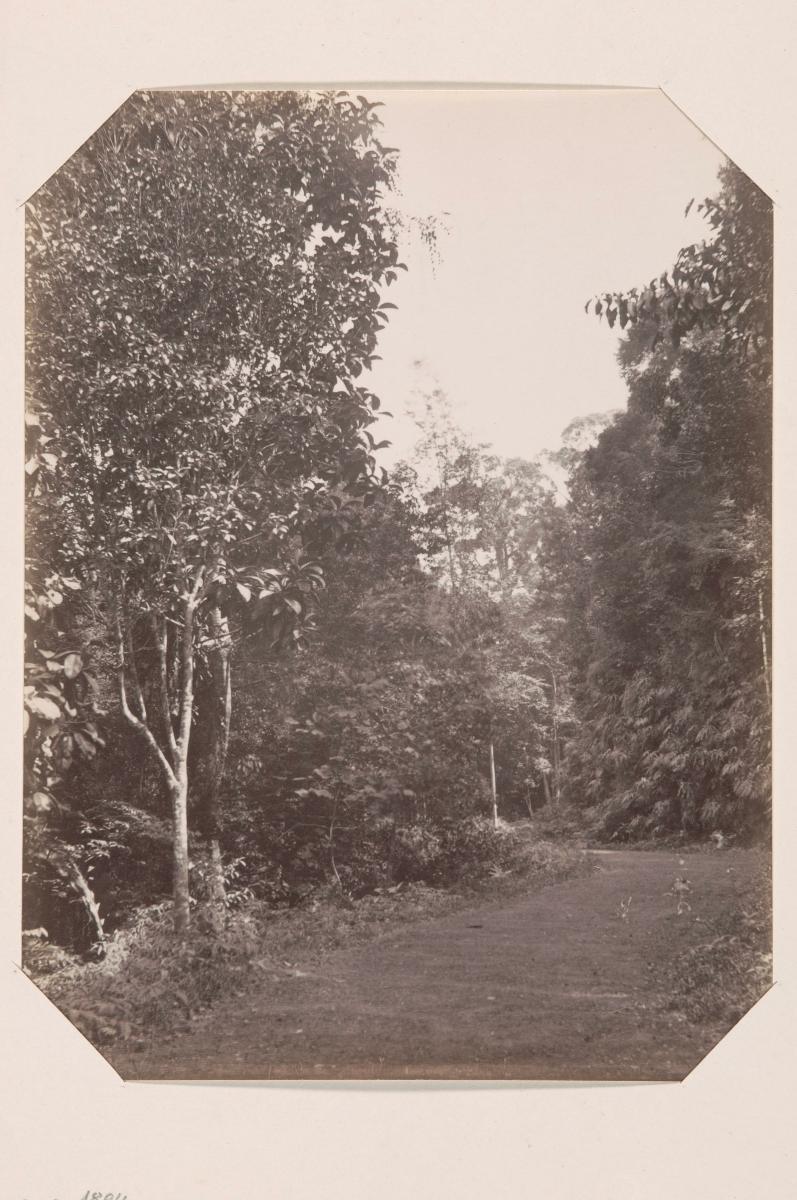

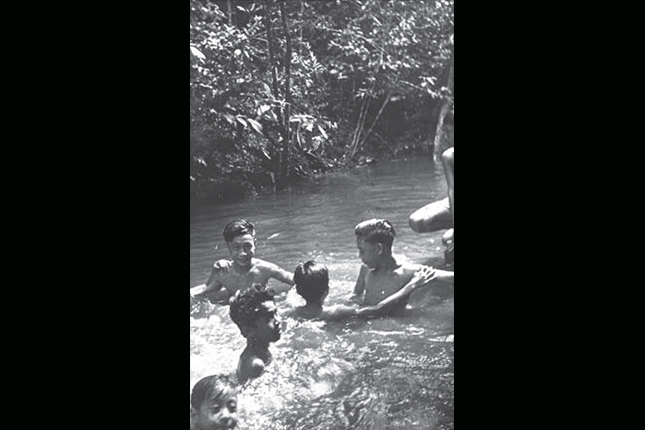

Bukit Timah Nature Reserve is arguably the most prominent landmark in the area. Standing at 163 metres high, the reserve is a sanctuary for many who seek reprieve from the hustle of the urban city today. The establishment of the reserve began in the 1840s, when the colonial authorities first made the hill a reserve. The area was recognised for its thriving ecology, with naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace extolling about the rich biodiversity found there after visiting Singapore in the 1850s. Wallace described the reserve in his book, The Malay Archipelago, saying, “[in] all my subsequent travels in the East I rarely if ever met with so productive a spot.” His observations in Bukit Timah also contributed to his eventual thesis on natural selection, conceived independently from Charles Darwin who also arrived at the same theory.

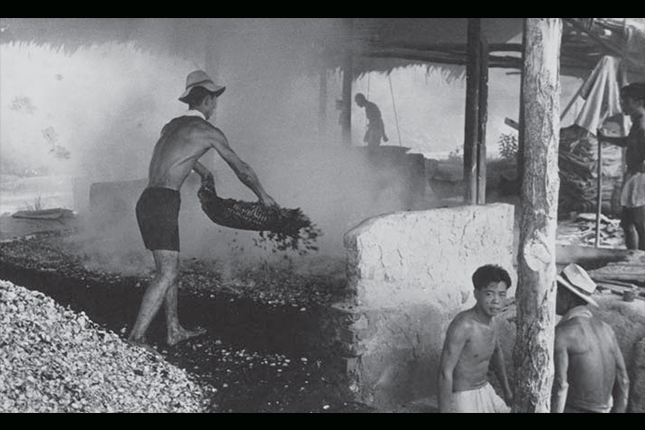

However, despite initial colonial efforts to prevent illegal timber harvesting and preserve the rainforest, poor management over the years depleted the hill’s primary forests. The granite quarries of the 1900s that are today incorporated into the reserve’s trails had further threatened the hill’s fragile ecology. Portions of the primary rainforest remaining today were saved in the 1930s by the efforts of Richard Eric Holttum, the director of the Botanic Gardens and his staff, including assistant director E. J. H. Corner and his assistant Mohammad Noor, who tried to lure away illegal woodcutters and throw their logging equipment away when they were distracted.

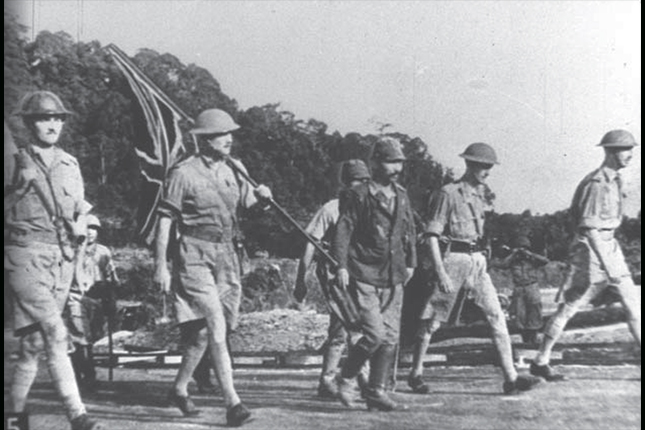

The serenity of the reserve today betrays the darker side of its history during the Second World War. The hill’s elevation made Bukit Timah an important target for the Japanese during the Second World War, providing a tactical vantage point that the invading troops wanted. Moreover, vital British supply dumps were stored in the area. At midnight of 10 February 1942, Japanese troops marched into Bukit Timah Village and by the following day, Bukit Timah hill fell into Japanese hands.

Another prominent site in Bukit Timah also featured significantly during the war. The former Ford Motor Factory along Upper Bukit Timah Road was converted into Lieutenant General Yamashita’s forward headquarters. It was at the factory where the terms of British surrender were discussed on February 15, 1942, a date that is still sombrely commemorated annually.

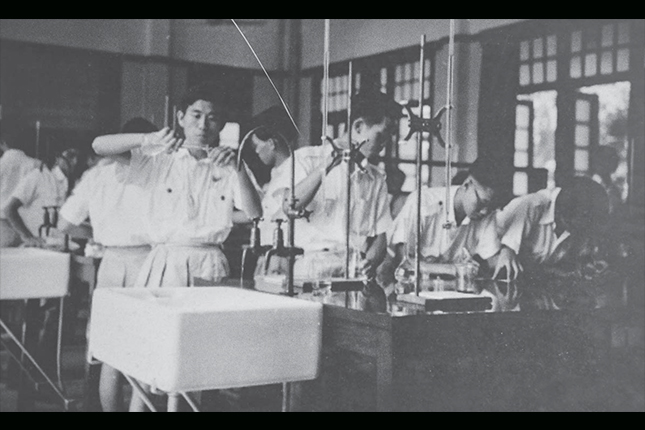

As the 1950s arrived, stirrings of early nationalism began to take hold in Singapore. Bukit Timah bore witness to this period of political awakening during the tumultuous decades of the 1950s and 1960s. Students from The Chinese High School were at the frontlines of several anti-colonial disputes, including the May 13, 1954 student protest over national conscription, which then saw about 2,000 Chinese High and Chung Cheng High School students staging a 22-day hunger strike against police violence in the following days. Students from the nearby University of Malaya (today’s National University of Singapore Bukit Timah Campus) also formed societies such as the University Socialist Club and Democratic Club to agitate for social and political causes during this period.

While these heritage sites reflect the more eventful moments in Singapore history, other places in Bukit Timah are remembered for being well-loved community spaces. Unsurprisingly, several of these spaces revolve around food, which is an unspoken shared pastime for Singaporeans. Some of these places draw Singaporeans from other parts of the island to Bukit Timah. The Adam Food Centre, for example, is one such popular food haunt. It started as a group of open-air stalls before moving to its current location opposite Serene Centre in 1974. Some of the stalls today, such as Bahrakath Mutton Soup King (stall No. 10) and Sathiyame Jeyam (stall No. 13), have been around since the early 1970s.

The rows of shophouses at Cheong Chin Nam Road and Chun Tin Road also offer a plethora of food choices. The latter street was named after Cheong Chun Tin, the first qualified dentist of Chinese descent in Singapore, whose son Chin Nam owned a rubber estate in the area. These roads grew popular from the 1990s, becoming well-known for restaurants that served halal Malay, Indian and Chinese dishes. Today, Korean and Chinese eateries can also be found there, offering even greater variety to the bustling lunch and dinner crowd.

Especially for the older generation, it is also not possible to speak of Bukit Timah without referring to the once-famous Beauty World, which started out as an amusement park during the Japanese Occupation and later converted into a marketplace in 1947. Unfortunately, Beauty World was destroyed by two large fires in 1975 and 1977, and subsequently redeveloped. Today, the Beauty World name is carried on by the shopping malls Beauty World Centre and Beauty World Plaza, both built in the 1980s and located across the road of the original market.

It is hard not to notice the number of schools that line the stretch of Bukit Timah Road. Bukit Timah is home to The Chinese High School, Nanyang Girls’ High School, Methodist Girls’ School, National Junior College and Pei Hwa Presbyterian Primary, to name a few. Pei Hwa Presbyterian is one of the oldest schools in Bukit Timah, founded by the Chinese Christian Church (now Glory Presbyterian Church) in 1889.

For many of these students who went to school in the area in the 1990s, the former McDonald’s Place at King Albert Park would have been one of the choice places in Bukit Timah to hang out after class. The spacious two-storey branch opened in 1991 as the biggest McDonald’s outlet in Singapore, and also housed the restaurant’s corporate headquarters and a staff training centre. Students and residents alike have incorporated their visits to the restaurant as part of their daily routine. “We would have lunch, read books, study and enjoy the air-con,” David Lim, a former Nan Hua Secondary alumnus remembers. Some students would park themselves on one of the 433 seats daily to study during the examination period. It is also very common for residents to visit the outlet for breakfast on Saturday mornings. Although the outlet closed in 2014, these memories live on among the generations of students who studied in Bukit Timah.

Bukit Timah is one of the areas that witnessed the Japanese invasion during World War II, and was also where the British surrendered on 15 February 1942, marking the start of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. These sites of World War II are featured in the Bukit Timah Heritage Trail, one of the 17 trails offered by the National Heritage Board as of 2016. The trails can be downloaded at the NHB portal here.