TL;DR

This article looks at a number of monuments where wartime events took place at different stages of Singapore’s history as Syonan-to, and how they now serve as landmarks of memories in the country’s ever-changing landscape.

Text by Foo Min Li

Be Muse Volume 5 Issue 1 – Jan to Mar 2012

On 15 February 1942, Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival and three other officers walked to the Ford Factory. At the factory, they met with General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Japanese Imperial Army to sign the surrender document.

National Museum of Singapore Collection.

Located in Upper Bukit Timah Road, the factory was Ford’s first motorcar assembly plant in Southeast Asia, completed just the year before. General Yamashita took over the premise and turned it into a Japanese headquarters, where he awaited Lieutenant-General Percival’s arrival on the morning of 15 February 1942. The factory formed the setting for the British surrender, which marked the start of the Japanese Occupation that lasted three years and seven months.

Today, the Ford Factory is one of Singapore’s national monuments. These national monuments are gazetted for their architectural and historic significance. While Singapore’s monuments are in pristine condition today, they too have witnessed the country’s darker moments as Syonan-to.

This article looks at a number of monuments where wartime events took place at different stages of Singapore’s history as Syonan-to, and how they now serve as landmarks of memories in the country’s ever-changing landscape.

Lead-up to the fall of Singapore

Just two months before the fall of Singapore, the Japanese struck seven locations in the Asia-Pacific region during the wee hours of 8 December 1941, including Singapore. Maurice Baker, who was a student at the Raffles College then, recalled that he was awakened in his hostel by bomb explosions, anti-aircraft guns and sirens from the air-raid alarm. Shortly thereafter, he and his classmates received news from his principal, Professor of History W. E. Dyer, that war in the Pacific had started and Japanese airplanes would strike again. Notwithstanding the grim future, Professor Dyer urged his students to act with great compassion towards the less fortunate. Together, they organised the Raffles College Medical Auxiliary Service, bringing medical volunteers to serve in disaster areas while the college became a makeshift hospital for the wounded.

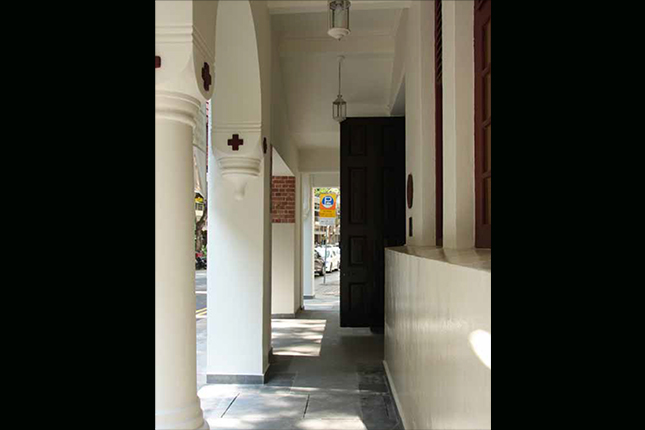

Raffles College was one of the buildings that were used for new purposes during wartime to serve people in that time of need, and Professor Dyer’s spirit of compassion was echoed elsewhere. As air raids intensified and soldiers started retreating from Malaya into Singapore, several other makeshift hospitals emerged to help existing hospitals cope with the increasing number of wounded. Such makeshift hospitals in the city included the St Andrew’s Cathedral, Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall and the St Joseph’s Institution. While these buildings were not designed to house hospital beds and operating theatres, the medical volunteers made do with the spaces and replaced the existing furniture, swiftly transforming them into hospitals. Today, although pews have long since replaced the beds at St Andrew’s Cathedral, history is memorialised in the plaques dedicated to servicemen who perished in the Second World War, as well as the First. The extension of the church’s north transept in 1952 also became known as the War Memorial Wing.

Nearby, one of Singapore’s biggest pre-war structures, the Municipal Building (the former City Hall), took in people who needed shelter from the ongoing air raids8. Constructed between 1926 and 1929, the building was designed with a long frontage made up of 18 colossal columns. This was to reflect the colonial rule’s strength and the Municipal Council’s important functions, which had expanded significantly in the 1920s. During air raids, the building’s large size and thick walls could provide people with adequate protection from the blasts. The Municipal Council recognised this, and also created additional shelter for another 150 people within the building by cutting into the rear of the building’s main stairway facing St Andrew’s Road.

People also sought shelter and solace in places of worship amid the chaos. These places provided both spiritual help and physical protection to the people, who held on to the hope that Japanese troops would not wreak havoc in these religious places and they would hence be safe. In fact, Japanese troops did receive instructions to leave religious organisations alone. In Kampong Glam, people who lived in villages around the Sultan Mosque – both Malays and non-Malays – fled to the mosque during air raids and prayed for safety there. Venerable Pu Liang opened the doors of Siong Lim Monastery in Toa Payoh, the largest monastery in Singapore and Malaya at that time, to people living in the vicinity during air raids. Likewise, Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church also served as a medical centre and bomb shelter. Its exterior walls facing the street were thickened and reinforced to prevent shrapnel from penetrating the church, providing protection to the wounded and others hiding there. In addition, it had a trapdoor located in its social hall, leading to a hideout where British soldiers hid when they tried to escape from Japanese troops.

Image by Preservation of Monuments Board, 2010.

Some places of worship, however, could not escape the damage and harm caused by war. For instance, the Sultan Mosque was not always trouble-free. A bomb had fallen into its compound during an air raid, damaging one of its ancillary buildings.

National Museum of Singapore collection.

Although the Japanese troops had been instructed to leave religious organisations alone, they still entered Siong Lim Monastery to capture Venerable Pu Liang and a few of his disciples in 1942, for they were keen supporters of the anti-Japanese resistance movement. Venerable Pu Liang, who came to Singapore in 1921, condemned the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and fiercely supported the anti-Japanese movement. In the late-1930s, he donated Siong Lim Monastery’s Vesak Day monetary collection to the China Relief Fund. As the monastery’s premises were huge and Japanese troops were not supposed to enter this place of worship, anti-Japanese groups had secretly conducted trainings in the monastery. Specifically, Venerable Pu Liang permitted Allied troops to train their pilots and technicians there. He also allowed a training centre to be set up to train drivers and mechanics to ply the treacherous Burma Road into China, so as to maintain supplies for the Chinese troops. His support for the anti-Japanese movement was too great for the Japanese to ignore, resulting in his arrest in 1942.

On the morning of 15 February 1942, Lieutenant-General Percival and other Anglicans attended communion service at St Andrew’s Cathedral before he surrendered Singapore to the Japanese. The cathedral remained open for service throughout the Japanese Occupation, and its membership grew with more converts in that period.

Years of fear: 16 February 1942 – 12 September 1945

While people in Singapore created new purposes for existing buildings to protect lives, the Japanese occupied some of the country’s key buildings and converted them into spaces that evoked public fear. The kempeitai (military police) were housed in these buildings to keep a close watch on the people. For instance, the Hill Street Police Station built between 1934 and 1936 as a police station and barracks for the police force to ensure order in Singapore, became one of the kempeitai offices where the military police committed atrocities and tortured their victims.

The Japanese also used the former Cathay Building, which opened as Singapore’s first air-conditioned cinema in 1939, as an outlet for Japanese propaganda. Japanese movies and propaganda films were screened in the theatres, with rare treats of German and Italian films. As the building was designed to house offices and apartments, it was a suitable venue for the Japanese Propaganda Department, which was also the media centre for all newspapers in Singapore and Malaya. Given its prime location as a cinema which attracted movie-goers, Cathay Building and its surroundings became a good spot for the Japanese to display severed heads of looters and thieves to strike fear in people.

Rudy Mosbergen, a 13-year-old student then, was one witness of this gory scene:

"As a little boy I heard some people talking down there, they said, you know if you go to Cathay Building, there is a head chopped off. I went down to Bras Basah Road, next to Hotel Rendezvous now. And from there I could see, I looked across next to the Cathay Building, there was a table and that fellow’s head was there."

Education was disrupted. Schools were either shut down or became tools of propaganda for the Japanese. Raffles College, one of the two tertiary institutions at that time, became a medical facility and later the headquarters of the Japanese military. Chinese schools such as Tao Nan School (which houses the Peranakan Museum today) stopped functioning during the Japanese Occupation. They were targeted by the Japanese as they had supported the anti-Japanese movement, and the premises were occupied by the Japanese army. Ng Kim Hua, a student of Tao Nan School then, recounted that the Nationalists had visited Chinese schools in Singapore to recruit young men for China’s battle against the Japanese. Lin Shiping, who taught at Tao Nan School from 1939 to 1942, shared that several teachers went into hiding after the Japanese occupied Singapore in 1942. His colleagues, Wang Zhixue and Xue Fanglun, were caught and killed.

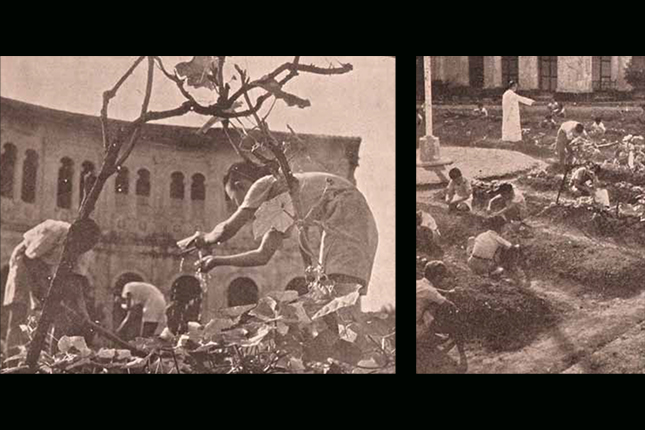

English schools such as St Joseph’s Institution, on the other hand, were more fortunate. They were allowed to continue functioning to serve the needs of the Japanese. St Joseph’s Institution reopened as the Bras Basah Boys’ School after serving as the Red Cross Hospital. The students’ daily tasks, however, included growing crops in the green space in front of the school during lesson time, so as to support the “Grow Your Own Food Campaign”. The Japanese implemented this self-sustaining policy as food was becoming increasingly scarce.

Source of archival photograph: Wong Hong Suen

The Japanese Surrender and Singapore's Independence 20 Years Thereafter

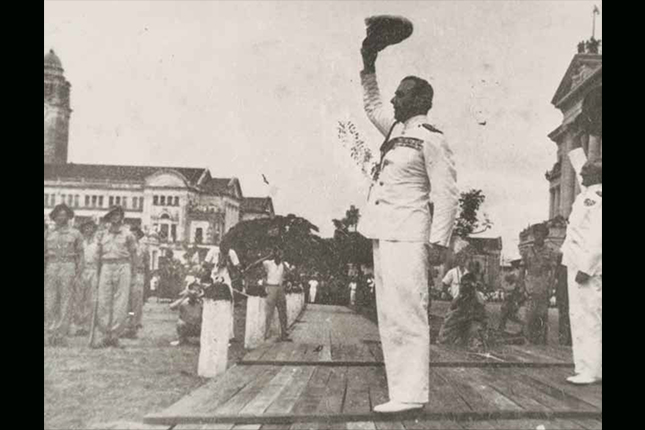

The difficult lives experienced by people during the Japanese Occupation finally ended on 12 September 1945 with the Japanese surrender and the end of the Second World War. While Ford Factory witnessed the beginning of the Japanese Occupation on 15 February 1942, the Municipal Building celebrated its end on 12 September 1945. This joyous occasion was widely reported in The Straits Times, marking the paper’s revival after it stopped operating on 15 February 1942. People gathered around the Municipal Building to witness the Japanese’s march to surrender.

Spectators planted themselves at vantage points – including the base of the dome of the former Supreme Court and the roof of the Municipal Building – to witness this historic moment. The Straits Times report, “Japanese in Malaysia Surrender at Singapore” dated 13 September 19452, described this momentous event:

"All vantage points had their large or small groups of spectators. Any roof within was packed with Chinese, Malays and Indians determined to see this historic ceremony."

"Scene of so many important civic meetings which had produced decisions leading to the great development of Singapore in the old era, the Municipal Council chamber yesterday became a stage for a drama of the greatest historical importance."

This important event began with a formal ceremony at the Padang, followed by the solemn proceedings in the surrender chamber. Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, inspected the parade at the Padang.

National Museum of Singapore collection.

Mosquito bombers” – British combat aircrafts – flew over in salute, big Sunderland flying boats used in long-range reconnaissance and bombing missions droned over, which were then followed by Dakota transports. The Japanese representatives arrived shortly thereafter and proceeded to the Municipal Building where they waited to sign the surrender document, witnessed by several individuals including the Sultan of Johore. He shared:

"I have never before been so stirred. I am glad to have been there to watch these fellows sign. I am proud to have had the honour of witnessing their formal surrender."

In a matter of nine minutes, the Japanese officially surrendered, and the surrender was publicly declared by Lord Louis Mountbatten on the steps of the Municipal Building.

National Museum of Singapore collection.

Twenty years later in 1965, then-Premier Lee Kuan Yew broke the news of Singapore's separation from Malaysia to some heads of consulates and key civil servants in the City Hall building (renamed from Municipal Building in 1951).

The Municipal Building has thus witnessed Singapore’s transformation from colonial rule, to subjugation to the Japanese, to independence.

Remembering: Monuments and Memories

Many years on, people’s bravery and actions are remembered through stories and memorials. For instance, the iconic block with the clock tower of the Singapore General Hospital was renamed Bowyer Block in memory of John Herbert Bowyer, Chief Medical Officer of the Outram Road General Hospital. Bowyer died in Sime Road Internment Camp during the Japanese Occupation on 1 November 1944. Also, just across the Padang facing the Municipal Building stand two memorials. One is the Cenotaph, built to commemorate the war dead; while the other is the Lim Bo Seng Memorial to honour an individual.

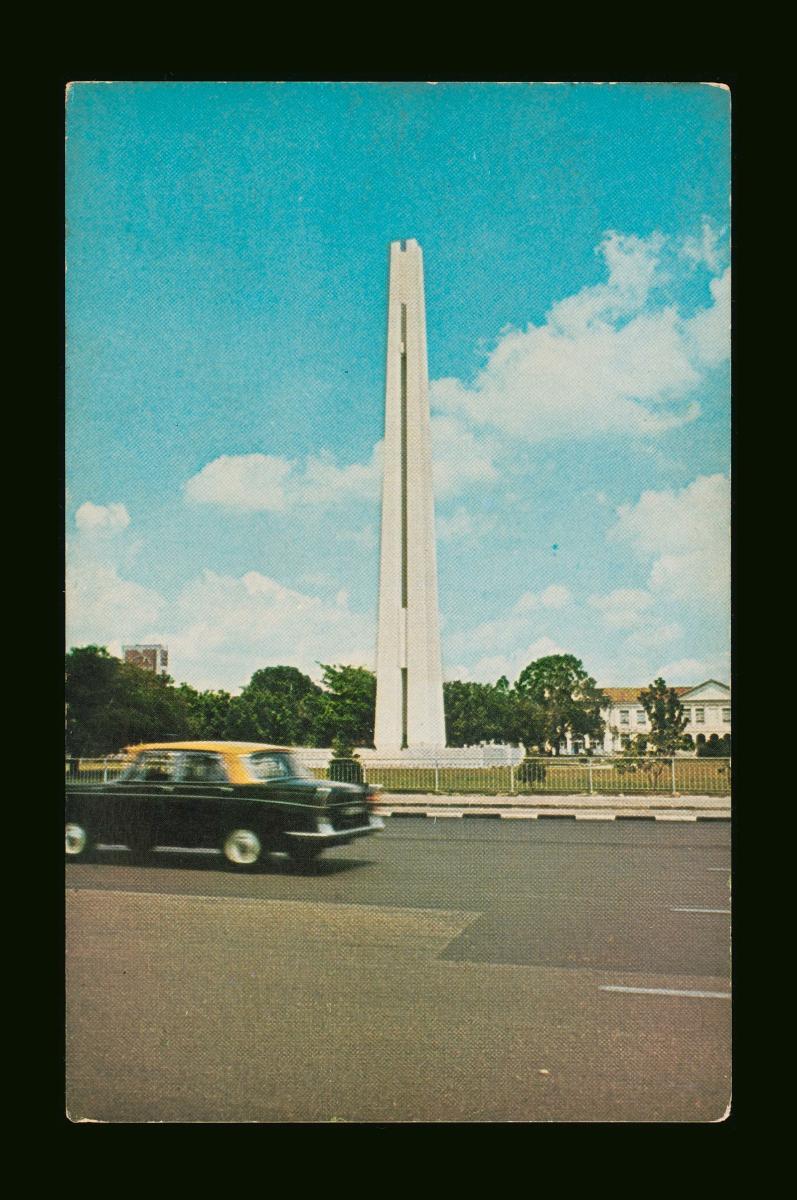

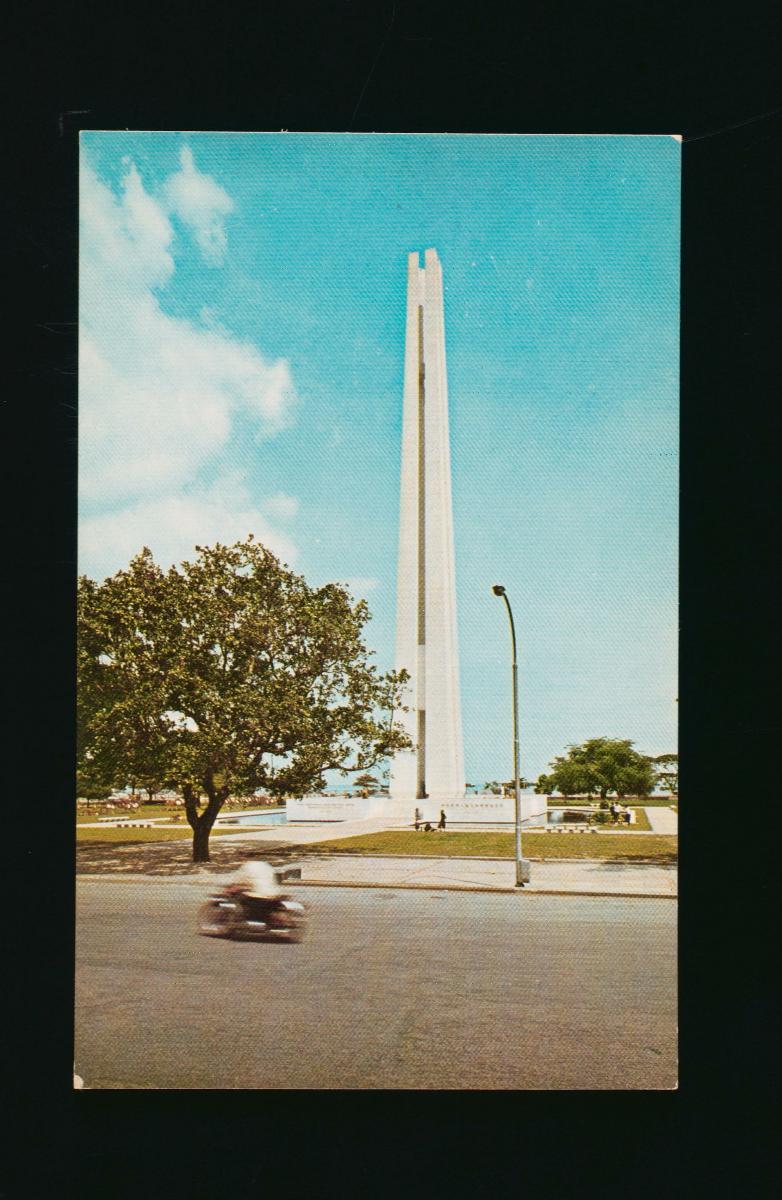

Images by Preservation of Monuments Board, 2011.

The Cenotaph, unveiled on 31 March 1922 by the Prince of Wales, was erected in honour of the 124 men from Singapore who died in action during World War I. A second dedication was made between 1950 and 1951 to those who died during World War II. Unlike the first dedication, the second did not have any names because the number of war dead was overwhelming. Instead, the message “They died so we might live” was inscribed.

Just beside the Cenotaph, the Lim Bo Seng Memorial was dedicated to Lim Bo Seng, a man who assumed leadership for anti-Japanese activities during the Second World War. Unfortunately, he perished on 29 June 1944 following his capture by the Japanese at a road checkpoint. The construction of the memorial faced much challenges as the plans for the memorial were rejected at least five times by the government. Under the Memorial Committee’s perseverance, it was finally constructed and unveiled on 29 June 1954, a decade after Lim’s passing. The committee persisted probably because it wanted future generations to know and remember the story of Lim, who could also represent other unnamed individuals who had sacrificed themselves for Singapore’s freedom.

Foo Min Li is Manager, Preservation of Monuments Board