Text by Low Zu Boon

Images courtesy of Puan Sri Datin Dr Rohana Zubir

Be Muse Volume 5 Issue 4 – Oct to Dec 2012

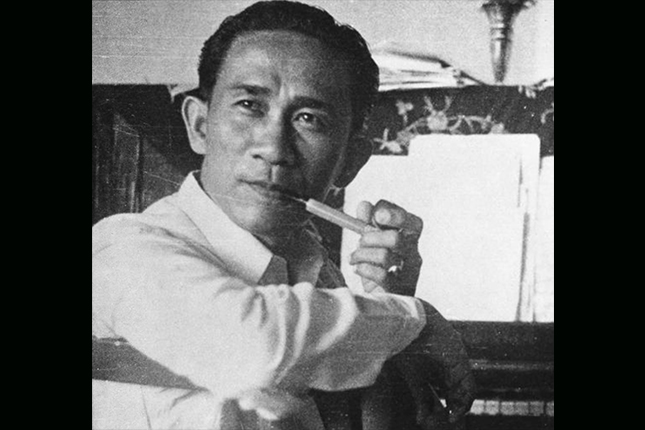

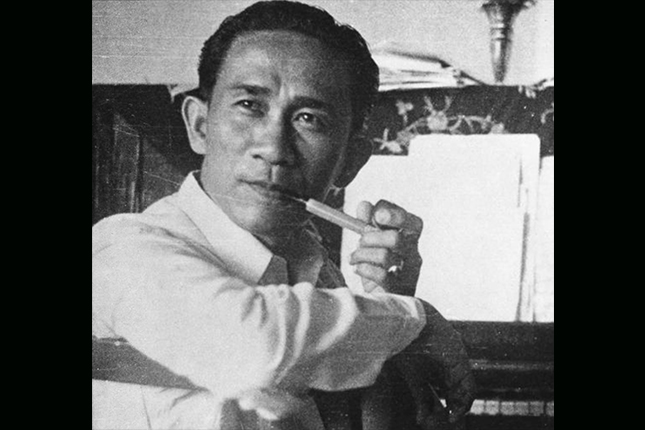

Zubir Said, also affectionately known as Pak Zubir, is most well known as the composer of Singapore’s national anthem, Majulah Singapura. In an institutional sense, the acceptance of the song as the national anthem, and its first performance at the ‘Loyalty Week’ on 3 December 1959, marked the peak of Pak Zubir’s career in music1. This was at a stage of his life when he was deeply engaged in composing ‘patriotic’ songs as an expression of his belief that one should pay tribute to the nation in which one lives in. However, his identity as the anthem’s composer tends to overshadow the fullness of his life, which was filled with a ceaseless exploratory spirit and a sense of adventure that gave rise to many creative endeavours and hundreds of songs which now resonate throughout the archipelago.

It is a little known fact that Pak Zubir was an influential figure within the rise of what we now affectionately call the golden age of Singapore cinema in the late 1940s to 1960s. Perhaps, this is due to an auteuristic tendency in film spectatorship which endows utmost emphasis on the creativity of the director, and the star-system which casts a glamorous spotlight on actors and actresses. However, filmmaking during the golden era was more than the sum of its directors and acting talents. It was a collective act of creative production that brought into play scriptwriters, set designers, playback singers, and of course, composers who imbued the screen images with the affects of songs and soundscapes, and inscribed links between film and music cultures.

Music was an essential aspect of our films from the golden age. The pioneering wave of directors in Singapore in the 1940s and 1950s, such as B. S. Rajhans and B. N. Rao, brought with them stylistic traits of Indian cinema. These included the convention of having a series of song sequences throughout the film which acted as aphorisms that propelled the narrative and encapsulated the emotions and sensations expressed in the film through verse and melody. This proved to be a popular trait which audiences came to expect, and it became an inherent construct within our cinema heritage. It was within this milieu and aspect of filmmaking in which Pak Zubir emerged as a pioneering music composer in Singapore who had brought forth many innovations and humble revolutions to the role of music in film and Singapore society.

Pak Zubir’s pioneering ethos in music composition was a clear expression of a strong will towards independence and living on one’s own terms. He was born into a Minangkabau family on 22 July 1907 in Bukit Tinggi, West Sumatra. His father, Muhamad Said Sanang, a well respected village headman, strongly opposed his son’s musical aspirations as he felt that music was harum (prohibited in Islam)2. As such, Pak Zubir never received a formal education in music. However, he retained a strong fascination towards music, and learnt his musical skills from different communities and individuals. In school, Pak Zubir learnt to read and write the solmisasi system of numerical musical notation. He also learnt to play drums and guitar from a keroncong club3. Upon graduation, Pak Zubir played with the village keroncong orchestra, and learnt to play the violin from a musician who performed music accompaniment at a silent film cinema. Soon after, he quit his day job at the Dutch administration office to join a keroncong troupe which travelled around Sumatra.

Pak Zubir was 22 years old when he accepted a sailor friend’s offer to journey to Singapore on a small cargo boat, only bringing with him a clean towel, a few shirts and a small amount of money, which was all that he had. In Minangkabau tradition, it is a rite of passage for young men to experience merantau, to travel out of their home environment to seek their fortune. After travelling through Sumatra, Pak Zubir’s wanderlust extended towards the archipelago, and he had to experience Singapore, the thriving entrepôt which he came to know as a place of electricity, and kopi susu and butter – both of which he had never tasted before. Peering out from the cargo boat, Pak Zubir caught his first sight of Singapore when he arrived in the wee hours of the morning. He was wholly fascinated by the bright lights glimmering from the island that he would soon call home.

Recalling his early experience of Singapore, Pak Zubir emphasised the exalting feeling of freedom and cultural diversity of its society. He started his first job as a pianist and violinist for the City Opera, a large bangsawan troupe that staged performances at Happy Valley Park in Tanjong Pagar4. There he met Malay, Straits-born Chinese (Peranakan), Indian and Filipino musicians who worked collectively to perform a repertoire of songs which featured Malay, Chinese and Indian stories. Already skilled in number notation, Pak Zubir rapidly mastered staff notation, copied all the troupe’s scores in both systems, and soon became the leader of the ensemble. He was recruited by The Gramophone Company (commonly known as His Master’s Voice) thereafter, where he worked as a recording supervisor who also travelled through Malaysia and Indonesia as a talent scout.

1948 marked the year when Pak Zubir stepped into the arching gates of the golden age of Singapore cinema. Helmed by the two major studios, Shaw Brother’s Malay Film Productions and Cathay-Keris Films, this was the era of the post-war studio system which reached a combined average output of 15 to 20 films annually.

Pak Zubir was introduced to the chief of Malay Film Productions, Shaw Bee Hock, who recruited him as a freelance composer over at their studio in Jalan Ampas. The first film he worked on was Chinta (1948, B. S. Rajhans), which starred Siput Sarawak and S. Roomai Noor as lovers star-crossed by the tussles of previous generations. As not all screen actors could sing, Pak Zubir brought in the practice of voice-dubbing and recruited Nona Aishah and P. Ramlee, who also starred in his first ever screen role, to perform as playback singers. Another Shaw film Pak Zubir had worked on was Rachun Dunia (1950, B. S. Rajhans), a modern melodrama which featured one of his most celebrated compositions, Sayang Di Sayang.

Pak Zubir, however, felt that musical composition could be developed further. He believed that the musical palette for a motion picture should not be contained within the songs, but should be used effectively to convey the array of emotions throughout the film. During its early days of production, Malay Film Productions had a practice of using pre-recorded tracks for background music. Sensing greater opportunities for creativity, Pak Zubir subsequently joined Cathay-Keris Films as a full-time composer of both film songs and background music. There he composed songs and background music for some of the most highly regarded films which are now part of our heritage, such as Sumpah Pontianak (1958, B. N. Rao), Dang Anom (1962, Hussain Haniff ) which won the award for Best Folk Songs and Dances at the ninth Asian Film Festival, and Chu- chu Datok Merah (1963, M. Amin).

Pak Zubir was the first composer in Singapore to create original background music specifically for films. While songs were composed prior to, or during the film shoot, background music was created after the film was completed. Pak Zubir would start with a central melody which he then expanded into different styles and variations according to the changing moods and character motifs in the film. As he had to work with an average of only eight musicians when film music generally needed a larger orchestra, Pak Zubir had to experiment to create a grand effect with the little that he had.

In composing music for Malay films, Pak Zubir encountered two hurdles. Firstly, he felt that it was limiting to draw only from the repertoire and traditions of Malay music as they generally contained only two contrasting moods, happy and sad, while films contained a diversity of emotions. Secondly, Pak Zubir was acutely aware of the homogenising effects of the burgeoning commercialisation of popular music, which he saw as detrimental towards the development of a wider spectrum of music that “adds to the richness of the form of music within every nation.” As a creative escape from these two constraints, Pak Zubir continued to look to his Minangkabau heritage, conjuring the sounds of keroncong and bangsawan, while innovatively and self-reflexively infusing a wide array of cultural notes, which included styles such as Malay asli, Indian raga tala, and even Hawaiian, Arabic and Filipino sounds.

As a composer, Pak Zubir cherished authenticity and originality. He felt that the “state of independence achieved by a nation is greatly connected to the heritage and culture of that nation,” and strove to reflect the mindset of his time through diverse forms of music that could be easily understood and appreciated beyond entertainment purposes. From the mid-1950s, while he was still working at Cathay-Keris, he had begun to write ‘patriotic’ songs such as Semoga Bahagia, Hari Kemerdekaan and, of course, Majulah Singapura, all of which are timeless and cherished communal musical expressions of our nation. For his film music compositions, we witness the same motivations at work, but within certain entanglements which he strove to loosen. It cannot be ignored that the film industry is a commercial vehicle aimed at the masses. In Pak Zubir’s film music compositions, we sense the critical drive of a composer striving to express the soul and the culture of the community within an entertainment medium. With modernity, Western influences have been shaping and changing the contours of local music forms. When Pak Zubir had to reflect these influences in tune with filmic narratives, he had thought deeply on how they could be appropriated in a way that would still allow the heart of Malay music to resonate down in history.

Throughout his life, Pak Zubir continued to utilise number notation to compose music, and spent his later years teaching it to the younger generation at his apartment in Joo Chiat Road. He did so not only because it is the most common method of documenting Malay traditional music, but also because of its simplicity. He saw the system as building blocks which anyone with an interest in music could utilise to participate in the creation of diverse forms of musical expression. On top of the many songs Pak Zubir contributed to our nation, his view of the relation between music and nation building has imparted an important lesson to all of us: the significance of music as an expression of the common thread and ideals of the community, and the joyfulness of a democratic drive in which everyone in the community has the means to participate in the creation of the arts and culture of the nation.

In Pak Zubir’s lifetime, the brimming bright lights of Singapore, which he saw from the small cargo boat when he first arrived, had led him to become a bearer of the constellation of lights and sounds of the golden age of Singapore cinema. This constellation of lights and sounds continues to brighten the darkness of our cinema halls today. For Pak Zubir, it started with a fascination which led to an adventure. It is with this sense and feeling that he had composed his music and imagined the future of the nation.

Low Zu Boon is Assistant Manager (Programmes), National Museum of Singapore.

Notes

References