Text by Alan Chong

Images courtesy of Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Centre

BeMuse Volume 4 Issue 3 – Jul to Sep 2011

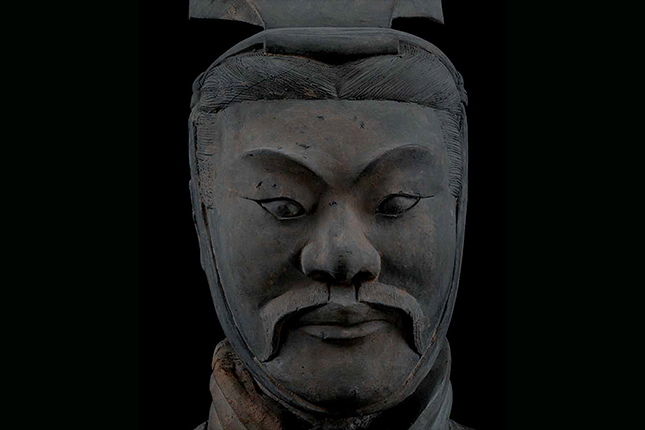

The terracotta warriors of China’s First Emperor, or Shi Huangdi, have drawn worldwide attention since their chance discovery outside Xi’an in 1974. They impress with their life-like appearance, the evident attention to detail and the fact that there are so many of them. To date in 2011, about 1,900 have been unearthed, but there may be as many as 8,000 figures all together. Investigation of the vast tomb complex of the First Emperor continues and new discoveries await. The terracotta warriors have been exhibited around the globe and have become worldwide celebrities. But they are more than just spectacle – they tell us a great deal about history and art.

The terracotta warriors are connected with one of the most remarkable – and controversial – figures in China’s history: the king of Qin who united China in 220 BCE and became the First Emperor. He invented for himself a new title, Huangdi, based on two words to describe mythical kings, and all emperors after him used the same title. He centralised authority and attempted to unify China by standardising her money, writing and measurements. However, after his death, he was condemned as corrupt, militaristic and despotic. He is alleged to have buried Confucian scholars alive and burned their books. And he built a grandiose tomb to himself that supposedly required the efforts of 700,000 workers.

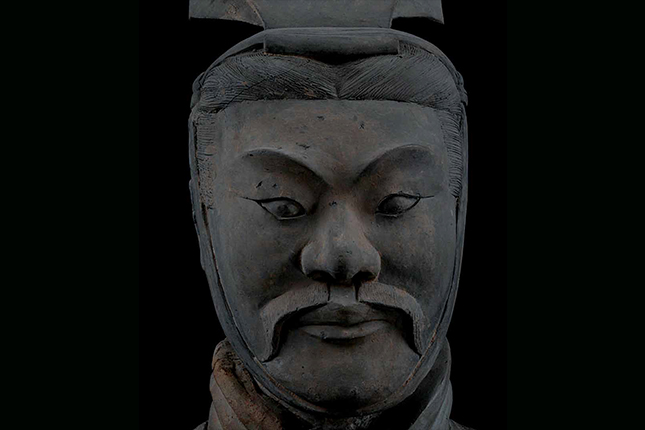

Beyond this historical connection, the terracotta warriors are intriguing works of art that completely changed long-held beliefs about early Chinese art. Before the discovery of the terracotta warriors, nearly nothing was known about the art of the Qin dynasty, which was one of the pivot points in Chinese history. While the terracotta army confirmed the emperor’s militaristic reputation, the figures themselves seemed to be the product of a cultured and sophisticated court. Often thought to be portraits of individual warriors, on close inspection, the figures repeat a few basic types. Details of armour, costume and footwear vary within certain patterns, and the faces seem to have individual personalities because six or eight different moulds were used; beards, moustaches, hair and other details were later added. Some soldiers were shaped to hold weapons or the reins of horses. Other figures seem to stand at attention.

The warriors present us with many mysteries and we cannot be certain of their precise meaning. They look real, but can we be sure that they accurately reflect Chinese soldiers of 2,200 years ago? The terracotta figures are not documents, but works of art made to decorate the First Emperor’s tomb. They therefore had powerful symbolic value. Are they a legion of the emperor’s army or his palace guard? We might assume that the warriors were meant to defend the emperor in the afterlife, but against what?

It is sobering to realise that the terracotta warriors, magnificent though they are, are only one part of a vast supporting structure of the First Emperor’s tomb. The terracotta figures are divided among three pits. The largest contains more than 6,000 infantry, archers and commanders, plus fifty chariots, each drawn by four horses.

Pit 2 is smaller but contains more horses: 89 chariots, with four horses apiece, 116 horses with riders and additional infantry.

The smallest pit, Pit 3, contains a single chariot and 68 warriors. A fourth pit is empty.

The emperor’s tomb is buried under a large, man-made, pyramidal hill. It is protected by mountains to the south and west, and water to the north. The terracotta warriors all face east. The tomb mound was surrounded by two walls that enclosed several buildings devoted to the rituals worshipping the deceased emperor. Surrounding the tomb were numerous pits, some containing actual human and animal remains.

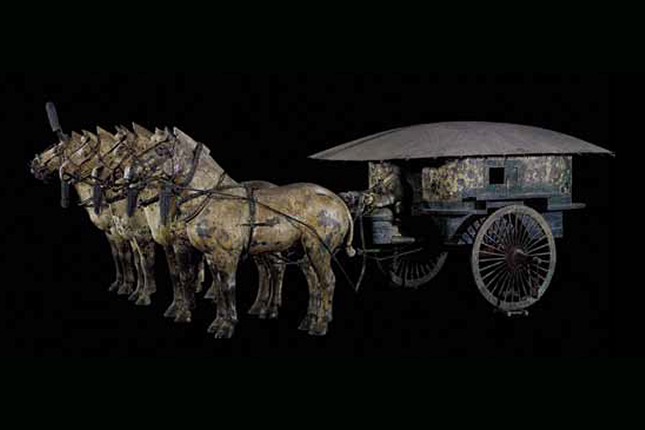

Several half life-size chariots were buried very near the tomb. Wooden chariots ornamented with bronze and gold fittings were found on the north side, while to the west were the two famous bronze chariots, drawn by miniature bronze horses.

A pit containing thousands of small stone plaques was discovered in 1999. Eventually, someone realised that they used to form sets of armour. Because limestone is too heavy and too fragile to have been used in battle, the armour must have played a purely symbolic role. But we do not know who was meant to wear this symbolic armour.

Other discoveries show that the tomb world of the First Emperor was not only devoted to the military. Workers were buried near the tomb along with horses and other animals – demonstrating that human and animal sacrifice, conducted in China for thousands of years, was still a part of imperial funerary practice. And twelve pottery officials were found huddled together in a small pit, ensuring that bureaucracy would live on with the emperor.

Another pit contained eleven life-size terracotta figures different from the warriors. These were bare-chested men in various animated poses. Compared to the blank expressions and stiff postures of the warriors, these acrobats are much livelier and even humorous, features that have no precedent in Chinese art. One heavily muscled figure, perhaps a weightlifter, has bulging biceps, a barrel chest and a thick belly supported by a wide belt. He must have originally held something against his body with his left arm, perhaps a pole. Together with his companions, he entertained the emperor at court.

Yet another pit housed musicians made of terracotta and birds made of bronze. Forty-six swans, geese, and cranes were neatly arranged along an artificial river of mercury. Near the water birds were fifteen musicians, which suggests that this venue was for relaxation and pleasure. Another pit contains the remains of exotic animals, perhaps a zoo to delight the emperor.

Taken as a whole, these discoveries show that many aspects of the emperor's life were recreated in underground burials. But any interpretation of the terracotta warriors remains tentative without knowledge of the tomb itself – the underground palace that houses the emperor's coffin. No excavations have yet been conducted there, but further discoveries are sure to come.

We can speculate as to the meaning of the terracotta warriors. They may have been commemorative, that is, a celebration of the military power that unified China. Although the tomb was started when the First Emperor was still king of the Qin state, plans must have expanded significantly when he became emperor. The warriors undoubtedly played a protective role against evil forces (as similar figures had in earlier tombs), perhaps against the spirits of old enemies to the east. The army also appears to be a component of the emperor's worldly life made in symbolic form for the afterlife. It is very likely that the terracotta army had multiple meanings, and we should be open to new avenues of interpretation.

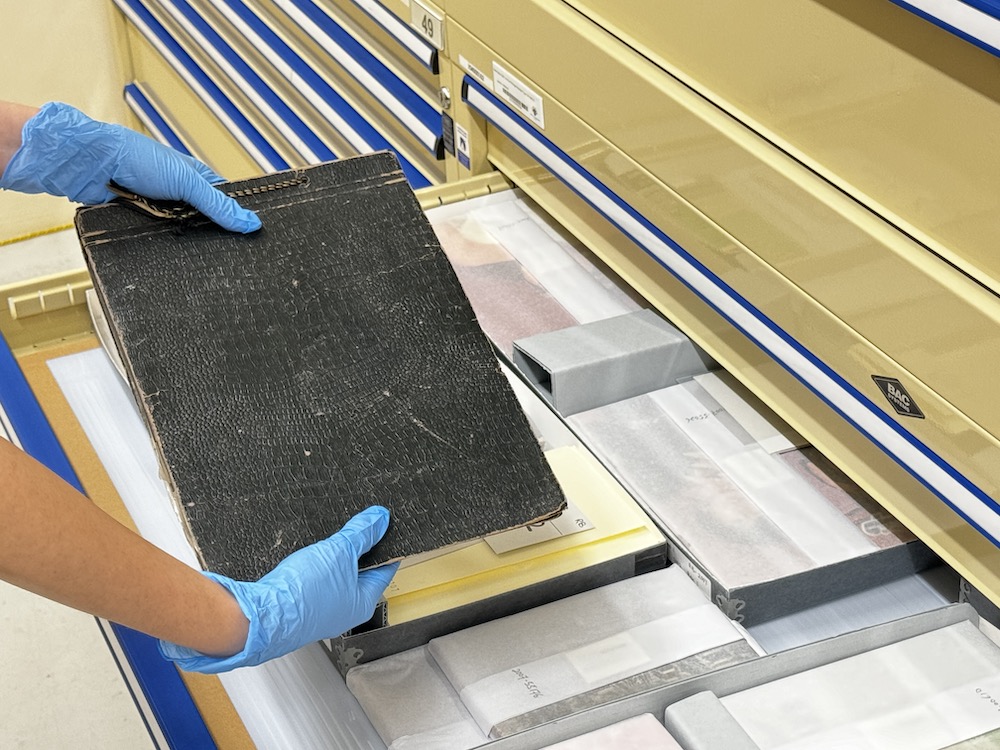

The terracotta sculptures have radically altered our understanding of early Chinese art. Despite the overwhelming historical importance of Shi Huangdi, almost nothing could be associated with his reign. Objects from the Shang and Zhou dynasties had been greatly appreciated for their abstract patterns and decorative designs especially bronze vessels. At the exhibition Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor and His Legacy, the Asian Civilisations Museum showcased a range of goods buried in Qin state tombs before the reign of the First Emperor. These included ritual bronzes, jades and gold objects.

The Han Dynasty

The Qin dynasty quickly collapsed after the death of the First Emperor. After a period of civil war, Liu Bang established the Han dynasty in 202 BCE. Many of the First Emperor’s reforms were retained. The small seal script, standardised weights and measures, and revised coinage continued to be used during the Han empire. Using the Qin bureaucratic system, the Han dynasty developed a highly centralised government and successfully ruled China for four centuries.

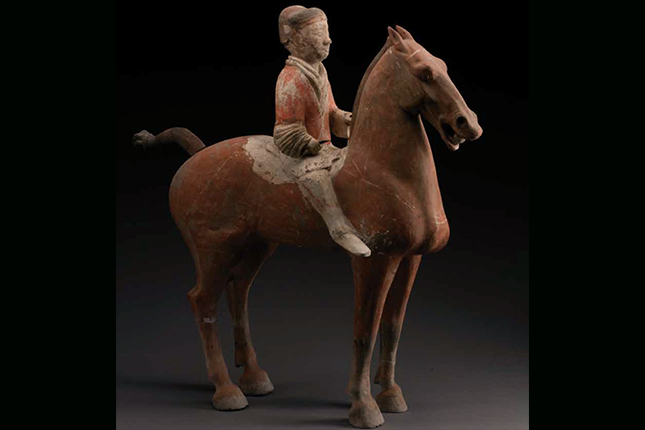

Han tombs, however, are very different from the First Emperor’s. It seems as though the first Han emperors, while retaining the long tradition of burying terracotta figures, wished to separate themselves as much as possible from Shi Huangdi. Early Han rulers preferred simplicity to sumptuousness, the miniature to monumentality. Compared to the life- size Qin terracotta figures, Han pottery figurines are much smaller and represent many aspects of daily life. In addition to soldiers and courtiers, Han tombs feature kitchens and domestic animals. The sacrificial pits around Emperor Jing’s mausoleum contain a great number of officials, entertainers and attendants. The faces of these figurines are softly contoured, usually with graceful facial expressions and serene smiles. The Han people’s affection for tranquillity and simplicity was based on the core concept of Daoism – the pursuit of harmony with nature.

In the pits around Yangling, the tomb of Emperor Jing, large numbers of soldiers were found naked and armless. Originally, they had wooden arms and wore costumes made of cotton and silk. Just as the First Emperor inherited a rich tradition, so was his legacy a powerful one. Although the Western Han dynasty tried its best to set itself apart from the notorious unifier of China, it followed the same ancient traditions of burial and preparation for the afterlife. The soldiers and court officials made in terracotta for Han tombs provide a fascinating contrast to the imposing Qin terracotta warriors. The First Emperor perhaps must now be regarded as a force in art as powerful as in military might and governmental authority. The terracotta warriors and the other objects from his tomb complex continue to startle and delight us because they are magnificent works of art.

Alan Chong was director of the Asian Civilisations Museum.