Text by Suhaimi Afandi, Mark Baildon and S N Chelva Rajah

Images by Suhaimi Afandi

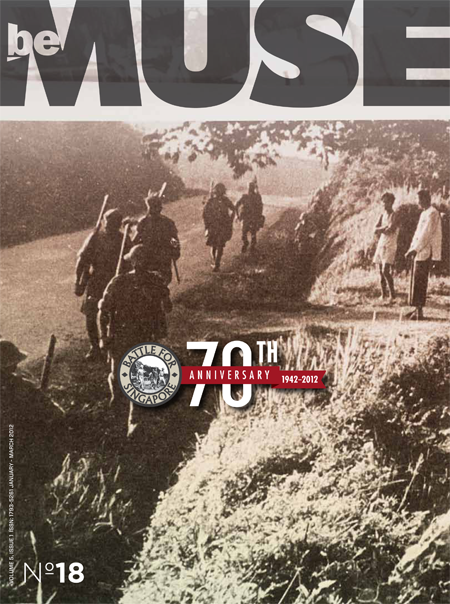

Be Muse Volume 7 Issue 4 - Oct to Dec 2014

Memorials or monuments that commemorate past wars are often intended to remind people of intensely-fought battles for national glory and triumph. At times, they serve as testimony to certain shared experiences fundamental to establishing a common destiny. Oftentimes, these sites - and what they represent - are also used to achieve larger political and social purposes, such as to instill patriotism and foster national identity, create collective memory, as well as imbue a sense of "continuity" of the historical legacies to be imparted to succeeding generations.

War memorials, monuments dedicated to past wars, and statues dedicated to military heroes are excellent historical sites that provide opportunities for young people to critically reflect the history they learn in classrooms, and evoke ideas and feelings they have about war, patriotism, and peace. Historical field trips to these sites can develop students' sense of empathy as they consider how different people were affected, and continue to be affected, by war and the ways war is represented in their cultures.

As history educators, we are frequently designing fieldwork activities to engage students in more critical and empathetic engagements with historical sites. Combined with an inquiry approach to fieldwork, we believe historical field trips can help students become careful and critical readers of artefacts, architecture, sites, monuments, historical markets, and museum displays as visual representations or sources of evidence about the past. The sites that students encounter on such trips can be critically analyzed, interpreted, and evaluated like other historical sources, instead of being passively received.

In this article, we offer guiding questions for historical field trips to help students "read" war memorials and monuments critically and with empathy. We define critical reading of historical sites as questioning how knowledge about the past is constructed and used. Tis means asking critical questions about why historical sites are created, techniques used to represent the past, and how they try to shape ideas people have about the past. Developing a disposition to empathise requires students to think about how different contexts, events, and issues shaped or affected people's lives and past actions. Empathetic readings require students to infer how people felt and thought in the past, based on evidence that memorials and monuments provide.

"Reading" Monuments and Memorials

Historical sites that represent particular interpretations or views of the past are often subject to intense debates both within and between societies. Helping students understand that historical sites can be read critically and with empathy is one way students can begin to interrogate different meanings associated with such sites, as well as their own and others' perspectives of these sites and the pasts they represent. Reading monuments for evidence, however, requires that students ask particular questions about the site(s) they are investigating.

We use the following guiding questions to help students critically read historical sites:

- What does this site tell me about the past?

- Describe the people, objects, symbols, actions, etc. that you see.

- What information about the past does the site provide?

- Who sponsored or created the site, and why was it created?

- What might they want viewers or visitors to think, believe or do? Explain.

- What techniques are used to influence me as a viewer?

- Why are certain objects or people shown or placed where they are?

- How are words, symbols or images used to influence what I think or feel?

An empathetic reading requires students to think carefully about the perspectives others might have about the sight and the past it represents. Some empathy-related questions include:

- What clues does the site provide about what people thought, felt, or did in the past?

- What evidence from the site supports my ideas?

- What contexts help me understand what people thought, felt, or did?

- What values or ideas are expressed through this site?

- In what ways does the site help me understand the perspectives people had about a particular part of the past?

- What evidence from the site supports my ideas?

- What are other ways different people might think or feel about this site and the history it represents?

- How might someone from a different country, culture, or perspective think and feel about this site and the history that it represents?

- Why might they have different reactions?

These questions can be tailored more specifically for students to directly engage with the war memorial or monument it was designed to commemorate.

Using Critical and Empathetic Questions with a War Memorial in Singapore

While any number of war memorials or monuments could be used for this activity, we selected the Kranji War Memorial to demonstrate how these critical and empathetic questions might be used with students. The answers to each question are written as first-person responses that might be typical of a student visiting the site.

What does the site tell me about the past?

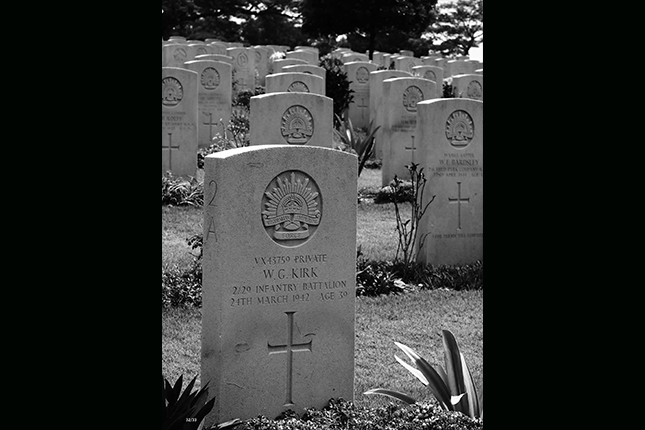

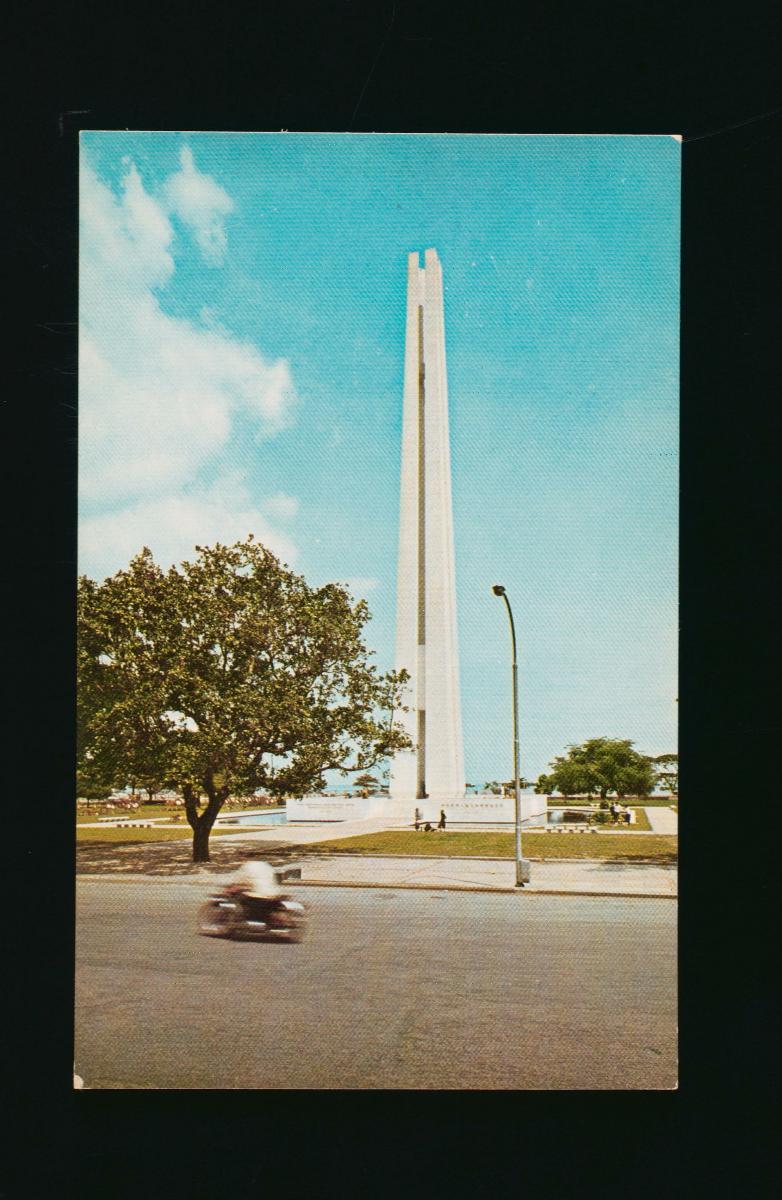

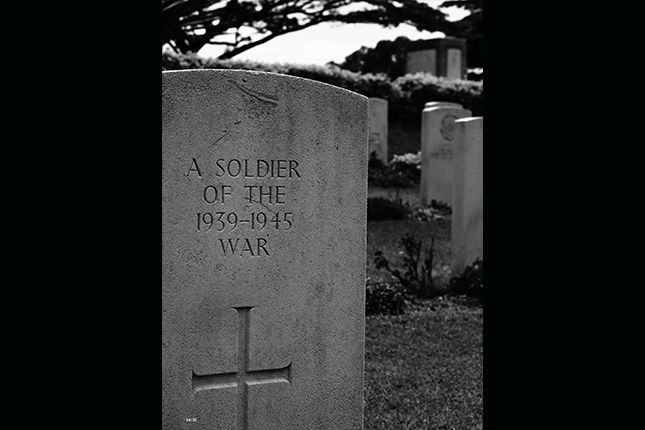

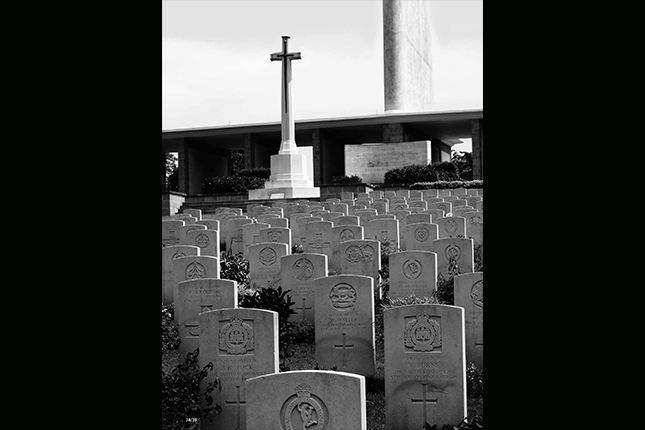

The Kranji War Memorial has several different areas and features. Each feature of the memorial includes different symbols and information about World War II and Singapore. A large Stone of Remembrance marks the entrance to the site and a gentle slope with gravestones leads up to the War Memorial at the top. The War Memorial columns represent the three branches of the military. The columns symbolize a marching Army; the cover over the columns represents the Air Force; there is a shape at the top of the memorial that resembles a Navy periscope. The memorial's walls making up each column include the names of over 24,000 allied servicemen who lost their lives in the war. There is a memorial cross at the site.

The memorial mainly provides the perspectives of the British Crown and Commonwealth nations that fought on behalf of Singapore and Malaya against the Japanese. It emphasises in bold letters that their deaths were for all free men. It tells me that the war and the great loss of life during the war were for freedom and to protect Singapore and Malaya from military aggression.

Who created the site and why was it created?

The site has great historical significance. Prior to the war, it was a British military camp and stored ammunition magazines. After Singapore fell, it was used by the Japanese as a prisoner-of-war camp. After the war ended, the site in 1946 was designated as Singapore's war cemetery, and military personnel who had been buried in other areas of Singapore were exhumed and buried at the Kranji site. This provided a central place of rest for the war dead and a focal point for remembrance of the war.

The memorial was designed by a Scottish architect, Colin St Clair Oakes, and was built to commemorate those who sacrificed their lives for Britain and its colony (Malaya) in World War II. These included military personnel from the UK, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, India, Malaya, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Singapore. The site is located in the north of Singapore where the Japanese invaded. The creators of the site probably wanted visitors to remember the lives that were lost and feel the loss in very real terms (by the tombs and names engraved on the memorial walls).

What techniques are used to influence me as a viewer?

The phrase "They died for all free men" and the engraving on the Stone of Remembrance that "Their name liveth for evermore" give the military deaths a much greater significance than solely defending Singapore and Malaya. Since the Japanese invaded and occupied Singapore, it connotes that although Singapore fell, the lives of the soldiers were not lost in vain.

The many rows of tombs as well as the names engraved on the memorial walls provide a powerful reminder of the many lives lost during the war. This makes me think of the sacrifice and great loss caused by the war.

The cross with a sword symbolizes military might. This is called a cross of sacrifice and it is apparently quite common in Commonwealth war cemeteries. The cross and swords pointing downward represent resting. While the cross of sacrifice suggests a religious focal point of the cemetery (as a symbol of Christianity), the Stone of Remembrance represents all faiths and shows the diversity of those commemorated by the memorial.

What clues does the site provide about what people thought, felt, or did in the past?

The creators of the site want people to know that the dead commemorated at the memorial gave their lives for freedom. A sign in Singapore's four official languages reminds viewers to preserve the peace and dignity of the site. It reminds viewers that people place great importance on the war and the loss of life and that it should always remain a significant place of respect for visitors.

The many plaques highlighting key battles during the war also display important information about the war that people should know. Not only is it a place that represents deep emotion for the fallen, solemn observation and reflection, it also is designed to inform. The plaques provide contextual information about the battle that helps viewers understand the historical contexts of the war and the war dead.

What values or ideas are expressed through the site?

The memorial reminds me of other war monuments or memorials that I've seen that similarly commemorate the war dead. It expresses the tragedy of the devastation and death caused by World War II, but also wants viewers to honour those who died. The inscription of "They died for all free men" makes me think that I should feel a certain indebtedness to those who died. It makes me think that maybe they died so that I might live in freedom. The idea or value of freedom, and that it has to be defended, seems central to the memorial.

By owing the names of every person who died, it marks the individual contributions made on behalf of the defence of Singapore and freedom. The people who constructed this site want future generations to remember the sacrifices made during the war so that Singaporeans and other visitors to the site may appreciate the importance of freedom and the need to defend it.

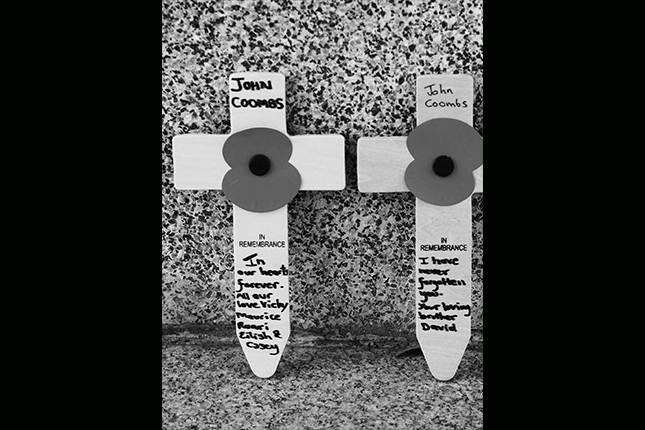

What are other ways different people might think or feel about this site and the history it represents?

Other people may have different interpretations and reactions to this site. If a member of your family had lost someone in the war, I think there would be a much more emotional reaction to the site. The site's plaque tell me more about the war - why it was fought, who else died, how it ended, etc. - so, it seems to want me to acknowledge the contribution made by the dead supposedly on the behalf of Singaporeans.

I think other people might have very different perspectives of the war, because people usually view war in very different ways depending on their values or backgrounds. Some might be angry at the loss of life caused by the war. Some might feel great sadness, and others might see this as a representation of the British Empire or colonial power, rather than having anything to do with Singapore. I know that many things are missing about the war and that the site wants me to focus only on honouring the dead.

The site also doesn't seem to acknowledge the lives of ordinary civilians who died during the war. There were many civilians in Singapore, for example, who resisted the Japanese and lost their lives. Their deaths are not commemorated at the site.

Conclusion

The questions we have proposed can be an integral part of historical fieldwork. They encourage students to consider the purpose of constructing war memorials and monuments, and also encourage students to think about and question their own and others' responses to these sites and to war. These questions can empower teachers and students to more fully understand how the past, present, and future are constructed through the interpretive practices that make up historical inquiry.

By giving students the opportunity to challenge accepted versions of the past (including their own) and develop their own or alternative interpretive accounts, they might better understand the role history education can play during peace-time.

Reading the past with empathy requires students to consider the perspectives and emotions of those affected by war, both in the past and the present. Through empathetic understanding, teachers and students can begin to consider how war impacts different people, the views on war and peace that others may hold, as well as their own responses to war and its consequences.

Suhaimi Afandi, Mark Baildon & S N Chelva Rajah are from the National Institute of Education