Text by Peter Lee and Naomi Wang

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 3 – Jan 2017

Port Cities: Multicultural Emporiums of Asia, 1500-1900 was on display at the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) from November 4, 2016 to February 19, 2017. Peranakan scholar Peter Lee, together with ACM’s former director Dr. Alan Chong, conceptualised this show, the first of its kind to explore the histories of Asian port cities through the perspective of local inhabitants, rather than European colonial ties and trading networks.

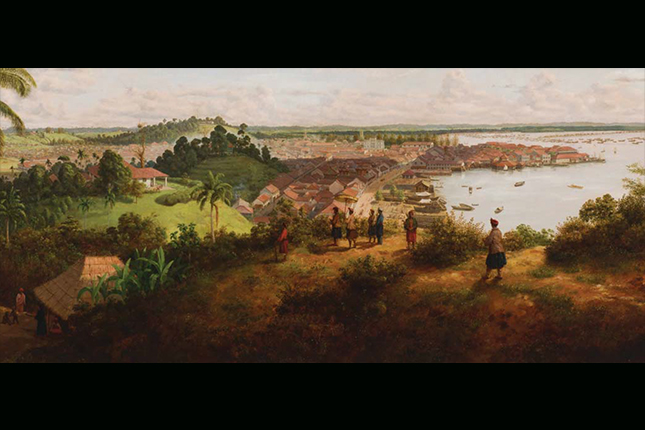

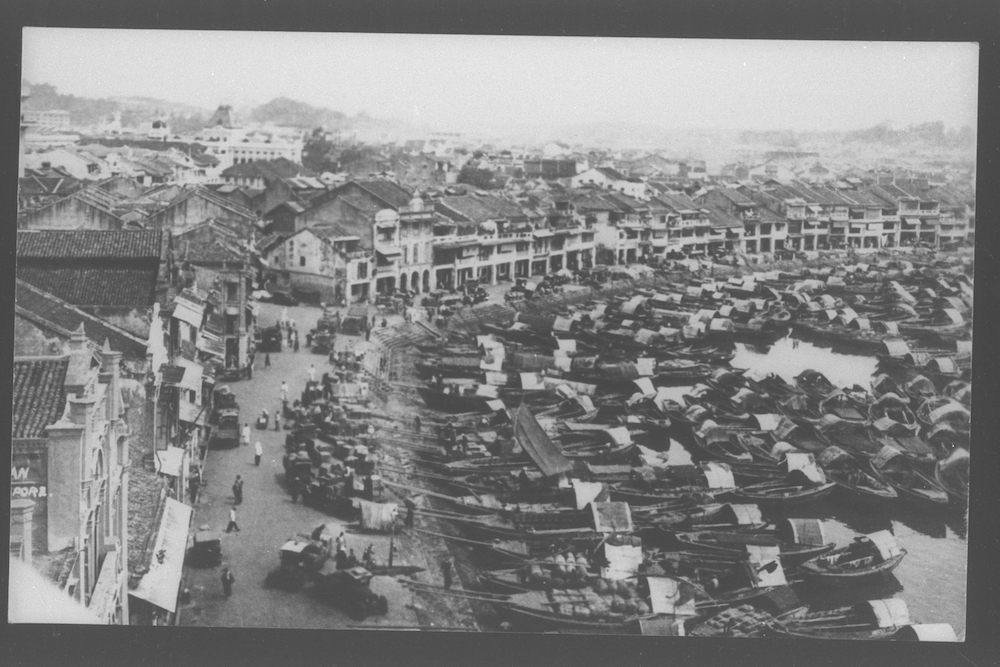

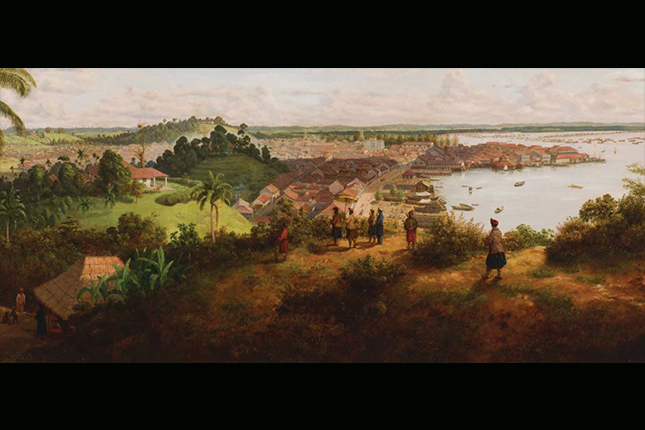

Port cities perfectly encapsulate a fundamental human process that has existed since time immemorial – the constant mixing of people, objects and ideas. These cities and the powerful cultural dynamics within and between them reflect how culture is formed, spread and shared. The story of port cities in Asia is the story of multiracial communities and networks. It is also the story of global trade, diverse consumption of objects and the spectrum of responses to them. Supply and demand engendered extensive competition, counterfeits, cheap replicas, as well as innovations and improvisations. New cultural forms emerged. Singapore – an active port in the mid-19th century, as depicted in the panoramic view painted by Percy Carpenter – is a large part of this story.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

Oceans and waterways facilitated the movement of people, ideas and goods, while climate and trade winds governed them. By considering three categories of cultural dynamics in Asia – divergence, convergence and integration – and by connecting contact points and the complexity and confusion of multi-directional cultural flows, the exhibition managed to elicit new ways of thinking about history.

In the period leading up to the 17th century, starting up life and trading in a new country took place against enormous odds. Those who succeeded reaped rich rewards and made a tremendous impact on material culture. The production of copies and cheap imitations, and their wide circulation created international styles and fashions. The rare example of a kimono made of Indian chintz is testament to the international circulation of textiles and their adaptation in local contexts. Over time, this creativity and the ever-changing dynamics of port cities facilitated what we understand today as modernity and globalisation, and also the development of popular culture.

New Places, New Lives

The exhibition began with an eclectic array of mannequins depicting 19th century inhabitants of Singapore. The presence of people from different backgrounds, dressed in their own fashions, was common not only in Singapore, but also in the many port cities of Asia. Five intimate stories of transnational communities which illustrate the diversity of port cities were told through the objects on display.

Mobile and enterprising, Chettiars have been trading beyond their homeland of the Chettinad region, in Tamil Nadu, India, for centuries. More than 200 years ago, Chettiars built temples in Saigon. Links were strengthened when Pondicherry (near Chettinad) and Saigon became part of the French colonial empire. The treasuries of Chettiar temples in Saigon were filled with ornate gold jewellery offered to deities as devotional embellishments. A gold prabhavali would have been placed around the image of a deity.

On long-term loan to Indian Heritage Centre, Singapore.

Cornelia van Nijenroode (estimated to have lived around 1629 to 1691) was born in Hirado, Japan, to a Dutch merchant and a geisha. This family portrait was made in Batavia, where she had gone after her father’s death. At the time, she was married to the wealthy Dutch merchant Pieter Cnoll. Upon Cnoll’s death, she became a very rich widow. Her marriage four years later to Johan Bitter and his subsequent attempts to take over her inheritance led to one of the most famous and acrimonious international court cases of the 17th century. It was fought all the way to The Hague, where she passed away.

Collection of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

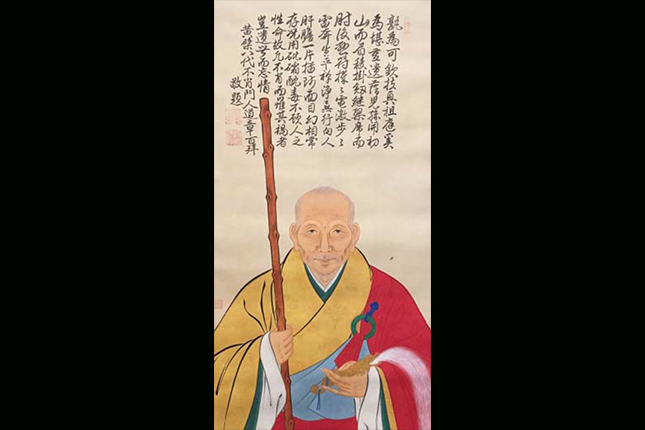

Dokutan Shoei is the Japanese name of the Chinese monk Duzhan Xingying (1628 to 1706), from Putian in Fujian province, China. Together with thirty other disciples, he followed his Zen master, Yinyuan Longqi (Ingen Ryu ̄ ki in Japanese), to the port city of Nagasaki, Japan, in 1654 to serve the Chinese population living there. Seven years later, Master Ingen established the O ̄ baku sect of Zen Buddhism, centred at Manpuku-ji in Uji, near Tokyo. Dokutan was part of this new sect and he later established a Zen temple, Shosan Horin-ji, in Hamamatsu. In addition to his Zen teachings, he also made paintings, three of which werepart of this exhibition. The practices of the O ̄ baku sect are closely linked with Pure Land Buddhism and Ming culture. Dokutan himself had a strong inclination towards Pure Land philosophy and also held strong Confucian attachments to his parents and ancestors.

Collection of Manpuku-ji Temple, Uji, Kyoto Prefecture.

Georg Franz Müller (1646 to 1723) grew up in the Alsace region of France and became a soldier of the United Dutch East Indian Company (Vereenigde OostIndische Compagnie, commonly abbreviated as VOC). He arrived in Java in 1670 to serve as a soldier in Batavia and other outposts. He studied the Malay language and kept an illustrated diary of his travels, making portraits of the various people in the region, as well as drawings of exotic flora and fauna. The diary also includes sketches of mermaids. When he returned to Europe, he worked for a Roman Catholic church in St Gallen, Switzerland. He left his diaries and other objects collected on his travels to that church before returning home in 1720.

Collection of Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen, Switzerland.

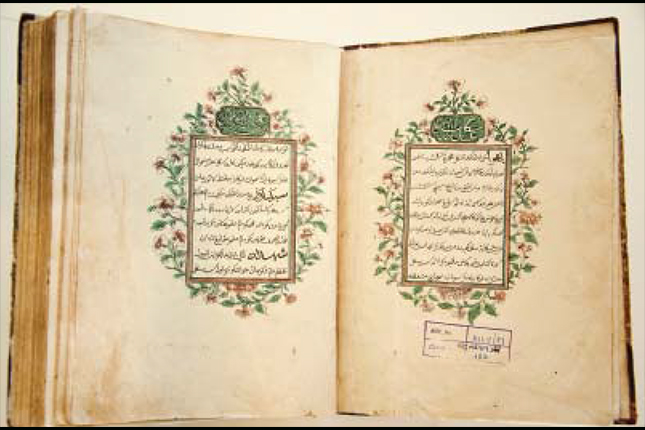

Hikayat Abdullah is the autobiography of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (1797 to 1854). Born in Malacca, he had a strict Muslim upbringing and scholarly education. The book is written in Jawi, and gives vivid accounts of everyday life and politics in Singapore, Malacca and the region. For his literary contributions, Abdullah is often referred to as the “father of modern Malay literature".

Collection of National Library Board.

Owning, Collecting, and Commissioning

The convergence of people and goods in port cities was made visible by diverse architecture and imported international goods. The multicultural populations spurred conspicuous consumption, social competition and an increasingly globalised marketplace. Unified tastes and fashions became the norm. Members of various communities residing in a port city often coveted the same luxury objects and imported goods. The material culture of port cities was therefore dominated by the coexistence of a comprehensive array of imported goods from the whole of Asia.

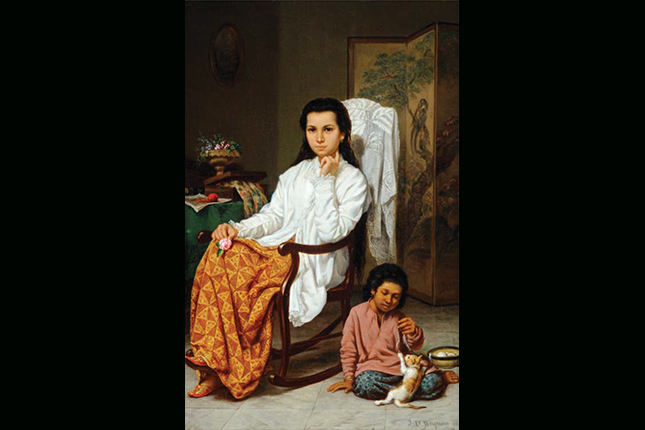

One section of the exhibition was devoted to objects from Batavia, perhaps the most important port city in Asia in the 18th century. International goods circulated widely among its multiracial residents, who sported the latest fashions. The flood of Asian goods into this metropolis was probably unprecedented in history. Jan Daniël Beijnon’s painting of a Eurasian woman from Batavia shows an interior space filled with imported goods from Asia. The silk tablecloth and Chinese wooden folding screen (also referred to as a Coromandel screen, after the name of the Indian port from which these screens were exported) were common luxury goods of Asia.

Collection of Mr Jan Veenendaal.

Mayhem: The Dark Side of Dynamic Encounters

Underlying the extraordinary convergences of people was the brutality of travel and urban life. Piracy was rife, mortality on voyages high and among warring nationalities, the plunder of cargo was justified as legal booty. Commerce was often conducted under mercenary and violent terms, and involved harming competitors, forcing agreements, then ignoring agreed-upon terms of such agreements. Trade and armed force went together hand in hand.

Slavery and human trafficking had great impact on urban society, intensifying the racial diversity of the population. Political and religious leaders put into place extremely ruthless measures to control the population. Japan, for example, underwent a period of isolationism under the sakoku (literally “closed country”) policy from 1633 to 1866. Strict restrictions were put in place on the entry of foreigners and the movement of Japanese people abroad. An official 1808 document from the Hirado archives details foreigners who were detained by Japanese authorities due to their illegal entry into Japan. Regulations on the population, however, did not stop violent upheavals nor the whole range of human vices, including murder, gambling, prostitution and illicit drugs.

Collection of Matsura Historical Museum, Hirado.

Contriving, Combining, and Creating

The concentration of diversity in port cities engendered not only racially hybrid communities, but also a multiplicity of hybrid forms. Adaptations and improvisations were the norm because of the commercial nature of most aspects of cultural output. In environments where migrants far from their motherlands made up a large percentage of the population, the traditional was often transgressed. These modern elements can be traced through the material culture of port cities, in the heterogeneous forms and trends, and in the diversity of objects. A locally produced chair from 18th century Batavia features hybrid forms that are a mix of Dutch and Chinese designs. In addition, Chinese-style lacquer coating indicates that the chair was the work of Chinese craftsmen in Batavia.

Collection of Gereja Sion (Portuguese Zion Church), Jakarta.

Increasingly, itinerant craftsmen of different nationalities offered their services in every port of call and were adept at producing work in a range of styles. Consequently, many categories of objects do not have clear provenance. The complexity, chaos and creativity of port cities reveals that globalisation and multicultural, hybrid environments are not new at all. Rather, they are a persistent and ancient phenomena.

Ultimately, they also raise deep questions about whether anything can or needs to be considered homogenous or pure.

The material culture of mixed-race communities illustrates this hybrid quality through the adaptation of new fashions and styles. Adaptation and use of the sarong kebaya by Peranakan nyonyas, for instance, reveals hybrid influences stretching from Europe and southern Africa through to the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum. Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

Sarong. Signed: Lien Metzelaar. Java, late 19th or 20th century Cotton (drawn batik).

Collection of the Peranakan Museum.

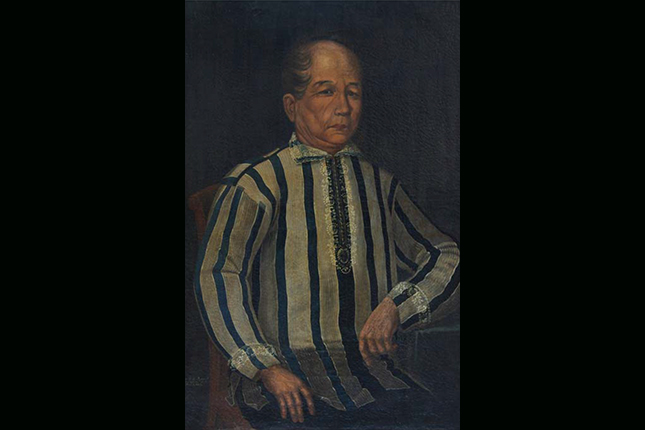

The person in the Portrait of a Man in Barong Tagalog has been identified as Don Paterno Molo y San Agustin, called Paterno Molo (1786 to 1853). This painting represents the earliest known dated portrait of a local painted by a Filipino artist. Paterno Molo belonged to an important Chinese- Filipino merchant family who were suppliers of Chinese goods destined for re-export in the Galleon Trade to New Spain. The family’s descendants are still prominent in Filipino society today. Portraits like this are indicative of the emergence of a native middle class, who conscious of their newly attained achievement and status, drove the demand for privately commissioned portraits during the mid-19th century. The barong tagalog is today considered one of the forms of national dress in the Philippines. In this picture, the high collar was inspired by Spanish outfits of the period.

Collection of Mr Jamie C. Laya.