Back in the days when a journey to far off lands usually meant a long sea voyage, ports were the hubs of exchange – a merchant’s gateway to international trade, a captain’s safe harbour to refuel and a land of opportunity for anyone willing to work hard.

When it was called Temasek, Singapore was one of many port cities situated along the Straits of Malacca; the gateway in and out of Southeast Asia. It had a deep sea harbour and was strategically located between India and China, making it a promising entrepot.

Singapore’s growth as a port

Leveraging the island’s reputation as an ancient port of importance with traders in the region, the groundwork laid by Major-General William Farquhar and aspirations of Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819 caused Singapore to become one of the premier places for international trade, business and success.

In contrast to the Dutch – another maritime power that controlled trade in the Malay Archipelago – the decision by Raffles to make Singapore a free port attracted merchants from the region and beyond. In just two years, almost 3,000 vessels with 200,000 tonnes of cargo visited the port, and in four years, the population had grown to more than 10,000.

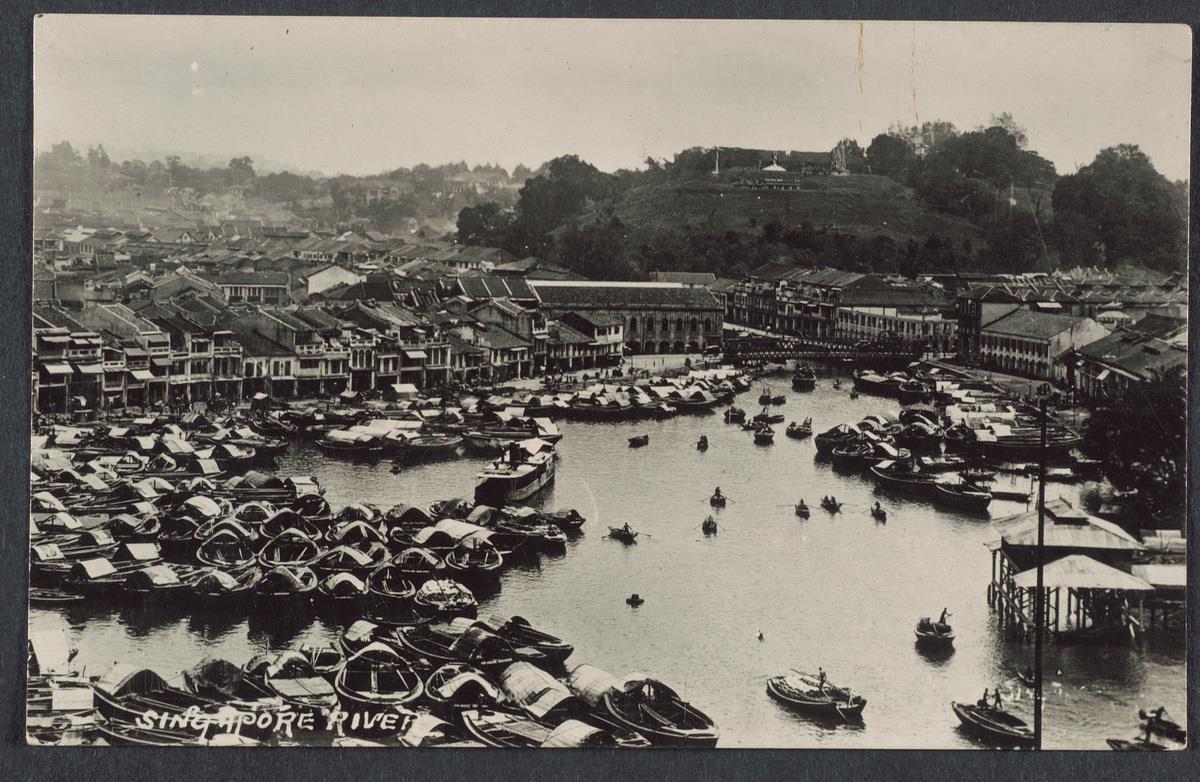

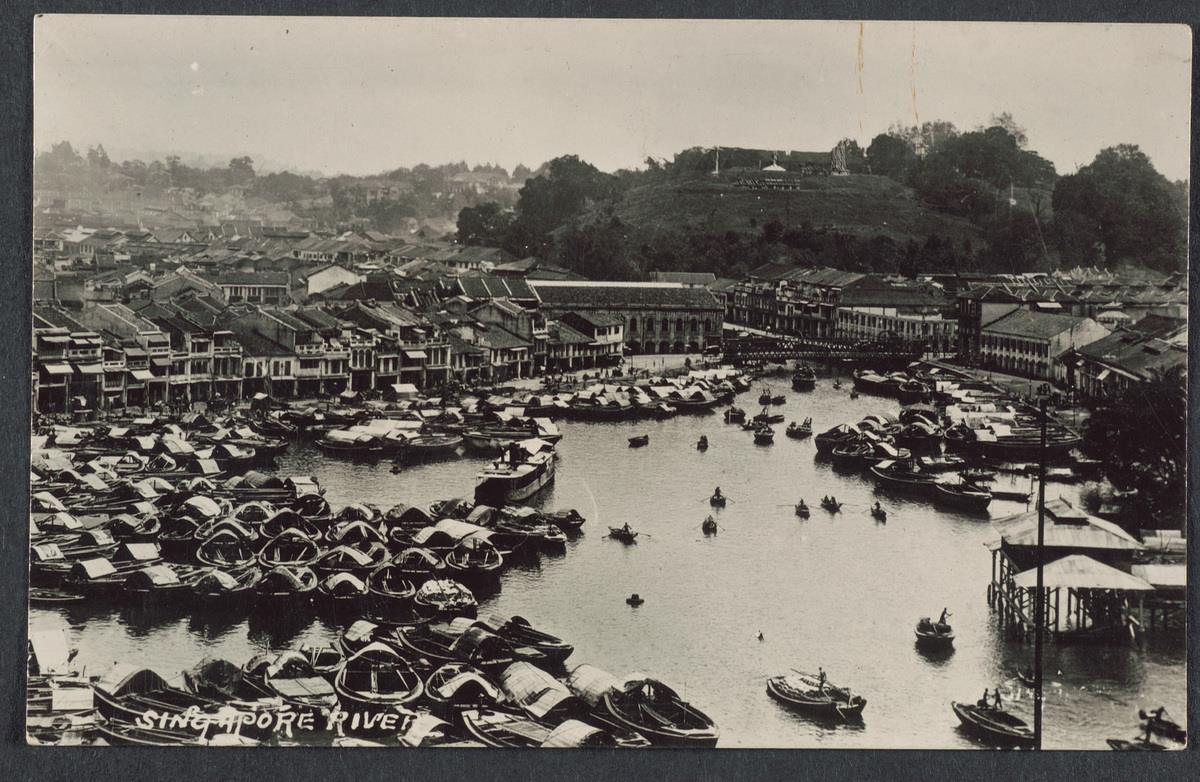

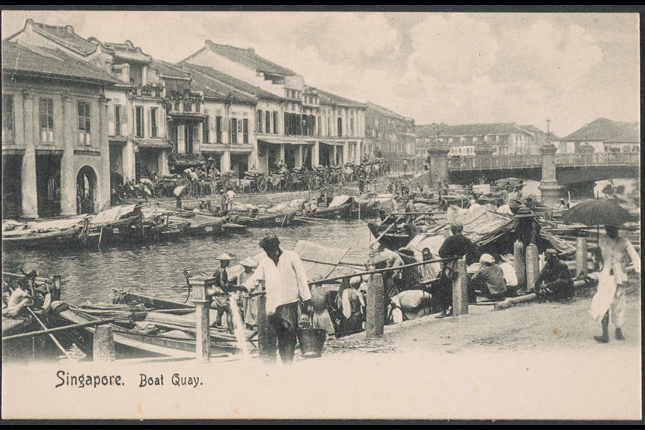

Along the winding river, Boat Quay would be the first stretch to experience the transformation. This particular part of the river became known as the “Belly of the Carp” because of its curved shape which resembled the fish, deemed an auspicious symbol by the Chinese. It was at this location that many godowns and warehouses were built. It quickly became crowded with cargo-packed bumboats. The sight of junks and cargo boats with flapping sails became a common sight on the river.

Singapore soon became one of the most popular ports to trade at. Besides serving as the centre of trade in Southeast Asia, the island overtook Batavia as the main hub for Chinese junk trade. This was only the beginning, and Singapore eventually supplanted the Riau Islands as the export gateway for the gambier and pepper industry of the Riau-Lingga Archipelago, as well as South Johor. Even the Teochew trade in marine produce and rice came to our shores.

Constructing roads and architecture

A significant milestone in the evolution of the port was the construction of roads and railways to support the bustling sea trade. Primary materials such as crude oil, rubber and tin from the Malay Peninsula were transported to Singapore for further processing into staple products, before being shipped off to Britain and other international markets.

Besides the merchants and businessmen, the types of visitors started to grow to include a mix of travellers and seamen. “La Favourite”, a French corvette on a voyage to sail around the world, also found respite in Singapore’s safe harbour for five days en route to far-off New Zealand.

Raffles directed land on the north bank to be reserved for government buildings; the east of this plot was allocated to the Europeans, and further east for the Arabs and Bugis. However, the needs of commerce thwarted this plan to some extent, as both European and Asian merchants preferred to locate their businesses by the riverside. Flat and spacious river banks were soon lined with trade houses. These diversified the landscape and were soon followed by the brick warehouses, also known as godowns, ready to receive and store goods arriving on Singapore’s shores.

Ocean-faring vessels were too large to navigate the shallow waters of Singapore River. Instead, smaller flat-bottomed craft called lighters or bumboats would ferry cargo between these ships and the docks at the river.

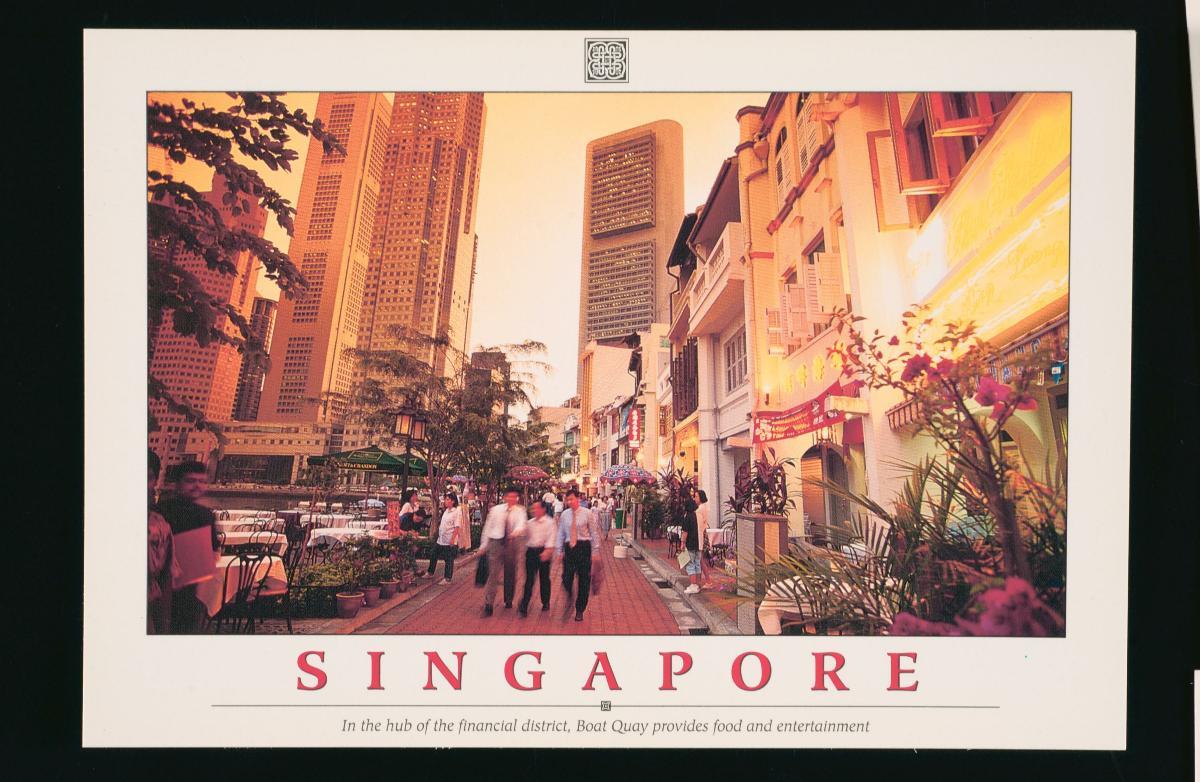

Commercial hubs such as Raffles Place, Market Street and Fullerton Square also emerged in the river’s vicinity as merchants and bankers gathered to exchange news and seize business opportunities, forming one of the key economic pillars of independent Singapore.

The Singapore River Settlement was captured by artist Percy Carpenter in the “View of Singapore from Mount Wallich” (which has now since been levelled for the land reclamation of Telok Ayer) in the 1850s. One can identify other landmarks in the painting such as the Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Cathedral of the Good Shepherd and St Andrew’s Church.

But architecture and buildings were not the only things brightening up river life. The river was also filled with people of diverse communities who came from various parts of the world; some for work, and some for rest and recreation.

People along the River

Armies of coolies, lightermen and stevedores (dockworkers) toiled to unload bales of merchandise into riverside shops and warehouses, while new arrivals came ashore to seek their kinsmen and business associates, or look for work. After a long, hard day work, many who worked by the river would unwind on bridges such as Read Bridge and Coleman Bridge to enjoy a drink and listen to traditional storytellers.

These storytellers would entertain the river communities with tall tales and live music. At a time when literacy was low, newspaper readers would also draw crowds, serving an important function by keeping everyone abreast of the latest happenings.

This mingling of people from all corners of the globe led to cultures and traditions intersecting and interacting on a daily basis on our shores. The port built upon the banks of the Singapore River facilitated not just an exchange of goods, but also of cultures and dreams of building a future.

The Singapore River no longer functions as a harbour for trade, but it continues to flow past important landmarks, buildings and neighbourhoods that serve as a reminder of how modern Singapore began; with the establishment of a trading settlement and through the diverse communities who built and shaped it into the international hub it is today.