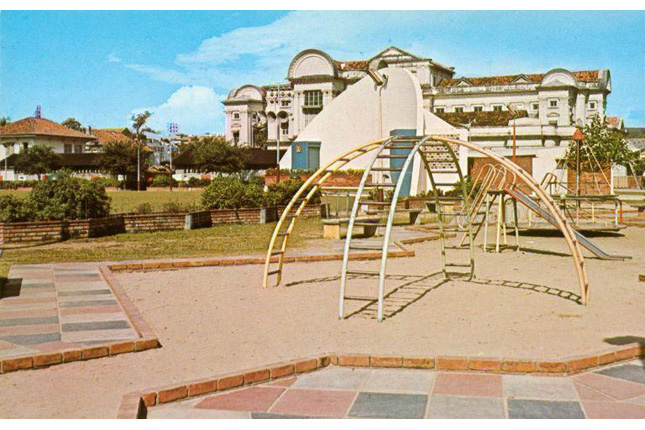

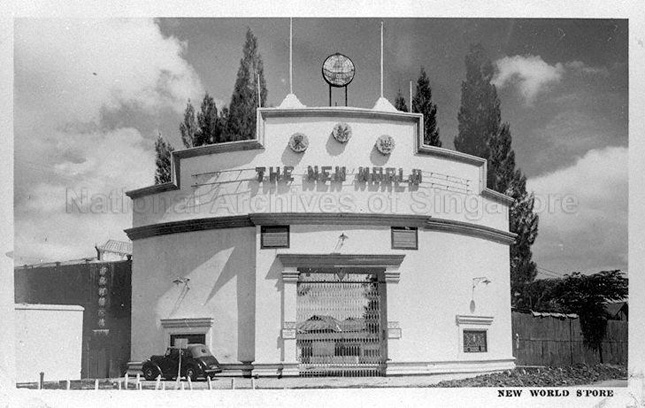

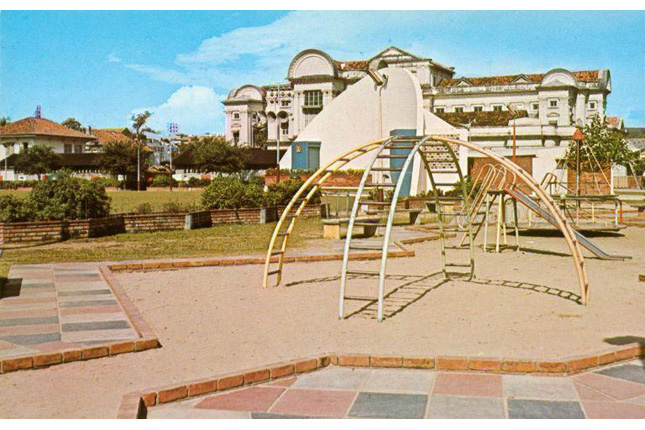

A playground at Hong Lim Park Green in the 1960s. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

A playground at Hong Lim Park Green in the 1960s. (Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

All work and no play makes…

Given the mercantile priorities of the colony, designing the city for children was low on the list for the British. So how and where did children play? In the congested city centre, they carved out their own nooks and play spaces in open drains and five-foot ways.2 In the outer belt,3 they ventured outdoors spinning tops, throwing marbles, fighting fish and flying kites.4

Over time, the colony’s demographics evolved and its denizens made it clear that there was a need to better serve Singapore’s younger populace. This desire was partly influenced by the international playground movement that started in 19th century America5 which posited that dedicated playsites could serve as gathering points for neighbours and build cohesive communities in crowded cities.6

Members of the Singapore public began writing to the press suggesting playgrounds be built and open fields set aside for general well-being. Businesses and businessmen such as Huat Hin Oil Company, the Singapore Traction Company, the Siong Lim Sawmill Company, Aw Boon Haw and David J. Elias responded by financing the first few playgrounds in Singapore. Import and export merchant Elias, for instance, donated swings, a see-saw and a slide to Katong Park.

The colonial government officially swung into action in 1951. It set up a Playing Fields Committee which found that just 250 acres or so of space had been set aside for the sports and recreation needs of its 700,000 occupants. It thus recommended the addition of more recreational spaces. In 1953, the British-run Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) added play equipment to Queenstown, Singapore’s first satellite town. The playgrounds of 1950s and 1960s Singapore were basic and functional in nature, comprising simple slides, swings and see-saws.

Dragons, doves and pelicans — the iconic playgrounds of Singapore

When the Housing Development Board (HDB) took over from the SIT in 1960, it decided to design playgrounds that drew on local heritage and culture to help create stronger communal bonds.

The board’s playgrounds typically comprised simple, geometric or animal-shaped concrete structures in sand pits.8 Its first playground designer, trained architect Khor Ean Ghee, was largely responsible for this. He designed more than 30 playground prototypes which HDB architects could take their pick from. Many of these models also featured terrazzo tile work as well as swings fashioned out of tyre and rope.

The dragon playground is the most famous of these early HDB playgrounds. Children can totter up the dragon’s tail, walk along its long body and slide down its head.

Built in 1979, the dragon playground at 28 Lorong 6 Toa Payoh is a well-loved landmark. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Built in 1979, the dragon playground at 28 Lorong 6 Toa Payoh is a well-loved landmark. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

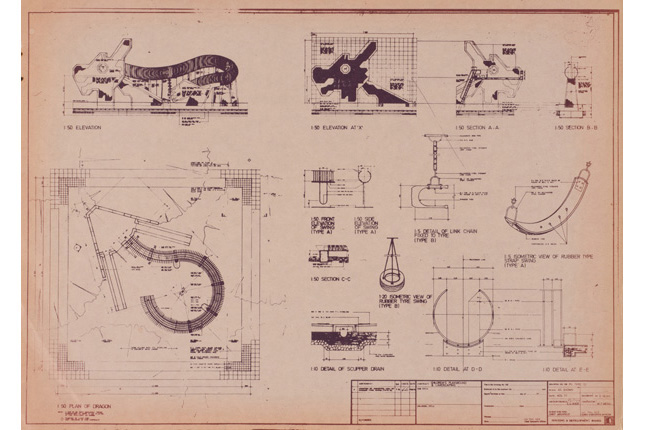

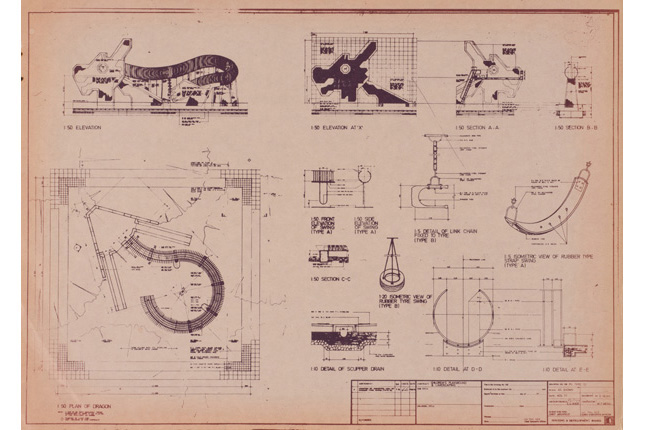

A prototype drawing of the dragon playground. The dragon was chosen as a symbol to help establish a stronger Asian identity. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A prototype drawing of the dragon playground. The dragon was chosen as a symbol to help establish a stronger Asian identity. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

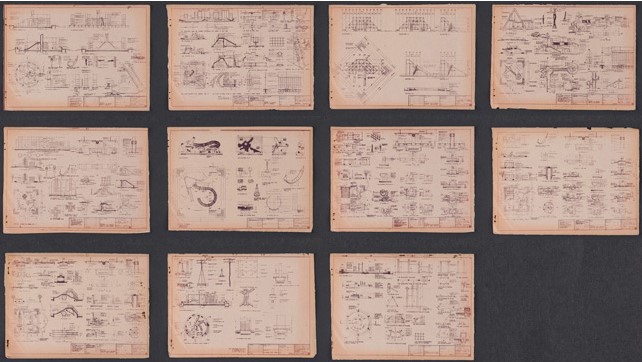

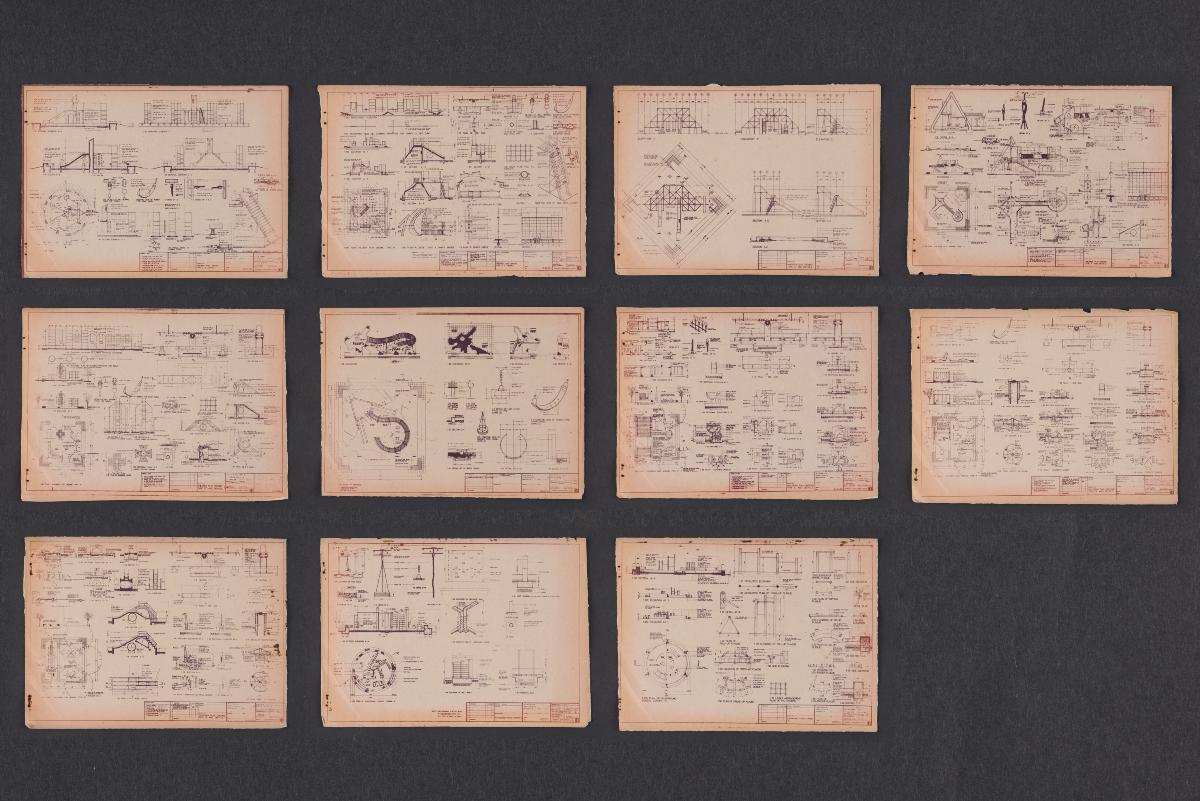

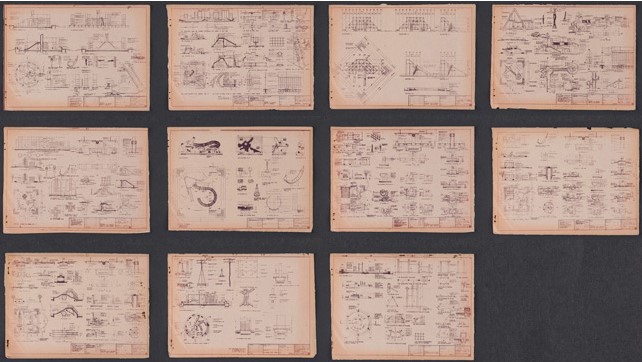

Khor Ean Ghee's personal copies of the prototype playground designs. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

Khor Ean Ghee's personal copies of the prototype playground designs. (c1970–1979. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

A pelican playground at Bedok Reservoir Road. (c1984. Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

A pelican playground at Bedok Reservoir Road. (c1984. Image from the National Archives of Singapore)

Dakota Crescent's dove playground. (c2014. Image from ghettosingapore.com)

Dakota Crescent's dove playground. (c2014. Image from ghettosingapore.com)

Themed playgrounds of the 1980s

The next wave of playgrounds was designed by Chew Chek Peng. Her designs took on storytelling elements grounded in themes of identity and culture.

Take Tampines’ fruit-based playgrounds. There, larger-than-life watermelon slices and mangosteens take centre stage, paying homage to the estate’s fruit farm days.9 The colourful additions command attention, drawing children into a world where fruits are king.

No longer child’s play

The 1990s gave rise to a new playground building industry as private companies rose to take on the responsibility previously held by the HDB. They had to meet national safety standards rolled out in 1999 by Spring Singapore, which spelled out specifications such as allowable materials. Playgrounds thus began looking modular.

These days, playgrounds are incorporated with fitness corners to encourage multigenerational bonding. On average, one playground serves about 600 to 800 flats.10

There are about 10 playground builders today. Apart from HDB playgrounds, they also develop play areas for malls, entertainment venues and parks, some of which cost several million dollars to build.11 Singapore has indeed come a long way from the $2,000 playgrounds of the 1920s.