Text by Ian Tan Yuk Hong

Be Muse Volume 8 Issue 1 – Apr to June 2015

In recent years, the display of human remains has become a topic of discussion in Western countries, particularly those with a history of colonialism. The Codes of Ethics provided by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and the Museum Association UK offer guidelines on how to handle such collections and address questions of aims, but they are primarily intended for Western societies that deal with opposition from “people of origin” – the descendants of the people whose remains are displayed. The guidelines do not specifically address human remains at museums in regions from which they originated.

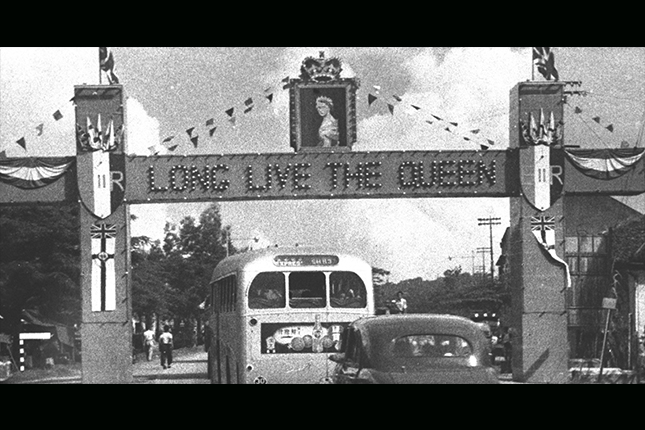

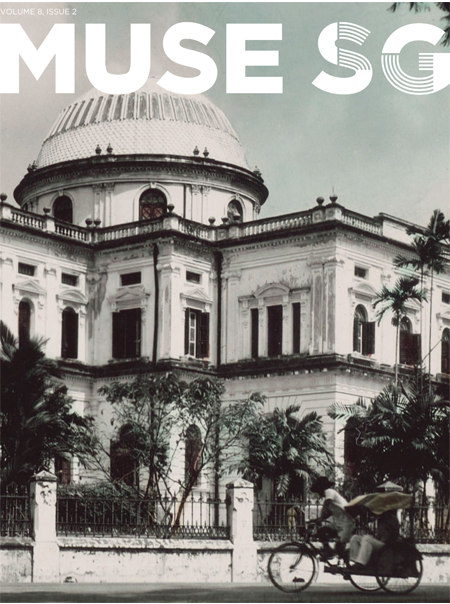

As a former British colony in Southeast Asia, Singapore assimilates its familiarity with Asian cultures with concepts of museum governance based on western principles. Hence, it is in a good position to reconsider how such artefacts may be treated with sensitivity.

A Modern Framework For Handling Ancient Human Remains

Human remains in museums have historically been “implicated in situations of inequality”. In the United States, laws for the repatriation of human remains, such as the Native American Graves Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990, accorded indigenous communities “equal rights regarding their dead”. This paved the way for overseas communities to request for their ancestors’ remains from museums worldwide.

In the United Kingdom, laws allowing museum collections to be held for perpetuity were relaxed after unrelenting campaigning from such groups. Since 1995, the British Museum has received six requests from organisations - including the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre and the Museum of New Zealand - making claims on its collections of human remains.

The British Department for Culture, Media and Sports eventually produced guidelines for the care and return of human remains in 2005. Similar provisions were also drafted for the Museum Association UK and the American Alliance of Museums, iterating the need for a formal framework to manage human remains on display in a sensitive and culturally appropriate manner.

The late ICOM Code of Professional Ethics, revised and adopted in 2004, stated that the display of human remains must “take into account the interests and beliefs of members of the community, ethnic or religious groups from whom the objects originated.” The code also highlighted the possibility of “originating communities” requesting for the removal and return of such remains from public display, and how museums could address these requests “expeditiously with respect and sensitivity”. As the secretariat of ICOM Singapore, the National Heritage Board (NHB) and its member museums in Singapore must adhere to the ICOM Code of Professional Ethics.

In particular, the way human remains are handled in three of the NHB’s member museums in Singapore is note-worthy. The collections in the Asian Civilisation Museum (ACM), the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, and the Department of Anatomy Museum in the National University of Singapore (NUS) are ethnographical, religious and medical in nature respectively. This allows us to see how different curatorial directions affect the treatment of human remains, and if such approaches may signal a way for other museums worldwide to follow.

A Level-headed Approach to a Headhunting Tradition

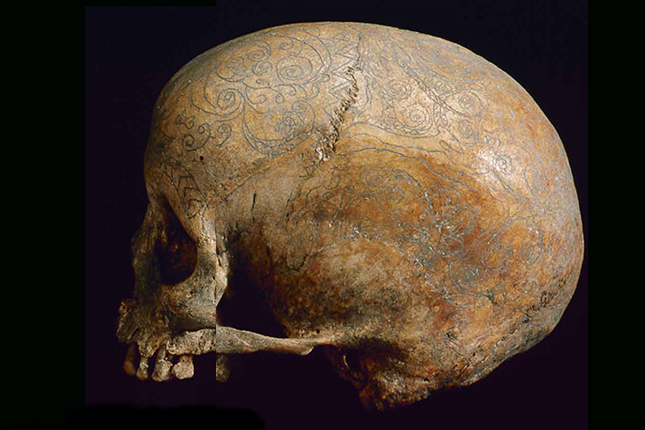

The ACM is an ethnographic museum that focuses on pan-Asian cultures and civilisations, including those originating from China, Southeast Asia, South Asia and West Asia. The Dayak Carved Human Skull is the centrepiece of a permanent display showcasing the lifestyle of the indigenous Dayak tribe of Borneo. It is physical proof that the Dayaks engaged in headhunting activities, even though the practice has long been outlawed by Malaysian and Indonesian governments in Borneo.

ACM went to great lengths to assure visitors that headhunting was not a form of brutal tribal behaviour. The catalogue gave a balanced view by explaining how the Dayak tradition of headhunting was an honourable means to “improve the community’s well-being” as human heads were “believed to contain a powerful beneficial spiritual essence”. In fact human heads were treated respectfully by the Dayaks. Major rituals followed each successful headhunting expedition. Captured heads were honoured and proudly displayed in the ancestral longhouse. Elaborate swirl patterns on the skulls show that these were not merely war trophies, but revered artefacts.

ACM thus framed its curation of the Dayak human skull within an anthropological understanding of the Dayak tribe. The Dayaks are portrayed as an important component of Nusantara (Malay world). The museum also noted similarities in social structures found in some communities in Riau-Lingga sultanates, where Singapore’s Malay community draws its ancestry.

Other museums such as Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and the Pennsylvanian Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum), which also included Dayak carved skulls in its collections, treated these artefacts with similar sensitivity. In a special volume of Penn Museum’s Expedition magazine, the tribe’s practice of headhunting was described in the social context of “contributing to the prosperity of community through performance of certain important rituals, such as the Iban Dayak kenyalang, which required fresh human heads for their performance”.

Curating The Religious Remains Of Buddha

The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum serves two functions. Firstly, it honours the tooth relic and other Buddhist relics, or sarira, purportedly from Gautama Buddha. Secondly, the temple exhibits these relics and other religious artefacts in a museum setting to impart Dharma and promote awareness of the faith.

The relics from Buddha’s remains are venerated and enshrined in elaborate reliquaries housed in the museum’s Relics Chamber. In Buddhism, the crystal-like sarira is the embodiment of spiritual energy culminated by Buddha and eminent monks during their lifetimes, and represent a person’s “sangha” or Buddhism learning. Buddhists believe that before Buddha’s departure, he had said: “...if thou all see my relics, it would be as good as meeting in person, as good as learning the Dharma and as good as knowing nirvana.” Hence, relics associated with Buddha’s remains are highly regarded by the religion’s devotees.

The centrepiece of the museum, the Buddha Tooth relic, is housed in a 3.6m-high stupa made with 270kg of gold that was donated by devotees. Buddhists believe that “relics can grow and multiply”, which may be seen as not only a testament of faith, but also a departure from conventional Asian attitudes in that devotees do not view exhibiting these remains as culturally taboo. Similar beliefs are seen elsewhere: Sri Lankan Buddhists view relics enshrined in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy as a means of receiving Buddha’s blessings and to “procure wishes for economic wealth and health.” The translocation of the Buddha Tooth from Sri Lanka to the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in Singapore is also an example of how Buddhism may be spread via the veneration of these relics.

The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum and its curation of Buddha’s remains are driven by the veneration for the Buddha Tooth and sarira. Its curatorial approach also focuses on how the display of such relics represent the religion’s beliefs and their spread across Asia.

Respecting a School’s “Silent Mentors”

At the Anatomy Museum (AM) in NUS, embalmed cadavers hold specific parts of the human body, which are arranged anatomically. The curatorial approach of AM may be described as that of a teaching museum founded on the educational needs of medical students and instructors.

The cadavers on display came from donors who had pledged their bodies for medical use after their deaths. That said, the bodies are only dissected and embalmed after a “claims” period of three years. As some facial features are still discernible, AM does not allow its handlers or viewers to take any pictures as a mark of respect. Students are also prohibited from making “Humourous and derogatory remarks” towards the cadavers. Visits to the museum must be booked ahead, and access is usually granted only to medical students and practitioners. Similar guidelines are practised in other pathology museums, including the Wellcome Museum in the Royal College of Surgeons, and The Gordon Museum in King’s College in the UK.

Unlike the controversial Body Worlds exhibition that showed plastinated cadavers in positions mimicking horse riding, fencing and swimming, the cadavers on display in AM are treated respectfully. Cadavers come with detailed write-ups of the donors’ medical histories which highlight the museum’s emphasis on education. The museum also runs a “Silent Mentor” programme that provides information for body donation, and holds an annual ceremony to show its appreciation towards “once living individuals whose bodies are used to impart invaluable anatomical knowledge”. These practices demonstrate a unique way for treating human remains with dignity.

Paving The Way Forward

Academics argue that exhibiting human remains perpetuates a “construction of otherness within an anthropological discourse that tends to privilege the visual and the spatial”. In other words, the once-living person is now viewed with a sense of detachment in the museum – not unlike an exotic artefact. Curation practices in these three Singapore museums thus demonstrate the importance of placing human remains within a larger context. From portraying headhunting as a unique ritual practised by Dayaks, to the veneration of Buddha’s relics as religious devotion, and the role of silent mentors, donated cadavers, play to students of the human body, all three museums have own a way to fulfill their respective curatorial objectives, while still according the remains with the deepest respect possible.

Ian Tan Yuk Hong is an Assistant Manager/Heritage Planning, Impact Assessment & Mitigation with the National Heritage Board