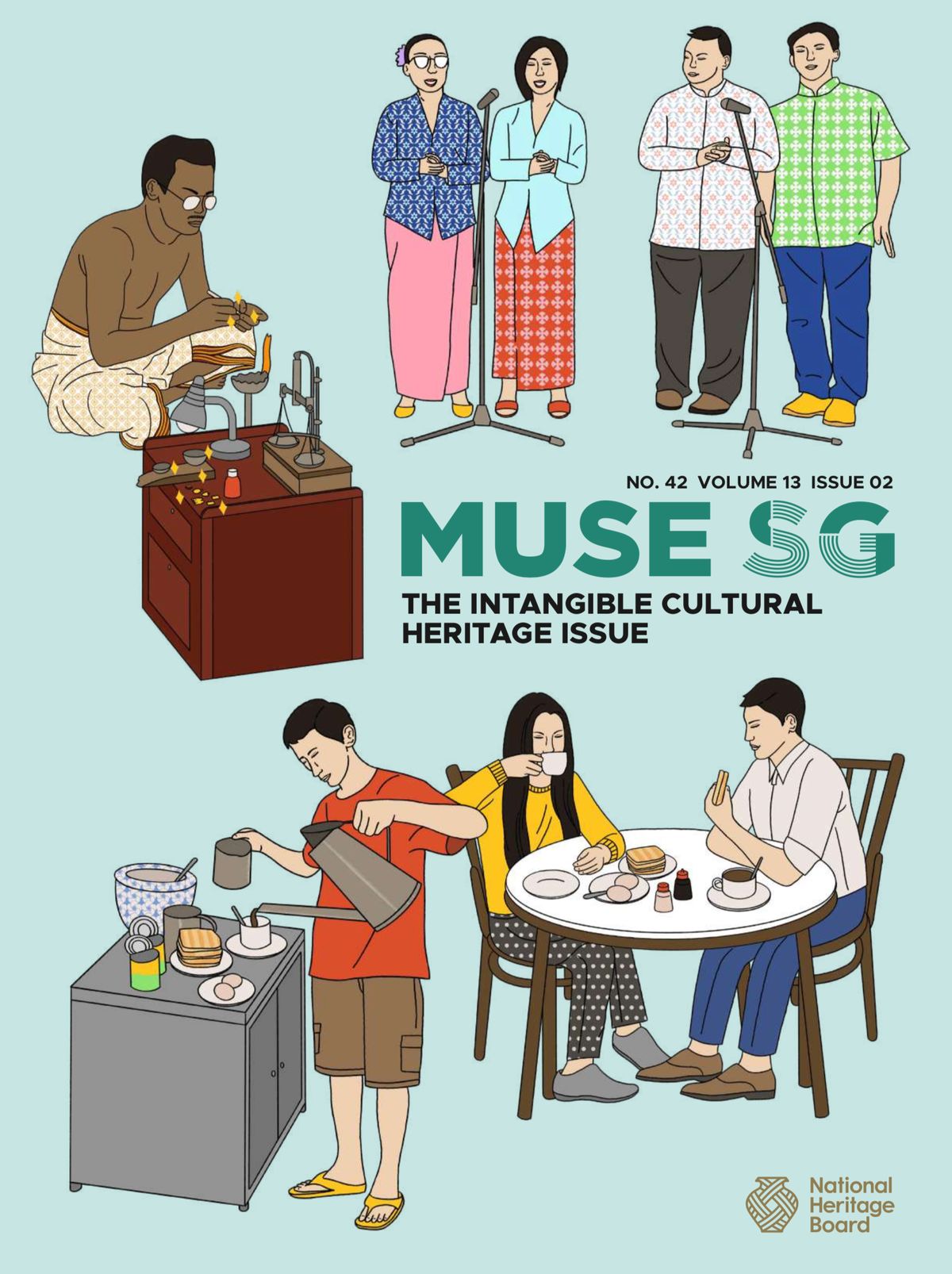

Making of Gold Jewellery by Indian Goldsmiths

In Indian culture, gold jewellery is traditionally worn by both men and women during festive and religious occasions. It is also given as gifts to close family members, especially during weddings. The goldsmith crafts jewellery completely by hand, in contrast to machine-made jewellery sold in other stores. Using a small burner and tools such as files and hammers, he shapes and carves the gold to the design he and his customer has in mind.

Besides making jewellery, the goldsmith also offers services such as repair, alteration, cleaning and polishing, trade-in of old jewellery for new jewellery, and gold plating. Some goldsmiths offer ear and nose piercing services as well.

Most Indian goldsmiths in Singapore arrived in the late 1940s from southern India, especially from Tamil Nadu. The trade became popular in the 1950s, with about 500 goldsmiths during its heyday.

Geographic Location

The practice by Indian goldsmiths is present in places with Indian diaspora. In Singapore, the goldsmith shops specialising in handcrafted jewellery and repair works are located in Little India.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, there used to be a large number of Indian goldsmiths who had practiced their trade in the area of Buffalo Road during the 1950s. Customers included both Indian and Chinese families who would request customised jewellery for special occasions such as weddings and festive celebrations. Popular jewellery items would include necklaces, bracelets, rings and hair ornaments.

Most Indian goldsmiths in Singapore come from the vishwakarma caste, which comprises five professions – goldsmiths, carpenters, blacksmiths, bronze smiths, and stonemasons.

Many of the jewellery and goldsmith stores in Little India are part of the Little India Shopkeepers & Heritage Association (LISHA).

The Indian community as well as the wider community in Singapore is involved in the supporting the practice, when they wear or give these handcrafted gold jewellery as gifts to friends and relatives during festive occasions.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

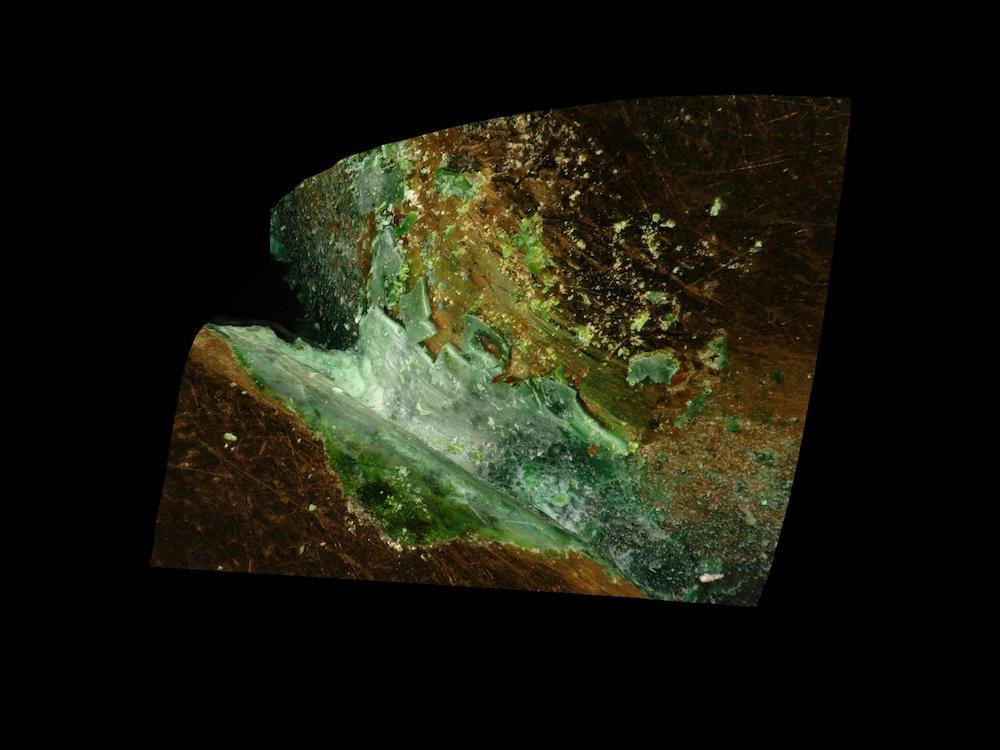

The process of making hand-crafted gold jewellery includes the melting of gold with a small burner. The goldsmith may then use tools such as tweezers to pick out the gold and place it in acid and water. The craftsmen would further shape and carve the gold in accordance to specific designs as requested by customers. Some craftsmen may choose to draw the design on a gold bar before carving the customised shapes.

Goldsmiths are almost always male and businesses are family-run, with the trade usually passing from father to son or other male kin. In Singapore, however, the owners have had to hire goldsmiths from their native villages in India or through other personal connections, as fewer men are taking up the profession here. Women may help out as sales representatives, but they do not typically take part in the goldsmithing work.

The job involves long hours, with the goldsmith working 10 to 12 hours daily, six days a week. Traditionally, he sat cross-legged on a floor mat, bent over a small bench to work. Today, he sits on a stool and works at a table. A goldsmith’s space is sacred and no footwear is allowed. All goldsmiths wear the poonal (a sacred thread).

The goldsmith is known for making the thaali, a gold chain with a pendant that is given by the groom to the bride as a marriage rite. Before making the thaali, the goldsmith offers prayers with a spread of vegetarian food to the customer’s family deity to bless the gold that will be used. A picture of the deity is propped up in front of the goldsmith while he makes the thaali. The thaali is collected by the customer during an auspicious time.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Kasinathan has been a goldsmith since he was 18 years old. He learnt the trade from his father back in Chettinad, Tamil Nadu, India. Mr Kasinathan arrived in Singapore around 1991 and started working as an apprentice goldsmith at a shop in Little India. He set up his own shop in 2008. His customers come from all ethnicities and religions.

Mr Kasinathan and his employee, Mr Thiyagarajan Kalyana Sundaram, do the same work, while Mr Kasinathan’s son-in-law works on repairing costume jewellery. Occasionally, Mr Kasinathan’s daughter and granddaughter help with customer service. Mr Kasinathan does his goldsmithing work entirely by hand. The processes he uses in his trade are similar to those of traditional goldsmiths in India, he says. He believes that handcrafted jewellery lasts longer than machine-made pieces. “If machine-made jewellery lasts for a year, handcrafted jewellery can last up to 10 years,” he says.

Present Status

Hand-crafted gold jewellery by Indian goldsmiths have dwindled over the years, as the production of such jewellery has increasingly been mechanised. Despite this, efforts have been made to promote knowledge and awareness of the trade in Singapore.

Mr Kasinathan feels that there are still ways to support the trade, though the number of goldsmiths and potential goldsmiths are dwindling. "If we don’t want this trade to diminish, we need to gather professionals in this trade and create an association and give a boost to this profession,” he says. “This profession has never disappointed those who have kept their faith in it. It is a good profession.”

References

Reference No.: ICH-041

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Battacharya, J. “Beyond the glitterati: The Indian and Chinese Jewelers of Little India, Singapore”. In J. Bhattacharya (ed.), Indian and Chinese immigrant communities. London; New York: Anthem Press, 2015.

Lo-Ang, S. G., & Huan, C. C. Vanishing trades of Singapore. Singapore: Oral History Department, 1992.

Siddique, S., and Shotam, N. L. Singapore’s Little India: Past present and future. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982.

Sullivan, M. “Can survive, la”: Cottage industries in high-rise Singapore. Singapore: Graham Brash, 1993.

Zaccheus, Melody. “Veteran goldsmith keeps tradition glowing in Little India”. The Straits Times, 16 March 2013.