The Empress of Asia was originally a luxury ocean liner. She was launched in 1912, one year after the Titanic. Both ships were similarly fitted out, from portholes to toilets to glistening silverware. She was requisitioned as a troop carrier during WWI, and then again in WWII.

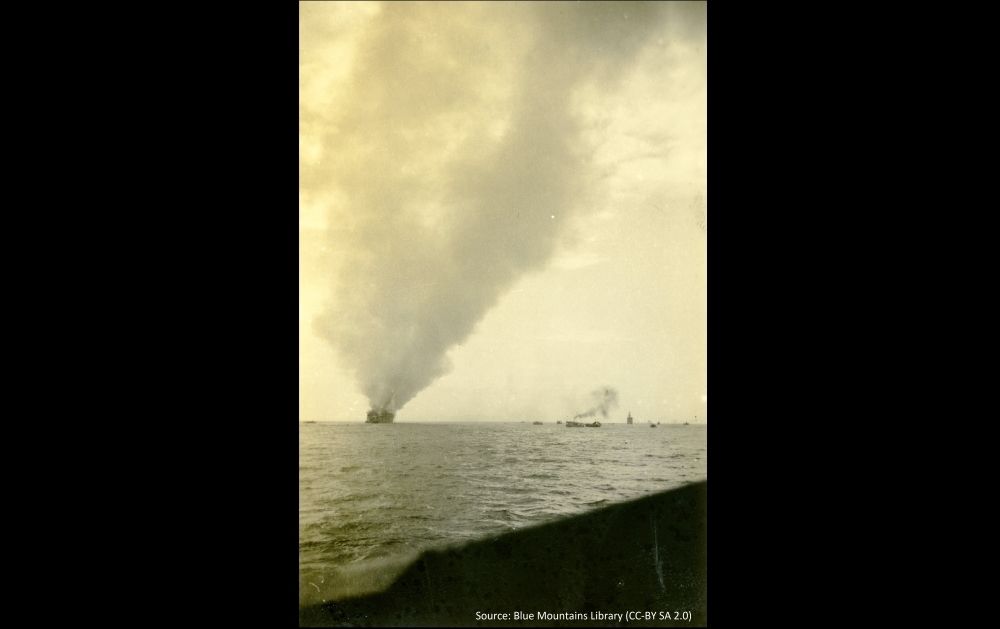

The Empress of Asia was attacked by Japanese bombers on 5th of February 1942, on the final leg of her voyage from Bombay to Singapore. She was carrying a large contingent of British troops who were desperately needed to bolster Singapore’s defences. Remarkably, the troops and crew all made it to shore, having abandoned their sinking ship off Sultan Shoal Lighthouse. Just ten days later, most were declared Prisoners of War when Singapore surrendered to Japan.

The fire ravaged capsized hull was partially salvaged after the War. The remnants were removed in 2020 to ensure navigational safety at Tuas Port. The wreck structure was documented by the National Heritage Board and a fascinating array of artefacts was recovered for research, conservation and display.

Source: Blue Mountains Library, Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Attack

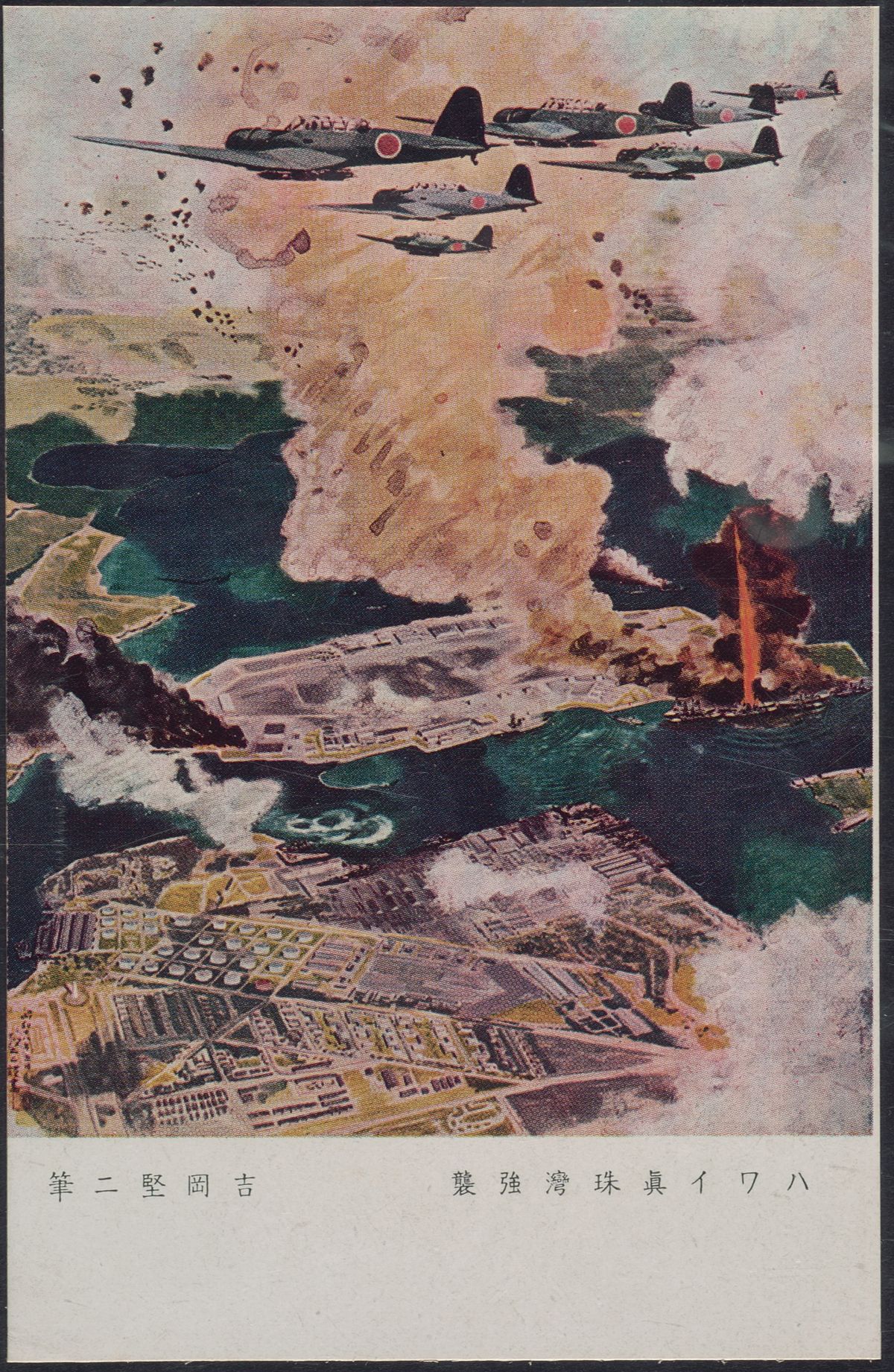

The Japanese invasion of Singapore commenced on the 8th of February 1942. Just three days earlier, the final elements of the British Army’s 18th Infantry Division arrived from Bombay in five troop carriers traveling in convoy. Not all troops disembarked in an orderly manner.

At 11 a.m. on the 5th of February the convoy came under attack as it entered Singapore Strait from the west. Japanese planes swooped in from all directions and altitudes, focusing their attention on the largest ship, the RMS Empress of Asia. She endured an hour of bombardment, taking three direct hits. Fire engulfed the entire superstructure, from the bridge to the aft funnel. Chunks of burning debris dropped into the smoke-filled engine room, forcing the engineers and firemen to retreat.

Taking advantage of the ship’s dwindling momentum, Captain A B Smith swung the Empress of Asia towards the Sultan Shoal Lighthouse. Smoke and heat forced the officers to evacuate the bridge by sliding down a rope to the foredeck. The Captain was the last to leave, after throwing a steel box containing confidential documents into the sea. On reaching the deck, he gave the instruction to let go the anchor, for the last time.

Abandon Ship

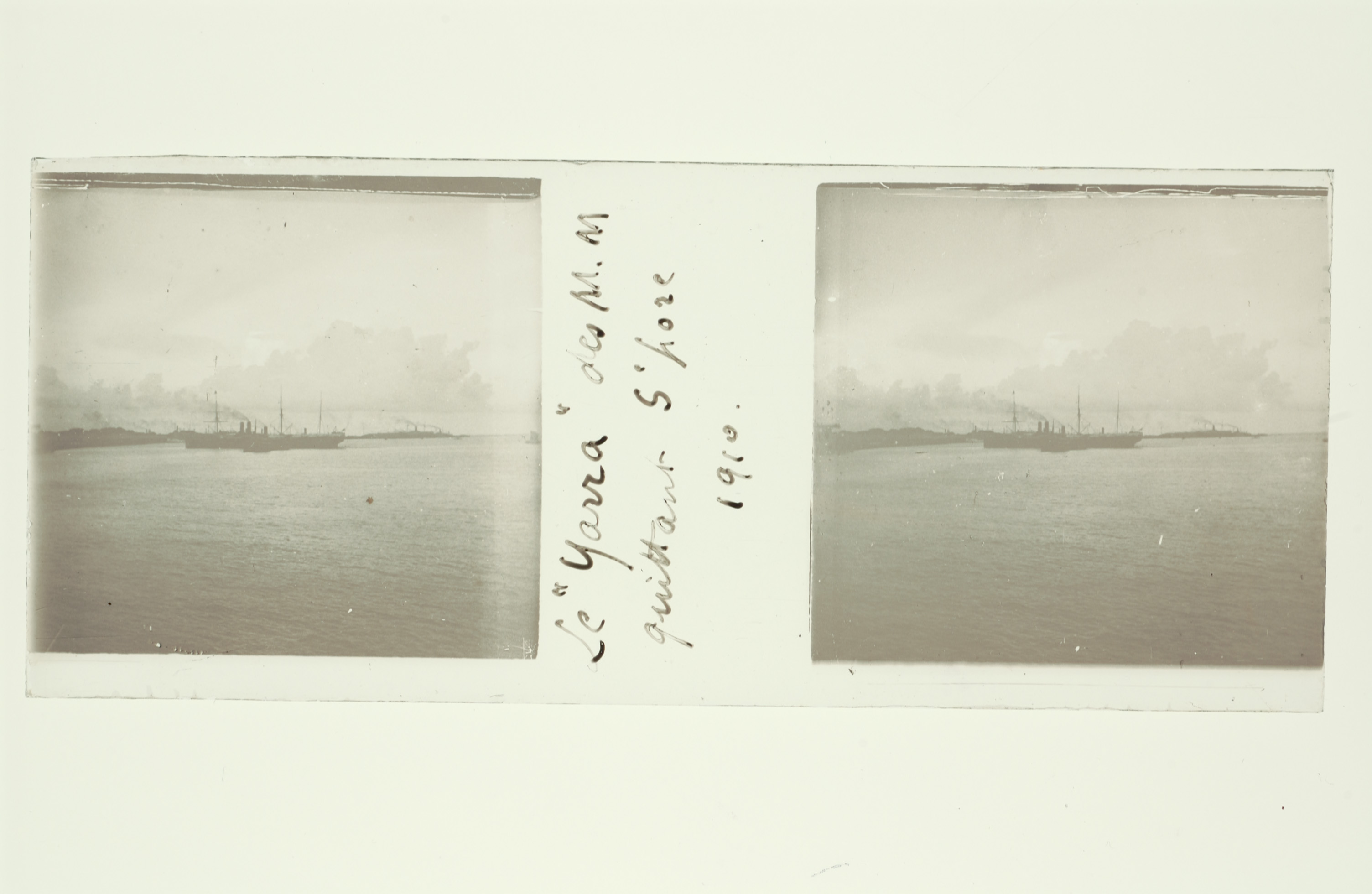

Only the bow and stern remained undamaged and clear of smoke. The 2,235 troops who were mostly sheltering below deck joined the 415i ship’s crew at the crowded extremities. The lifeboats were either ablaze or enveloped in smoke. Japanese planes were still flying overhead, but shortly past noon, they dispersed and small craft began coming alongside to rescue the personnel. A large number landed on the Sultan Shoal, only 500 metres away, with boats returning to the ship to pick up the next batch. The sloop Yarra rescued over 1,000 troops and crew from the stern. By 1 p.m., all personnel had been evacuated. In Captain Smith’s words, “Everyone behaved very well indeed. There was no panic, the troops were splendid, and everyone did their job.”ii

While not mentioned by the Captain, many personnel jumped into the sea before the rescue boats appeared. Singapore police boat commander Pestana reported picking up dozens of people, with “those who could swim declining to get into the launch to make way for non-swimmers”.iii Machine-gunner, Bill Moylon, related how he had to jump from a great height to avoid being overwhelmed by acrid smoke, in an interview recorded in his 98th year.iv From a compilation of stories from the 125th Anti-Tank Regiment, “One A.A. team from the Regiment actually jumped from their gun position on the 'fiddley-deck' into the sea after they were cut off. All men forward had to leave the ship down a 60 ft rope into the water.”v Sam Purvis, a military nurse with an injured knee, squeezed out of a porthole and shinned down a rope that was suspended from the rail above. He could not swim but managed to grab the handle of an inflatable raft.vi

Mopping Up

After the evacuation was completed, Captain Smith boarded HMS Sutlej and made a wide sweep round the burning hulk to make sure that no one had been overlooked by the rescue craft. If the newspaper reports were correct, he missed three. Pestana plucked them from the water while continuing his search that night.

The Captain proceeded to Keppel Harbour, finally stepping ashore at 8 p.m. The following day, Friday the 6th of February, 127 firemen and one steward from the Empress of Asia joined two transport ships that were leaving Singapore. They were the lucky ones. The remainder of the crew were taken to a military camp. Captain Smith attempted to ascertain casualties:

“On Saturday, 7th, I learned from OC [Officer Commanding] Troops that a check had been made and only 15 of his men were not accounted for but he pointed out that some of these men might have got adrift in the town after landing and might yet turn up. The only known casualty to my crew was D Ellsworthy, a Canadian Pantryman, who died in hospital from injuries and was buried in Singapore.”

At least seven military personnel eventually succumbed to injuries sustained during the bombardment.vii These soldiers are commemorated at the Kranji War Memorial. Crewman Ellsworthy is buried there. At least eleven other crew members, and many of the transported troops, lost their lives during the course of the War. Remarkably, not one of the 2,650 people on board went down with the ship. The Empress of Asia is not a war grave.

Prisoners-of-War (POWs)

Some 133 members of the Empress of Asia’s catering and medical crew continued to contribute to the war effort by serving at the General and Miyako Hospitals in Singaporeviii, where they looked after their injured shipmates, amongst the many others. With the surrender on the 15th of February, they were all interned as Prisoners of War at the Changi and Sime Road camps. Other personnel from the Empress of Asia were captured while attempting to flee Singapore for areas still under Allied control. Those captured outside Singapore were held at various locations, including Sumatra, Java, Thailand, and Malaya.

One extraordinary Empress of Asia survivor is Corporal Ras Pagani. After the Allies surrendered, he escaped from Singapore to Sumatra in a small boat and ‘eventually fetched up at Padang’. While repairing a steam tug to make a bid for Ceylon, he and some mates were taken prisoner by the Japanese. After two months, he was shipped to Mergui with 500 others where he was put to work offloading ships and constructing airfields. He was then shifted to the dreaded Burma-Siam railway near Moulmein. He escaped and made his way in a roundabout fashion towards distant Arakan where British forces were stationed. Although he was much assisted by Karen and Burmese groups, he was finally betrayed while crossing the Irrawaddy River, shot and handed over to the Japanese. To avoid certain execution as an escapee, Pagani claimed to be a downed American airman. He was believed and saw out the war as a POW in Rangoon.ix

History of the Ship

The Empress of Asia was built by Scottish company Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering at Govan, on the River Clyde, just downstream from Glasgow. She was launched in 1912 and fully fitted out by May 1913. At 180m long and 20 m widex, she was a mid-sized liner typical of others in the fleet of the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company (CPS). CPS was fully owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and therefore could offer a through service for passengers and mail from Britain to Asia, via railway across Canada.

The Empress of Asia was requisitioned by the British Admiralty at the outbreak of WWI, just over a year after commencing scheduled voyages between Victoria in western Canada and various Asian ports. In August of 1914, she was converted into an auxiliary cruiser with the installation of eight 4.7-inch guns. She was assigned blockade and convoy escort duties from the South China Sea to the western Indian Ocean. The liner returned to commercial service for two years, but in April 1918 she was again requisitioned, this time by the Canadian government to transport American troops to Europe. After the Armistice she carried Canadian troops home. The Empress of Asia resumed the trans-Pacific mercantile trade in February 1919 after a quick refit.xi

Over 20 years later, the Empress of Asia was again requisitioned by the British Admiralty, this time for WWII service. She sailed from Vancouver for Britain on February 13th, 1941, via the Panama Canal. The onward voyage was by way of Jamaica and Bermuda, reaching the Firth of Clyde in Scotland in late March.xii After a brief interlude she sailed for Liverpool where modifications for troop carrying duties were undertaken. Accommodation and cooking facilities were expanded, and armaments added, including one 6-inch gun, a 3-inch AA gun, 6 Oerlikons, 8 Hotchkiss, 4 PAC rockets, and a rack of depth charges. The refit was completed by the end of April.xiii

Her first task was to transport 2,000 soldiers of the Green Howards to Suez via the Cape of Good Hope to participate in the North Africa Campaign. From the Red Sea, she took Italian prisoners of war to Durban. In September 1941, the Empress of Asia sailed with the first convoy from North America to England, escorted by ships of the United States Navy.xiv

Her Final Voyage

After embarking troops, the Empress of Asia sailed from Liverpool for Africa on November 12th, 1941, reaching Freetown on November 26th. While enroute to Capetown, Pearl Harbour was attacked, escalating the war into Asia and the Pacific. Christmas Day was spent at Durban where orders were received to disembark the troops on board and to proceed directly to Bombay. She reached Bombay on January 15th, 1942, embarked a new complement of troops and set sail for Singapore in convoy a week later.xv

The convoy proceeded across the Indian Ocean to the Sunda Strait, where some ships broke off for Batavia (Jakarta). The rest steamed north towards Bangka Strait. While passing through this narrow waterway, a formation of Japanese planes bombed the convoy from high altitude.

The Empress of Asia recorded five near misses, with one bomb exploding only 3 m from the hull. Shrapnel pierced two of the lifeboats and white-water cascaded down onto the decks. On the afternoon of 4th February, two of the faster ships left the convoy in order to reach Singapore first thing the next morning. The remaining ships, including the Empress of Asia reached the western reaches of Singapore Strait later in the morning of the 5th. That’s when the next fatal wave of bombers struck.xvi

Salvage

When inspecting his command two days after the attack, Captain Smith observed, “I do not think there is much chance of the Japanese salvaging the ship.”xvii The fire had by then spread to the coal bunkers and intensified. While extensively ravaged, the Empress of Asia had not yet sunk. The First Officer of the SS Kedah, Lieutenant Commander Allen, noted that on reaching Singapore on the morning of February 11th, they passed the “burned-out shell of the Empress of Asia”, suggesting that she was still afloat six days after the attack.xviii Soon afterwards, however, the hulk must have capsized and sank with her port-side down. The starboard side remained awash in 18 m of water. Red lights were later affixed as she was deemed to be a navigation hazard.

The Japanese didn’t salvage the Empress of Asia during the War, but, just eight years after surrendering, they were back in Singapore offering to raise the ship. Mr Kuwabara, president of one of the biggest salvage companies in Japan, Matsukura and Company, told the Straits Times in December 1953 “it could be raised easily”, along with other wrecks in the harbour and the wrecks of the HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales off the east coast of Malaysia.xix The Singapore licensed salvor, the International Salvage Company, signed a contract with Matsukura in February 1954, pending the arrival of 160 Japanese salvage experts.xx Matsukura also offered to buy all of the scrap for shipment to Tokyo. But local outrage at Japanese participation scuttled their efforts.

The Straits Times first announced that the salvage of the Empress of Asia and various other wrecks would commence in February 1952.xxi The newly established International Salvage Company (Malaya) Ltd. erected a wooden platform on the partly exposed hull for the deployment of a generator and other equipment. In September, three men were arrested for stealing the generator.xxii

A light-hearted piece in the Straits Times of the same month describes the camp built by the salvage crew on Pulau Sakra.xxiii “These men have come from Hongkong and a tougher and yet more personable set of men would be hard to find. Obviously, they take great pride in their skill and know the meaning of teamwork. They have built themselves a jovial camp, each hut in the shade of its own site with little paths neatly bordered in places with a patch of flowers or vegetables. But ask before you land.”

Apart from the abortive Japanese foray into the Singapore salvage business, there is no more reporting on the Empress of Asia until January 1957. In the preceding years, the International Salvage Company had successfully cut up and removed six wrecks, along with “thousands of tons of metal” from the Empress of Asia.xxiv Now divers were continuing the work. In October of 1957, the Straits Times announced that blasting operations had begun. Indeed, a series of Singapore Notices to Mariners every year through to 1961, warned passing shipping that blasting and salvage operations would be taking place at the wreck site.

Recent Recoveries

In July 1998, a private diving group calling themselves Technical Diving International – Asia recovered a range of artefacts from the Empress of Asia, including a 4-tonne anchor, a rusted machine-gun, porcelain, and a candlestick holder. The artefacts were donated to the then Singapore History Museum.

In 2015, a seabed debris survey, undertaken as part of preliminary works for the Tuas Mega-Port development, reconfirmed the charted wreck location off Sultan Shoal for subsequent salvage works. The position corresponded to that recorded for the Empress of Asia on 19th March 1946 in an Admiralty Notice to Mariners: 01⁰ 14’ 09” N, 103⁰ 39’ 09” E. The 1966 edition of Admiralty Chart 3836 depicts the wreck in the same location, to the southeast of Sultan Shoal with her bow heading west-northwest.

This Admiralty Chart indicates that the wreck dries 6 feet (1.8 m) at low tide and lies in 10 fathoms (18.3 m) of water. However, by 1966 the wreck didn’t dry at all due to the extensive salvage works. The shallowest depth of the wreck was updated regularly and charted over the years. The 2015 multi-beam sonar image clearly showed that the shallowest point was around 11 m deep with a series of parallel lines punctuating a long mound of sediment. During an archaeological diving survey carried out in early 2016 by the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS), on behalf of the National Heritage Board, it was confirmed that the lines were the edges of decks fully exposed after the removal of the starboard hull plating. Furthermore, some 50 metres of the bow, almost all the superstructure, all the boilers and turbines, and much of the keel were now missing. Well over half of the ship had been salvaged, and the exposed remnants were severely corroded.

The wreckage lay within the navigation channel for the upcoming Tuas Port. Wreck removal proceeded with NHB and ISEAS personnel documenting identifiable structural elements and recovering historically significant objects for research and conservation.

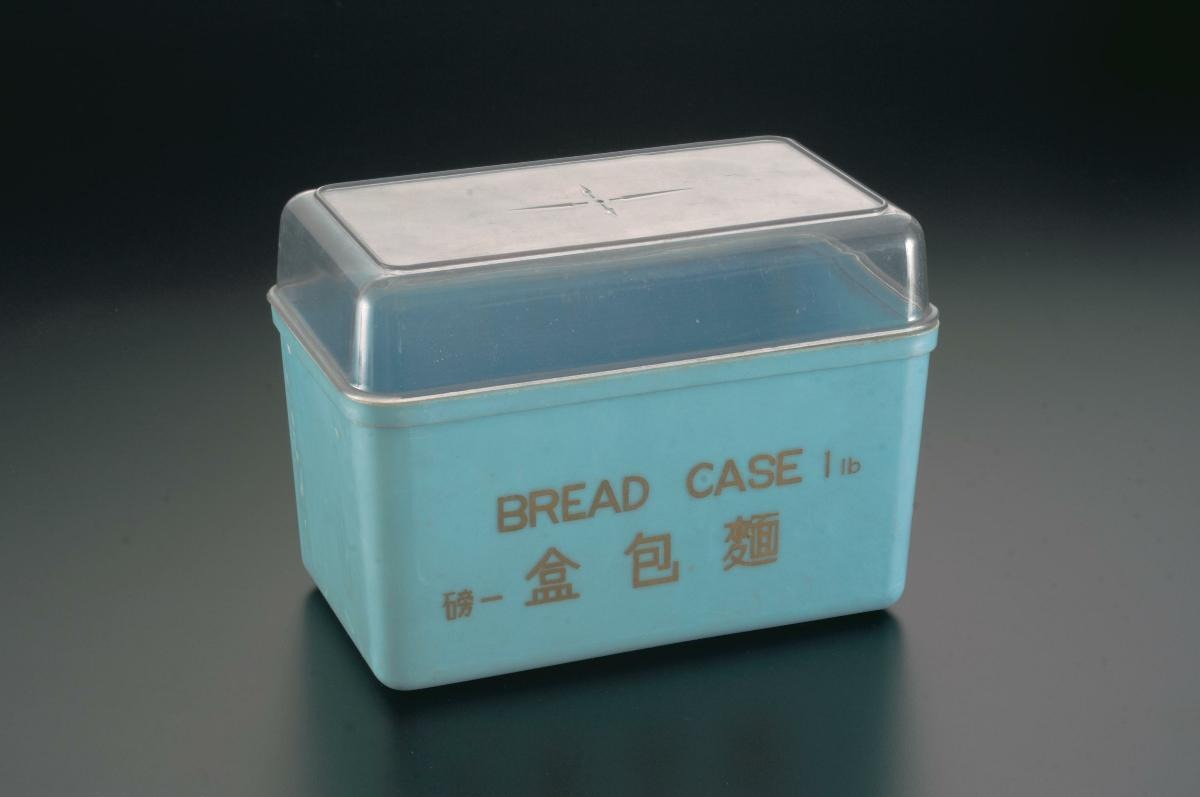

These include structural fittings such as portholes, valves and davits, and cabin fixtures such as taps, wall lamps and doorknob assemblies. There are the accoutrements of fine dining such as silverware cutlery and trays, along with porcelain cups and dishes. These artefacts are linked to the ship and her colourful history since she was launched in 1912.

Artefacts Tell The Story

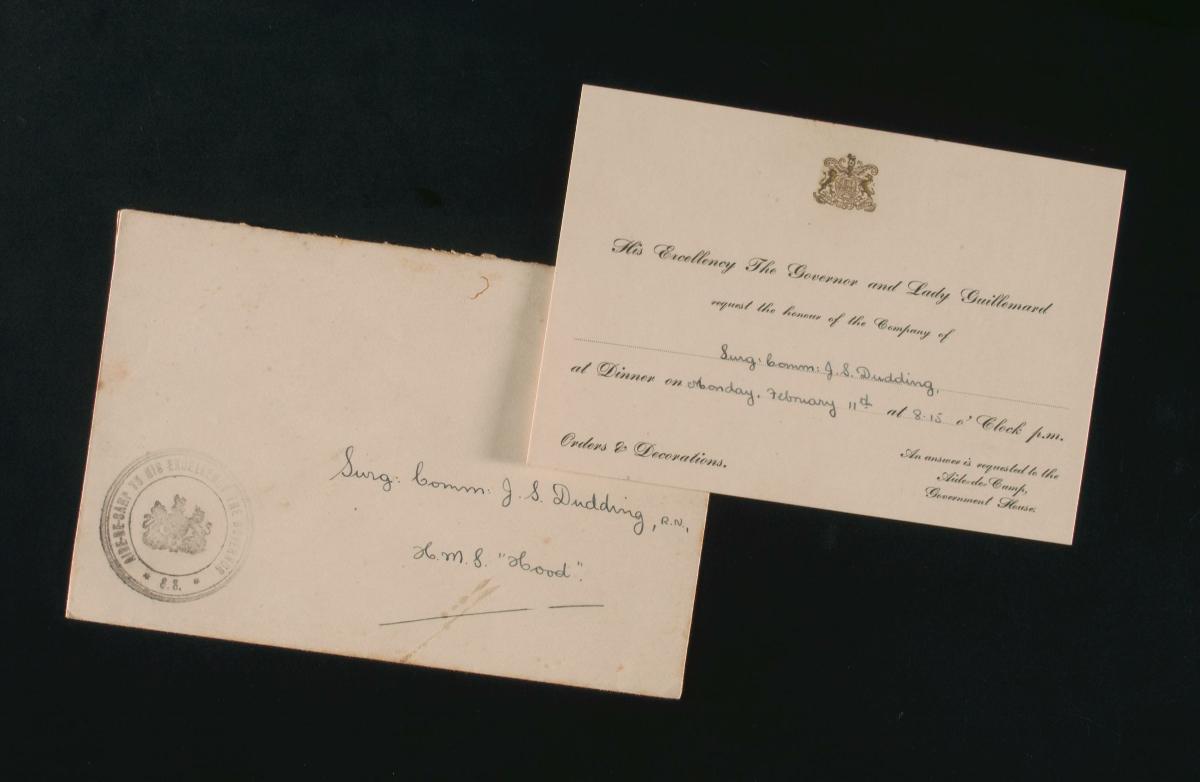

The NHB engaged in discussions with the UK Foreign Commonwealth Office and the Department for Transport, in recognition of the UK Government’s ownership of the vessel and its artefacts. Selected artefacts were loaned for an exhibition at the National Museum of Singapore to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore.

The Empress of Asia was one of many luxury ocean liners traversing the oceans during a period regarded as the golden age of travel, at least by first-class travellers. The Titanic was launched only a year earlier than the Empress of Asia. She was built in Belfast, Ireland, a short hop across the Irish Channel from the Govan shipyards. Many companies supplied the same components for the fitout of both ships. Several artefacts from the Empress of Asia are identical to those recovered from the Titanic lying 3,800 metres deep in the tempestuous Atlantic.

Military artefacts recovered from the Empress of Asia include a paraffin blow lamp embossed with a broad arrow, brass webbing and the remnants of Lee Enfield rifles. Stores include glass bottles for beer, wine and condiments. Personal effects such as a pocket watch perhaps belonged to one of the ship’s officers. Military hardware and stores could have been loaded at various ports during the final deployment, from Liverpool to Durban to Bombay. Non-perishables may have remained on board from as far back as the requisition in Vancouver.

These artefacts along with photographs of identifiable hull remains tell the stories of the last journey of the Empress of Asia. The Empress of Asia will not be forgotten.

Notes

i In Bombay 416 crew embarked, however one died en route to Singapore.

ii https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/ss-empress-of-asia

iii Straits Times 6th March 1960 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19600306-1.2.38) and Straits Times

iv https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQaF1cLVywY&t=232s (17th September 2014)

v https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/125th-anti-tank-regiment-royal-artillery

vi https://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/Mister_Sam/html/empress_of_asia.htm

vii http://www.empressofasia.com/

viii http://www.empressofasia.com/

ix Straits Times 22nd December 1946 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19461222-1.2.63)

x From the 1939 Canadian Pacific Deck Plans for the Empress of Russia and the Empress of Asia (https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/chung/chungosgr/items/1.0216170)

xi http://www.empressofasia.com/

xii http://www.empressofasia.com/

xiii https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/ss-empress-of-asia

xiv http://www.empressofasia.com/

xv http://www.empressofasia.com/

xvi This is from the account of Captain Smith (https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/ss-empress-of-asia). For another detailed account of the voyage to Singapore see: https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/125th-anti-tank-regiment-royal-artillery

xvii https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/ss-empress-of-asia

xviii Straits Times 18th September 1946 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19460918-1.2.44)

xix Straits Times 5th December 1946 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19531205-1.2.33)

xx Straits Times 27th February 1954 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19540227-1.2.71)

xxi Straits Times 23rd February 1952 (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19520223-1.2.101)

xxii Straits Times 5th September 1952 (http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19520905-1.2.131)