Kreta Ayer Heritage Gallery

Kreta Ayer Heritage Gallery provides an overview of the history and heritage of Kreta Ayer, and highlights the area’s rich and diverse intangible cultural heritage. These include cultural art forms such as Chinese opera, Chinese puppetry, nanyin music, tea appreciation and calligraphy.

Through photographs, stories and objects from the community, this gallery showcases the rich cultural heritage of the Chinese community in Chinatown. Step into the Kreta Ayer Heritage Gallery to find out more about the above-mentioned cultural art forms and trace their evolution from the days of old Chinatown to contemporary times.

Kreta Ayer Heritage Gallery – Introduction

Watch: Introduction to Kreta Ayer

What is intangible cultural heritage?

Under the 2003 UNESCO Convention for Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is defined as cultural practices and living traditions which reflect cultural diversity and creative expression, and provide communities with a sense of belonging.

In Singapore, ICH can be broadly classified into six categories: oral traditions and expressions; performing arts; social practices, rituals and festive events; knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; food heritage; and traditional craftsmanship.

ICH is part of our living heritage and continues to evolve with time. ICH fosters a sense of identity amongst the different communities and contributes to the vibrancy of Singapore’s multicultural heritage. It is therefore important that we document and safeguard our ICH for future generations.

1828

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Kreta Ayer: Cultural Heartland of Chinatown

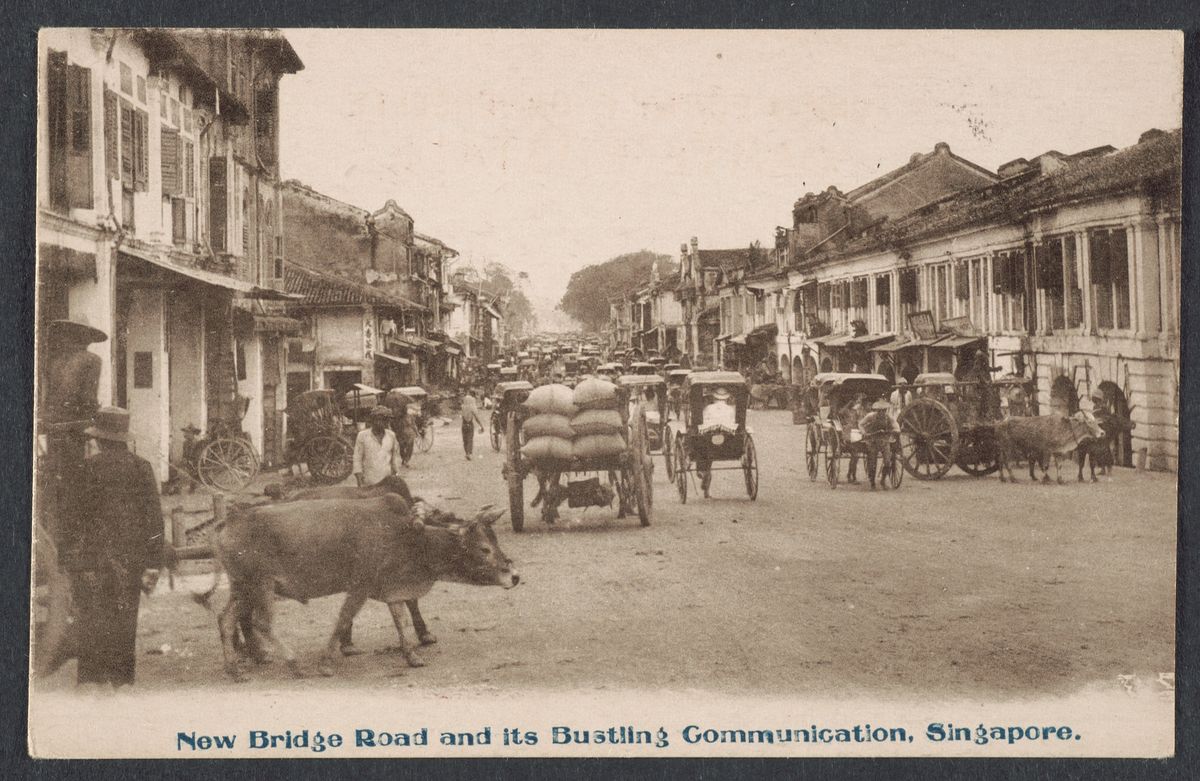

The boundaries of present-day Chinatown were established in 1822 and its origin can be attributed to Sir Stamford Raffles. This is because Raffles organised the town of Singapore according to ethnicity as a way of preserving communal harmony, as well as facilitating trade by locating ethnic groups involved in commerce closer to the port. The historic district of Chinatown today consists of four sub-districts: Telok Ayer, Kreta Ayer, Tanjong Pagar and Bukit Pasoh.

Among the four sub-districts, Kreta Ayer Road and its neighbouring streets formed the commercial heart of Chinatown. The name “Kreta Ayer” means “water cart” in Malay, which refers to the bullock and ox carts that plied Kreta Ayer Road in the mid-1800s. These carts were used to distribute water from wells located in Ann Siang Hill.

The early immigrants of Kreta Ayer, who were predominantly Cantonese, brought with them traditional and cultural traits from their hometowns in China. Kreta Ayer soon became a cultural heartland known for its concentration of teahouses and opera theatres. It was also home to other traditional arts such as nanyin music, lion dance and wushu, which are examples of ICH that are still practised in Chinatown today.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Chinese Opera

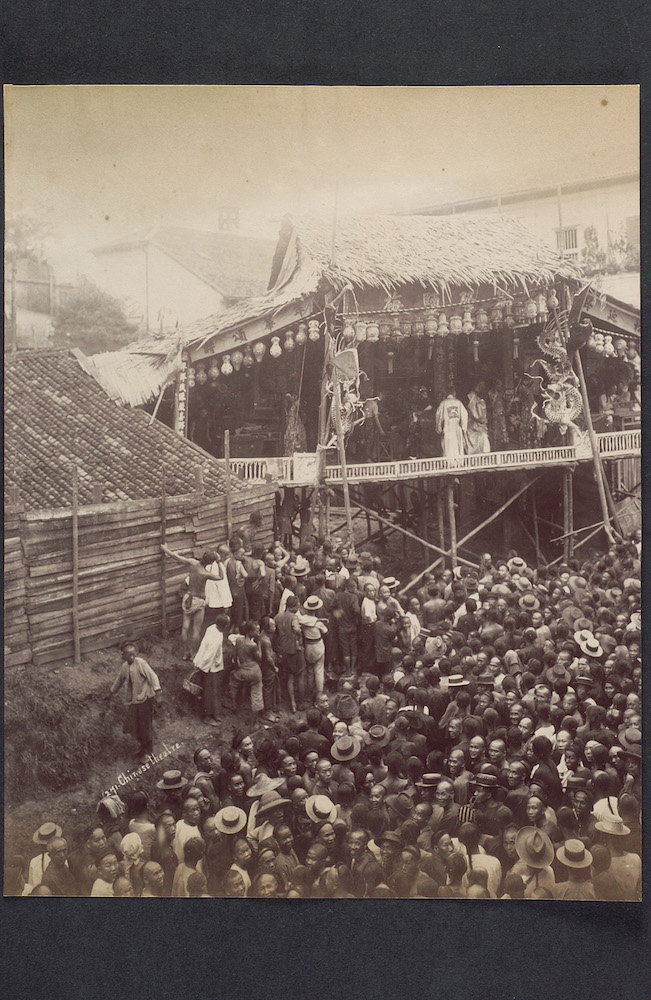

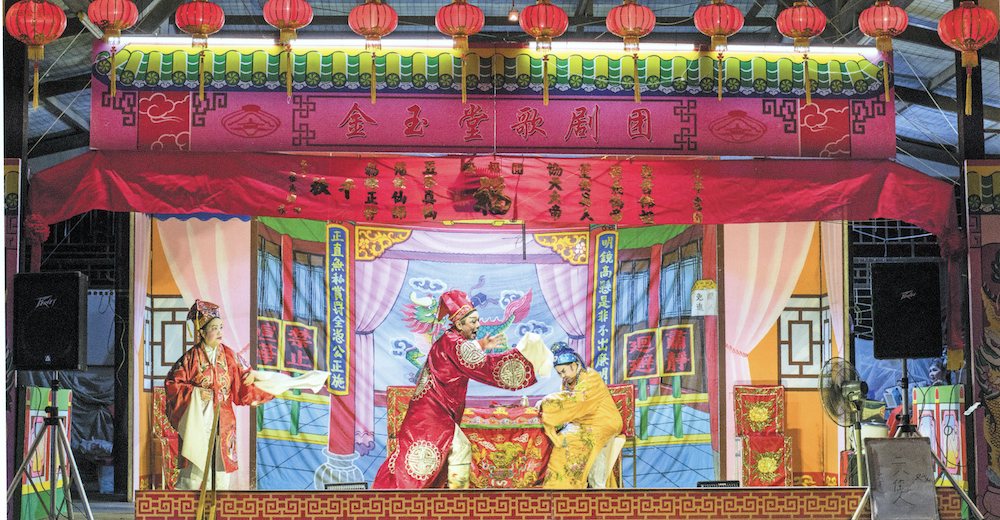

Chinese opera is a performing art form rooted in Chinese tradition and staged with stylised actions and elaborate costumes. Music, acting, martial arts and acrobatics are key features across various genres of Chinese opera. Opera performances often draw upon Chinese folklore, history or literature, and showcase aspects of Chinese culture, tradition and philosophy.

Known locally as “wayang” in Malay, Chinese opera was the most popular form of local live entertainment for more than a century in Singapore. Introduced by Chinese migrants in the 19th century, it was often performed at religious festivities in honour of deities such as Ma Zu (goddess and protector of seafarers), Guan Yin (goddess of mercy) and Guan Di (god of war and protector of tradesmen). Presented on makeshift stages, opera performances were often sponsored by temples and clans, and staged for free public viewing.

Between the late 1800s and 1930s, the Chinese opera scene in Singapore was thriving and the 1881 census recorded a total of 240 Chinese opera performers. In fact, Chinese opera became so popular here during its heyday that Singapore was known as the “second homeland of Cantonese opera” outside of Hong Kong and China!

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Paul Piollet Collection, courtesy of National Heritage Board

Replicas of Joanna Wong’s collection

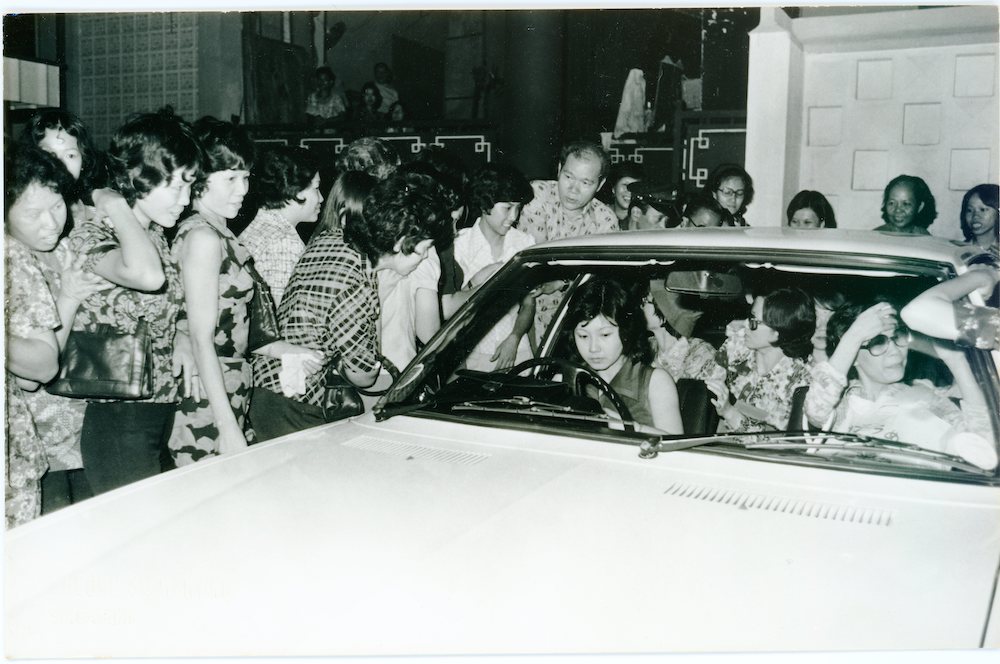

These photographs were taken after a performance by the famous Hong Kong Chor Fung Ming Cantonese Opera Troupe at Kreta Ayer People’s Theatre in 1975. As evidence of the popularity of Chinese opera during that time, throngs of enthusiastic fans could be seen surrounding the performers as they leave the theatre.

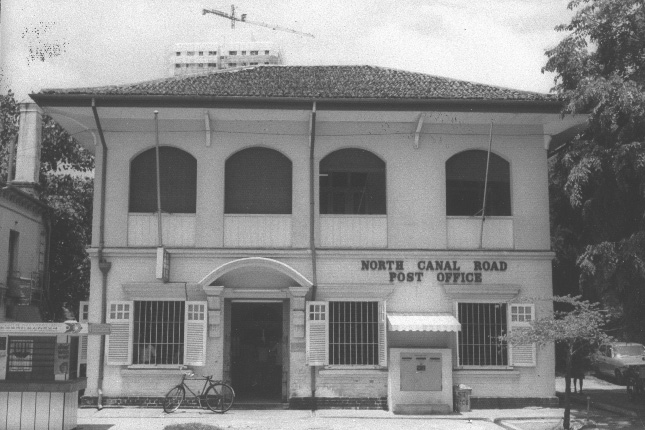

Opera Houses

As the popularity of Chinese opera increased, opera houses that could accommodate hundreds of patrons were built in Chinatown to stage shows on a daily basis. Established in 1887 along Smith Street, Lai Chun Yuen was the first opera house dedicated to Cantonese opera and staged performances twice a day. Other notable opera houses include Heng Seng Peng and Heng Wai Sun at Wayang Street (today’s Eu Tong Sen Street).

Another well-known venue is Tien Yien Moi Toi Theatre (former Majestic Theatre), built in 1927 by tycoon Eu Tong Sen, reportedly for his wife who was an avid opera fan. In the early years of its inception, it attracted glamorous opera stars from China before it was converted into a cinema in 1938.

In the early 20th century, Chinese teahouses were also popular venues for opera performances. The teahouse at Great Southern Hotel, colloquially known as Nam Tin, drew crowds with regular qingchang (Mandarin for “pure singing”) performances which involve solo or group renditions of operatic excerpts accompanied by a small group of musicians.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Bels Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Phan Wait Hong Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Elements of Chinese Opera

Costumes

In general, Chinese opera costumes can be divided into five categories, namely mang (four-clawed dragon robe), pei (informal robe for the elite), kao (armour), zhe (robe for commoners) and yi, (other costumes).

The costumes help audiences identify the role of each character, whose social standing is reflected in the costumes. Costumes with more elaborate designs are typically worn by important and powerful figures while simpler ones are reserved for those with a low status. Most costumes make reference to clothing from historical periods such as the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), which was the golden era of Chinese opera.

Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam

Music

Music in Chinese opera can be divided into two categories: wen (Mandarin for “civil”) and wu (Mandarin for “military”). Wen music comprises string and wind instruments that accompany characters such as scholars and court ladies. Wu music uses percussion instruments in dramatic moments such as hand-to-hand combat and battle scenes.

Characters

Characters in a Chinese opera are generally classified into four types: dan (female characters); sheng (male characters); jing (male characters with painted faces); and chou (clown). Each character type has its own distinct make-up, costume and performance style. Typically, a performer would specialise in a specific role and refine his or her portrayal of the character over time.

Courtesy of Dr Yam Tim Wing

Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam

Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam

Courtesy of National Heritage Board

Courtesy of National Heritage Board

This is a typical costume worn by an actor playing a male general during battle scenes in a Chinese opera performance. The body of the costume is usually covered in scale-like motifs, which are modelled after ancient Chinese amour. The four triangular flags attached to the back of the costume are a reference to pennants of command awarded to generals in the past. They also symbolise preparedness for war, and heightens the costume’s dramatic effect. The flags can be removed after the battle scene is completed.

Kao is also worn by an actor playing a female general during battle scenes in a Chinese opera performance. Compared to the male general’s costume, female kao costumes tend to incorporate a shoulder cape and more feminine touches such as tassels.

Local Dialect Forms of Chinese Opera

Cantonese opera, Hokkien opera and Teochew opera were and remain the three most common regional forms of opera staged in Singapore. The different genres of opera could be found in different quarters: Cantonese opera was predominantly performed in Kreta Ayer, Hokkien opera in the vicinity of Nankin Street and Hokien Street, and Teochew opera around Merchant Road and New Market Road.

Cantonese Opera

Cantonese opera (yueju) is performed in the Cantonese dialect and one of its key characteristics lies in its elaborately embroidered costumes that showcase strong regional influence from Guangdong. The costumes are usually made of silk and satin, and dyed in bright colours that have symbolic meanings. For example, yellow represents respectability, red embodies integrity, and black denotes forthrightness.

Performers also don simple but striking make-up, paired with a bright red lipstick. While most opera genres feature the common “white and red face”, Cantonese opera tends to emphasise the red highlights around the eyes and on the cheeks, as well as a sharp contouring of the nose.

Courtesy of Dr Chua Ee Kiam

Courtesy of Quek Tiong Swee

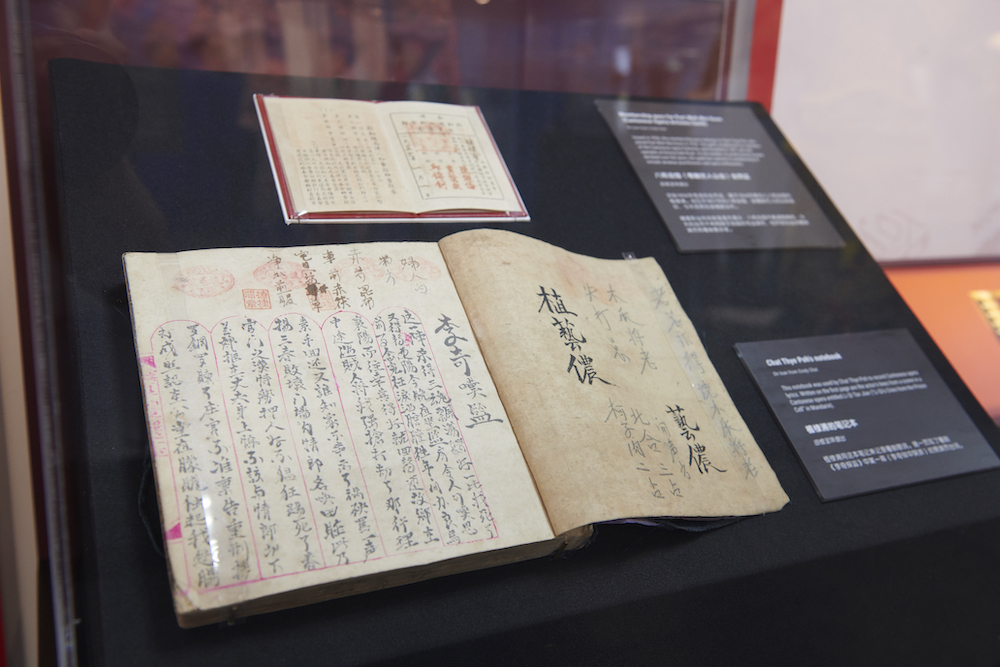

On loan from Cindy Chat

Teochew Opera

Teochew opera (chaoju) is performed in the Teochew dialect and involves colourful costumes and stylised movements. Although the costumes are vibrant and detailed, they are usually not as ornate as their Cantonese counterparts. This genre is also known for its variety of clown (chou) characters, and it is common to see multiple clown characters appearing in a single Teochew opera performance.

Teochew opera is also closely associated with street performances, where a temporary stage is constructed in open areas. These performances are conducted by professional troupes, such as Sing Yong Hoe Heng Teochew Wayang. The oldest of these troupes is Lao Sai Tao Yuan Teochew Opera Troupe, which was established in the 1850s and is the oldest surviving troupe in Singapore.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Hokkien Opera

Hokkien opera (in the form of minju, gezaixi, gaojiaxi, liyuanxi, xiangju) is performed in the Hokkien dialects, and is usually based on folk tales from the Fujian province in China. As most performances are narrated using colloquial language, Hokkien opera is one of the most popular genres of Chinese opera. Folk music (xiaodiao) is also used in performances and such music often possesses a catchy melody, which adds to the genre’s popularity.

Like Teochew opera, Hokkien opera is also associated with street performances. However, unlike its Teochew and Cantonese counterparts, Hokkien opera is known for its improvisation and, in more contemporary times, for using modern musical instruments. One of the most prominent professional Hokkien groups was Sin Sai Hong Hokkien Wayang, which had a history dating back to 1910.

Memories of Chinese Opera

“I became interested in Cantonese opera as a child because I watched opera performances regularly with my aunt. I used to listen to Cantonese operas from my father’s collection of vinyl records and attended singing classes at a clan association. While I never had formal Chinese lessons, I learned to read and write the language on my own by singing and reading opera lyrics.

I was so excited to make my debut as lead actress for Madam White Snake in 1968. I wanted to preserve Cantonese opera, so I set up Chinese Theatre Circle in 1981 with my husband Leslie. We have performed all over the world! I even came up with new ideas like singing opera in English and having English subtitles to help more people appreciate opera. The past 60 years have not been easy, but opera is something I will never give up. My focus now is on nurturing young talent and directing shows.”

– Joanna Wong, whose efforts and achievements in reviving Cantonese opera earned her the prestigious Cultural Medallion in 1981

“My father Chat Thye Poh left China in his teens and first settled in Malaysia, where he trained as an opera apprentice under his mentor. In 1951, he moved to Singapore and made Chinatown his home. He told me that he paid weekly visits to Part Woh Wui Koon (Cantonese Opera Artistes Guild) in Keong Saik Road to seek out potential job opportunities with opera troupe owners.

Over the years, he became a popular Cantonese opera actor skilled in both civilian and military-type roles. He used to travel all over Singapore and Malaysia for work, and performed at different makeshift venues across Chinatown, such as Pagoda Street, Mosque Street and Banda Hill.”

–- Cindy Chat, whose father was a popular Cantonese opera actor in Chinatown in the 1950s and 60s

Chinese Puppet Theatre

Chinese puppet theatre arrived in Singapore from southern China in the late 1800s to early 1900s. Like Chinese opera, Chinese puppet theatre was another form of popular entertainment for the masses. Puppet shows were usually held on a temporary stage, often along the streets or within a temple compound. Occasionally, troupes were also hired to perform for private events such as birthdays or weddings.

Chinese opera and Chinese puppet theatre are closely associated. Like Chinese opera, Chinese puppetry is linked to the Buddhist-Taoist faith and is usually staged to celebrate the feast days of deities. Performers of Chinese puppet theatre were sometimes former opera actors who could employ their singing skills for the puppets’ voices. However, these former opera actors would still need to master the techniques necessary to manoeuver the puppets.

Puppet shows continue to entertain both locals and foreign visitors around Chinatown today, mostly during festive or religious occasions. In an attempt to attract younger audiences, puppet troupes such as Sin Hoe Ping incorporate modern puppets as well as a variety of puppets, such as string puppets and glove puppets, in the same play.

The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings. Reprinted with Permission

Courtesy of Quek Tiong Swee

Common Types of Puppetry in Singapore

In Singapore, the common genres of Chinese puppetry include Hokkien glove puppetry, Teochew iron-stick puppetry, Hainanese rod puppetry and Henghua string puppetry.

The Hokkien glove puppet is between 25 to 35cm in length. The puppeteer controls the puppet’s movements with his hand and fingers, which are fully inserted into the body of the puppet. Only the arms of the puppeteer are exposed on stage, as he controls his puppet from beneath the stage.

The Teochew iron-stick puppet is approximately 35cm in length. Three iron sticks are connected to the puppet: one to support the puppet head made of clay or papier-mâché and the other two for the puppeteer to manoeuver during a performance.

The Hainanese rod puppet measures between 60 to 70cm in length. It has a middle rod which controls the head and two thinner rods at the base for manoeuvring its movements.

The Henghua string puppet is at least 80cm in length and has twelve strings. Additional strings can be attached to perform the trickier and more elaborate movements. At the peak of its popularity in the 1950s, the Henghua genre dominated the Chinese puppetry art scene in Singapore.

Watch: Puppetry Video — An extract from the documentary film Performance of the Gods by Dr Caroline Chia. Courtesy of Caroline Chia and National Heritage Board.

As part of a research and documentation project supported by the National Heritage Board, Dr Caroline Chia documented the history and tradition of Chinese puppetry in Singapore. Completed in 2016, this documentary film was produced as part of her research project.

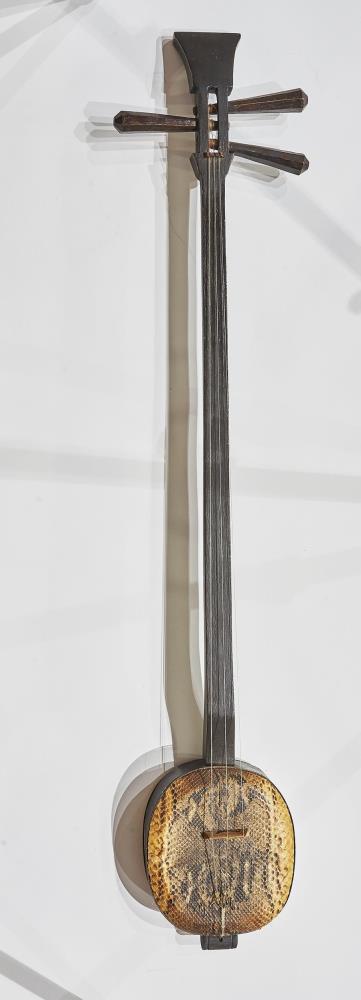

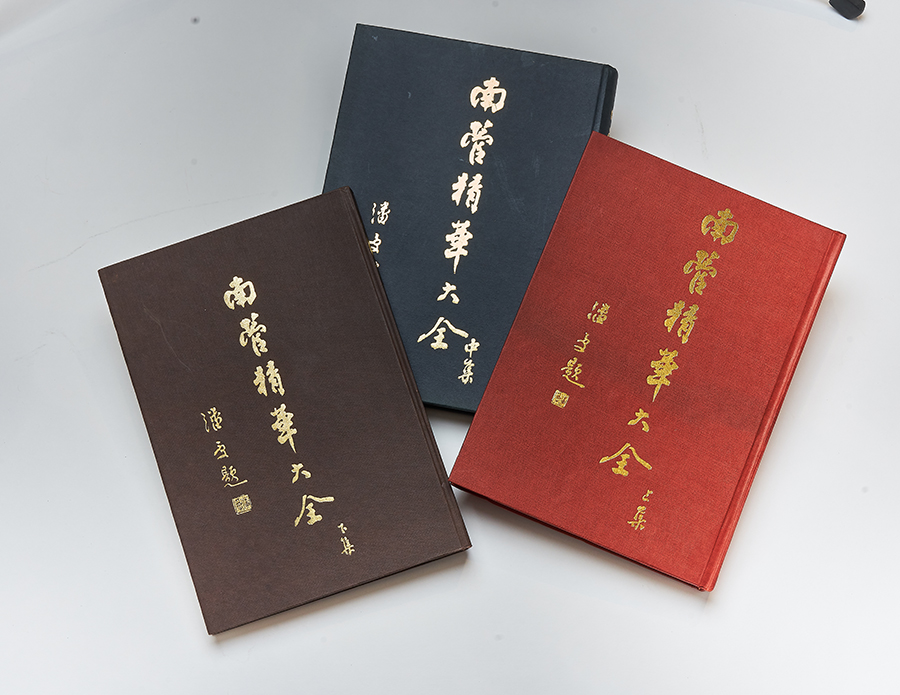

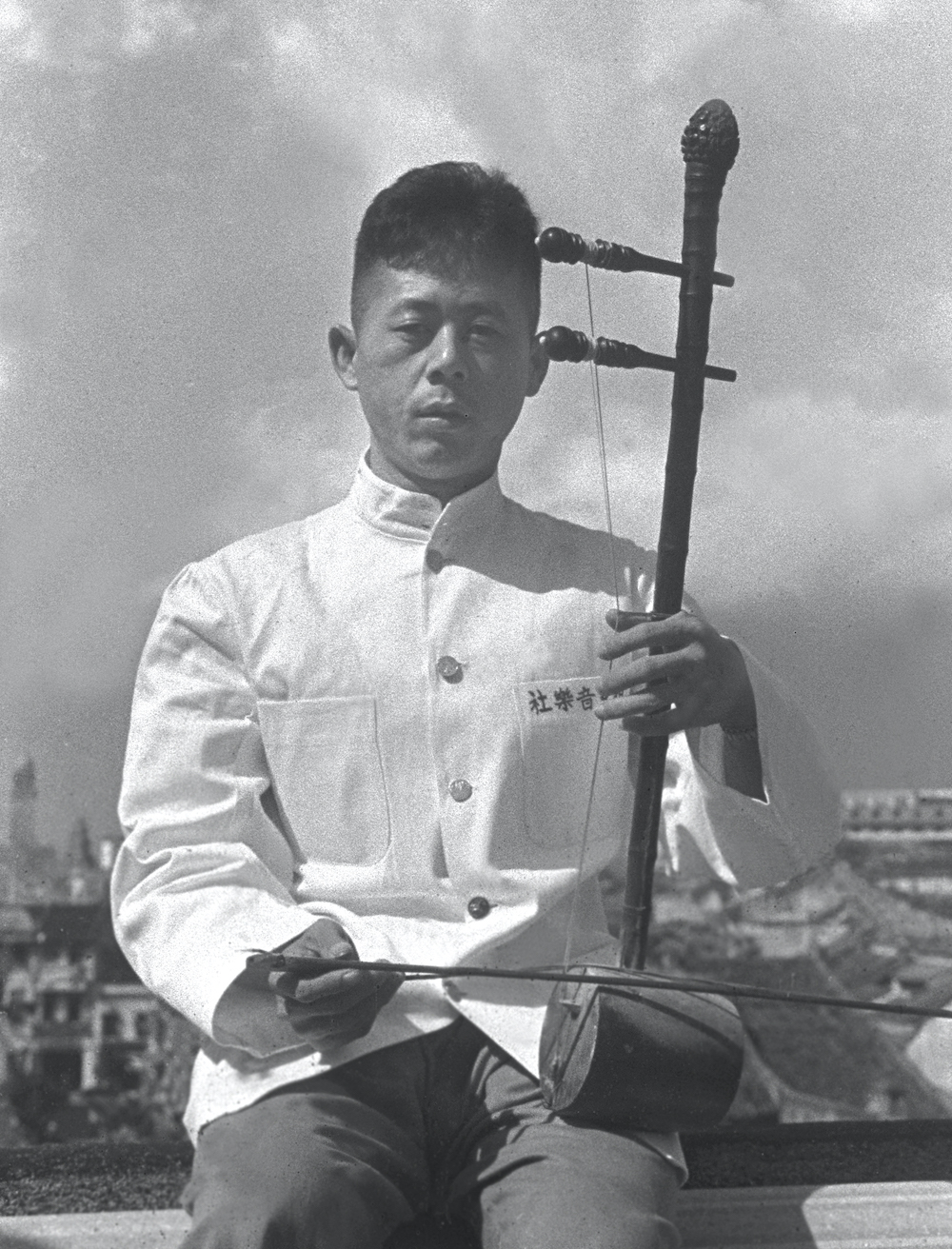

Nanyin, Music of the South

Nanyin, literally meaning “music of the south” in Mandarin, is a musical art form that is performed using vocals and a specific set of wind, string and percussion instruments. Its origin can be traced to Tang dynasty court music, as well as cultural traditions from the Song, Yuan and Ming periods. Nanyin flourished during the Ming and Qing periods in Fujian province, from where the art form was later brought to Singapore by Chinese immigrants in the 1800s.

Nanyin grew in popularity among Singapore’s early Chinese settlers as its familiar sounds served as an emotional link to their homeland. The cultural art form is usually played alongside Chinese opera performances, or during events such as temple festivals or private celebrations. Nanyin musicians also formed societies based on dialect or kinship, which enabled them to connect with kinsmen from the same hometown.

Today, nanyin is still performed in temples such as Thian Hock Keng, one of Singapore’s oldest Hokkien temples. In fact, Thian Hock Keng continues to uphold an age-old tradition of hosting nanyin performances in honour of the deity Guan Yin. The cultural art form is also practised by various musical groups such as Siong Leng Musical Association.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Courtesy of Quek Tiong Swee

Forms of Nanyin

Fujian Nanyin

The Fujian genre of nanyin uses the Hokkien dialect of Fujian province and instrumental music. It is transmitted through a long tradition of music that is expressed in three forms: instrumental suites; suites with instrumental and vocal parts; and ballads accompanied by an ensemble. Nanyin is integral to the cultural identity of Fujian province and is commonly described as the region’s “mother music” (muyue).

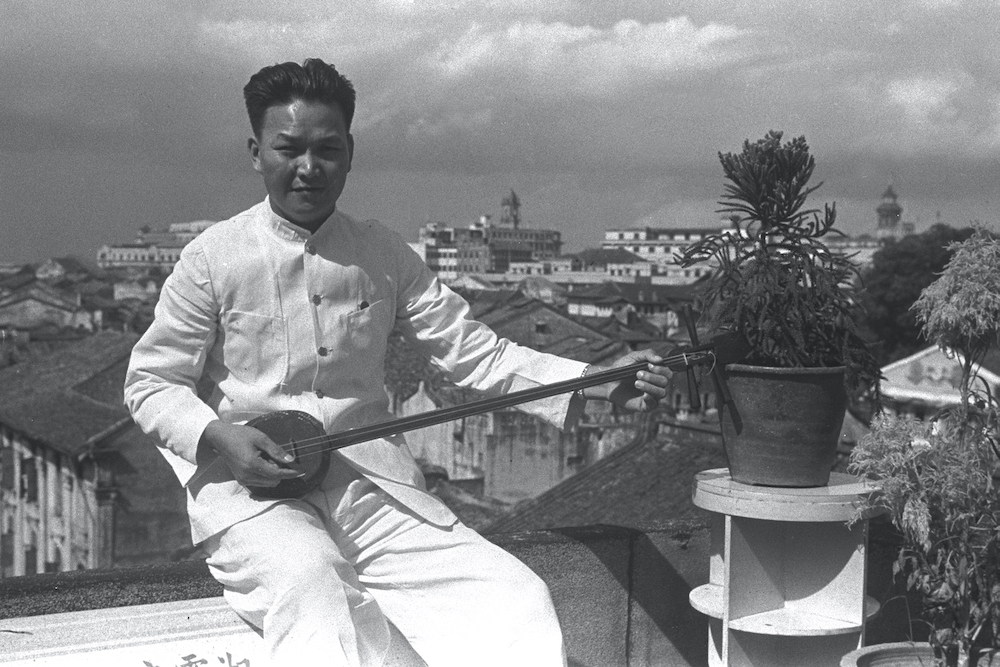

A nanyin performance is typically led by a solo vocalist who is accompanied by instruments such as pipa (four-stringed lute), dongxiao (bamboo flute), sanxian (three-stringed lute) and erxian (two-stringed bowed fiddle) as well as percussion instruments such as ban (wooden clappers to maintain rhythm). Traditionally, the pipa serves as the leading instrument and is used to provide the main melody.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Cantonese Naam-Yam

Cantonese nanyin, known as naam-yam in Cantonese, differs from Fujian nanyin in language, musical style, repertoire and instruments used. The genre of naam-yam comprises narrative singing where stories are vocalised through song. Naam-yam is usually performed using guzheng (Chinese zither), yehu (bowed lute made of coconut shell) or yangqin (hammered dulcimer), as well as ban. The lyrics of naam-yam are often melancholic and sombre, and revolve around the themes of heartbreak and struggle.

Naam-yam was once a popular form of entertainment among the Cantonese community in Kreta Ayer before the 1950s. Today, although naam-yam is rarely performed in its traditional form, some of its singing techniques have been adopted in Cantonese opera performances.

The musical instruments and score book on display were used by the Siong Leng Musical Association for their nanyin performances. Founded in 1941, Siong Leng is widely recognised for its contributions in promoting and preserving traditional nanyin music. Under former chairman Teng Mah Seng’s leadership, the association won third prize in the folk solo category at the 37th Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod.

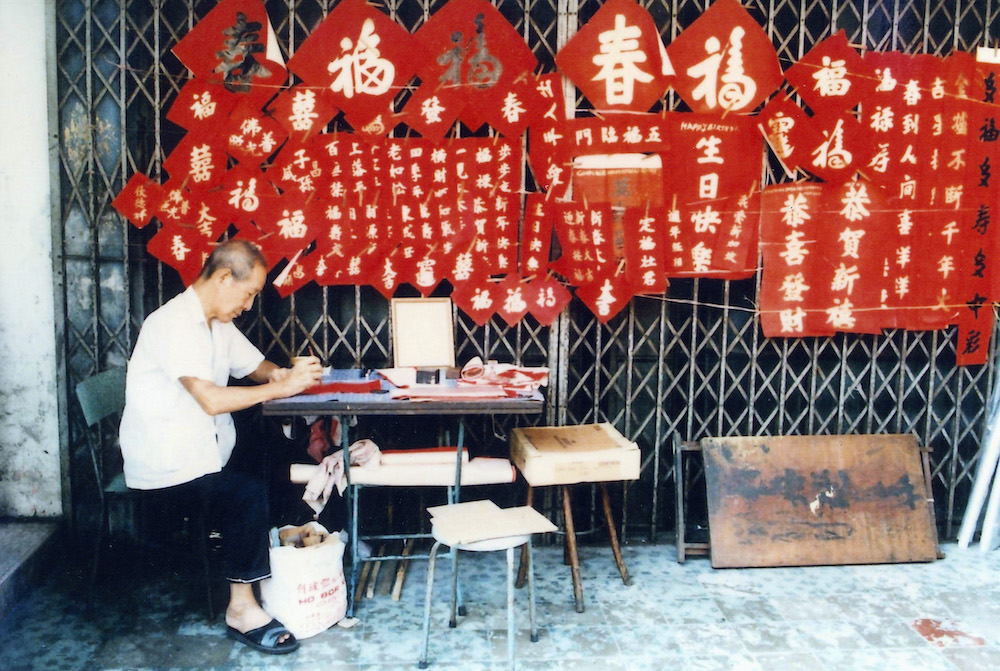

Chinese Calligraphy

Calligraphy was once an essential part of everyday life for the Chinese community as it served as the primary form of written communication. It was used in the writing of personal letters, advertisements, plaques and even road signs. Chinese calligraphy also serves as a means of expression and self-cultivation employed by poets, artists and intellectuals in their artistic and literary endeavours.

The tradition of Chinese calligraphy was brought to Singapore by Chinese immigrants. In the early 1900s, calligraphy was taught in Chinese-language schools such as Tuan Mong High School and Chung Cheng High School. In the 1900s, there was also a market for calligraphy signboards and such signboards can still be found hanging above the entrances of shops, temples and cultural associations in Chinatown.

Today, Chinese calligraphy is still appreciated for its timeless artistic and cultural values. While it is not as widely practiced as before, calligraphy is still taught in some schools as well as at community centres and cultural institutions. Calligraphy competitions, such as the annual National Calligraphy Hui Chun Competition, are organised regularly, and calligraphic paintings are also displayed in museums and exhibitions.

Courtesy of Quek Tiong Swee.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

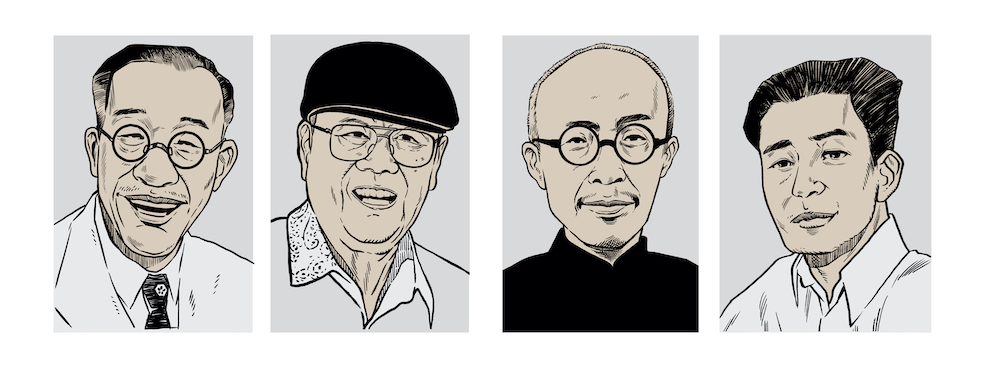

First Generation Calligraphers in Singapore

Tan Heng Fu (1870-1953)

Tan Heng Fu was a former Qing dynasty scholar who migrated to Singapore from Xinhui district in Guangdong, China when he was 62 years old. Tan was a skilled calligrapher and the artist behind the five Chinese characters on the façade of Majestic Theatre. The characters bear the building’s old place name of Tien Yien Dai Moh Toi, when it housed a Chinese opera theatre.

Wu Wei Ruo (1900-1980)

Wu Wei Ruo was a native of Dabu in Guangdong province who migrated to Singapore at age 13. Over time, he became highly sought after by local merchants who commissioned him to produce calligraphy for their signboards. These signboards can still be found outside Poh Seng Jewellers and Tiong Shian Coffee Shop along New Bridge Road.

Xu Yun Zhi, (1890-1960)

Xu Yun Zhi was a former teacher in his hometown in Kinmen County before coming to Singapore to work at Overseas Chinese Bank Corporation. He was one of the founders of Khoh Clan Association and served as Director of General Affairs at Kim Mui Hoey Kuan. Xu’s calligraphic works can be found on the building façades of Khoh Clan Association along Amoy Street and Chung Hwa Free Clinic at Telok Ayer Street.

Pan Shou, (1911–1999)

Pan Shou was born in Nan’an, Fujian Province, and migrated to Singapore in 1929 at the age of 19. Pan became the first calligrapher to be awarded the Cultural Medallion in 1987, and his calligraphy can be found on the façade of the Siong Leng Musical Association building along Bukit Pasoh Road. Pan wrote the five characters of the association’s name in 1992, as well as his name and the date of the inscription.

Traditional Chinese Teahouse and Tea Appreciation

In the early 20th century, traditional Chinese teahouses were important social spaces for the Chinese community where patrons could meet to mingle and be entertained. The patrons of these teahouses would drink tea and chat with friends while enjoying Chinese opera or nanyin performances at the same time.

Tea Appreciation

The origin of Chinese tea dates back to more than 3,000 years ago when the plant was used as a medicinal remedy in China. Due to its detoxifying and reinvigorating qualities, tea is widely consumed by people from all walks of life, and has become an integral part of Chinese culture, playing important roles in religious rituals, social customs and food heritage.

The act of brewing and drinking tea is regarded as a cultural art form. Tea brewers will match the selected tea with the right tea wares, infuse tea leaves in freshly boiled water, and pour tea into individual serving cups. There are different methods of brewing for different types of tea. For example, green tea is best brewed using a moderately high temperature while red tea will take a longer time to brew as its leaves are thicker.

Although tea has a long history, the import of tea into Singapore only started in 1819 when the British established Singapore as a trading post. During the period, local tea merchants imported tea from the Fujian province in China, and later from Taiwan from the late 1940s onwards. Due to strong local demand for tea, a number of tea firms were established in the 1920-30s, including Pek Sin Choon Tea Merchant, Guan Chong Bee Tea Merchant and the former Lim Kim Thye Tea Merchant.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Living Traditions

As Singapore transitions into the 21st century, new and alternative forms of entertainment such as digital games, movies and the internet have become popular. Consequently, cultural art forms such as Chinese opera and puppetry etc. are increasingly seen as leisure activities of the past. Nevertheless, devoted practitioners and stalwart supporters have continued to preserve and promote these cultural art forms to the younger generation.

In an effort to reach out to multicultural and younger audiences, some of these practitioners and performing troupes have introduced innovations into their cultural art forms by using different instruments, infusing other art forms, incorporating multi-media elements and even using English subtitles. Others have stepped up their outreach efforts to schools, community centres and museums in order to reach out to new audiences.

Courtesy of Nam Hwa Opera.

Courtesy of Siong Leng Musical Association.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Explore 3D Space