TL;DR

Originally a ramshackle cluster of sheds, Clyde Terrace Market was built in 1870 to house street vendor and hawker stalls amid criticism of the market’s unsanitary environment—a scathing editorial in the Straits Times dated 22 August 1871 called the market “a standing reproach to the Settlement... not only disgraceful in their outward appearance, but their internal condition anything but inviting. It is next to impossible to keep them clean”. This essay brings us through the history of the market, known colloquially as the “iron market”.

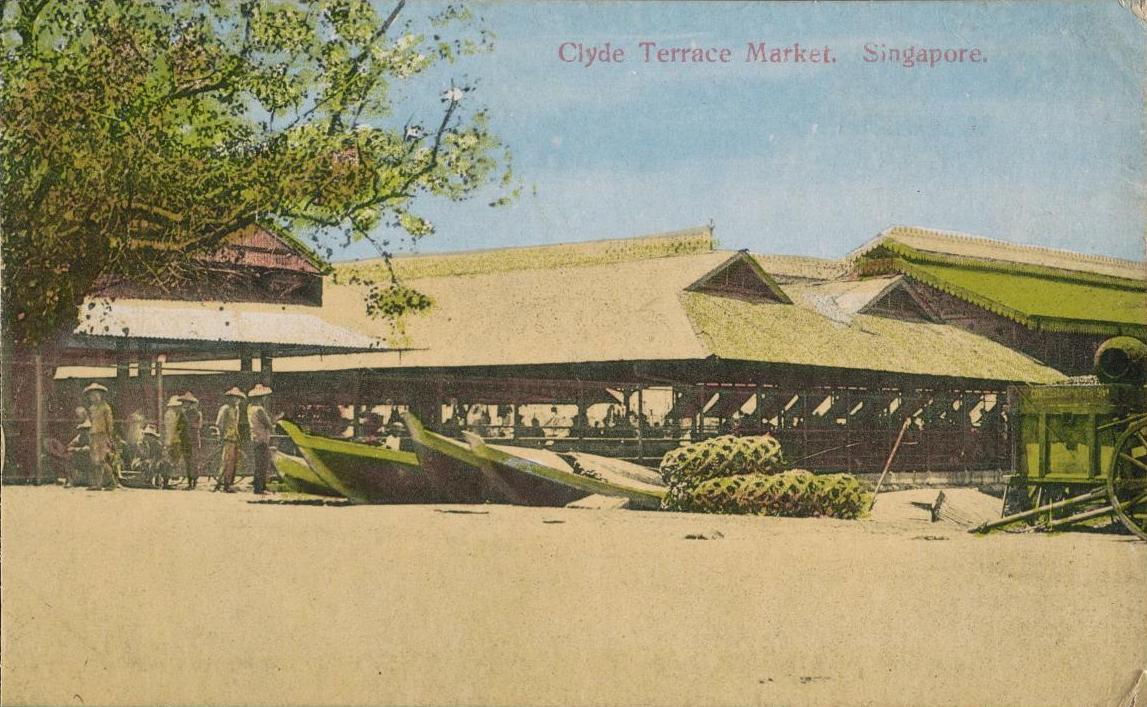

Image above: Clyde Terrace Market, early to mid-20th Century. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

A Necessity of the Neighbourhood

Within decades of Singapore’s founding as a British colony, a heterogenous settlement called Kampong Glam had formed around the Malay Royal Town designated by Stamford Raffles, Singapore’s first Resident and the colony’s earliest promulgator of urban planning. The settlement comprised Chinese, Malay, and Arab tradesmen and businessmen packed in an urban enclave containing narrow back-to-back residential and commercial shophouses. It became a densely populated area between Singapore River and Rochor River.

The considerable distance between the settlement and the nearest Telok Ayer and Ellenborough Markets in the city centre attracted street vendors and hawkers to congregate at the foreshore to provide a convenient location for residents to stock up on daily necessities. In the 1860s, an unregulated wholesale market sprung up on vacant government land along the reclaimed Kampong Glam foreshore, adjacent to a jetty where regional sellers unloaded goods.[1]

Newspaper articles from the late 1860s admonished the government’s oblivion to the unsightly market scene. Instead of punishing the vendors, an editorial urged the government to provide a proper market that was evidently a “necessity of that neighbourhood which should be kept in order and made a fit place for vending edibles.”[2] This provided the impetus for the Straits Settlement government to demolish the sheds put up by street peddlers and to develop a proper market.

View of Clyde Street Market and Boats at Seafront, Singapore. c.1872-1890. Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Plans to build Clyde Terrace Market were approved in 1872. It was named after the foreshore reclaimed in the early 1860s. In turn, its namesake was Colin Campbell, the Baron of Clyde and Commander-in-Chief of India from 1857 to 1860.[3] This echoes the origins of another municipal market, Ellenborough Market, its namesake being Edward Law, the Earl of Ellenborough, and Governor-General of India from 1842 to 1844.[4]

Who Designed Clyde Terrace Market

Up to 1875, the development of markets came under the purview of the Straits Settlements government, at which point their construction and maintenance were handled by the Office of the Superintendent of Public Works and Convicts and its successor, the Public Works Department helmed by the Colonial Engineer.[5]

Famed colonial architect G.D. Coleman was the first Superintendent of Public Works and Convicts. In that capacity, he took on the task of designing and building the colony’s first market structure, the Telok Ayer Market in 1834.[6] His successor, Captain Charles Faber too, was put in charge of building the following Ellenborough Market in 1843.

In the same vein, then-Straits Settlements’ Colonial Engineer, Colonel J.F.A McNair was listed as the new Clyde Terrace Market’s architect on its foundation stone.[7] However, the elegant filigree iron structure was more likely to be the work of the Municipal Engineer, Thomas Cargill who was put in charge of engineering works in Singapore. He was under the purview of Colonial Engineer McNair, who had oversight of the Public Works Departments operating in Singapore, Penang, and Malacca.[8]

Even though McNair was a competent civil engineer who had designed several public buildings such as government offices, as well as Singapore’s Government House and the General Hospital, his building designs were conformed to classical buildings typical of Royal Engineers’ works in colonies.[9] Designing the iron structure of Clyde Terrace Market was atypical of McNair’s engineering repertoire.

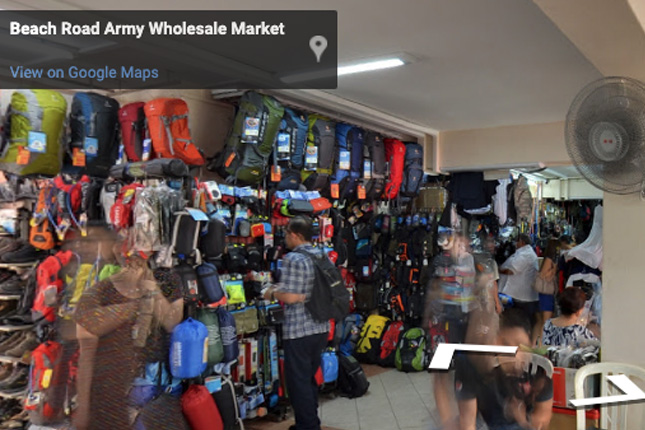

Conversely, Thomas Cargill was adept in using iron throughout a long and illustrious career as Singapore’s Municipal Engineer in the 1870s and 1880s. Cargill was best known for his iron bridge designs spanning Crawford Road, Arab Street and Coleman Street. He subsequently wrote about these projects and sent drawings to The Engineer, promoting a colonial outpost then to the forefront of British civil engineering development.

Cargill’s involvement in designing Clyde Terrace Market is evident after examining the cross diagonals girders on the roof trusses of Clyde Terrace Market, which resembled the trusses of Arab Street Bridge completed a decade later in 1883. The bridge trusses had double diagonal members formed from cast iron flat plates and rivetted together to form a “completely solid bracing throughout the whole bridge.”[10] A similar system of arched roof trusses was used to support Clyde Terrace Market’s pitched roof and to partition the enclosed interior into three aisles.

Page from The Engineer, 1883 showing drawings of Arab Street Bridge. Source: National Archives of Singapore.

Construction of the new Telok Ayer Market, c.1890. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.

An elegant filigree iron structure

Clyde Terrace Market was most likely produced in Britain after Cargill designed the structure and sent plans back to British foundries to manufacture. Flat, finished components ranging from bolts to beams would then be stacked tightly in cargo holds to prevent the relatively brittle cast iron components from shattering from impacts during stormy weathers. Arriving at the destination, these components could then be easily assembled under the supervision of an engineer who was able to read the assembly plan prepared by foundries. This process is remarkably similar to the instruction manuals that came with flat-packed furniture these days.

.ashx)

Iron Market, Singapore, c.1860-1899. Courtesy of National Archives (Great Britain).

This meant Cargill designed the market structure to be modular, with every component replaceable and each section extendable. Hence, it was no surprise that the initial shed-like structure was enlarged thrice to add a vegetable, fish, and chicken section as demand for fresh produce increased in tandem with the area’s urban population growth. At its peak, the market occupied two separate single-storey buildings.[11] The larger main building, containing two adjoining rectilinear sheds, accommodated 363 stalls uniformly arranged into meat, fish, vegetables, and edible sundry goods stalls. The poultry section, containing only 24 stalls, was in a smaller annex building located on Beach Road. The main building and annex were demolished in 1983 and 1970 respectively.

Beach Road Market and Police Station, 1963. Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Clyde Terrace Market appeared at a unique moment in Singapore’s architectural history, in which iron was increasingly associated not only with industrialisation, but with modernity itself. Beginning in the mid-19th century, iron became prominently featured in the construction of train stations, piers, bridges, warehouses, and other utilitarian structures. Engineers capitalised on iron’s superior tensile and compression properties to create long span, tall structures which could not be achieved with masonry and timber. These building types were not only essential for transporting people and goods across Britain and her colonies, but also supported the world’s insatiable demand for British manufactured products shipped worldwide.

Perception of iron in keeping markets clean

In Singapore, iron markets like Clyde Terrace Market were not only important municipal facilities but they also marked a key improvement in municipal governance, particularly in public health.

As a British colony, Singapore’s health policies followed those of British municipalities closely. In the absence of scientific understanding of how outbreaks occurred then, it was popularly believed that miasma, derived from the Greek word for “bad air” or “pollution,” was responsible for spreading diseases. This meant contiguous diseases back then, ranging from cholera to typhoid fever, were believed to be carried by invisible, vaporous substances thought to emanate from decaying matter and could linger on walls and other solid surfaces.[12]

Markets were at the forefront of preventing epidemics. These places were not only among the busiest places in the city; they were also essential for the well-being and collective health of the colony’s administrators, military personnel, and migrants.

Several articles from The Lancet, a leading medical and public health journal in Britain, during this period advocated the use of iron for hospitals, markets, abattoirs, and other building types perceived to carry miasma.[13] Iron’s strong compression, high tensile strength, and malleability create structural frames that enclosed large spaces and had the ability to create large openings on non-loadbearing walls. This introduced ample sunlight and promoted indoor ventilation which engineers believed was necessary to flush out miasma caused by decaying matter.[14]

The filigree iron structure of Clyde Terrace Market had minimal surfaces on which miasma could linger and was open on all sides to allow for the free passage of air and the admission of sunlight. Such a design, despite its simplicity and utility, epitomised good sanitary considerations of that period and represented one of Singapore’s early attempts to incorporate architectural considerations and deploy engineering advancements to address public health concerns.

The success of iron in ensuring good sanitation promoted its subsequent adoption in redeveloping other municipal markets such as Telok Ayer and Ellenborough Markets, completed in 1894 and 1899 respectively.

Conclusion

Clyde Terrace Market was a building of its time.

Its intricate and prominent iron structure, which stretched across a city block along Beach Road, gave rise to colloquial names such as thit pa-sat hau in Cantonese, referring to Beach Road facing the iron market, and Pasar Besi in Malay referring to its ironworks.[15]

Yet by the 1980s, the century-old market structure had become inadequate to meet the demands of the urban population shifting out of the city centre into suburban new towns. Instead of building sprawling, single-storey market structures, the housing authorities opted for many smaller, multi-storey buildings combining the market with cooked food hawker centre and sundry stores, each located within walking distance for a large catchment of new town residents.

Beach Road too was also undergoing drastic changes. The market had become out-of-place on a street undergoing high-density, high-rise redevelopment. Neighbouring Alhambra and Marlborough Cinemas gave way to Shaw Tower in early 1970s, while another longstanding public institution, the Singapore Volunteer Corps Headquarters vacated their site in 1984 after approximately 90 years of use.

View of Beach Road from Shaw Towers, 1976. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

It is perhaps befitting that the Gateway, itself an architectural marvel of its time, had taken over the market’s former site. The main structure for Clyde Terrace Market was demolished in the mid-1980s ushering the way for the twin trapezoid 37-storey towers with sharp converging angles completed in 1990.

Notes

- Savage, Victor R, and Brenda S. A Yeoh. Toponymics: A Study of Singapore Street Names (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2013), 328–329.

- “From the Daily Times, August 22nd. The Campong Glam Beach.” Straits Times Overland Journal, 26 August 1871, 3.

- Toffa Abdul Wahed, “Clyde Terrace Market,” Singapore Infopedia. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=5b0bac73-a0c1-4ee6-9e71-c10e228d6d90

- Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore…, vol. 2 (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902), 758. (Note: The Straits Settlements, which included Singapore, was under Indian Rule until 1867; some early street names and public buildings were named after Indian colonial administrators.)

- Colin Cheong and Wong Hooe Wai. Framework and Foundation: A History of the Public Works Department (Singapore: Public Works Department, 1992), 17.

- Lee, Kip Lin. Telok Ayer Market. (Singapore: Archives and Oral History Department, 1983).

- Freemasons. Eastern Archipelago. District Grand Lodge, Ceremony of Laying the Foundation Stone of the Clyde Terrace Market, at Singapore, the 29th day of March, 1873 (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1873), 12–13.

- Duncan Sutherland, “J.F.A. McNair.” Singapore Infopedia. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=2b22e5c6-ca35-4b4f-9725-96711800882d

- John Frederick Adolphus McNair. Prisoners their own warders: a record of the convict prison at Singapore in the Straits Settlements, established 1825 (Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co, 1899).

- “Arab Street Bridge, Singapore.” The Engineer, 9 Nov 1883, 358.

- Jane Perkins, Kampong Glam: Spirit of a Community (Singapore: Times Pub., 1984), 33.

- Michael Worby. Spreading Germs: Disease Theories and Medical Practice in Britain, 1865–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 112.

- “The Municipal Slaughter-house of Brussels.” The Lancet, 17 December 1892, 1049; Henry Tomkins, “Construction of Hospitals for Infectious Diseases.” The Lancet, 31 March 1888, 647.

- Travis R English, and Daniel Koenigshofer. “A History of the Changing Concepts on Health-care Ventilation.” ASHRAE Transactions 121(2), 45.

- Savage, Victor R, and Brenda S. A Yeoh. Toponymics: A Study of Singapore Street Names (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2013), 50.