TL;DR

Every ten years, Singapore's Henghwa community conducts a three-day Buddhist-Taoist ritual at Kiew Lee Tong Temple called the Decennial Universal Soul Salvation. Started in 1944 during the Japanese Occupation, this elaborate ceremony combines theatrical performance, religious rites, and traditional offerings to provide spiritual liberation for ancestral spirits and forgotten souls. The ritual features the sacred Mulian opera performance and concludes with a ceremonial burning of a paper boat to guide souls to their destined realms.

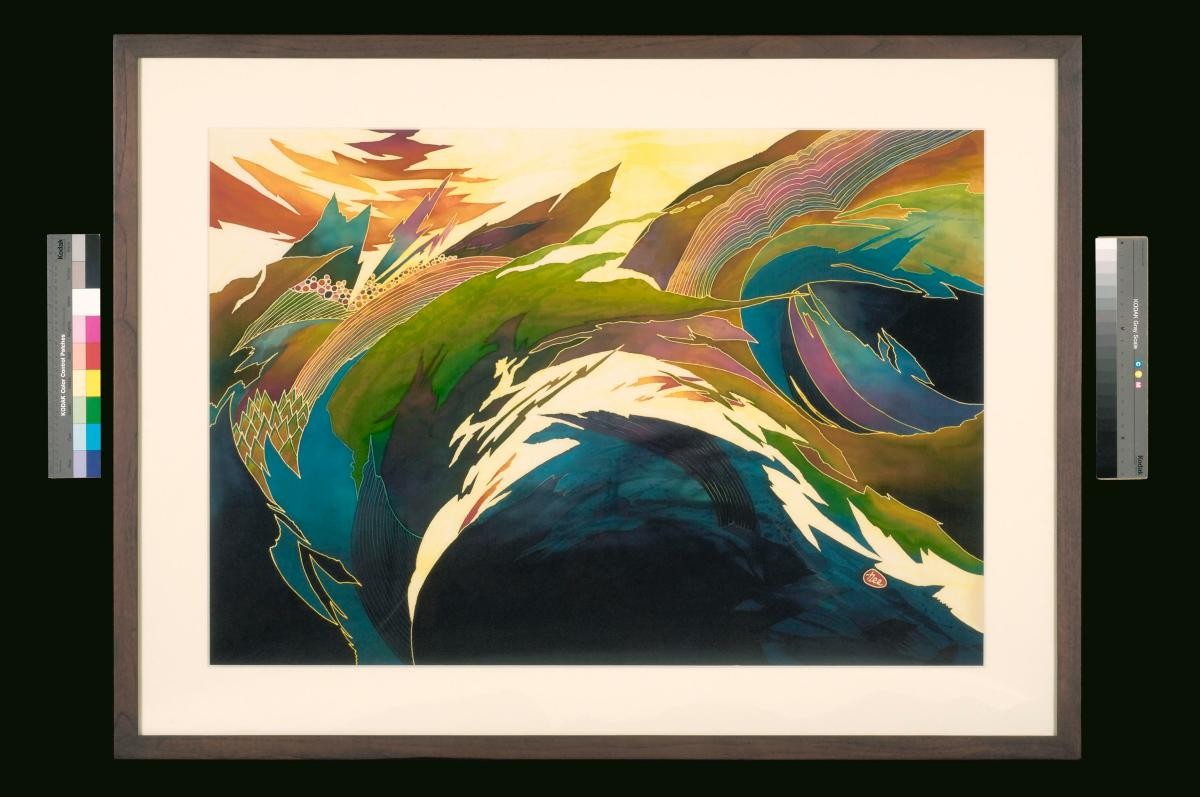

Top image: Fuji or planchette writing blessing the ritual stage. Image courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Once every ten years, the tranquil grounds of Kiew Lee Tong Temple in Singapore are transformed by the sacred ritual of the Decennial Universal Soul Salvation 逢甲大普渡—a rare, three-day ritual that bridges the human and spirit worlds. Deeply rooted in Buddhist and Taoist teachings and imbued with Henghwa 兴化 cultural memory, the ceremony offers spiritual liberation to both ancestral spirits and the forgotten souls who have no living descendants to honour them.

Held during the seventh lunar month as part of the Hungry Ghost Festival, this solemn event is a profound expression of compassion, communal duty, and ritual continuity. The practice traces its origins to the 1940s, during the Japanese Occupation, when the temple first conducted rites in response to the atrocities of the Sook Ching massacre. The inaugural ritual took place in 1944, intended to console the souls of the unjustly slain.

Over the decades, it has evolved into a major spiritual undertaking—one that continues to reflect the Henghwa community’s enduring values of remembrance, redemption, and collective care for the unseen.

Summoning the Invisible

Preparations for the ritual begin weeks in advance, informed by the sacred practice of fuji 扶乩 or planchette writing. The spirit of Immortal Chen Zhangzhe (持教善德陈长者) is invoked through the fuji practice to serve as the ritual's spiritual overseer. Under his guidance, the sacred grounds are ritually awakened, beginning with the solemn raising of the ritual banner li fan 立幡. Using ink mixed with consecrated cinnabar, the Immortal sanctifies the talismans and implements, purifying the ritual space and marking it as a threshold between the human and spirit worlds.

Outside the temple, a towering flagstaff—over 36 feet high—is erected. Adorned with a lantern, fluttering streamer, and a symbolic paper crane, it forms a luminous vertical axis that connects heaven, Earth, and the underworld. It stands as a spiritual beacon, signalling to unseen souls that they are being called forth and cared for.

Lantern-lit pathways, each shade topped with traditional bamboo yuli 雨笠 rain hats, guide the spirits of the six realms toward the temple. Within the grounds, paper effigies, children’s toys, and offerings fill the space, transforming it into a sanctuary for the neglected dead—those without descendants to remember them.

Among the most poignant elements are the gupan 孤盘 offerings—carefully arranged trays dedicated to forgotten souls. Each includes a handwoven pouch of rice and preserved radish (caipu/koli puay 菜脯), straw sandals (caoxie/cao-a 草鞋), and a bamboo rain hat (yuli/ho-li), all humble yet deeply symbolic gestures of care for the spirit’s journey. Added to these are comforting dishes, such as a thick, viscous soup believed to aid souls who struggle to consume solid food, and a soft starch paste intended to help those who died violently or in accidents “heal” from their suffering—restoring, in ritual form, what was once broken.

Theatre as Sacred Ritual

The centrepiece of the three-day observance is the ritual theatre performance of Mulian Jiu Mu 目连救母, or “Mulian Rescues His Mother.” This sacred drama tells the story of the filial monk Mulian (Fu Luobo 傅萝卜), who descends into the depths of hell to rescue his mother, condemned there for her misdeeds. Armed with divine tools bestowed by the Buddha and through acts of merit such as dāna (charitable giving), Mulian ultimately secures her release and rebirth into a more favourable realm.

At Kiew Lee Tong, this performance transcends the realm of conventional opera. It is not just storytelling but an embodied ritual. Every gesture is deliberate, every prop consecrated, and every performer ritually prepared. The performance unfolds as a sacred offering, sustained throughout by continuous prayers, liturgical chanting, and offerings to the spirits—carried out in tandem by both Taoist priests and Buddhist monks. Here, theatre becomes a living ritual, weaving together devotion, performance, and spiritual intercession.

A Dramatic Closure

At the ritual’s climax, the underworld deities Dua Di Ya Pek (大二爷伯; the Black and White Impermanence, also known in Chinese as Heibai Wuchang 黑白无常) make a powerful entrance, bursting through the temple gates and flanked by fearsome, elaborately costumed hell guards. This dramatic moment marks a decisive shift from turmoil in the spirit realm to the restoration of divine order. As the underworld officials gather the wandering souls, no spirit—no matter how forgotten or lost—is left behind. Their presence signals that the realm of the dead is being brought back into balance.

The ritual concludes with the solemn song ling 送灵, the sending-off of souls. At the heart of this final act is the burning of a large, ornately constructed paper boat, often inscribed with ancestral names and laden with symbolic offerings. This vessel serves as a spiritual conveyance, guiding the souls toward their destined realms in peace and dignity.

Preserving a Sacred Legacy

For the Henghwa community, the Decennial Universal Soul Salvation is far more than a memorial—it is an act of cultural preservation, spiritual healing, and communal affirmation. As ritual theatre and shared rite, it reinforces the profound interconnection between the living and the dead. In extending peace to unseen souls, the ritual becomes a testament to enduring values that the community holds dear: memory, compassion, and the human longing for transcendence.

This article is based on fieldwork conducted by Angela Sim.

Notes

[1] The six realms in Buddhist cosmology refer to the six states a being can be reborn into—God, Human, Demi-God, Animal, Hungry Ghost, Hell.