TL;DR

Today Singapore is a famously clean city with skyscrapers coexisting with greenery, where waste is well managed, water is recycled, and sustainability is a way of life. This article explores the journey of Singapore’s Green Plan 2030, the historic role of Karung Guni and the community’s involvement in creating a sustainable future.

Karung Guni is a Malay phrase for gunny sack, a now obscure English term that denotes a large hessian or burlap bag that held vegetables or coffee—usually discarded after use, that was repurposed by rag and bone men and scrap collectors to hold what they found until they could trade it for money. The bag was so identifiable to onlookers around the city that it became the term that defined the rag and bone or scrap collection profession. Karung Guni men and women have been a familiar sight to Singaporeans for over a hundred years, hauling the heavy sacks on their backs as they walked their rounds to collect discarded items, things they knew from experience still had value.

Ask any Singaporean to tell you about their memories of Karung Guni and the reply is always “the sound.” In his article “Karang Gunis: The Decline of Singapore’s Recyclable Collectors”,[1] Amirul refers to “the sound of Karang Guni”: “Karang Guni, toot, toot, toot”. You always heard a Karung Guni before you saw him because this was the way they announced their presence in the HDB block, and residents understood the noise as notice to prepare their newspapers, metal, clothes, and other items for his collection.

Growing up in Singapore, one of the authors has such memories herself. The familiar honk and echoing call of “Karung Guni” drifting between the blocks still “lingers in my mind. We would rush to the window and call out to him, and he would come up to our flat. We would be so excited and rush to the door with old newspapers and other items that have been stacked by the side inside the house. He would tie stacks of our newspapers, weigh them using his spring balance and give us a few dollars and take our old papers and books away. As a child, the excitement was giving him the items and collecting those few dollars. We were always fascinated by the man with his towering sack of recyclables. His visits were always around the same time, and he was part of our everyday routine.”

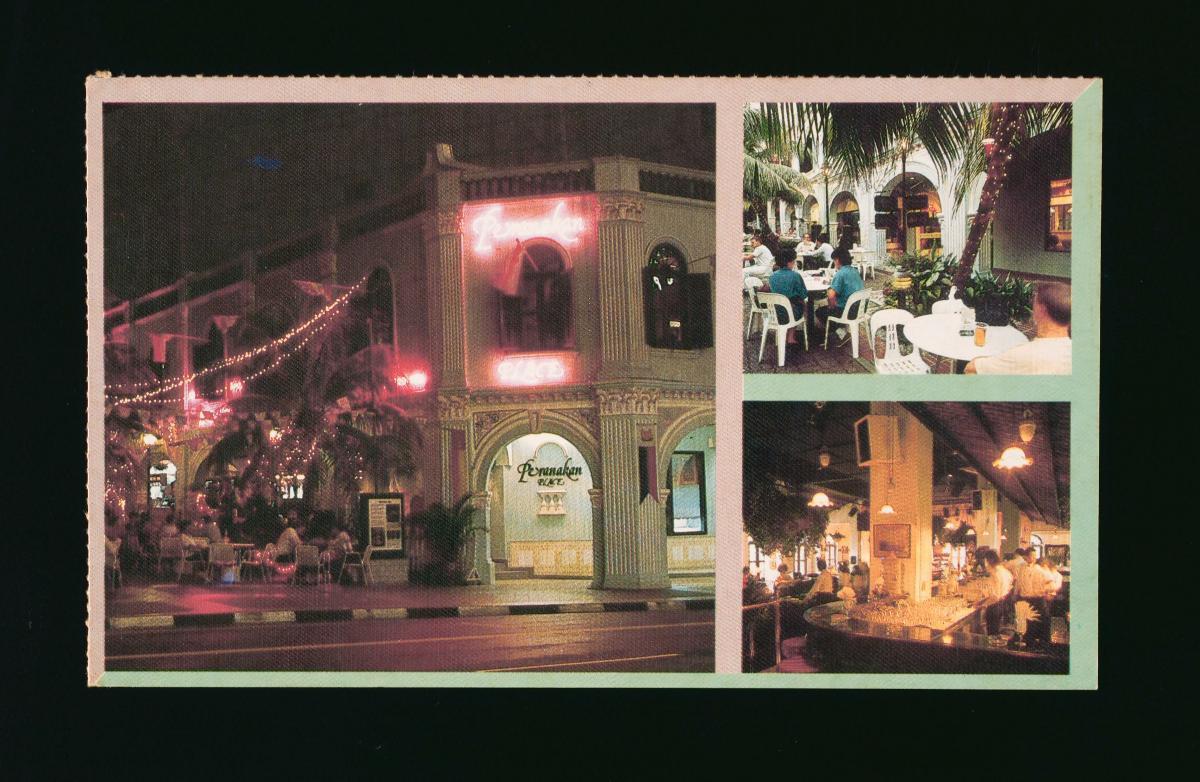

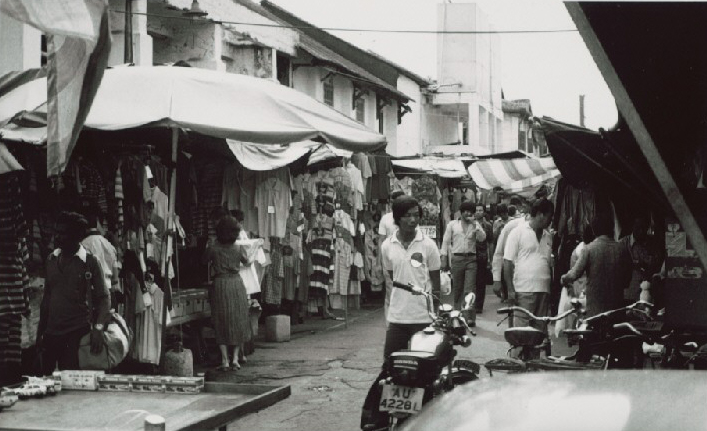

Integral to the exchange of unwanted products for money was the idea that used items had value. Even used newspapers were worth something, so every household would retain them to realise their value. The process was responsive, convenient and personal. Once the items had been collected—and a nominal price had been paid for them—the Karung Guni would then sort what they had collected and sell it on to the various resource recovery enterprises that existed on the island. For example, a broken household appliance could be repaired and resold or broken down into components that were then sold on to others who would in turn use these elements to repair other devices. Some components, fittings or elements were a commodity themselves, as the popularity of markets like Robinson Petang clearly demonstrate. Finally, when everything had been stripped of the resource—or there was nothing saleable left—then anything that remained went to landfill. The Karung Guni hence provided an invaluable door-to-door recycling service that bypassed the need for residents to sort waste or locate recycling facilities—a convenience that remains relevant today as Singapore still lacks comprehensive island-wide recycling bin coverage and widespread household waste sorting practices. Their personalised collection system effectively captured recyclable materials that might otherwise end up in general waste, demonstrating how human-scale solutions can complement formal recycling infrastructure.

Modern Practices

Today, the Karang Guni men and women still exist, although the activity has evolved with time. Some contemporary collectors use trucks and advertise on digital platforms to reach more households and streamline their operations. Organised opportunities to sell their wares exist as well. The Market Gaia Guni at Woodlands Industrial Park houses 15 stalls and is open on weekends and public holidays as vendors collect used items including clothes, electronics, and antiques on weekdays and resell them when the market is open on the weekends. Despite having a good system in place to resell what they can, the vendors report their "overall profits are meagre”.[2]

With Robinson Petang and the Thieves Market no longer trading, Sungei Road remains a fixture for the reuse trade with what is known today as the Sungei Road Green Hub, where the shops offer a varied selection of secondhand ware such as clocks, sculptures, bicycle helmets and other items. These vendors claim that the shrinking interest in buying used or second-hand items among Singaporeans remains a challenge. The new generation of Karung Gunis, such as Mr Bryan Peh, uses Instagram and Facebook to build awareness on scrap trading and to woo new customers as he wanted to save his father’s Karung Guni business. Mr Peh hopes to revitalise the “fortunes of Karung Gunis in Singapore” as he feels there is “uniqueness” in this and that it can “benefit the environment”.[3]

Mr Peh is not alone. Mr Daniel Wong left his comfortable office to start a company in 2016 to provide on-demand recycling by collecting unwanted items. He then either sells the items to new owners or recycling plants.[4] But such stories are uncommon, and interest in practice is dwindling.

Waste management in Singapore

The National Environmental Agency (NEA) reported that approximately 5.88 million tonnes of solid waste was generated by Singapore in 2020. Paper and cardboard were disposed of the most and made up 20 per cent of the total waste generated, followed by ferrous metal and plastics.[5] To minimise waste and increase recycling, the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) play a crucial role by preventing waste generation at its source and bring along numerous benefits including diversion from landfill.[6]

But despite the significant education and outreach on this issue, the landfill site is filling faster than ever. Perhaps learning from the Karung Guni’s work could assist in alleviating that burden? Singapore’s HDBs and vertical scale make recycling difficult and enormous amounts accumulate quickly, requiring regular clearance. Karung Guni and their rounds—and a return to the idea of every item having some intrinsic worth as a resource—may be one way the city can address the issue.

Notes

- Amirul. “Karang Gunis: The Decline of Singapore’s Recyclable Collectors”. Medium, 2020.

- “Karung guni men struggle with low profits, dwindle in numbers as Singaporeans purchase fewer used items”. Channelnewsasia, 26 Jan 2023.

- Ibid.

- “Credit trader turned karung guni man has no regrets”. The New Paper, 1 Aug 2016.

- “Waste Management”. SG101, www.sg101.gov.sg/infrastructure/case-studies/wm/.

- “Waste Minimisation and Recycling”. National Environment Agency, www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/waste-management/3r-programmes-and-resources/waste-minimisation-and-recycling.