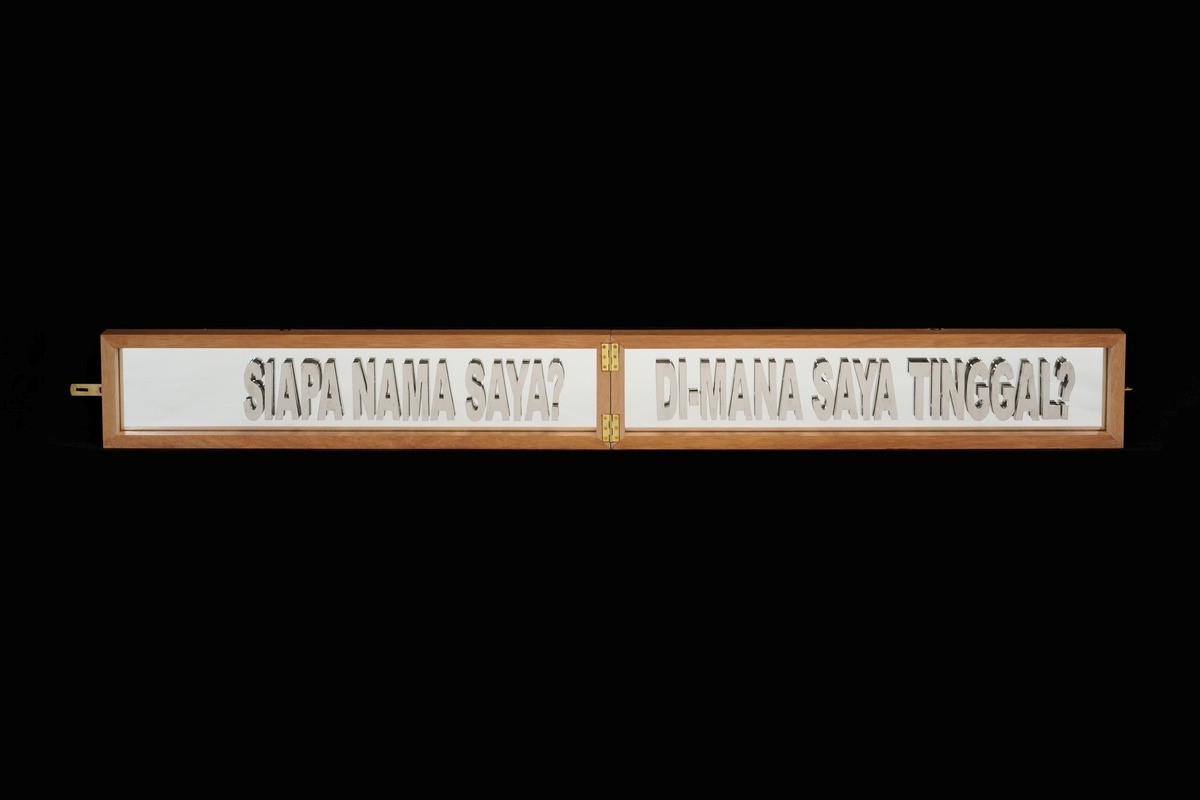

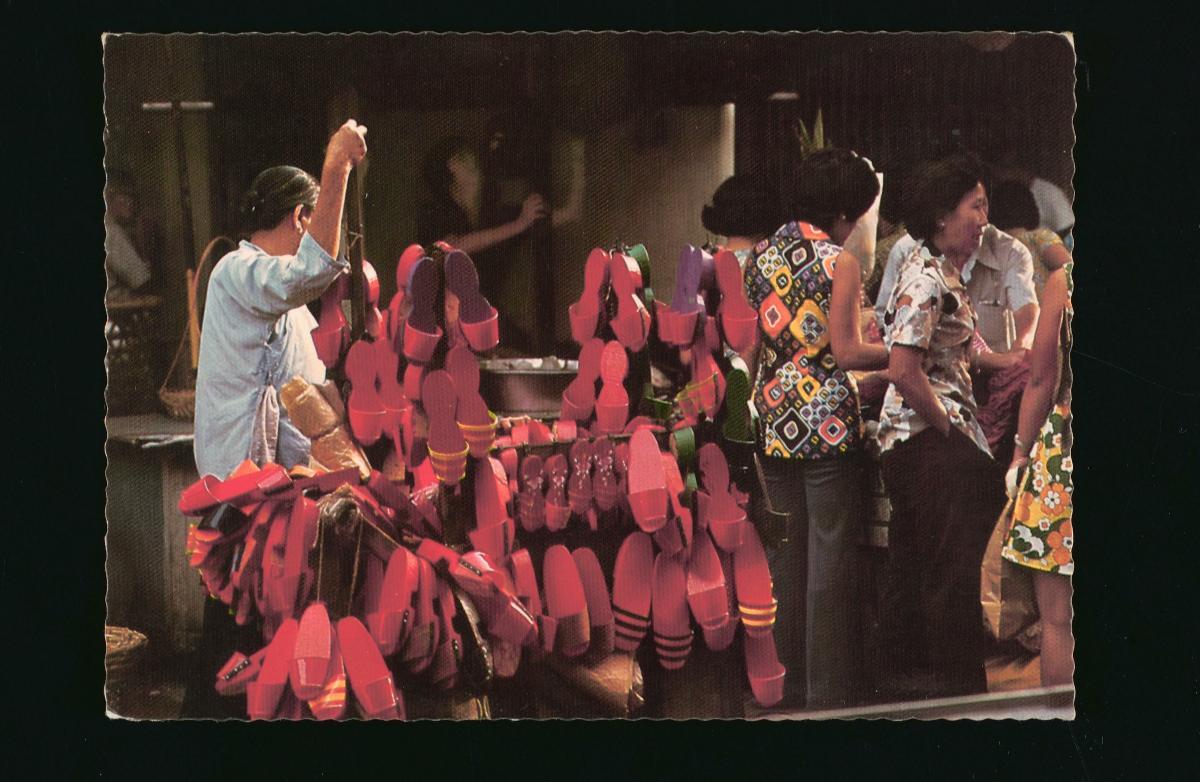

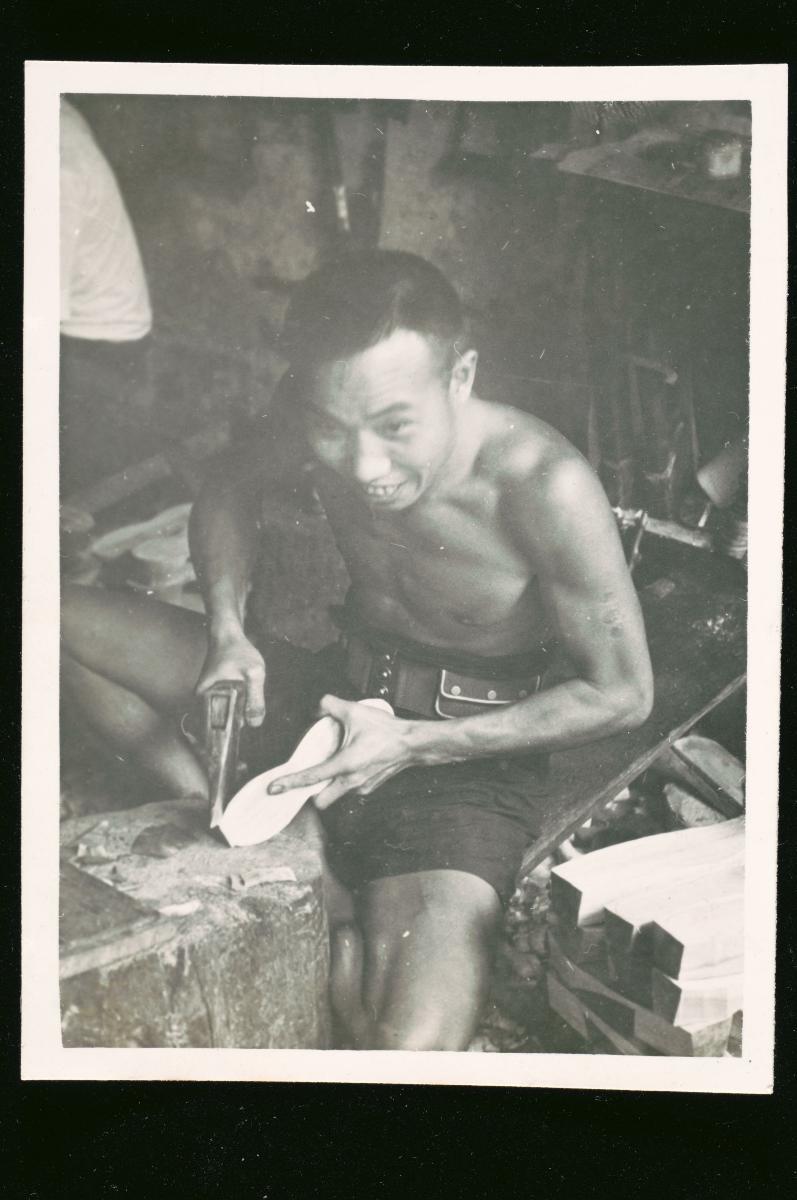

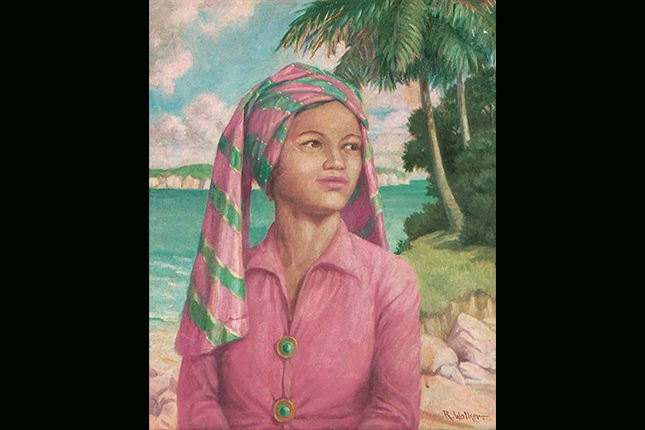

Cheo Chai-Hiang is one of Singapore’s most significant artists of the second generation. His career trajectory differs quite starkly from those of his contemporaries: while artist like Anthony Poon, Thomas Yeo and Eng Tow were espousing new forms of abstraction, and Tang Da Wu is today remembered, of course, for founding The Artist’s Village in Sembawang in the late 1980s, Singapore’s most significant avant-garde artists’ collective, Cheo was making a name for himself outside of the country, and – even more importantly – for embracing conceptualism. He is chiefly known today for 5’ x 5’ (Singapore River), a proposed work that consisted of little but a hand-drawn square, measuring 5 feet by 5 feet, rendered over the space of a wall and the adjoining floor. It is held up today as one of the first work of conceptual art by a local artist. Both works considered here, What is My Name? and Three Long and Two Short Clogs, are from Cheo’s recent show, IN A COWBOY TOWN..... 人在江湖..... As he notes: “人在江湖... is not the Chinese translation of In A Cowboy Town...Both 人在江湖... and In A Cowboy Town.. depict a state of lawlessness and anarchy that can permeate the structures of an individual’s state of mind, or circumstances; or the state of affairs in a work place, an organization, a society or the zeitgeist of the times we live in. The use of the two phrases in the title of the exhibition conjure up images that are incommensurable with one another. The character 江湖 literally translates as rivers and lakes and refers to “the social world inhabited by sects, clans, disciplines and various schools of the martial arts, as well as nobles, thieves, beggars, priests, gangsters, merchants and craftsmen”. ……Both In A Cowboy Town... and 人在江湖... are the first lines of two incomplete idiomatic phrases. This incompleteness opens a space for the viewer’s own speculation and reflection on “the state of things.” (From the exhibition catalogue.) The last claim is perhaps the most emblematic of Cheo’s practice. His objects – like the hand-drawn square of 5’ x 5’, a work that seemed to be “about nothing” (in the words of esteemed art historian T.K. Sabapathy) – are enigmatic, evasive, self-contained. They require much of the viewer, in terms of bringing their own ideas, readings and experiences to the understanding of these strange entities. What is My Name? is perhaps the more explicit of the two in terms of its references: the questions it proffers the viewer, “Siapa nama saya?” and “Di-mana saya tinggal? (“What is my name?” and “Where do I Live”) refer, of course, to the lines contained in Chua Mia Tee’s National Language Class, one of Singapore’s most famous works of art to emerge from the Social Realist movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. In that iconic painting, students in a Malay language class – the national language, as it was then – pondering the questions, “What is your name?” and “Where do you live”? Cheo, in reimagining these questions in the first person, some six and a half decades after the original, and five decades into independence for Singapore, foregrounds instead the reflexivity that accompanies the Singaporean identity at a moment of great transition for the country: ballooning immigration numbers, among other structural and social shifts, have caused much soul-searching and – indeed – public discontent among the citizenry. Three Long and Two Short Clogs is perhaps less immediate, in its significance: the work is one of a series that utilizes that almost vanished phenomenon of everyday life hereabouts – the humble clog, once the province of elderly ladies, now replaced by the near ubiquitous flip-flop. Cheo worked with a clog maker in Malacca – where he is based these days – to produce these clog works, as a means of engaging with what he perceives to be a dying trade. The specific form of these clogs here also reference the Chinese saying “三长两短” (“three long and two short”), which is an idiomatic expression to indicate matters of an untoward nature, e.g. death, disease. The piece not only reflects Cheo’s interest in issues of vanished and dying histories, but also his love for linguistic play, a fact that has remained quite constant in his visual vocabulary.