At the tip of the Malayan Peninsula, close to the equator, there sits a landscape of generous greenery, hills and valleys between Malaysia and Indonesia. Trees provide shade, and tropical rainforest climate brings high humidity and abundant rain, without any distinct seasons.

This island has had many names over the years.

Why Temasek?

No one can say for certain what the origins of the name are, despite its regular appearances in early Malay and Javanese texts. However, it has been conjectured that it comes from the Malay word tasik, meaning “lake” or “sea”, and in this case, probably “place surrounded by the sea” or “Sea Town”.

Even its spelling has taken on many forms; Tumasik in an old Javanese poem in 1365, Chiamassie in a version of Marco Polo’s travel account, and Danmaxi as it was referred as by Chinese trader Wang Dayuan.

During the 14th-century, Singapore was also known as Singapura in the Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals - meaning “Lion City” in Sanskrit. Tan Sri Buana (also known as Sang Nila Utama) was the man who named the island city as such after a visit in 1299, during which he sighted a “lion”. However, the events are still a subject of debate today: was Sang Nila Utama a true Srivijayan prince from Palembang, as recorded in the Malay Annals, or was he a mere mythical figure?

Historical Artefacts

A set of Javanese-style jewellery, believed to be from the era of the East Java-based kingdom of Majapahit, which encompassed much of Southeast Asia at its peak in the 14th century, was discovered by a group of Chinese workers at Fort Canning Hill in 1928. This discovery was described in the newspapers as one of British Malaya’s most interesting archeological finds. It serves as an indicator of the Majapahit’s existence and a reminder that in the 14th century, the island of Singapore was under the political and cultural ambit of the Majapahit Empire before the British arrived in 1819.

Other 14th century artefacts, such as shell remains, animal bones, Chinese coins and ceramics were found after an excavation at Empress Place in 1998 led by Professor John Miksic, providing further physical evidence of material culture from an earlier time. The major find from that excavation was a Javanese-style figurine of a rider on a horse. Made of lead, it is the only statue of its kind that has been discovered in Singapore. Unfortunately, the head of the rider was never found, which gave the statue its “Headless Horseman” name.

There were various shards of Chinese ceramics, including Longquan Celadons, and Song Dynasty Chinese coins. There was also a figurine of a rider on a horse that bears hallmarks of Javanese art from the 14th-century Majapahit Empire and offers evidence of strong trade and cultural links between Java and ancient Singapura.

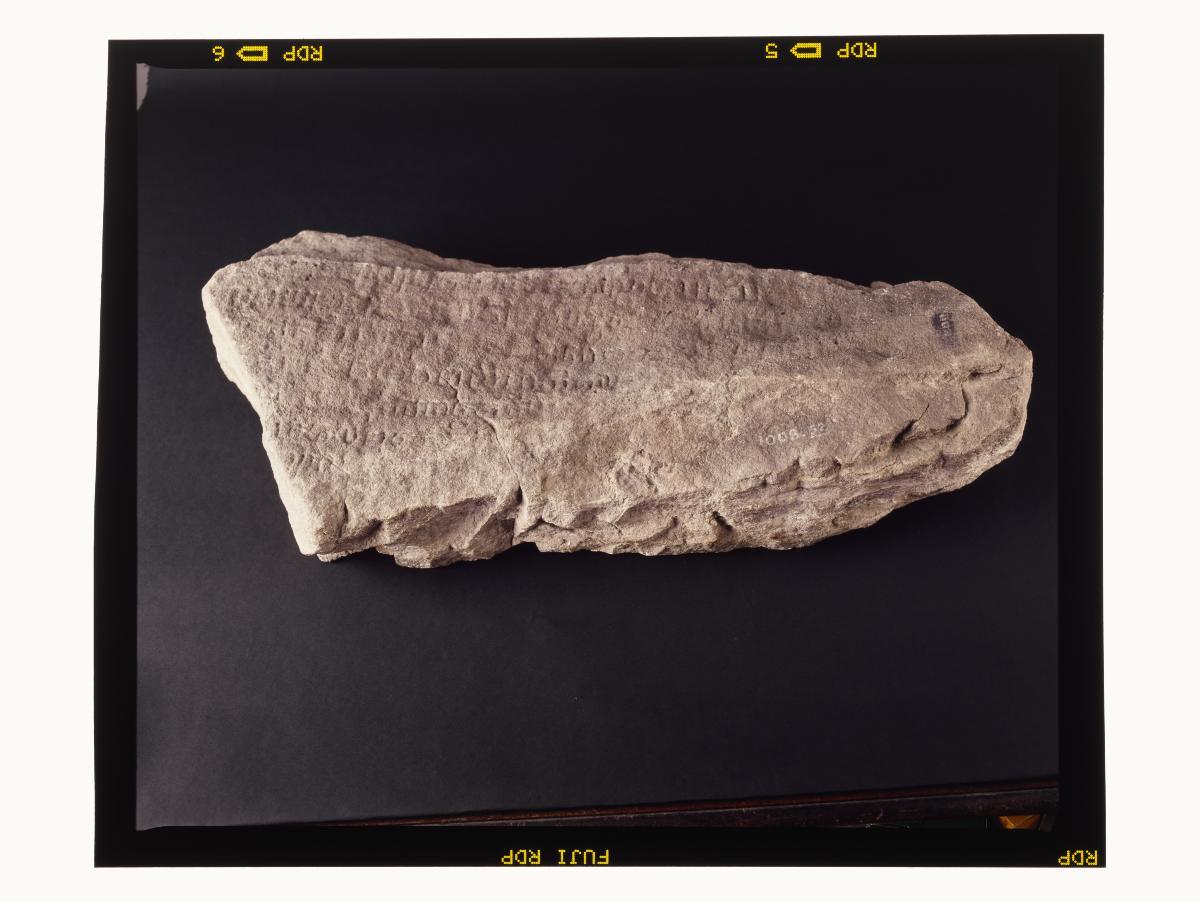

The Singapore Stone

The area surrounding the river was framed with large rocks, with the Singapore Stone sitting at its mouth – the Rocky Point. It was said to have been hurled there by the legendary Badang, the strongest man in Temasek at that time. Believed to be the oldest record of writing found in Singapore, the stone has inscriptions in the Kawi script and some Sanskrit words, and has been dated to between the 10th and 14th centuries.

All that is left of the stone now is a small fragment with ancient inscriptions that cannot be deciphered. The arrival of the British resulted in the loss of many traces of Ancient Singapura, and the Singapore Stone was eventually blown up in 1843 for the British fort and quarters.

Related Content

The River of Time

Beyond myths and legends, the Singapore River holds clues and artefacts that can shed light on our rich history. These discoveries help to paint a more complete picture of Singapore’s distant past.

Being naturally sheltered by the Southern Islands, the mouth of the Singapore River was the old Port of Singapore. As Singapore lies at the confluence of seasonal winds and monsoons which ships relied on for travel, the river became the centre of trade and commerce.

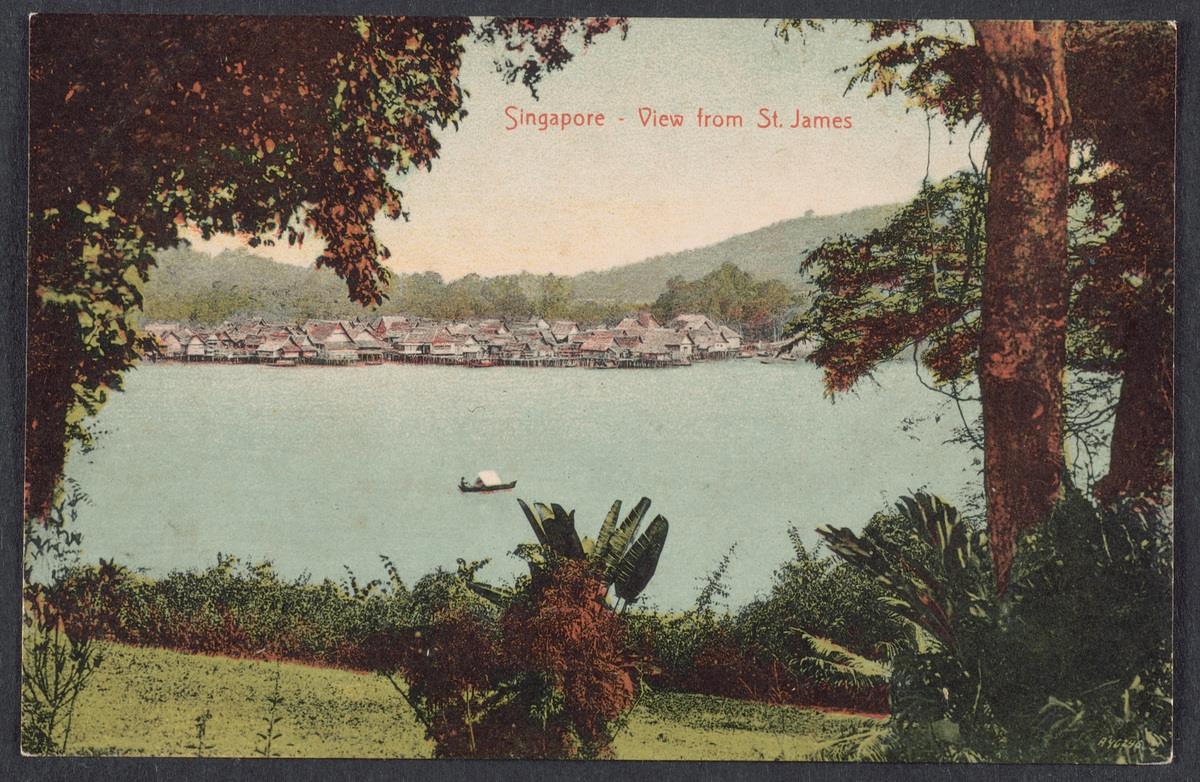

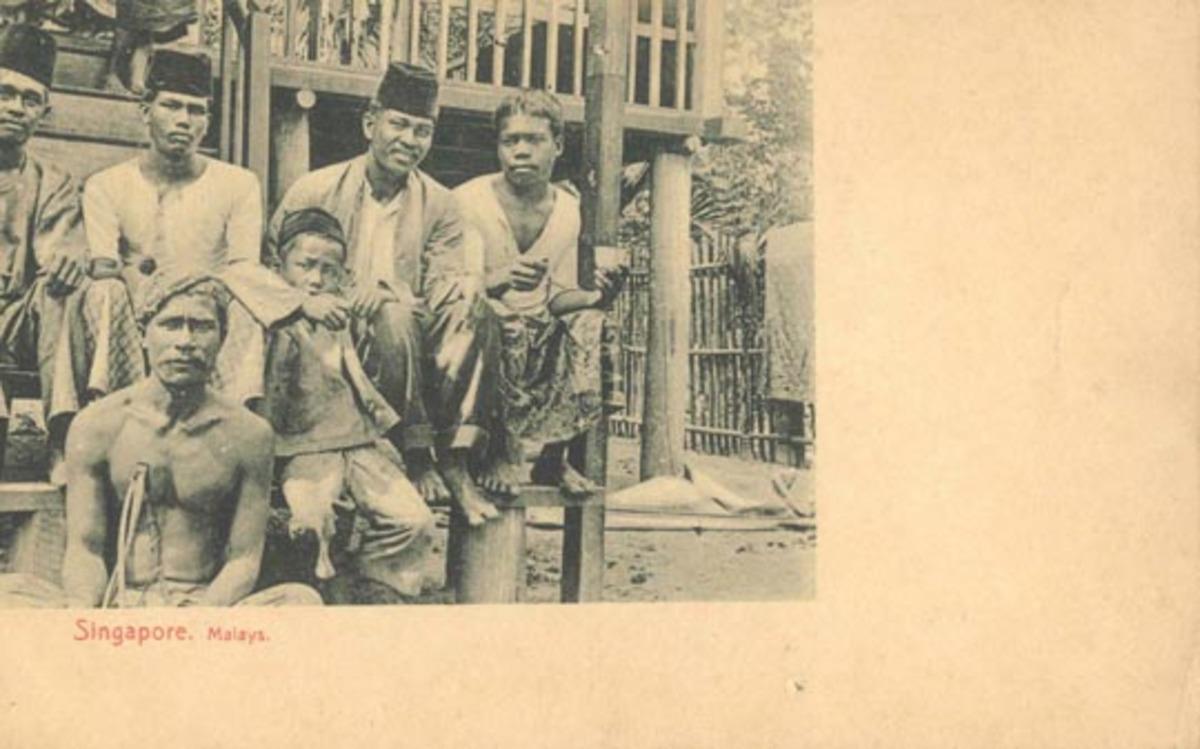

The river was constantly bustling with activity. The Orang Laut, “sea people” in Malay, were the earliest known inhabitants around the river, living in sampans at its mouth, and in a village called Kampong Temenggong, located at the north bank of the river, along with other Malays.

With locations such as the Raffles Landing Site, a swimming spot for children at high tide, and where bridges provide connections between people and places then and now, the Singapore River is a symbol of the past and present coexisting side by side.