TL;DR

The laborious work of conservation is often invisible to museum visitors, despite it being so central to the preservation of our national heritage. MUSE SG delves into the conservation process behind two 19th-century boundary markers.

MUSE SG Volume 15 Issue 02 - July 2022

Read the full

MUSE SG Vol. 15 Issue 2

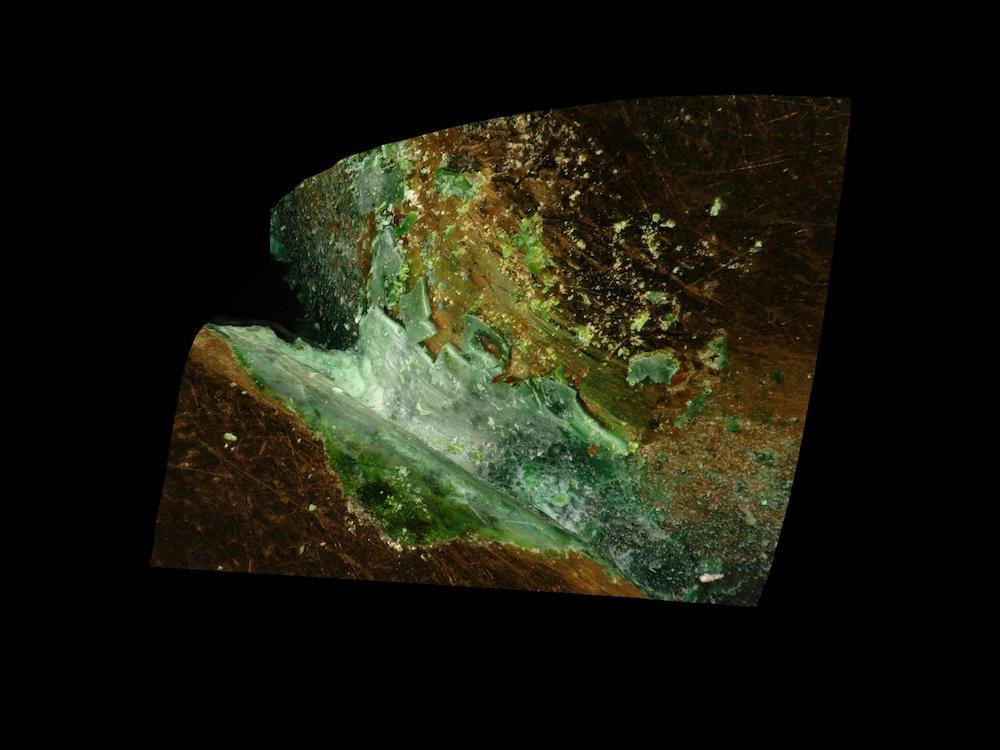

Image Above: Conservator Berta Mañas Alcaide (left) and Sharon Lim, a colleague from the Heritage Research and Assessment department, conducting an initial visual assessment of the boundary markers upon their arrival at the Heritage Conservation Centre.

A key part of the museum experience is encountering stories told through historical objects. We stand before an artefact, admiring its form and the layers of meaning it holds. We imagine it existing during the time of its creation — which could be as far back as a millennium ago. After all this time past, perhaps buried beneath the earth or underwater, perhaps in a collector’s home, it finally finds a permanent abode in the museum, where it is given a new lease of life.

But usually invisible to the visitor’s gaze is the laborious conservation work carried out before the object makes its way to being encased in the vitrine. How did an artefact look when it was first discovered and what was the conservation process like before it was housed in the museum, where we now view it in its preserved form?

We trace the conservation journey of two 19th-century artefacts — merchants Sim Liang Whang’s Teck Kee and Tan Kim Seng’s Hong Hin boundary markers — and examine the complexity of the behind-the-scenes work. Discovered in 2021, the condition in which the markers were found is vastly different from what they are today, thanks to the work of Berta Mañas Alcaide, Senior Conservator (Objects), Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC), who specialises in stone conservation.

The Markers’ Original State

Boundary markers were installed in Singapore from 1881 onwards to delineate the boundaries of privately owned land. Both the Teck Kee and Hong Hin boundary markers, made of granite from a local quarry, were discovered near each other in the Ulu Pandan area of Dover Forest. Two-thirds of the Hong Hin marker had been buried vertically with the remaining portion exposed, while the Teck Kee marker was completely underground. After a careful excavation, they were sent to HCC for assessment, analysis and treatment.

The first thing that a conservator does upon receiving a new artefact is to assess its condition. Mañas notes:

“The boundary markers arrived at HCC covered with mud and in a very wet condition. The exposed part of the [Hong Hin] marker had biological matter; these may include plant, algae, moss and lichen. Anything that enters HCC with biological growth or pests would have to be treated first to prevent contamination.”

Mañas applied ethanol to eliminate all biological matter on the markers, and mud was removed with deionised water and soft brushes. This process of cleaning had to be done meticulously as there were areas of engravings on the stone with paint remains; it was imperative that the paint would not be accidentally removed during the cleaning procedure. Hence, for the carvings, she cleared the mud slowly and carefully using cotton swabs.

After cleaning the outermost layer of the markers, granite particles were observed to be missing on the surface as a result of erosion due to environmental conditions. At the same time, carvings on the stones became more apparent. The Hong Hin marker is one of the few known boundary markers carved with both Chinese and English characters: ‘豊興山’ (Hong Hin’s Estate; ‘Hong Hin’ was the name of the business owned by eminent merchant Tan Kim Seng); and ‘T.K.S.’, Tan’s initials, below the Chinese characters. The Teck Kee marker, on the other hand, had only ‘德記界’ (Teck Kee’s Boundary) engraved on it. Chop Teck Kee was a business owned by Sim Liang Whang. The two boundary markers are the only ones associated with the two pioneer businessmen that have been found.

Some black paint was also observed on the exposed section of the Hong Hin marker over the Chinese characters, as well as on the Teck Kee marker. On closer inspection, Mañas discovered red paint fragments—which proved to be the original colour of the carvings— some of which were beneath the black paint. Red paint was only found on the Chinese characters for both markers, not the English initials for the Hong Hin marker. As a result of natural degradation, remains of the original red paint were minimal, in poor condition and fragile.

The Question of ‘Originality’

Following the discovery of the red paint, conservators discussed with museum curators whether to retain the black paint, or to remove it and thus reinstate it to its ‘original’ state. The removal process would be irreversible.

Although parts of the red paint had been painted over with black, the state in which the stones were discovered also constitutes a part of their history. Is there ever an ‘original’ state for a historical artefact that has undergone manmade and natural changes over a long period of time? This is a perennial issue faced by conservators: which ‘version’ of the object to treat for preservation.

The conservators and curators jointly assessed the Teck Kee marker and its contextual history, as well as the different possibilities of conservation treatment. Weighing the erasure of a part of the object’s history against the importance of that particular feature to the artefact’s biographical history, the team’s eventual recommendation was to remove the black paint as it was not considered original. Furthermore, it would be ‘visually disturbing’, as retaining the black paint would affect the legibility of the Chinese characters.

Mañas proceeded to remove the black paint for the Teck Kee marker, though this proved to be less than a straightforward task as some of the red paint sat underneath the black paint. To effectively remove only the black pigments while retaining the red ones required many mechanical and chemical trials. After testing different types of solvents, the black pigments were removed successfully, and photographic evidence of the stone with the black paint was archived for future reference.

Mañas’s next step was to consolidate the fragile red pigments. She applied a consolidant to ‘glue’ the remains of the red paint to the stone so that they would not chip off. Similarly, this process is irreversible — once applied, the consolidant cannot be removed without compromising the red paint.

Another consideration during conservation is whether to restore certain original features if some of them are lost due to degradation. Mañas explains the principle of restoration in conservation:

“Generally, conservation does not involve repainting what is missing. However, if, say, 95 percent of the paint is still intact, conservators may carry out colour retouching—that is, to apply colour at the missing areas—albeit using a material that is different from the original. But during this process of colour retouching, it is crucial to never alter the original paint, and this is a principle that is common across the restoration of paintings and objects.”

In the case of the Teck Kee marker where more than 95 percent of the original red paint was lost, Mañas did not perform colour retouching, thus leaving only fragments of the original red paint. Still visible to the naked eye, however, these fragments allow viewers to imagine what the boundary marker might have looked like back in the day with its bright-red engraved characters.

Permanent Home in the Museum

After conservation, the artefact is ready for its debut to the public with its refreshed look—now safely nestled in its permanent home, the museum, as part of the National Collection. An object of cultural importance, it will be preserved for time immemorial for future generations. Due to the material vulnerability of these historical objects, however, there are several considerations as to how they ought to be displayed in the museum for optimal preservation. These include environmental factors such as the humidity level and lighting, as well as the method of mounting and whether or not to encase the artefact.

For the Teck Kee marker, which is currently on display at the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall1, Mañas and the curators decided it was best to display it vertically and to have lighting angled from the side for better legibility of the engraved characters. Additionally, considering the fragility of the paint remains and to prevent further deterioration, the lighting level had to be dim, the humidity level set within the range of 55–65 percent, and the stone displayed within a showcase to prevent physical contact.

The intricate work on the markers has shown that, though largely invisible to the public eye, the work of conservators is a highly demanding one. It requires a “keen understanding of material culture, and sensitive negotiation of the interconnection between an artefact[’s] materiality and social relationship throughout its history, in order to enable both it and its significance to persist”2. If not for conservators, our cultural artefacts will be lost to time and irreparable damage — and what are we, as a society, without our heritage?

Notes

1 The Hong Hin boundary marker is still undergoing treatment for conservation, which is expected to be completed in a few months.

2 Alison Bracker and Alison Richmond, Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths (Butterworth-Heinemann; V&A Museum, 2009), xiv.