Text by Dr John Kwok

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 3 – Jan 2017

Historical films are the most difficult types of film to make because in a way the script has already been written. Past events are immutable, which challenges the scriptwriter and director’s creativity, style and approach. Get it wrong and academics will challenge the film for historical inaccuracy or film critics will criticise its historical authenticity. The historian Mark Carnes reminds us that there is a difference between reel history and real history. According to his 2004 book Shooting (Down) the Past, Historians vs. Hollywood, reel history is comprehensible and accessible as it “unfolds according to the dramatic conventions with which audiences are familiar” and real history is complicated as the “plot lines skitter in every direction and seldom terminate in clear points”.

In 2016, as part of the celebrations for Singapore’s 50 years of independence, two filmmakers were commissioned to make two separate films about Pulau Ubin – an island situated on the northeast of Singapore’s main island. The island’s heyday was from the 1950s to the 1970s, when the island had a population of around 2,000, most of whom were working in the granite quarries or in supporting industries like the Food & Beverage industry. The population declined after the quarries closed down and the island took on a different role as the last of Singapore's island kampong community.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The first film – Homecoming, is by Singaporean filmmaker, Royston Tan. He was commissioned by the National Museum of Singapore to produce a film on Ubin as part of the National Heritage Board’s annual Singapore Heritage Festival. The film’s plot follows an old man as he travels back to Ubin to reconnect with his past. On his trip, he meets with people who are either working or living on the island and they share with him personal stories on their family background, how they arrived in Ubin and why they stayed. There is a feeling of nostalgia throughout the film as the old man revisits the places of his childhood and youth, only to discover that they have mostly vanished. At the broader level, the film reflects the way Singaporeans engage with heritage issues.

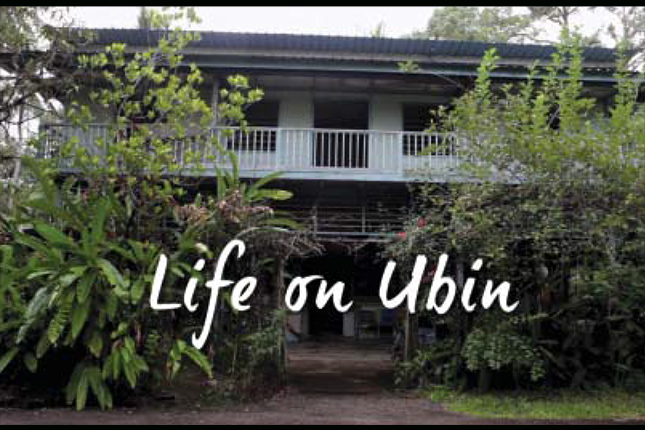

The second film – Life on Ubin, is made by budding independent filmmaker, Clarice Lee. She was commissioned to make a film as part of the National Heritage Board’s cultural mapping project.

Courtesy of Clarice Lee.

The story of Ubin is presented in a series of interviews with the residents of the island who share stories about their past and present lives on Ubin. This film does not have a central character or even a narrator to string together all of the narratives. Yet the narratives come together in a magical and charming way that tell the story of Ubin – past and present. It reflects the real history of the island community.

Courtesy of Clarice Lee.

Both films move in different directions to present the realities of life in Ubin and Singapore, succeeding realistically to portray a slice of Singapore's heritage from the perspective of Singaporeans in 2015 for audiences in the future. This is the power of historical films when the filmmakers get it right.

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Progress of ICH Survey

The National Heritage Board has embarked on a nationwide survey on intangible cultural heritage (ICH) in Singapore as of 2018. ICH elements such as oral traditions and expressions; performing arts; social practices, rituals and festive events; knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; and traditional craftsmanship will be surveyed in the project. This survey is running in tandem with the heritage survey covering tangible heritage in Singapore.

.ashx)