TL;DR

With 80 years now behind us since the Fall of Singapore, it is timely to examine the gaps in war memory, and perhaps to look further towards postmemory to enrich current narratives.

MUSESG Volume 15 Issue 1 – January 2022

Text by Iskander Mydin

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 15 Issue 1

This year is the 80th anniversary of the British surrender to the Japanese army in Singapore on 15 February 1942, also known as the Fall of Singapore. Much has since been written about the Fall, though with the hindsight of 80 years, much can now also be said about what is lacking in the corpus of literature relating to war memory. Besides paying attention to the missing voices, an examination of postmemory would enrich the discourse on war memory, which is especially timely as the generation of war survivors gradually passes on.

Transmission of Postmemory in Families

While the spotlight is often trained on the primary accounts of war survivors, there is in fact a great deal to unearth from the memories of war inherited by subsequent generations. These second-hand memories are referred to as postmemory, a term popularised by scholar Marianne Hirsch. Postmemory originally refers to the inheritance of war memories by the children of war survivors. It is applied in this article broadly to also include grandchildren of survivors. Succeeding generations negotiate with the narratives, images and behaviours of the survivors who are now gone; in turn, their own retelling of the event adds another dimension to the wealth of stories about the war, and enables them to avoid losing contact with the past.

The transmission of war memory across generations in the family is most likely carried out through anecdotal storytelling—in dialogue with another or as a cautionary tale from elder to younger. The latter then interprets and reconstructs the stories, and this provides a new layer to primary accounts. Additionally, how the stories were shared, received and treated as either meaningful or not is important in understanding how war memory is formed and sustained across time.

A section of the Surviving Syonan permanent exhibition on the Japanese Occupation, held at the National Museum of Singapore.

The following are some examples of postmemory encounters within the family. These experiences were shared by current and past National Museum of Singapore colleagues. First, a granddaughter has a vivid memory of her grandfather revealing his ill-treatment at the hands of Japanese soldiers and forbidding his family to purchase any Japanese-made goods for use at home.

Second, a son recalls that his father, born in the early 1950s and a football fan, would support any team playing against Japan or Germany, although he would also have some sympathy for Japan as an Asian country. He owned a Japanese-made car and the family bought Japanese household goods consistently. On the other hand, the maternal grandfather did not express any overt anti-Japanese sentiment, perhaps because he had worked for the Japanese as a driver during the war.

Third, a grandson did not inherit any memories of the war since both his parents and grandparents did not talk about it at all. And, finally, a granddaughter has only murky recollections from her grandfather.

Where there is little to no family transmission of war memories, the next generations are kept in the dark about what their elders might have gone through. The reasons for such exclusion may not be clear—the trauma was perhaps too painful to be revisited—but the end result is a lack of awareness of the impact of war on the families. Each of these examples highlights how transmission of memories may occur (or not) and thus how they are woven into a family’s biography of memories, which in turn enrich the overall tapestry of war memory in Singapore.

After the opening of the revamped Changi Chapel and Museum and Reflections at Bukit Chandu in 2021, there were enquiries addressed to the National Museum from descendants of former wartime officers. One was from the grandson of an Indian Army officer who fought in the Battle for Singapore and later won a Military Cross for his efforts in saving the lives of other wounded officers, and another from the grandson of a Malay non-commissioned officer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. With only fragmented memories to start with, both individuals were searching for more details and the personal artefacts of their grandparents’ war service. Thus, the museum is drawn into the realm of postmemory.

Defence medal awarded to war volunteer Julian Tay (NMS Z-0374). The museum hopes to reconnect these medals, donated in the 1980s, with the current descendants of the awardees.

Defence medal awarded to war volunteer Sahat bin Tahir (NMS Z-0371). The museum hopes to reconnect these medals, donated in the 1980s, with the current descendants of the awardees.

Within the National Museum’s collection are some war medals donated in the 1980s which the museum hopes to reconnect with the awardees’ descendants. In this way, the museum plays a role in expanding the postmemory of families. This can be especially meaningful for those who had little to no such encounters within their household. It is hoped that continued conversations on the war would spur younger generations to dig deeper into their family history and uncover the trove of (post)memories held by their grandparents or parents.

Contradictions of War Memory and Consumption

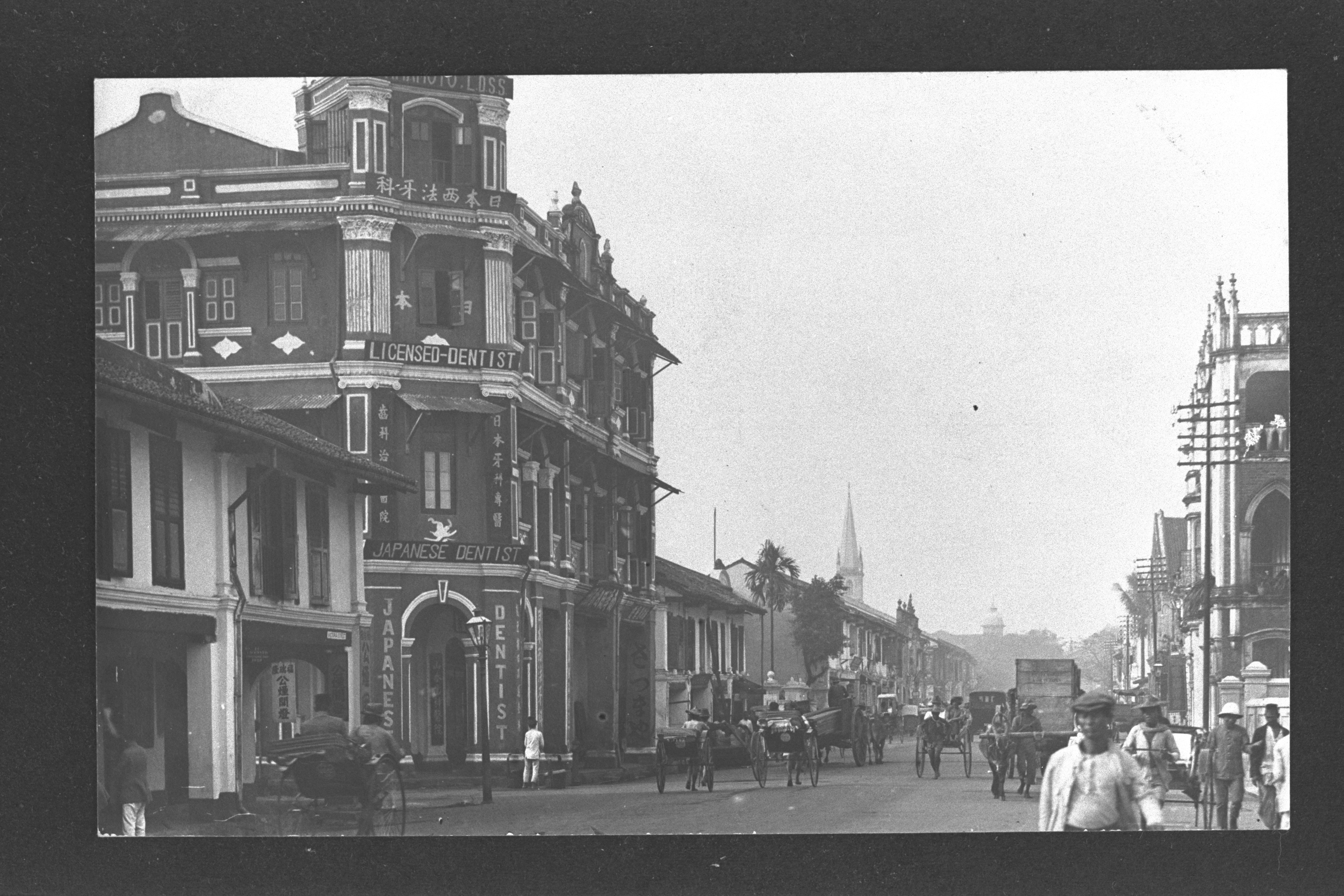

In the decades that followed the war, Singapore embarked on rapid industrialisation, and one of its strategies was to tap on the strengths and success of Japan’s industries. This saw the entry of Japanese-made goods such as rice cookers, electric fans and transistor radios into the local market, and these products became popular in many Singaporean households.

From the 1960s, as Singapore ramped up its economic development, Japanese-made products entered the local market. Many of these goods, such as rice cookers and cassette players, became popular household items. National brand rice cooker with original box, 1960s. NMS 2008-01550

From the 1960s, as Singapore ramped up its economic development, Japanese-made products entered the local market. Many of these goods, such as rice cookers and cassette players, became popular household items. Sony radio cassette recorder, 1970s–84. NMS 2010-04930

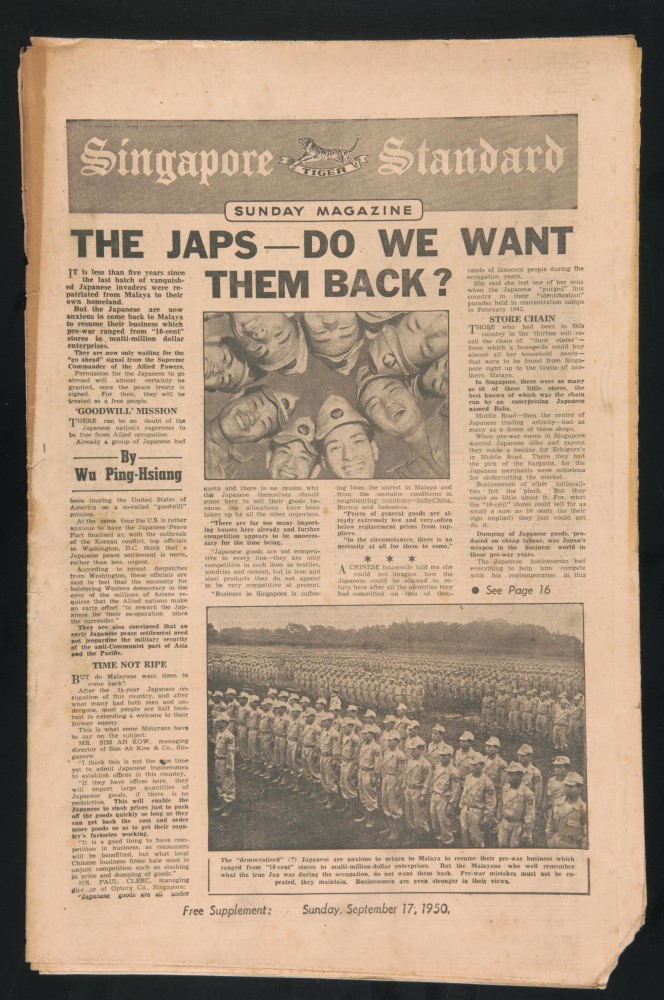

Interestingly, a survey conducted by the Singapore Standard newspaper in 1950 on the sentiments of local residents regarding a possible return of Japanese businesses to Singapore revealed a negative reaction. It appeared that the scars of the war remained fresh and the memory of the war was still too painful to be comfortable with Japanese businesses operating in Singapore.

Some of these commodities are now in the National Museum’s collection. With the above context in mind, the contradictions that exist within the self, as well as between the people’s war memory and the state’s pragmatic approach to postwar economic development and international relations, are laid bare. As such, the objects gain a new interpretive layer to their biographies as museum artefacts.

A survey conducted by the Singapore Standard in 1950 on the possible return of Japanese businesses to Singapore, 17 September 1950.1 NMS 2007-55180

Overlooked War Memory

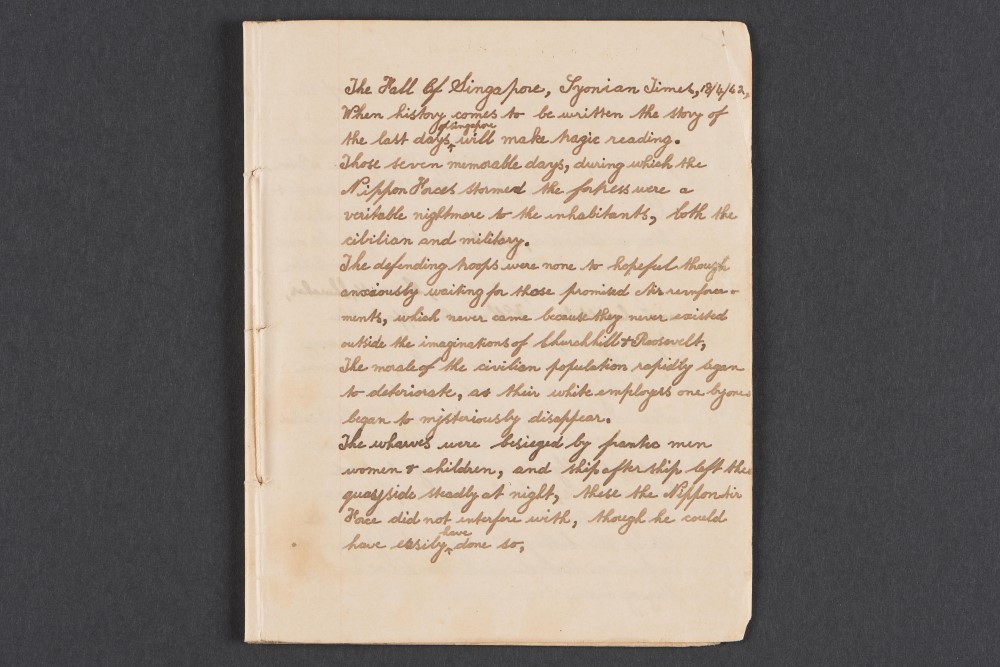

Under imprisonment in Changi, some prisoners of war and civilian internees documented their prison memories in the form of notebooks, sketches, diaries and so on, many of which have not been fully explored as war memory. One example comes from the surviving notebook of prisoner of war Sergeant John Ritchie Johnston, who wrote his recollections in the hope that a “history of the last days of Singapore” would come to be written.

Sergeant J.R. Johnston’s notebook in which he wrote his recollections of the “last days of Singapore”, 1942. The notebook is on display at the Changi Chapel and Museum. NMS 2018-00763

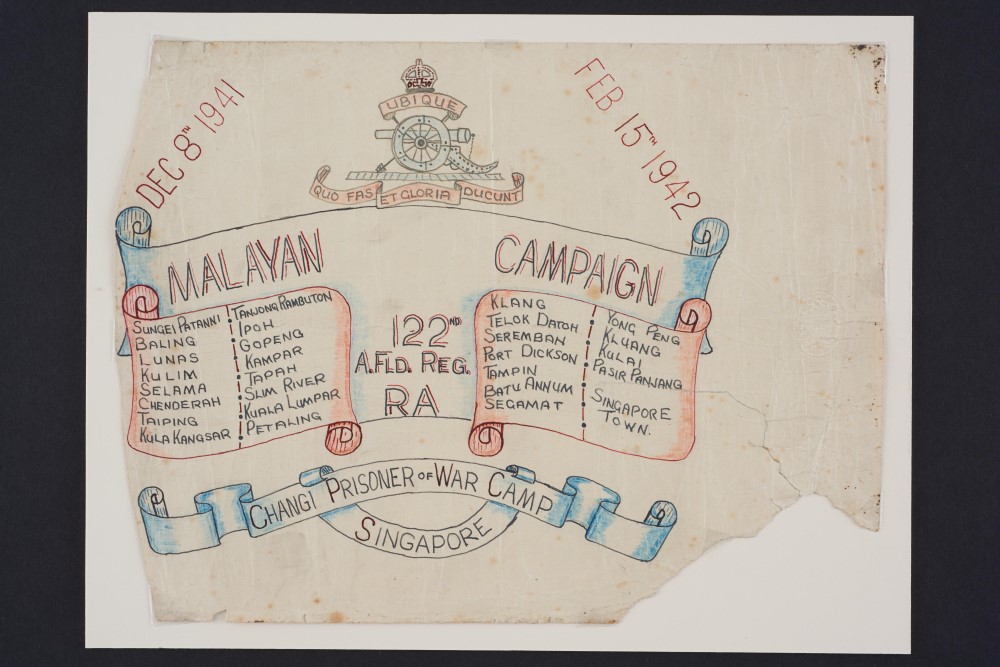

Another example is a sketch drawn like a plaque illustrating the battle trajectory of the Royal Artillery’s 122nd Field Regiment, from the regiment’s opening shots in December 1941 right up to the British surrender.

A sketch, artist unknown, illustrating the battle trajectory of the Royal Artillery’s 122nd Field Regiment, circa 1942. This drawing is on display at the Changi Chapel and Museum. NMS 2017-00299

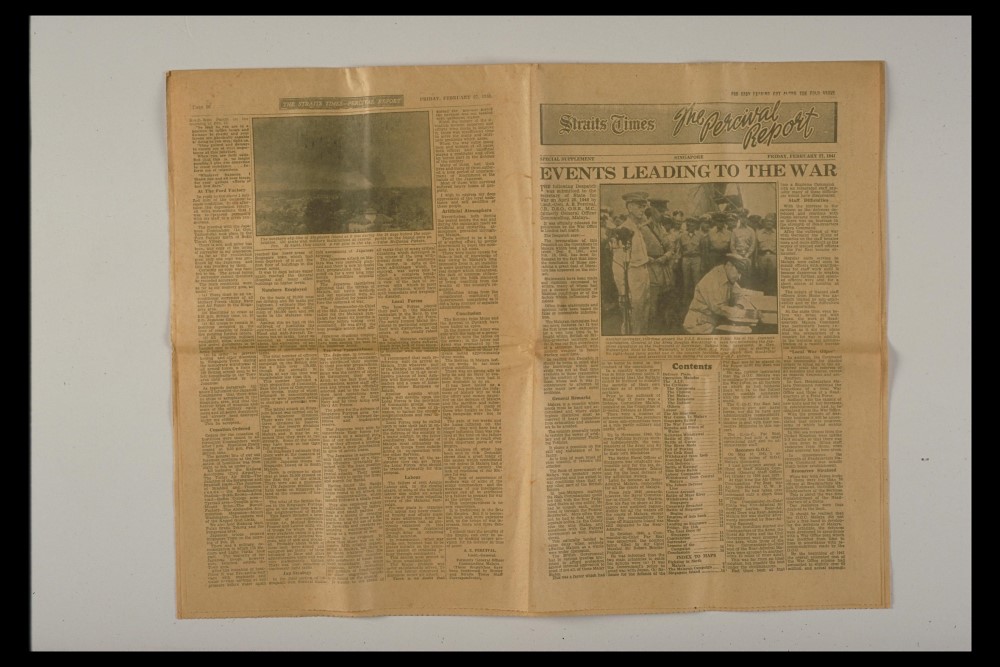

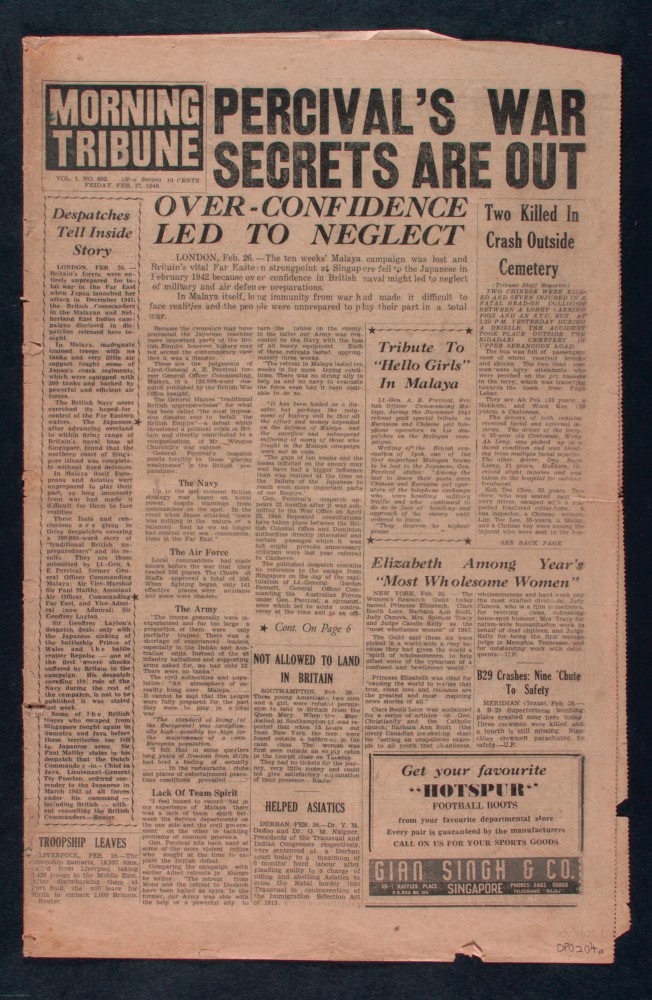

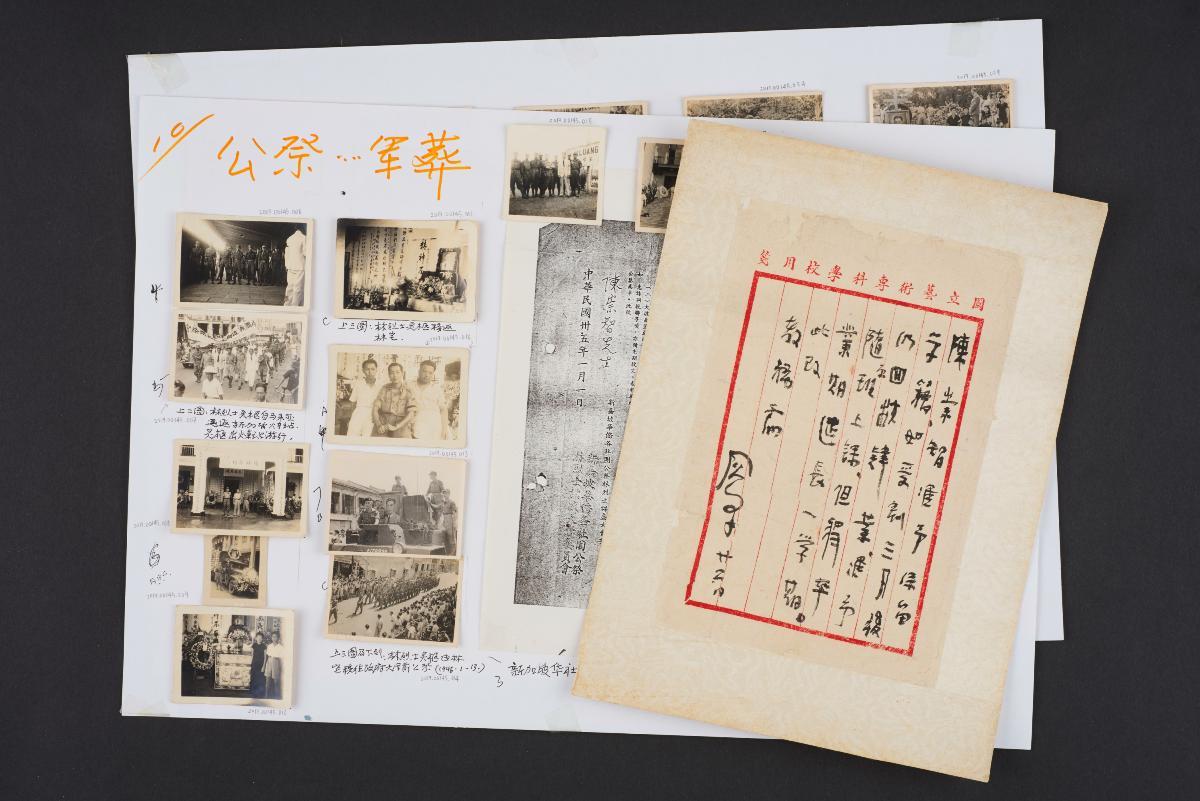

These forms of war memory-from-below deserve to have their place alongside the well-known war memoirs of generals, such as Why Singapore Fell (1944) by Australian commander General Gordon Bennett and The Road to Malaya (1949) by General Arthur Percival, as well as the latter’s earlier despatch published in British newspapers and in the local Straits Times in 1948.

The Straits Times, 27 February 1948, featuring a special supplement, ‘The Percival Report’, which provides General Arthur Percival’s account of the Malayan Campaign leading up to the British surrender. NMS 2001-00216-002

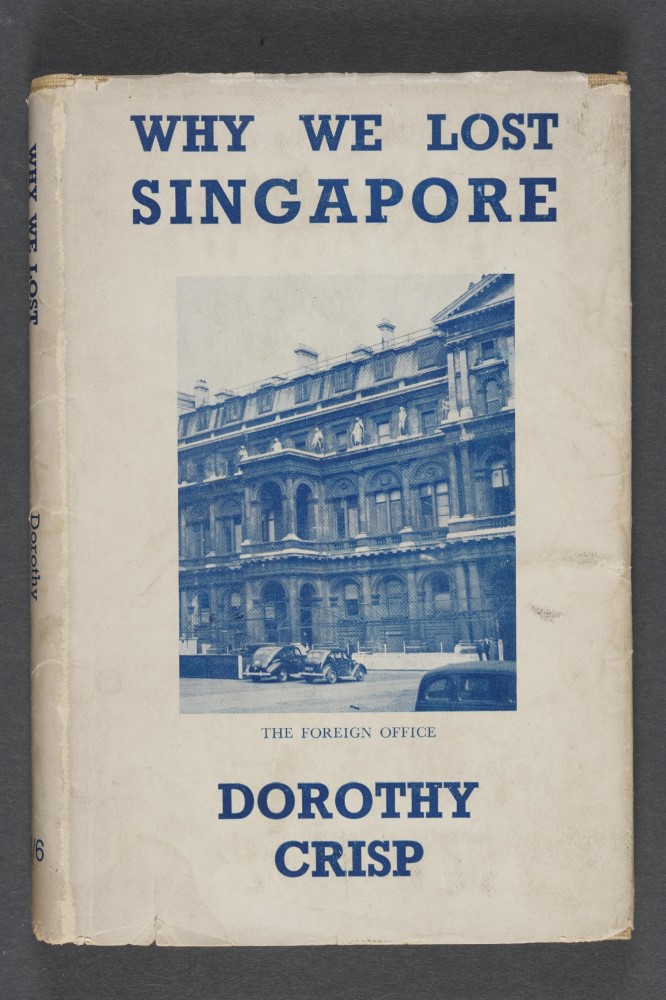

Another category of war memory that merits greater attention is the journalism of foreign war correspondents and newspaper columnists. These include war correspondent Ian Morrison’s coverage in his book Malayan Postscript (1942) written three months after the surrender; and columnist Dorothy Crisp’s wartime book, Why We Lost Singapore (1943), based on interviews with serving soldiers. Reading them now is to follow their narratives of the impending collapse and to re-enact in our minds those “last days”, in the words of Sergeant Johnston.

Newspaper columnist Dorothy Crisp wrote her wartime book, Why We Lost Singapore (1943), based on interviews with serving soldiers. NMS 2010-02709

Front page of the Morning Tribune, 27 February 1948, with General Arthur Percival’s take on the British defeat as the main story. NMS XXXX-03521-001

“These forms of war memory-from-below deserve to have their place alongside the well-known war memoirs of generals.”

Missing Voices

Although there is a seemingly vast amount of literature on war memory, compared to the volume of published accounts by European combatants, those of non-European combatants and local volunteers are still not on the same scale. In particular, notwithstanding some historians’ efforts to highlight the contributions of Indian Army contingents to the British war effort,1 the war memory of Indian Army soldiers in Singapore, who formed the largest contingent of Allied troops, has not been adequately covered.

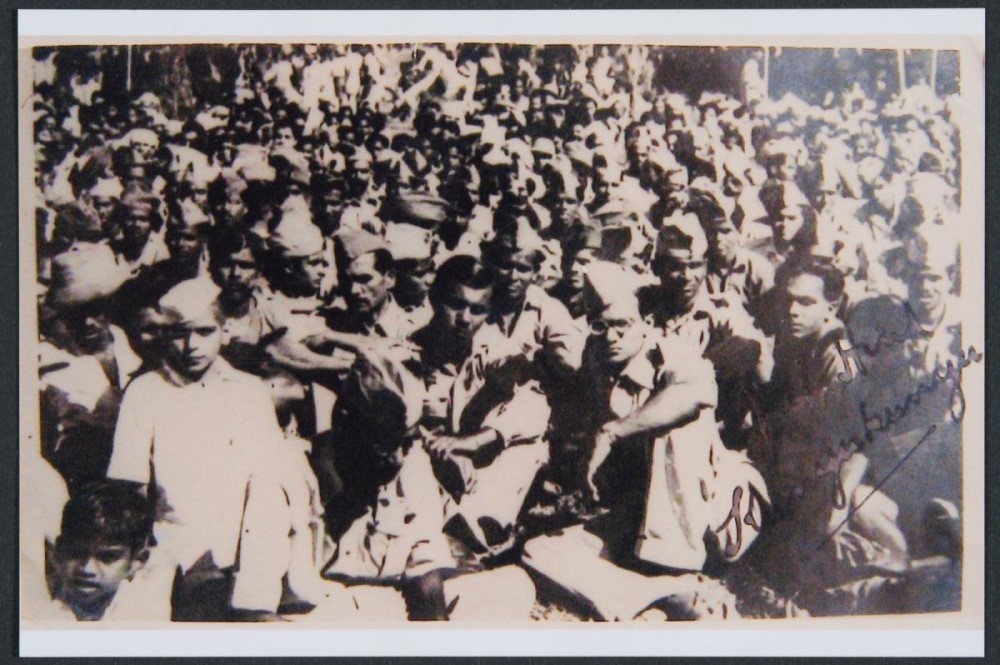

The surrender of the British resulted in 45,000 captured Indian Army soldiers, who were assembled on the field at Farrer Park on 17 February 1942 by the British commander on Japanese orders. It was here that the soldiers had to decide whether to remain as prisoners of war, or to join the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army (INA) at the urging of officers who had earlier gone over to the Japanese side. One soldier recounted his mental struggle the night before he decided to join INA and took a personal vow to free India.2 In his searing memory, Farrer Park was the birthplace of INA.3

Photography of INA Soldiers, Singapore/Malaya, c. 1940s, Collection of Indian Heritage Centre

This phase of INA’s history was subsumed by the re-emergence of an INA led by Subhas Chandra Bose in Japanese-occupied Singapore in 1943, which became the dominant postmemory of INA. It is perhaps timely to have a divergent reading of the overlooked Farrer Park assembly as a turning point in subaltern self-awakening for the mass of prisoners who chose to join INA, in contrast to the sense of loss and betrayal as expressed in much of British and Australian war memory.

Other perspectives that would also be worthwhile looking into are those of the descendants of local volunteer units including the Singapore Volunteer Corps, Dalforce and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve; and of civilians like the air-raid precaution wardens, nurses, firefighters and labourers who removed debris and retrieved corpses after Japanese aerial bombings. These war memories (or postmemories from their descendants) are necessboary to balance British and Australian war memory, and for the Asian subaltern to move from a peripheral position in war histories to a more nuanced one with some agency.

A Continued Resonance

Today, the Singapore Civil Defence Force sounds the public-warning siren throughout Singapore every 15 February at 6.20 pm (local time), marking the nation’s postmemory reminder of the surrender. Everyone in the city-state, young and old, is reminded of this dark period in Singapore’s history.

One cannot ignore the impact of the Fall of Singapore upon new generations. As we look back 80 years to the surrender, narratives big or small emerge, embedded within our family, the community and the nation. Commemoration, after all, is about retelling and remembering, and the act of doing so can be generative and meaningful. As long as succeeding generations are willing to engage with their postmemories, commemorative anniversaries can resonate even with the passage of time.

Notes

1 Yasmin Khan, India at War: The Subcontinent and the Second World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015); Srinath Raghavan, India’s War: The Making of Modern South Asia 1939–1945 (New York: Basic Books, 2016).

2 Gurbakhsh Singh Dhillon, From My Bones: Memoirs of Col. Gurbakhsh Singh Dhillon of the Indian National Army (including 1945 Red Fort Trial). (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 1999), 96.

3 Ibid., 541.

.ashx)