+65 Volume 2 – 2022

Text by

Choo Ruizhiof the S. Rajaratnam School of International

Studies (RSIS)

Read the full +65 publication here

In bak chor mee, babi pongteh, and Korean barbecues. In

restaurants, hawker centres, and kopitiams. In 2020 alone,

Singapore consumed 123,625 tonnes of pork, making it the most popular red

meat in the country.1 Yet none of this pork was raised locally,

because there have been no pig farms in Singapore since 1989.2

The pork Singaporeans eat today comes either chilled, frozen, or fresh from

over 20 different countries.3 Today, the only pigs left in

Singapore are wild boars which roam the forested fringes of the island.

Occasionally, these animals drift closer to human habitats, surfacing on

social media and newspaper articles.

Chua Mia Tee,

Amah Shopping in Chinatown (Pork Stall) 1977. Oil on canvas, 78.5 x 79.4 cm. Gift of Times Publishing Limited.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Today, the only pigs left in Singapore are wild boars which roam the

forested fringes of the island. Occasionally, these animals drift closer to

human habitats, surfacing on social media and newspaper articles.

Yet until as recently as the mid-1980s, over a million pigs were raised

annually in farms across Singapore, producing almost all the pork

Singaporeans consumed.4 Evolving government policies, however,

eventually determined that such self-sufficiency was not sustainable. The

local pork industry, though tremendously efficient, came at the expense of

other aspects of the country’s development, and was thus gradually

phased out.

Over the decades, Singapore’s policymakers have had to balance the

varying, sometimes conflicting demands of multiple stakeholders, so as to

ensure that different aspects of Singapore’s socioeconomic growth

could be managed. The local pork industry was one such area in which

disparate concerns about economic viability and environmental impact

intertwined, resulting in policy changes that markedly transformed how

Singaporeans obtained and consumed this protein. This short essay thus

surveys how changing sustainability considerations since the 1960s affected

pig farming in Singapore, leading ultimately to the imported pork

Singaporeans consume today.

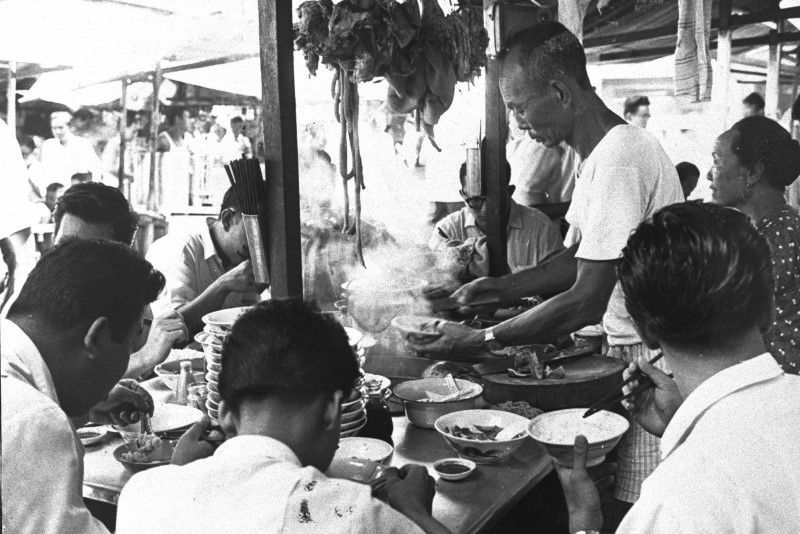

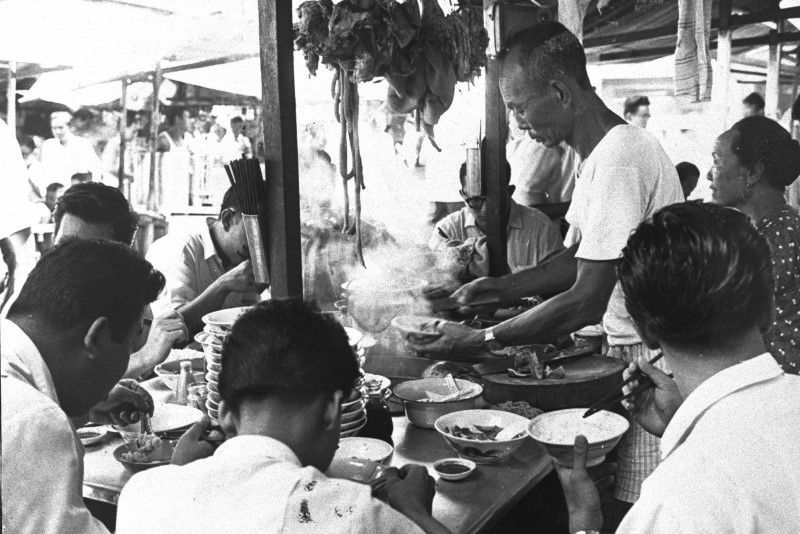

A street side hawker selling pork innards soup, 1965. Ministry of Culture

Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

A street side hawker selling pork innards soup, 1965. Ministry of Culture

Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

The 1960s: Food Self-sufficiency

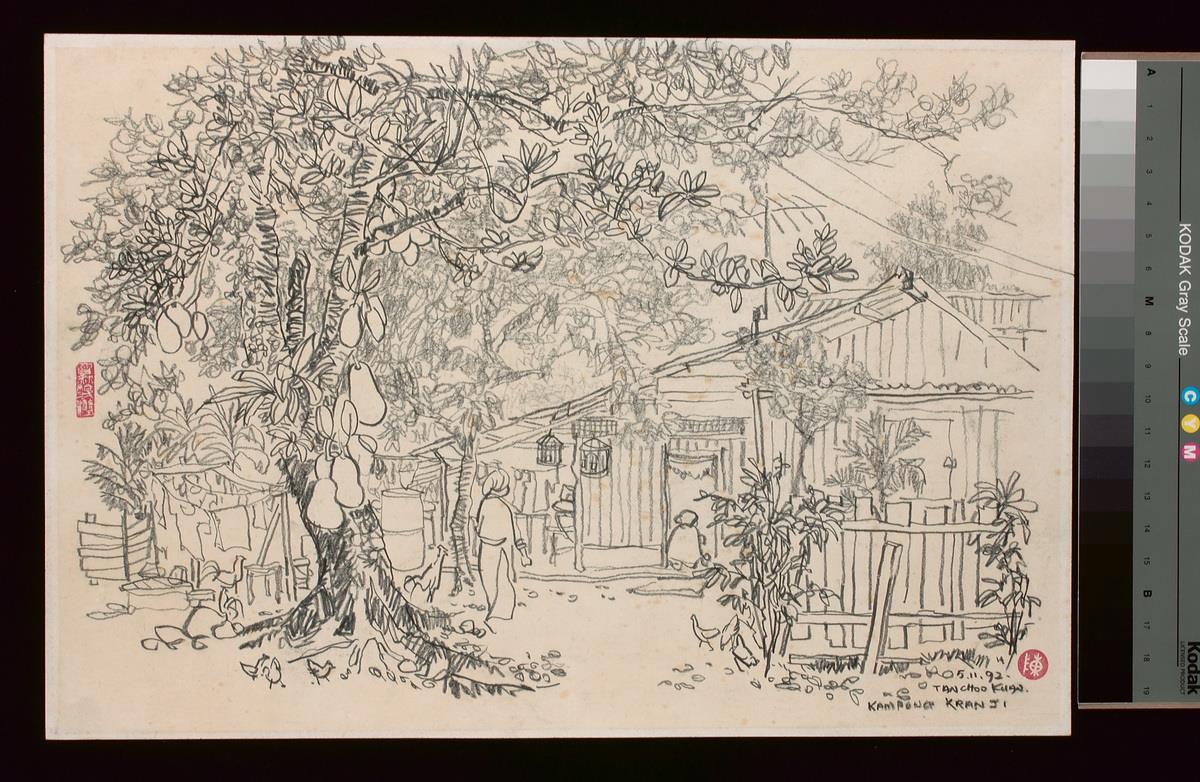

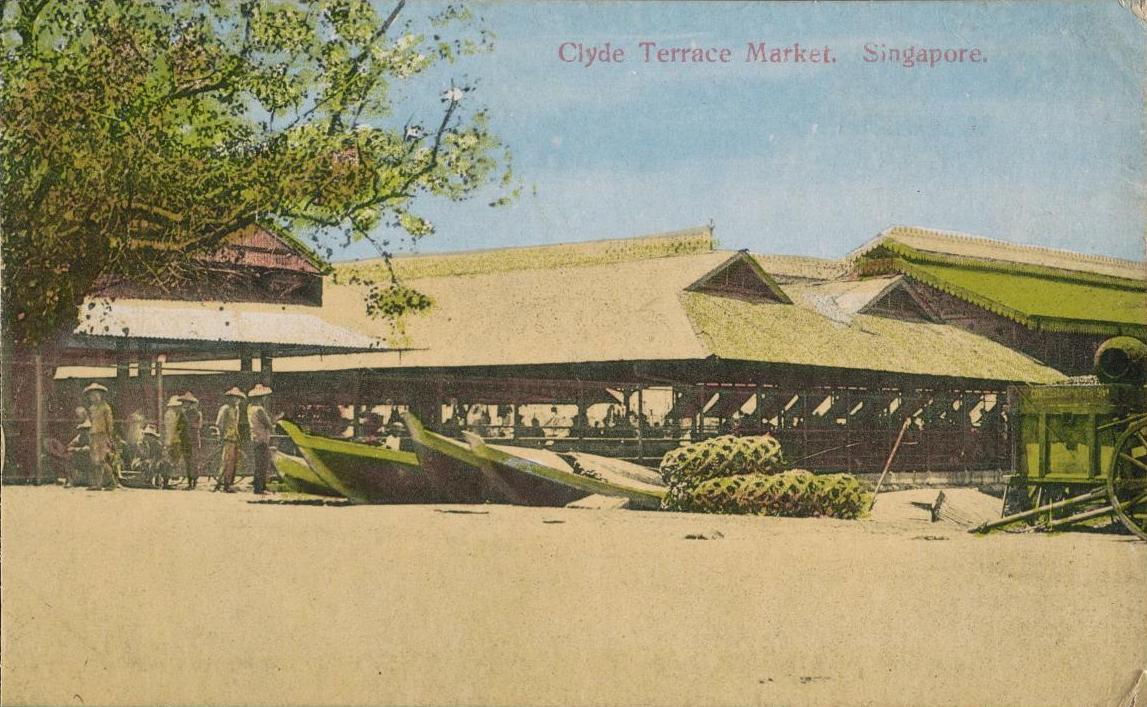

As compared to the present, Singapore in 1965 resembled a different

country. Sprawling expanses of farmland supported large rural communities,

and pig farms dotted the banks of the Kranji and Kallang rivers.

To help meet Singapore’s growing food needs, the then-Primary

Production Department (PPD) set out to improve the efficiency of existing

farms with better education and equipment.5 Lectures and study

trips were organised, while high-quality pig breeds and feedstock were

provided to farmers.6 In 1965, Singapore’s first farm

school was established in Sembawang.7

Taken together, these efforts saved the country “millions of dollars

in foreign exchange” by minimising the need to purchase imported

pork.8 But changes were on the horizon. Competing national

priorities meant that even efficient, small-scale farming could not be

sustained in the long run.

The 1970s: Competing Priorities

By the early 1970s, dramatic changes were occurring in Singapore’s

society, economy, and environment. In particular, Singapore’s meteoric

economic growth had begun generating tensions and trade-offs. Balanced

against other national priorities, pig farming in Singapore had to be

reorganised. Farmland shrank to make room for new factories, housing

estates, and military training grounds.

“We had about 6000 pigs before moving over here from Ang Mo Kio.

But with various facilities provided to us, we have an additional 4000

pigs now, after only about half a year of resettlement.”

-Tan Hong Chuay, owner of 3.25

–hectare farm with about 10,000 pigs, in a 1977 interview with

New Nation9

Meanwhile, to improve Singapore’s water security, large waterways

like the Kranji River were dammed to create reservoirs. Large farms in water

catchment areas such as Lim Chu Kang, Jurong, and Seletar were relocated to

newly-created farming estates in Tampines, Punggol, and Jalan Kayu to

prevent pig waste from contaminating new freshwater sources. Small-scale pig

farmers were encouraged to raise less pollutive livestock, or to give up

farming entirely.10 The era of intensive farming had

arrived.

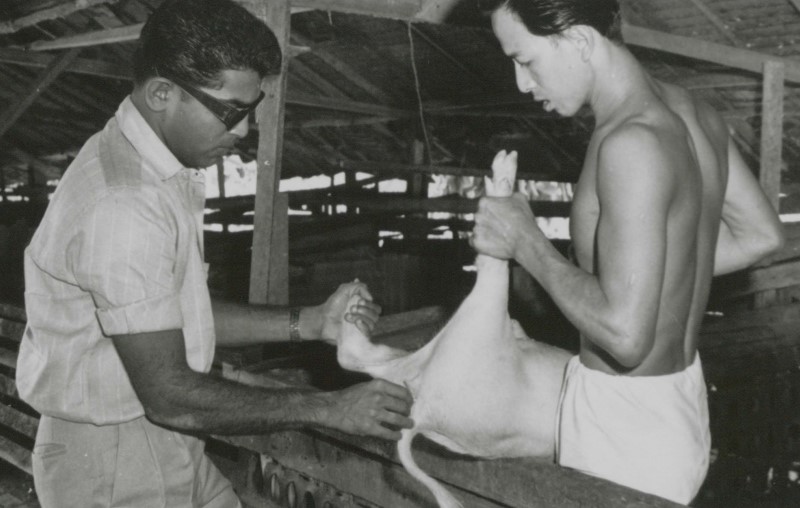

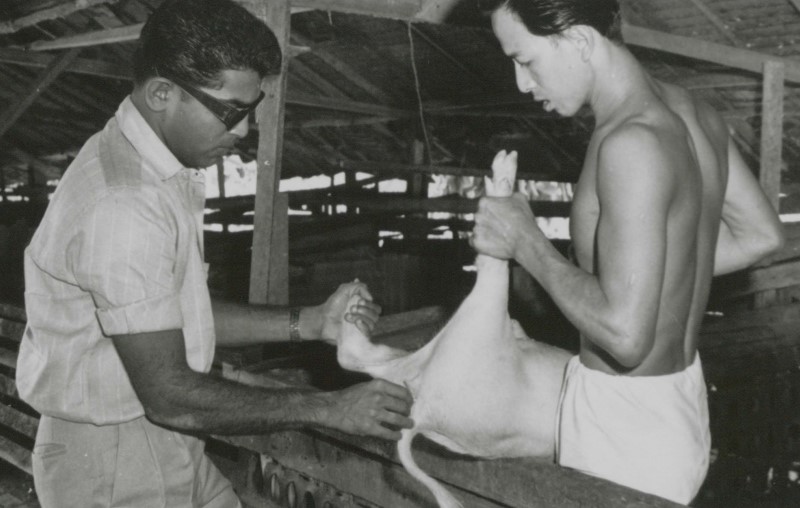

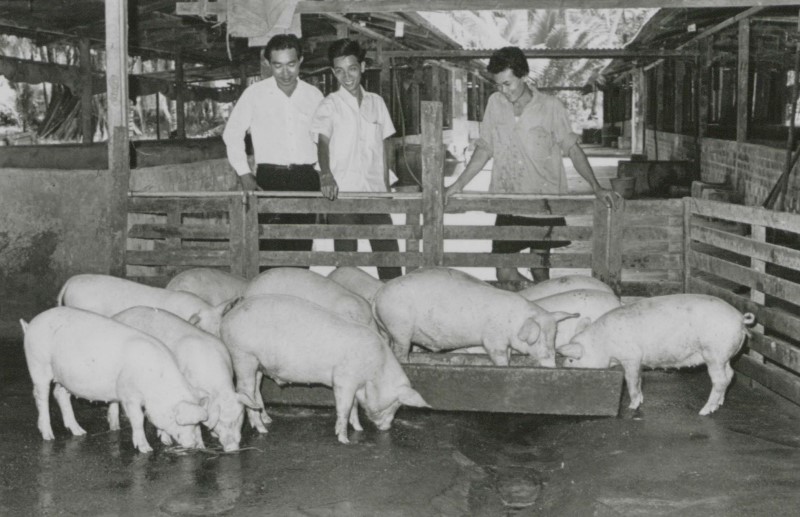

Pig farms, 1960s. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection,

courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Punggol Pork

One of the government’s most ambitious experiments in intensive

farming during this period was its development of the Punggol pig-farming

district. Over 1,000 hectares of land was allocated to this venture.

Electric cables and water pipes were laid, new roads were built, and

government flats constructed to house resettled farmers.11 The

Punggol Pig Centre, a laboratory specialising in pig diseases and pig farm

management, was also established in Jalan Serangoon Kechil.12

By 1977, the newly resettled pig farms in Punggol had considerably exceeded

production targets despite the decrease in available farmland. The PPD

declared Singapore “self-sufficient in pigs”.13 Intensifying pig farming with modern technologies had allowed for more

efficient, sustainable use of resources. By September 1980, Singaporean

farms were producing over 1.25 million pigs annually.14 Despite

these improved efficiencies, however, changes were soon afoot again. The

1980s would bring new choices and challenges.

“Does it make sense to spend some $80 million on waste treatment

plants to achieve poor environmental standards? If pig farms have

eventually to go, why prolong the agony?”

-Dr Goh Keng Swee, in response to a question filed in Parliament in

198415

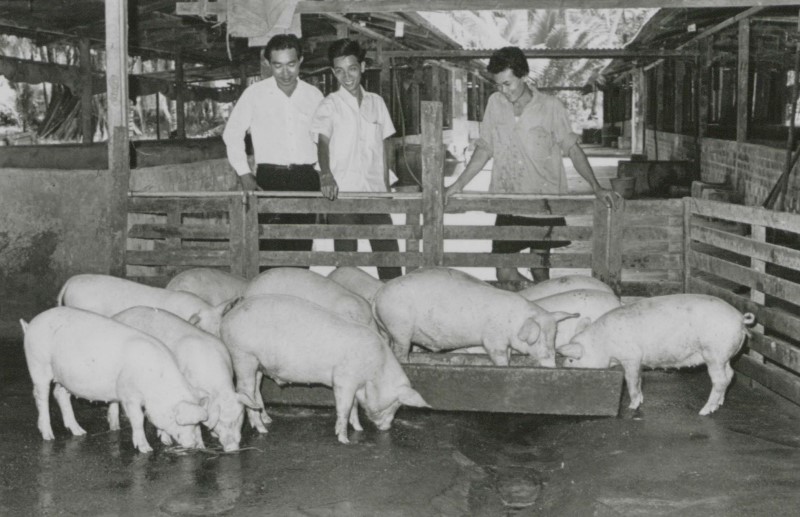

A pig farm at Punggol, 1970s. Collection of the National Museum of

Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The 1980s: The End of Singaporean Pork

Despite the local pork industry’s high production output,

policymakers by the early 1980s determined that pig farming was

unsustainable when balanced against other aspects of national

development.

In March 1984, Dr Goh Keng Swee, First Deputy Prime Minister, announced

that all local pig farms would be progressively phased out. All of

Singapore’s pork would henceforth be imported.16

“When they mentioned that they wanted to phase out the pig farming,

everybody was furious

… it really hit the farmers who are about 40, 50 years old …

when they are at this stage, you know, to tell them to go out and do other

business, it’s not easy.

My farm? We had to accept it, unwillingly, unfortunately. But that was the

government policy, so we had to stop.”

-Hay Soo Kheng, a pig farmer, in a 1991 interview with the National

Archives of Singapore17

After “a major review of pig policy”, the state had concluded

that the extreme toxicity of pig waste, expensive waste treatment plants,

and the resource-intensive nature of pig farming in general made it

economically and environmentally unsustainable in the long run. It would be

efficient, the government argued, to “supply the whole of our pork

requirements through imports, probably at a lower cost”.18

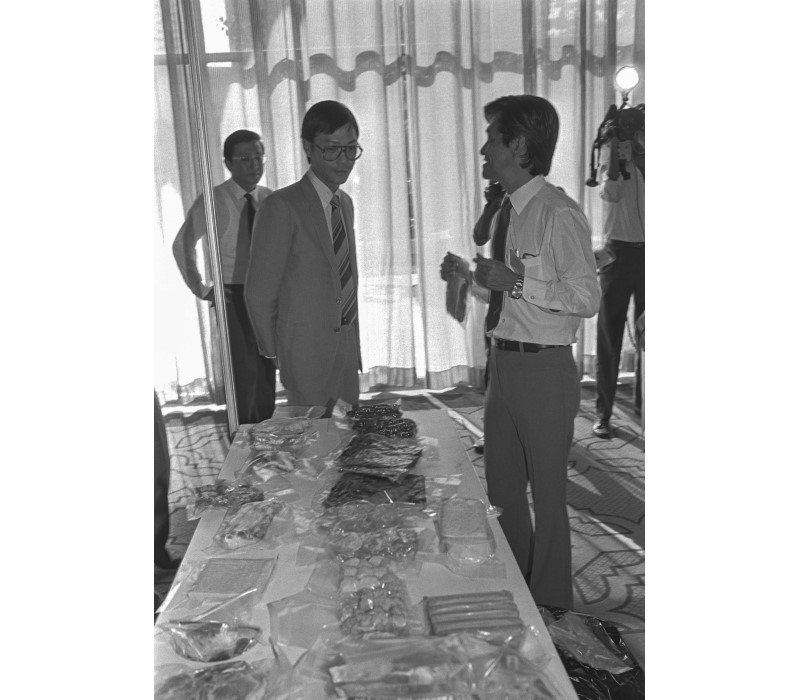

Minister without Portfolio Lim Chee Onn visiting a pig farm at Buangkok

South Farmway, 1983. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection,

courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

The decision had been made at the highest levels of government, who brooked

no protest to this difficult decision.19 Despite widespread

disappointment from farmers and even some PPD officers, the reaction to this

decision amongst most Singaporeans appeared to have been relatively

muted.

The ambivalent response might have been a product of broader shifts in

Singapore’s economy. Many small farmers had already been transiting

out of the pork industry for years, farming other crops, or exploring other

livelihoods due to diminishing state support for pig farming.

Rows of empty concrete pig enclosures at Lim Chu Kang Road, 1987. Housing

and Development Board Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of

Singapore.

For instance, stuck with excess pigs in his farms, Mr Lim Hock Chee turned

to selling chilled pork from a rented booth in a Savewell Supermarket outlet

at Ang Mo Kio in 1984, and was later able to take over the management of the

entire store. The decision marked the beginning of the Sheng Siong

supermarkets, which has today grown to an island wide chain of 61

outlets.20

“Now I’m 55. I have been farming since I was 18. What other

work can I do … The happiest thing in my life is that I have raised

eight children and I don’t owe anybody any money … That’s

not bad, isn’t it, considering I never learnt to read and

write?”

-Poh Ah Leck, owner of a small family-run pig farm, in a 1985 interview

with The Straits Times21

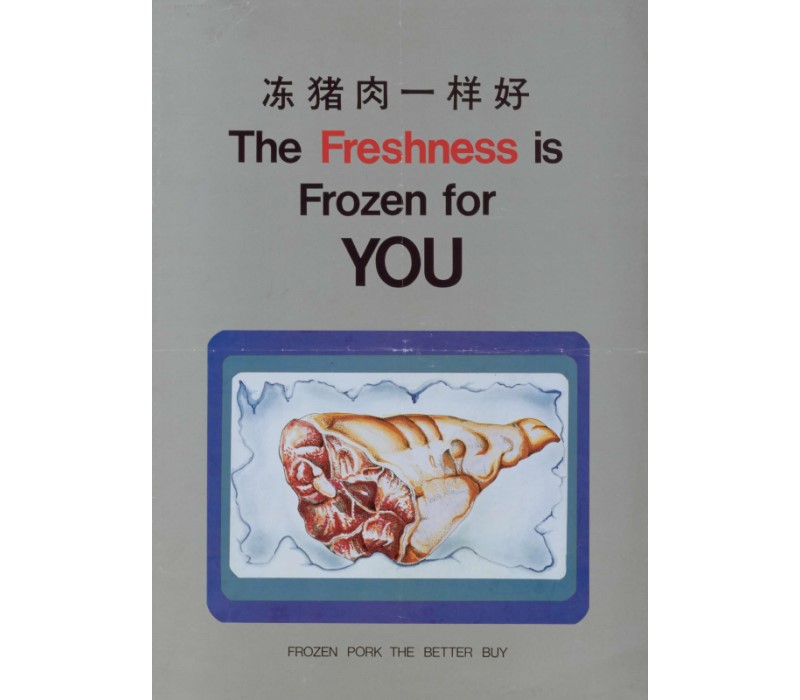

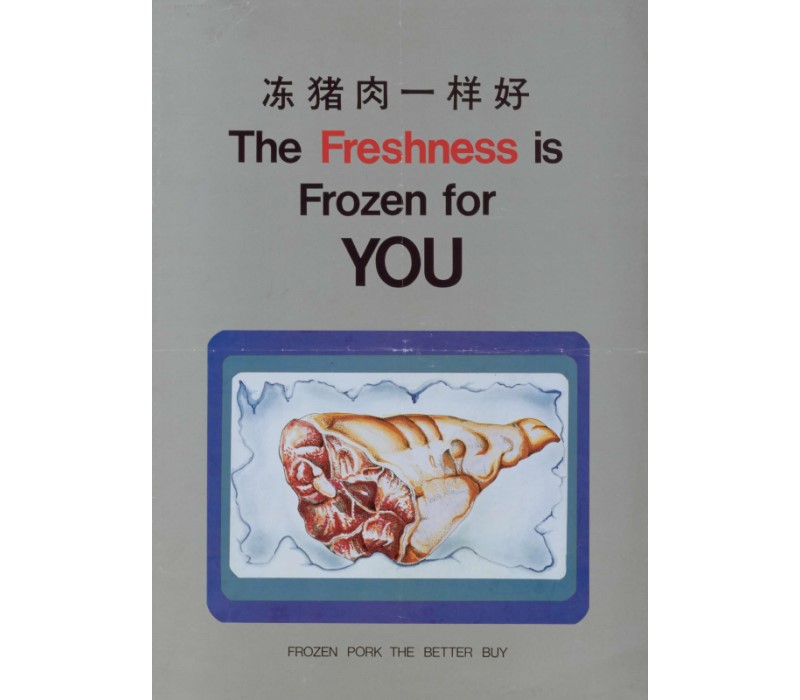

After phasing out pig farms, the Government was not idle either. In

addition to the monumental task of closing down local farms, PPD officials

fanned out throughout the region, seeking suppliers in Indonesia, Malaysia,

and Australia. New infrastructures were built to transport and market fresh,

chilled, and frozen pork locally. Publicity campaigns encouraged

Singaporeans to consume more imported pork.

Poster from the “Eat Frozen Pork Campaign”, 1985. Primary

Production Department Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of

Singapore.

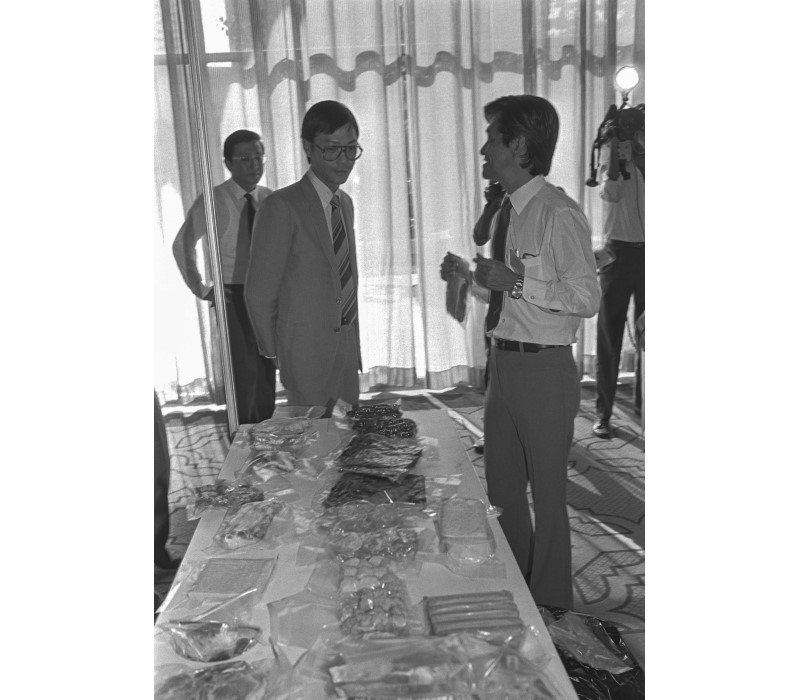

Member of Parliament for Jalan Besar, Dr Lee Boon Yang, at the “Eat

Frozen Pork Campaign” exhibition, 1985. Ministry of Information and

the Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

“Mr Lim Chye Joo, 82, said Primary Production Department (PPD)

workers came to his farm on Tuesday and put away two of his male pigs with

a lethal injection […] Mr Lim has 18 females and 12 piglets left.

He said PPD men will return on Monday to kill the rest.

‘It is not economical to sell them off because transportation costs

for such a small lot exceed any profits to be made,’ he said.

‘The female pigs are already old. There is no point trying to sell

the piglets off because farms in Punggol, Tampines, Changi and Sembawang are

being closed at the same time and the market will be flooded,’ he

added.”

An excerpt from “No market for these swine”, The New Paper,

26 Nov 198822

The era of Singaporean pork was over. Henceforth, Singaporeans (with

initial reluctance) would begin consuming pork, grown in overseas farms, in

increasing quantities.

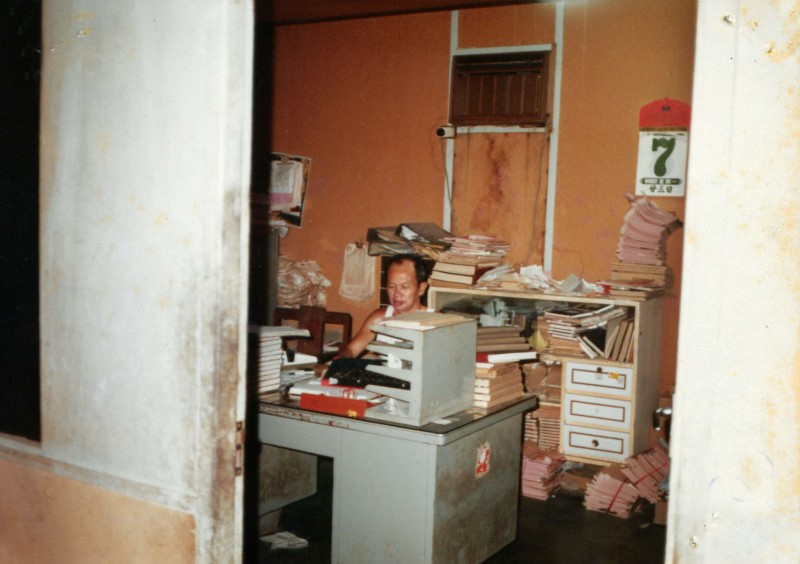

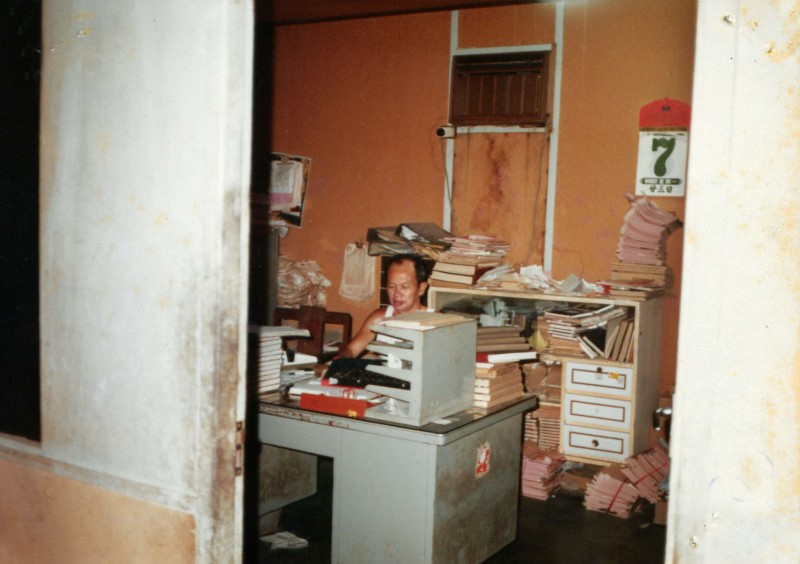

A pig farm owner in his office at Lim Chu Kang Road, 1985. Housing and

Development Board Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of

Singapore.

Singapore, Swine, and Sustainability

The story of Singaporean pork illustrates how stark choices had to be made

in Singapore’s early nation-building years, as leaders and citizens

alike strove to balance economic imperatives with growing concerns about

environmental sustainability. Entwined with these grand narratives of

national progress are hence also smaller stories of sacrifice, uncertainty,

and loss.

Yet policymakers and pig farmers alike met these challenges with tireless

determination and bold ingenuity, reinventing themselves to meet evolving

contexts. History cannot predict the future, but perhaps this brief story of

swine and sustainability shows us how we can likewise rise to meet the road

ahead: with grit, daring, and imagination.

Choo Ruizhi is a Senior Analyst in the National Security Studies Programme (NSSP) at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). He is interested in the histories of animals in colonial and early post-independence Singapore. In his free time, he likes to wander through Singapore’s past and present landscapes on foot, by bus, and in the archives.