Text by Low Sze Wee

Deputy Director (Heritage) Arts and Heritage Division

Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts

Images: National Heritage Board & Family of Cheong Soo Pieng

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 4 - Oct to Dec 2010

Cheong Soo Pieng (1917-1983) is generally regarded today as one of the most innovative and influential Singapore artists of the 20th century. Essays on him usually focus on his experimental spirit and formalistic innovations, often highlighting his synthesis of Western and Chinese art traditions. For an artist whose practice was so rich and diverse, there remain many fertile areas for future research, of which art patronage is one.

Artists do not live in a vacuum. In early 20th century Singapore, many China-born and trained artists such as Cheong had to initially make a living by teaching art full-time, either in an academy like the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) or local schools. This meant that they had little time for their own practice. Amongst the early NAFA lecturers in the 1940s and 1950s, only a few such as Cheong and Chen Wen Hsi (1906-1991) eventually had the good fortune of early retirement to become full-time artists. Nevertheless, they had to continue to give private art tuition, work on commissions or even start businesses (as in the case of Chen who owned two art galleries) to ensure an alternative income source. What gave them the confidence to give up their full-time jobs to pursue art must, in part, have been the support they received in Singapore and abroad from patrons whom they could count on to either buy their works or recommend them to other collectors.

In Cheong’s case, he started teaching at NAFA in 1947, one year after settling down in Singapore. He eventually left his job in 1961. Between 1946 and 1961, he held three successful solo shows in Singapore (1956), Kuala Lumpur and Penang (1957). He later travelled to Europe for two years and held exhibitions in London (Frost and Reed Gallery, 1962; Redfern Gallery, 1963), Munich (Galerie Schöninger, 1962) and Oxford (Bear Lane Gallery, 1963). In 1962, he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal by the Government of the State of Singapore. He was later honoured in 1967 with a retrospective exhibition at the National Art Gallery in Kuala Lumpur (his 12th solo show) in celebration of his 50th birthday and 25 years as an art teacher.

The support he received from patrons between the late 1940s and the early 1960s likely gave him the confidence and means to become a full-time artist who could travel around the world. This essay is a preliminary examination of Cheong’s practice in relation to the burgeoning art market during this period and especially his ties with a key patron from that era – Dato Loke Wan Tho. In particular, it will analyse some of Cheong’s works that were collected and later donated by Loke and his estate to the then National Museum of Singapore (now part of the National Heritage Board collection). Hopefully, future research will throw greater light on the critical roles played by various patrons in the development of Cheong’s practice and the reception of his works in Singapore and abroad.

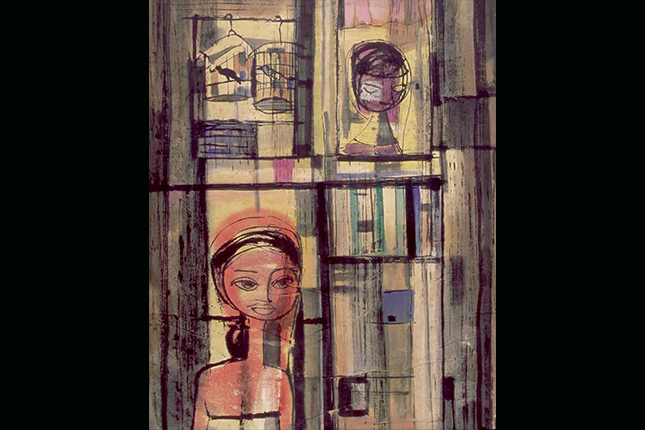

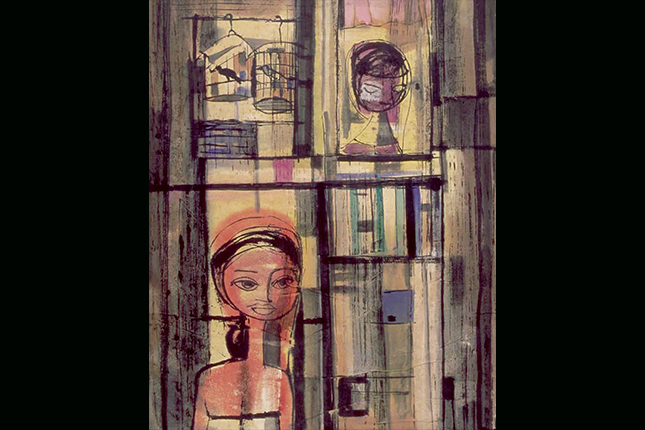

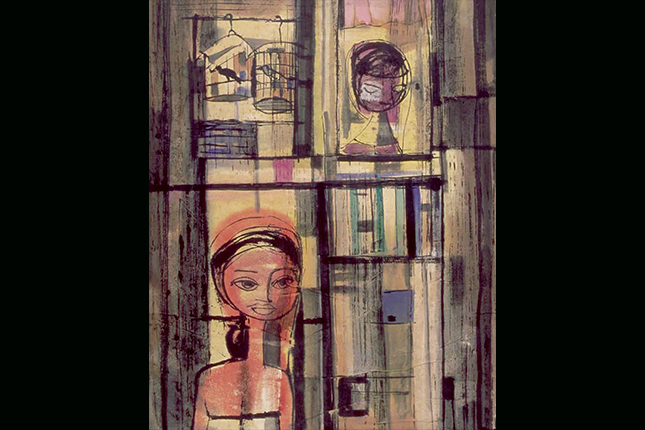

Cheong Soo Pieng, Untitled (Girl with Birdcage), Undated, 85 x 44 cm, Watercolour on paper. Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Untitled (Girl with Birdcage), Undated, 85 x 44 cm, Watercolour on paper. Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Art Scene in Singapore

After the devastation caused by World War II in Singapore, the local art scene slowly regained its footing. In 1946, teaching resumed at NAFA where Cheong became a teacher a year later. During that period, art groups like the Society of Chinese Artists re-established themselves, whilst new ones like the Singapore Art Society (SAS) and Society of Malay Artists (Persekutuan Pelukis Melayu) were set up in 1949. Such societies provided much-needed platforms for artistic exchange and joint exhibitions.

With the erosion of ties with China especially after the start of communist rule in 1949, the idea of a regional Malayan or Nanyang1 identity began to take root amongst the Chinese in Singapore. They started to identify themselves with the region, rather than the place of their birth. This was especially evident in literature and later, the visual arts. Interestingly, the need for a Malayan identity was also echoed by the British colonial government then. The Malayan Emergency took place from 1948 to 1960, during which the British government imposed severe measures to counter the communist insurgency in Malaya. The British also embarked on a cultural strategy to win the hearts and minds of the Malayan public against acts of terror by the Malayan Communist Party. In order to achieve this, the British hoped to create a shared Malayan culture to unite the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Brunei, Sarawak and North Borneo to stand against the Communist threat. Hence, the authorities worked closely with organisations like the SAS. For instance, in the 1950s, the British Council Hall was made available to many cultural and welfare groups, and the SAS even had its administrative office in the council premises.

In the 1950s, the concept of regionalism also dovetailed with growing nationalist sentiments and calls for decolonisation in the region as Singapore moved towards independence in 1965. This need for a Malayan identity continued even after Singapore gained self-government in 1959. One of the first ministries the new local government set up was the Ministry of Culture which was “vested with responsibility of formulating policies needed to create a common Malayan culture”.2

Art Market In Singapore

The abovementioned circumstances brought forth a flurry of exhibitions in Singapore, especially those organised by groups such as SAS. An editorial entitled “Singapore Wakes Up” in the 1955 SAS magazine reported, “It is probable that visual arts have received more attention and publicity in Singapore in the first eight weeks of 1955 than in any corresponding period in local history. There have been seven exhibitions, seven broadcasts, six public lectures, an unprecedented number of meetings of the various committees of Singapore Art Society, and The Singapore Artist has been widely bought and read.”3

In the 1940s and 1950s, there were no private art galleries in Singapore. Although venues like the Straits Commercial Art Company shop provided some space for artists like Cheong to display paintings, their primary business was not the sale of artworks. So, in those early years, exhibitions such as those organised by SAS provided critical opportunities for artists to show and sell their works to the public. For instance, the first exhibition held by SAS in 1950 featuring 278 works by 76 local artists, attracted over 6500 visitors and garnered sales of $3363.4

The buyers of such works then were mostly European expatriates and affluent locals. Amongst the more prominent in the former group were art promoter Frank Sullivan5 and art historian Michael Sullivan.6 In the latter group, the most famous was Dato Loke Wan Tho. Although there were other well-known collectors in Malaya then, like Tan Tsze Chor and Wong Man Sze, they tended to collect only Chinese art and antiquities, and had few or no works by contemporary Malayan artists like Cheong. The one exception was Loh Cheng Chuan from Penang who was not only a well-known collector of Chinese art but also a keen patron of local artists.

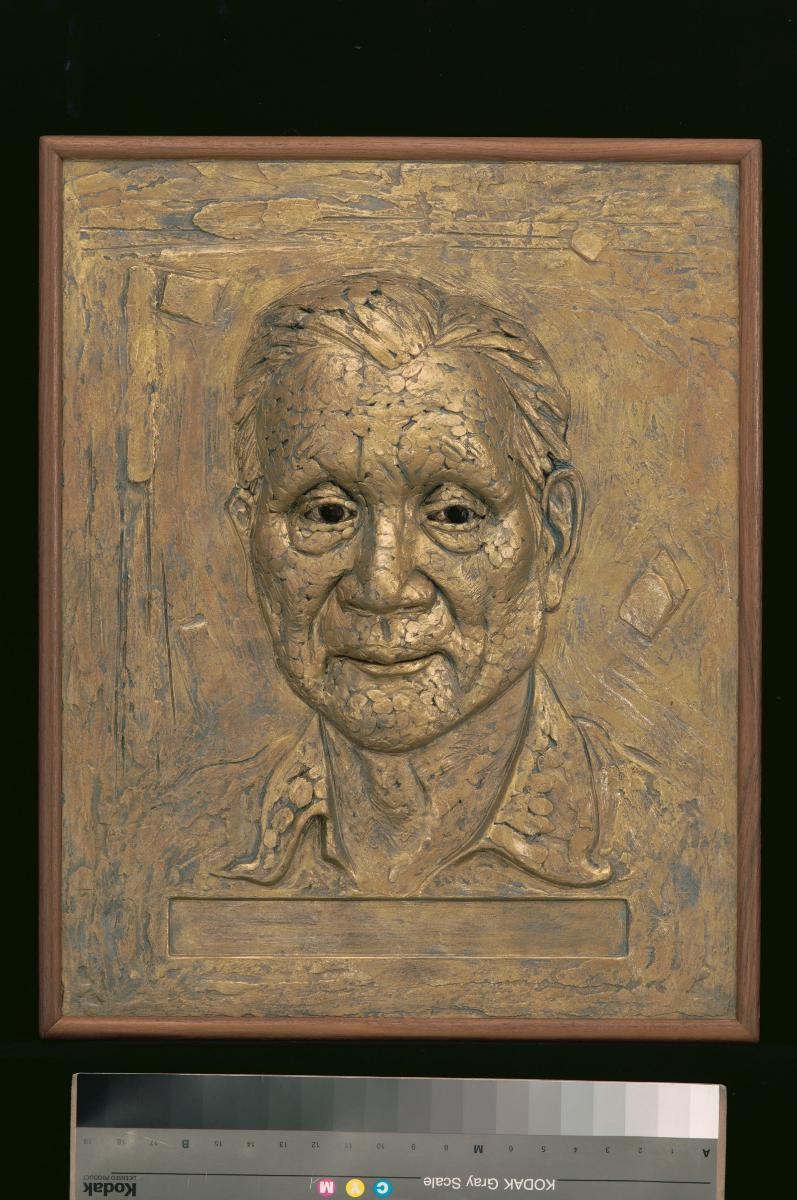

A Key Patron of The Era: Loke Wan Tho (1915 - 1964)

To many, the late Dato Loke Wan Tho is best known for leading the Cathay Organisation to become an important producer and distributor of Malay and Chinese films in the 1940s and 1950s. His regional business empire included cinemas, film studios and hotels. He was a much sought-after public figure and chairman of major institutions such as the Malayan Airways Ltd and Singapore Telephone Board. Often seen in the company of high government officials and glamorous film stars, he was very much one of the leading members of the Malayan establishment then.

Chua Mia Tee, Portrait of Dato Loke Wan Tho, 1995, Oil on canvas, 89 x 59 cm, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Chua Mia Tee, Portrait of Dato Loke Wan Tho, 1995, Oil on canvas, 89 x 59 cm, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Loke was a man of diverse interests and talents. A keen sportsman, he had a great love for nature. He was an accomplished ornithologist and photographer, and combined both interests to become an award-winning photographer of birds. Loke was also known as a great philanthropist. In particular, he was a tireless supporter of the arts and gave generously of his time and collections to various museums. Through his gifts, Loke supported the founding of the University Art Museum at the University of Malaya in the 1950s.7 As a collector, his interests were eclectic, ranging from Chinese ceramics8 to local modern art. In the latter, he was ably assisted by his personal secretary of 24 years, Ms Ann Talbot-Smith (1905-1983), who was herself also greatly interested in local artists.9

A sampling of Loke’s activities as an art patron in the 1950s and 1960s reveals that he was supportive of a wide range of local artists. He was the guest of honour for the opening of exhibitions by established artists such as Chen Wen Hsi10 as well as younger ones like Lu Chon Min.11 For the latter group, these shows mattered a great deal as the artists often relied on the sales proceeds of such exhibitions to fund their overseas studies.12

By the early 1950s, Loke was already active with the SAS, having organised its first photographic exhibition with his good friend and SAS president Dr Carl Gibson-Hill in 1950. And Loke continued to maintain close ties with the SAS through the 1950s and early 1960s. For instance, besides serving as patron of the society in 1960,13 he also opened many of its shows as guest of honour and bought many works at such events. Loke’s secretary Talbot-Smith was also closely associated with the SAS, having served as its secretary for a time.14

By the late 1950s, Loke was regarded as having Singapore’s largest collection of works by local artists, numbering some 80 works. This was later augmented in 1957 by his purchase of another 64 works from Frank Sullivan who was then SAS vice-president.15 Loke had planned to display them with his own collection in Singapore’s first community art gallery.16 This eventually culminated in Loke’s decision to donate 99 paintings to the Ministry of Culture in 1960. The list of donated works by 50 artists included well-known names like Cheong as well as younger ones like Thomas Yeo.17 In 1962, Loke added 15 more paintings to the earlier 99 he gave.18 And after Loke’s untimely demise in 1964, his estate made another gift of his collection to the state.

Artist And Patron

When Cheong arrived from China in 1946, Loke was already based in Singapore, reviving his family’s cinema business after the war. At that time, Cheong was busy teaching at NAFA and had not yet had his first solo show in 1956. Although it is not clear when Loke first met Cheong, the latter was already taking part in group exhibitions then.19 Hence, it is likely that, given his interest in art, Loke would have encountered Cheong’s works at annual group exhibitions such as the one organised by the prominent Society of Chinese Artists in 1948 which featured an oil painting by Cheong of a female bather rendered in a cubist-like manner.20 In 1951, Cheong teamed up with Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee and Liu Kang, to present a group show called Four Artists from China organised by SAS.21 The same four artists held another group exhibition in 1953 under the auspices of SAS, after their 1952 trip to Bali. Again, it is highly probable that Loke, given his ties with SAS, would have heard of, if not seen Cheong’s works at both shows.

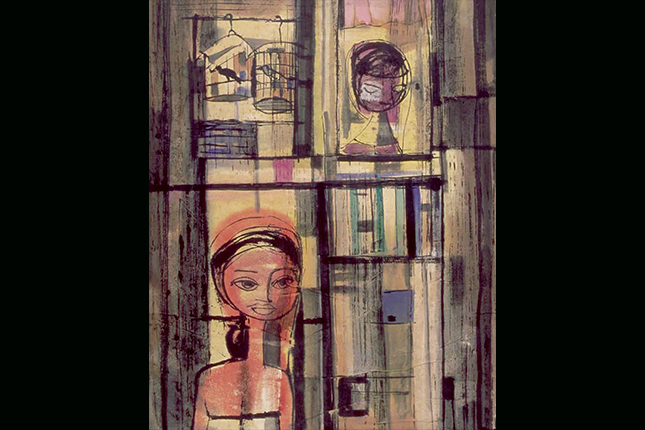

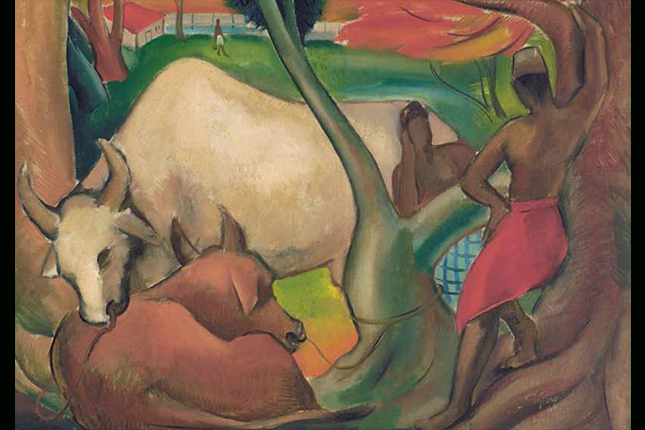

Amongst the works by Cheong donated by Loke, the earliest painting is Indian Men with Two Cows (1949). This was listed as ‘Kampong Scene’ and already in Loke’s collection when it was exhibited by the SAS in an exhibition titled Ten Years of Art in Singapore in 1956. However, it still does not provide the date of Loke’s first purchase of Cheong’s works as the painting could have been bought at any time between 1949 and 1956.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Indian Men with Two Cows, 1949. Oil on board, 76 x 105 cm. Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Indian Men with Two Cows, 1949. Oil on board, 76 x 105 cm. Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection Collection of National Heritage Board.

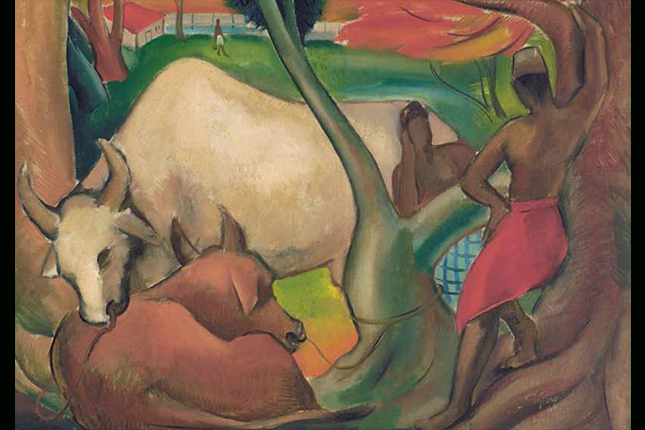

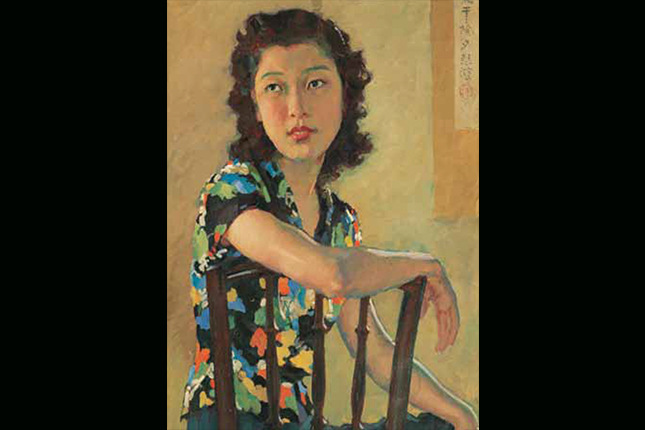

However, there is an ink portrait by Cheong of Loke’s second wife – the beautiful and glamorous Christina Lee – completed in 1953. This indicates that at least, by the early 1950s, Cheong was familiar enough with Loke to have completed a portrait of the latter’s wife.

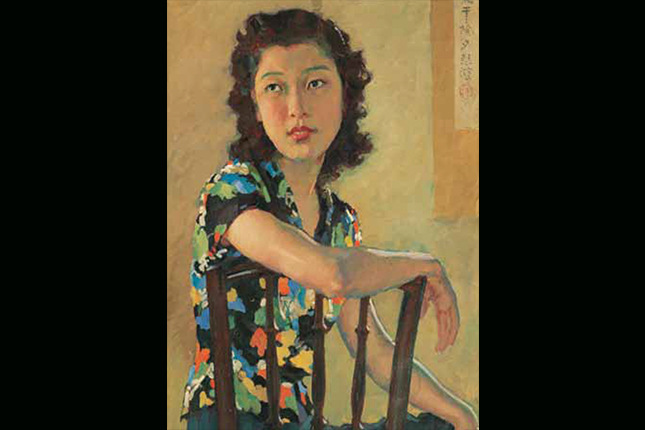

Cheong Soo Pieng, Portrait of Christina Lee, 1953. Ink and colour on paper, 75 x 54 cm, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Portrait of Christina Lee, 1953. Ink and colour on paper, 75 x 54 cm, Collection of National Heritage Board.

Apart from Cheong, Christina Lee was known to have posed for a number of famous artists including Xu Beihong, Basoeki Abdullah, Lee Man Fong and Sun Yee.22

Basoeki Abdullah, Untitled (Chinese Woman in White Cheongsum), Pastel, 66 x 51 cm

Basoeki Abdullah, Untitled (Chinese Woman in White Cheongsum), Pastel, 66 x 51 cm

Collection of National Heritage Board.

Xu Beihong, Portrait of Christina Lee, 1939, 82 x 54 cm, Oil on canvas. Collection of Xu Beihong Museum.

Xu Beihong, Portrait of Christina Lee, 1939, 82 x 54 cm, Oil on canvas. Collection of Xu Beihong Museum.

Three years later in 1956, Loke was the guest of honour at the opening of Cheong’s first solo show in Singapore. Organised by SAS at the British Council Gallery, the show featured a wide range of media, including oils, watercolours, batik, gouache, Chinese ink and sketches. It is helpful here to highlight the close connection between Loke and Frank Sullivan, as the latter was the SAS exhibition organiser for the said show. And again in 1963, Loke opened Cheong’s exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall in Singapore, showing mostly works completed after the artist’s trip to Europe in the preceding two years. The fact that Cheong invited Loke to be the guest of honour at his first solo show in Singapore and that Loke, a highly-regarded personality, twice agreed to officiate at Cheong’s shows, testify to the growing relationship between the two men.

(From left to right) Ho Kok Hoe, Cheong Soo Pieng, Mrs Cheong, Mrs Loke and Dato Loke Wan Tho at the artist's exhibition opening in 1963. Photograph from Cheong Soo Pieng catalogue (1991).

(From left to right) Ho Kok Hoe, Cheong Soo Pieng, Mrs Cheong, Mrs Loke and Dato Loke Wan Tho at the artist's exhibition opening in 1963. Photograph from Cheong Soo Pieng catalogue (1991).

It is highly probable that Loke would have shown his encouragement by purchasing Cheong’s works at such openings. By the 1950s, Loke was widely known in the art circles for his admiration and support of Cheong. He reportedly bought two to three paintings by Cheong every month and hung them in his office. Loke also gave some of those paintings to his business partners in Europe.23 Cheong’s daughter Leng Guat recalled that Loke’s secretary Talbot-Smith used to visit her father’s studio periodically to select paintings, usually Chinese ink, for such gifts.24 Talbot-Smith also sometimes brought Cathay’s guests to meet Cheong in his studio.25 His student Thomas Yeo recalled that in the late 1950s, many of Cheong’s collectors were either British expatriates living in Singapore or friends introduced by Loke. Occasionally, Frank Sullivan and Michael Sullivan also brought visitors to his studio.26

A number of Cheong’s mural commissions in the 1950s and 1960s such as those for Cathay Organisation (1955) and Singapore Telephone Board (1959), were also likely made possible through Loke’s connections.27 Loke’s support of Cheong in the 1950s during the Emergency period was helpful as this was a period when the British colonial government was generally suspicious of artists from China.28 Loke was well-regarded by the British elite in Singapore and on good terms with the then Commissioner-General for the United Kingdom in South East Asia, Malcolm MacDonald.29 The latter, who was also an admirer of Cheong’s works, bought paintings for his own collection as well as to give to friends during his tenure in Singapore between 1946 and 1955.30

Over time, Loke and Cheong developed a warm and easy-going relationship. They met fairly regularly, usually conversing in Cantonese. The Cheong family used to visit the Lokes during Chinese New Year.31 Cheong also dropped in, sometimes unannounced, on Loke at his Cathay office to either show new works, or introduce promising young artists to him. Despite his busy schedule, Loke often made time to meet Cheong.32 By the time Cheong left for Europe in 1962, he was already quite a successful artist and sufficiently well off to embark on a two-year long trip.33 Loke continued his support in various ways. During Cheong’s European trip, Loke together with others, helped to effect introductions to London galleries such as Frost and Reed, and Redfern, where Cheong eventually held his exhibitions.34 Through his networks with the media industry, Loke was also able to arrange a TV interview for Cheong in the United Kingdom.35 In addition, Loke used his wide business contacts to introduce Cheong to collectors in France and Italy.36

The Loke Collection

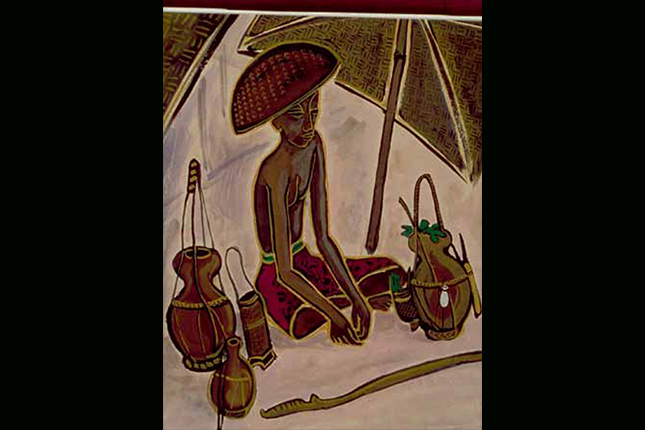

There are 12 works by Cheong in the NHB collection which were donated by Loke and his estate. Two paintings – Balinese Selling Toddy (1954) and Bali Beach (1955) – were most probably from the Frank Sullivan collection which Loke purchased in 1957.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Bali Beach, 1955, 50 x 63 cm, Oil on canvas, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Bequest. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Bali Beach, 1955, 50 x 63 cm, Oil on canvas, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Bequest. Collection of National Heritage Board.

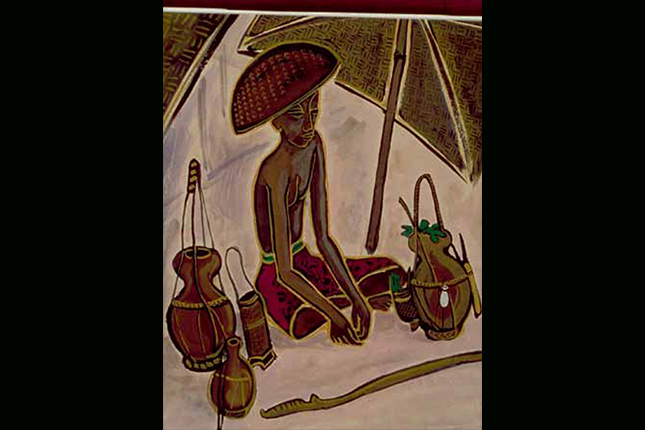

Cheong Soo Pieng, Balinese Selling Toddy, 1954, 46 x 37.5 cm, Watercolour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Balinese Selling Toddy, 1954, 46 x 37.5 cm, Watercolour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

These two works were likely acquired earlier by Sullivan when he helped to organise Cheong’s first solo show in Singapore in 1956.37 The 12 works do not represent an exhaustive list of Cheong’s paintings acquired by Loke. There are probably more works in the collections of Cathay Organisation and the extended Loke family.38 However, they do provide a useful glimpse into the range of paintings Cheong produced after his arrival in Singapore in 1946 and prior to Loke’s demise in 1964. They also reflect the types of works that attracted the attention of key patrons like Loke and Sullivan, and conceivably other collectors and admirers of the period. The latter would include personalities in Singapore such as Malcolm MacDonald, Michael Sullivan, Madeleine Enright, Ann Talbot-Smith and Ho Kok Hoe, and those in Malaysia like P.G. Lim, Kington Loo and Loh Cheng Chuan.39

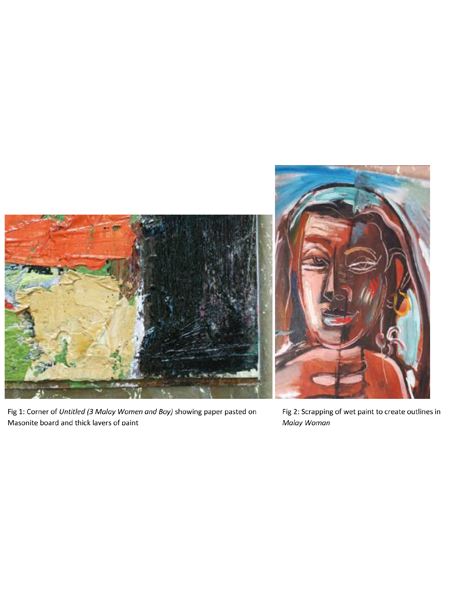

The paintings, evenly divided between six works done in oils and the rest on paper (either Chinese ink or watercolours), amply demonstrate Cheong’s proficiency in both Western and Chinese art traditions. Figurative works predominate, with only two landscapes and one still-life. Most of the figurative paintings feature scenes based on rural life such as Indian men tending cows or a Balinese selling toddy (a form of coconut wine). Others highlight local women (be they Malay, Balinese or Kenyah) in traditional dress. In these pictures, the women are usually shown against a backdrop of Southeast Asian motifs like palm fronds, tropical fruits, painted boats and oral patterned batik (a form of wax-resist dyed fabric).

The two landscapes depict scenes drawn from Cheong’s immediate surroundings. One shows a row of riverside shophouses – most likely along Singapore River – with boats and cars in the foreground. The other captures rustic wooden houses nestled amongst coconut trees with two Malay women in the foreground. These subjects convey an identity that is distinctly Southeast Asian. Consider the painting of a street vendor surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. The hawker’s loose singlet and wide-brimmed hat, together with the adjacent shirtless boy, hint at the hot and humid setting of the scene. Likewise for the painting of Singapore River – whilst the building facades may look European, the colourful green and red tongkangs (a form of cargo boats) bobbing in the waters are a reminder that such vessels are usually only found in this part of the world.

Such localised or Malayan themes were adopted by many local artists from the 1940s to the 1960s, both in response to their immediate physical environment as well as the growing interest in asserting a local identity. Such subjects were also consistent with the then British colonial authority’s attempts to create a shared Malayan culture amongst the local populace. Many expatriate collectors would have, understandably, also preferred works with explicitly local subjects as a reminder of the times they had spent in the region. As one of Cheong’s admirers Malcolm MacDonald had put it, “...whenever I contemplate one or another of them (Cheong’s paintings) I imagine that I had suddenly dropped in at a kampong in Malaya, a sea-shore resort on Singapore island, or a Dayak longhouse in the jungly interior of Sarawak.”40 Such was the evocative powers of Cheong’s works!

Lastly, an examination of three paintings featuring female figures (Bali Beach, Woman Lying Down and Untitled [Girl with Birdcage]) reveals Cheong’s innovative approaches between the late 1940s and early 1960s, which so captured his patrons’ attention. Whilst all three ostensibly depict similar subjects, the media and styles could not be more different. In the painting Bali Beach, Cheong demonstrated his proficiency with a Western medium, namely oil, and the stylistic features of key Western movements such as Primitivism, Cubism, Fauvism and Expressionism. He moved away from a straightforward representation of two topless women by reducing the female forms into simple graceful lines. The latter recall the sculpted features of indigenous wooden figurines as well as the rustic quality of the local way of life. The beach setting is captured by blocks of roughly applied brown, ochre and cream paint.

The blocks in turn form an interlocking design of angular planes which convey the effect of shifting light cast upon an undulating surface. Cheong also used strong bold colours, forming exaggerated contrasts, in order to accentuate the intensity of light and decorativeness of the tropics. Whilst the two ladies repose serenely on the beach, there is a sense of immediacy as certain elements such the boat, the basket of fruits and the lying woman’s feet have been cropped out by the picture’s edge, akin to the framing of a camera’s lens. The scene also pulsates with tropical fervour through Cheong’s application of paint in strong expressive strokes. Details like the patterns on the sarong (a loose garment made of a long strip of cloth wrapped around the body) worn by the seated female are sketched with quick fluid flourishes, suggestive of an individualistic spontaneity.

Cheong was also equally at home with Chinese ink painting. In Woman Lying Down, he used the long horizontal format associated with Chinese traditional hand scrolls. The latter are conventionally associated with landscape painting where a viewer is meant to experience travelling through the mountains and rivers as the landscape is slowly unrolled with the scroll. However, in this case, Cheong chose the subject of a reclining female which is usually more associated with the Western figurative paintings of Gauguin or Matisse, both known for their depictions of females in exotic locales. In this picture, Cheong had conveyed the feminine charm of his model through soft lyrical lines in ink. The Southeast Asian setting was captured through his careful attention to the woman’s elongated ears weighed down by heavy earrings and her oral patterned sarong. The figure’s affinity to nature is suggested by the large banana leaf on which she rests, whilst her rural occupation seems to be hinted at, by what appears to be a round woven tray in the background. The relatively flat colour washes used for the figure are in sharp contrast with her background which is completely filled with varying shades of ink. These, apart from bringing the female form into sharp relief, also provides an amorphous setting that alternately suggests receding depth as well as shifting light and shadow, constantly in flux.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Woman Lying Down, 1949, 37.5 x 94.5 cm, Chinese ink and colour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Woman Lying Down, 1949, 37.5 x 94.5 cm, Chinese ink and colour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Unlike Woman Lying Down which is a fairly representational depiction of a female figure, Cheong used a very different approach in the third work Untitled (Girl with Birdcage). It is also an ink painting but this time, the vertical composition is akin to the traditional hanging scroll format. Here, a standing woman is seen in the foreground and her Southeast Asian setting is suggested by her dress and headwear. The female form is now somewhat distorted through the elongation of her neck and arms as well as her heavily lidded eyes. Another person is seen peering through a curtained window in the top left corner of the painting, beside which hangs two birdcages, a common sight in many rural Malay homes. In this work, Cheong departed from Chinese painting aesthetics which conventionally dictate that parts of the paper surface should be left unpainted to suggest the physical setting of subjects, be it the ground, sky or water. Here, Cheong had almost filled up the painting surface with a grid of heavy ink lines and blocks of greens, blues, purples, pinks, browns and greys. Most interestingly, Cheong integrated the two figures into the overall composition of rectilinear blocks, which even extended to the woman’s dress. The grid-like pattern recalls the abstract works of Mondrian but, at the same time, also conveys the patchwork quality seen in many wooden stilted houses in Malay villages. The latter often use wooden planks for construction of its walls, which are then painted in bright colours.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Untitled (Girl with Birdcage), Undated, 85 x 44 cm, Watercolour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Untitled (Girl with Birdcage), Undated, 85 x 44 cm, Watercolour on paper, Donated by Loke Wan Tho's Collection. Collection of National Heritage Board.

These three works amply exemplify how Cheong was able to bring together diverse media, techniques and approaches drawn from many art traditions, in order to capture slices of Southeast Asian life. In an era where the modern artist was celebrated for innovation, Cheong was able to assert his identity as a modern Asian artist in several ways. Firstly, his links with Asia were maintained through his foundation in Chinese ink painting tradition. At the same time, he was able to demonstrate his knowledge of international trends, particularly in Western modern art, both in his oil paintings as well as his innovative Chinese paintings. Thirdly, his Southeast Asian subjects also reflected his immediate reality, both physical and social, which in turn helped to connect him with his audiences in Singapore. As the art historian Michael Sullivan had succinctly put it in 1960, “His work is modern, yet not beyond the understanding of people of any feeling. It is influenced by modern art, but is by no means an imitation of it. It depicts the Malayan scene and yet does not merely illustrate or record it. It is, in fact, a true expression of the feelings of an artist who is at one with the world he lives in.”41

Note: The author wishes to express his appreciation to the following individuals who had kindly agreed to be interviewed for this essay: Ms Cheong Leng Guat, Mr Choy Weng Yang, Dr Ho Kok Hoe, Mr Tan Teo Kwang and Mr Thomas Yeo.

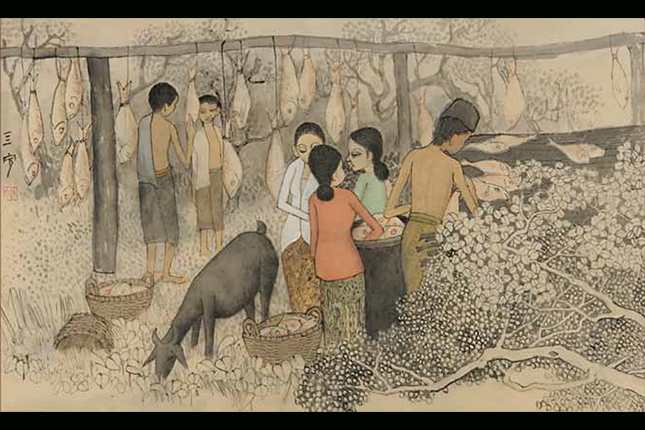

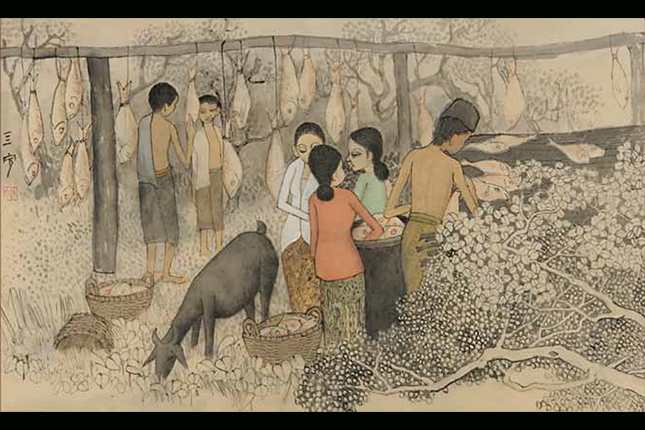

Take a closer look at Singapore’s $50 currency note and you will see a detail from Cheong Soo Pieng’s ‘Drying Salted Fish’. Designed for an arts theme, this currency note features the development and achievements of local artists.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Drying Salted Fish, 1978. 70 x 103 cm, Chinese ink and colour on cloth. Collection of National Heritage Board.

Cheong Soo Pieng, Drying Salted Fish, 1978. 70 x 103 cm, Chinese ink and colour on cloth. Collection of National Heritage Board.