TL;DR

Shanghai plaster is a stone-like facade finish highly popular in building construction from the 1920s-60s. Rarely seen on structures today, this plasterwork is a vestige of a bygone era.

MUSE SG January 2023

Text by Wan Pow Chween, Architectural Consultant, Preservation of Sites and Monuments, National Heritage Board

Read the full

MUSE

SG Jan 2023 Issue

Image above: The once-iconic skyline of Collyer Quay viewed from approaching steamships, 1969. Several of the commercial buildings along this stretch were embellished with Shanghai plaster on their exteriors to give them the look of expensive stone—at a fraction of the cost—and to evoke a sense of grandeur. Courtesy of Krystyn Olszweski

Natural stone is among the oldest and most durable materials used in building construction. Take for instance Rome’s majestic Pantheon, built in 25–27 BCE in granite as a temple for the gods—and still standing today in its full glory. Stone’s enduring aesthetic appeal lies in its stately grandeur derived from its properties of stability and solidity. Due to the prohibitive cost and labour it entailed, natural stone was mostly used in Europe for commercial and public edifices that represented political and economic power.

Today, there are no buildings in Singapore made fully of natural stone. However, it is easy to mistake several national monuments in the civic and financial district, such as the Former City Hall and Supreme Court as well as the Fullerton Hotel, as stone structures. These majestic neoclassical buildings are in fact made of reinforced concrete, though clad in a finish that gives them the appearance of expensive stone.

This stone-like finish is known as ‘Shanghai plaster’. Fourteen out of Singapore’s 75 national monuments feature extensive use of Shanghai plaster—a widely popular choice in local construction from the 1920s to ’60s. Rarely seen in new buildings today, Shanghai plaster represents the legacy of a material culture from a bygone era.

What is Shanghai Plaster?

Shanghai plaster is a type of cement-based finish developed in the late 19th century. Its innovation was facilitated by the widespread availability of modern Portland cement, a material patented in the UK in 1824. Prior to that, facades were mostly finished with a lime-based mortar mixed with other materials, such as sand and vegetable fibres like straw. With the advent of construction technology and the mass production of Portland cement in the late 19th century, new forms of cement-based plaster were popularised, including Shanghai plaster.

Also known as ‘granolithic finish’, Shanghai plaster is made of exposed finely crushed stone aggregates held together in a cement-based binder. The result is a textured or honed finish like masonry or faux stone. Indeed, by varying the aggregate mixture, Shanghai plaster can simulate the appearance of natural stone.

Since ancient times, facades and finishing materials have been manipulated to create the illusion of a ‘perfect’ appearance. The Romans, for example, decorated their buildings with a lime render that contained stone dust and pozzolana (a volcanic material) to replicate the texture of expensive marble. As the search for aesthetic perfection continued through the times, the idea of using granolithic stone proliferated across borders with architects drawing inspiration from Renaissance-era Italian and French architecture, and employing these styles in their buildings.

The main motivation for developing cement-based granolithic stone plastering was to embellish grey concrete, which was deemed unsightly, dull, and lacking in character. At the same time, the unavailability of a suitable paint for covering concrete also drove the innovation of this material. But the key reason for the popularity of granolithic finish in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was simply because it was more economical in terms of both material and labour costs compared to traditional stone masonry. In addition, granolithic finish was just as hardy compared to softer stones such as sandstone, limestone and some types of marble.

The ease of working with cement-based plasters also allowed for a variety of shapes and textures. When used together with steel reinforcement, granolithic plaster could be cast for architectural features such as cornices with wide overhangs, which was not possible with natural stone. This meant that granolithic finish became a choice material to accommodate rounded facades or more complicated architectural features more often seen in Western classical, neoclassical and Art Deco styles. With the large-scale commercial production of white Portland cement, Shanghai plaster became identified exclusively as an ornamental finish from the turn of the 20th century. Whereas the colour of Portland cement previously ranged from dark greenish grey to brown, the availability of white Portland cement now meant that Shanghai plaster could imitate almost any colour and hue of natural stone by the simple addition of mineral pigments.1 But due to the higher cost of white Portland cement, the use of Shanghai plaster as a finish was limited to external architectural ornamentation facings, particularly for civic and mercantile buildings of significance.

Why Shanghai?

Shanghai plaster did not originate from Shanghai, but was developed in Japan. The material is known by different names throughout the world, the most common being ‘granolithic finish’. But in Singapore, Malaya and Hong Kong, it was colloquially known as ‘Shanghai plaster’—a term that, interestingly, was never used in Shanghai itself.

One of the earliest mentions of ‘Shanghai plaster’ is found in the 1924 annual report of Hong Kong’s Public Works Department. In Singapore, however, there is no record of the term up until 1963, when a Straits Times article mentioned it. Prior to that, the finish was referred to by different names, such as ‘artificial stone plastering’,2 ‘granolithic facing’3 and ‘special plastering imitating stone’.4

It has been suggested that the ‘Shanghai’ label was derived from the Shanghainese craftsmen specialising in plasterwork who came to Southeast Asia to escape the Second Sino-Japanese War.5 Prior to the war, Shanghai had been a Foreign Concession split between Britain and the United States, where many European construction skills, including the use of granolithic finish, flourished. There are also claims that migrant workers from Shanghai first introduced the technique to Hong Kong, from where it was later exported to construction sectors in various Southeast Asian countries.6

In colonial Singapore, it was common for European architects to engage local contractors for construction work, who in turn hired migrant Chinese craftsmen. The latter included Shanghainese plasterers who were highly skilled in granolithic plastering, having learnt the technique in their home city. The spread of Shanghai plaster therefore represents not only the migration patterns of the Chinese diaspora, but also the concomitant transfer of skills and material culture.

As to why the term ‘Shanghai plaster’ gained traction in Singapore, it is likely that the label embodied certain positive connotations, such as the sense of cosmopolitanism that Shanghai represented, particularly during the interwar period from 1918 to 1939. The association of Shanghai plaster with modern, Western-influenced buildings along the city’s waterfront stretch known as the Bund and in other foreign concession zones or colonial territories was obvious: ‘Shanghai’ buildings were a symbol of the best of the West and the East. At the same time, goods that were not made in Shanghai were often passed off as such in order to give Asian consumers the impression that these goods were of superior quality.7

East Meets West: The Spread of Gronolithic Finish in Asia

Following the Meiji Restoration (1868–89), Japan saw a revolution of building styles: pseudo-Western classical architecture was now deemed highly desirable for institutional buildings, signalling Japan’s desire to project its emerging imperialist agenda. This was a hybrid style combining the Japanese tradition of post-and-beam structures with facades that imitated Western classical architecture.

Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons

To achieve this, Japan sought to develop a purely decorative finish based on a cement based granolithic plaster. As Japan is situated in an earthquake-prone region that is unsuitable for heavy masonry structures, a granolithic stone research institution was established in 1880 to develop artificial stone that would simulate the stone appearance of Western classical architecture. In the 1890s, the institute successfully developed its own granolithic finish known as jinzōishi nuri (人造石塗).

Soon, granolithic finish began to be used on major financial buildings in Japan, such as the Dai-Ichi Ginko (1906) in Kyoto, today’s central branch of Mizuho Bank, which combines stonelike cladding with red-brick pseudo-Western architecture. As Japan developed economically, the use of granolithic finish also gained popularity. Though originally seen as a cheaper substitute for granite stone, granolithic plastering gradually came to be appreciated for its own unique aesthetic form.

After the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), young Japanese architects were sent to Japanese colonial territories such as Taiwan and northeastern China to erect institutional buildings. In these places, granolithic finish was often the material of choice. It was used on buildings such as the distinctive Taipei Water Processing Plant (1908), known as Taipei City Water Museum today.

In 1916, Shanghai saw its first building with granolithic finish: the Union Building, which served Western financial institutions. In Shanghai, the material is referred to as shui shua shi (水刷石; literally ‘water-brushed stone’) or tai shi zi (汰石子). It was not long before other buildings along the Bund were also given the granolithic plaster treatment, such as the Glen Line Building and the Shanghai Club Building.

In Shanghai, however, not all buildings dressed in granolithic finish were built in the Western neoclassical style. Several privately owned buildings in Longmen Village, for instance, broke away from the Western form and adopted different architectural styles. One house in the village features dragon figurines made of granolithic finish, which signified a departure from Western tradition and the adoption of local influences. Granolithic plaster thus began to be integrated into local cultural contexts.

From Shanghai, the technique soon spread to British Hong Kong during the interwar years.8 Hybridised construction technology emerged as imported Western techniques were adapted to suit local purposes. For example, the Tang Chi Ngong Building (1931) in the University of Hong Kong features a Chinese traditional entrance arch finished with Shanghai plaster. Kau Yan Church (1932), on the other hand, wears a gothic revival style in granolithic finish. With the expanded use of Shanghai plaster in Hong Kong, the material transcended the imitation of Western neoclassical forms by acquiring its own modern aesthetic.

The Use of Shanghai Plaster in Singapore

As Shanghai plaster gained widespread popularity across colonial cities from the start of the 20th century, it made its way to British Malaya, which had flourishing commercial centres such as Singapore and Melaka. Naturally, the Western neoclassical architecture style was adopted for many important commercial and civic buildings in these towns to project the might of the British Empire.

After the First World War, downtown Singapore saw a major rebuilding. A dozen or more new office blocks, corporate headquarters and bank buildings were erected, while the British government also invested heavily in the construction of new public buildings. Shanghai plaster was the finishing of choice for these new structures as it offered the grandeur and prestige of granite at a fraction of the cost. Its appeal was also boosted by its qualities of durability and weather-resistance, and the flexibility of in-situ rendering and off-site precasting. Unsurprisingly, with all these advantages, the trend of using Shanghai plaster in architecture took off shortly after its introduction in Singapore in the early 1920s.

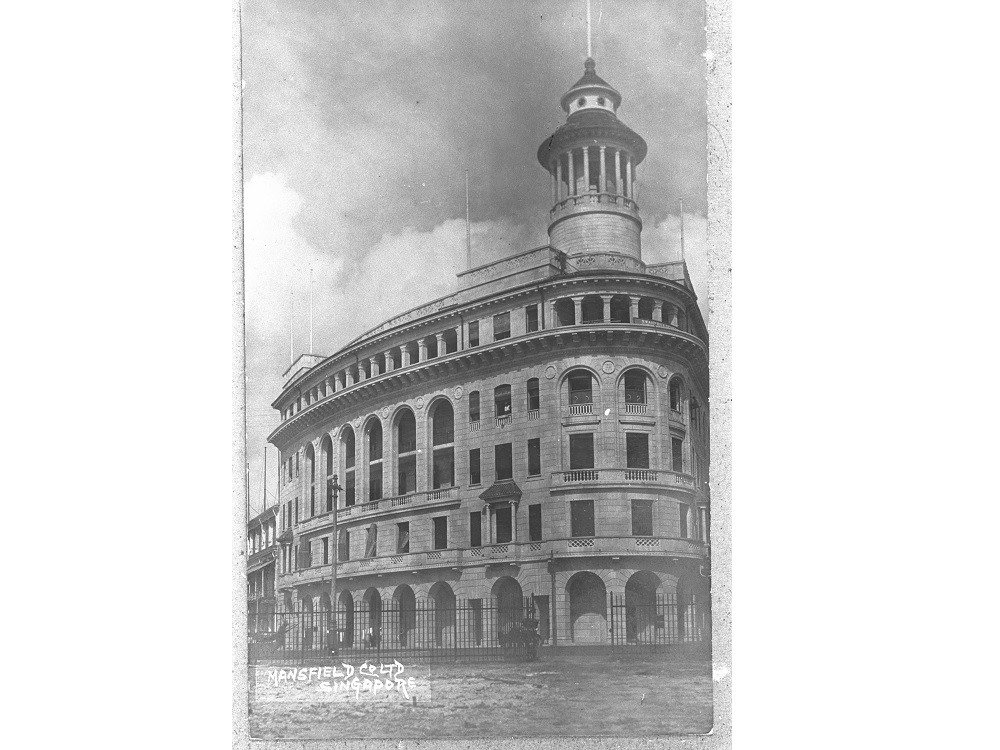

One of the earliest structures to feature Shanghai plaster was Ocean Building (1921–22) along Collyer Quay, commissioned by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company. Its plasterwork was carried out by renowned Italian sculptor Rudolfo Nolli. The rooftop of Ocean Building featured a freestanding pavilion cast in Shanghai plaster which highlighted the building’s corner with a striking silhouette. Ocean Building also marked the start of the new Singapore skyline, with a series of prominent structures erected in quick succession over the coming years along the waterfront of Collyer Quay.

With ornamental works adorned with granolithic finish in high demand, Nolli was commissioned for the plasterwork for a number of other seafront buildings, such as the Union Building (1924), Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (1924) and the Fullerton Building (1928). Together, these edifices came to define the new monumental character of Singapore’s skyline, particularly when viewed from ocean steamers approaching the harbour. Nolli’s most remarkable work, however, was the Fullerton Building (today’s Fullerton Hotel), which features an impressive row of free-standing fluted columns with Doric capitals precast in Shanghai plaster.

In the following decade, Nolli would achieve another two feats with Shanghai plaster: the Municipal Building (1929; renamed City Hall in 1951) and the Supreme Court (1939). These two imposing, magnificent civic buildings, which once symbolised British colonial might, remain as icons today and currently house the National Gallery Singapore.

Many of the Shanghai plaster-clad buildings were designed by architectural firm Swan & Maclaren, which was known for creating structures with a massive base and gigantic colonnades whose columns rose through two or more storeys, with equally large cornices and parapets—the Municipal Building (City Hall) being a prime example. Other works included the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, Union Building, Shell House, Overseas Union Centre and Clifford Pier—all of which were finished in Shanghai plaster.

Like many expatriate architects, Nolli employed a team of Chinese artisans in his workshop. He had arrived in Singapore from Bangkok in the early 1920s, bringing with him a number of skilled Chinese craftsmen. Nolli and his team used moulds to form granolithic tiles—a method that was not only economical but also offered the repeatability and consistency necessary for mass production.

Lina Brunner Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

By the 1930s, granolithic finish had clearly taken the local construction sector by storm. A 1937 Straits Times report described it thus:

The increasing popularity of bush hammered granolithic facings for buildings in Singapore is an indication of the extreme durability of this material under tropical conditions. The material has the advantage of not discolouring as it is composed of natural colours— local granite and white cement.9

As the Art Deco style became highly favoured between the 1930s and ’50s due to its modernist appeal, Shanghai plaster was even more sought after for its ability to add artistic touches to these buildings that typically featured sharp or rounded edges. Iconic Art Deco-style structures with granolithic finish include the Former Tanjong Pagar Railway Station (1932) and the Cathay Building (1939).

By then, the popularity of Shanghai plaster was no longer limited to spectacular financial and civic buildings in the town centre, but also used for shophouses and smaller mercantile buildings. Shophouses built in the 1940s and ’50s, for example, mostly wore the Art Deco style with Shanghai plasterwork as ornamentation. Some surviving examples include boutique hotel The Vagabond Club, a shophouse on Syed Alwi Road with yellow-tinted granolithic finish (1950); the former Dried Goods Guild building (1940) on Ann Siang Road; and various shophouses on Teo Hong Road. All of these are located in conservation areas.

Collyer Quay: Where Shanghai Plaster Reigned Supreme

RAFSA Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Collyer Quay is a street and seawall in Singapore’s city centre, stretching from the junction of Fullerton Road and Battery Road to D’Almeida Street. For over a century, the waterfront was an important landing point for the unloading and storage of goods transported along the Singapore River, and grew to become a vital link to the commercial centre.

Before its development, the Collyer Quay area was a beach. The seawall from Johnston’s Pier to the old Telok Ayer fish market was conceived of in 1858 by Captain George Chancellor Collyer, Chief Engineer of the Straits Settlements, while the land seaward of Commercial Square (later renamed Raffles Place) was reclaimed. Earth from nearby Mount Wallich was excavated to build the roadway behind the wall, and the road was named Collyer Quay upon its completion in 1864.

By 1866, a row of buildings had been erected along Collyer Quay. Due to its attractive seafront location and proximity to the commercial centre, the area saw rapid development in the 20th century with new structures built in quick succession. Many of these buildings were constructed with reinforced concrete and their facades clad in Shanghai plaster. The architecture at Collyer Quay came to define the skyline and image of Singapore until the 1980s.

Collyer Quay’s skyline in the 1960s and early ’70s was once dominated by the towering 15-storey Shell House (1959), Union Building (1924) and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (1924), all of which were designed by Swan & Maclaren. Other buildings embellished with Shanghai plaster along the waterfront included the Overseas Union Centre (1921) and Clifford Pier (1933).

As commercial buildings that served financial interests, these edifices wore a classical style made possible by the use of Shanghai plaster, which gave them an appearance of solidity and strength. Reflecting grandeur and prestige, the iconic skyline of Collyer Quay was a potent representation of the colony’s economic progress at the time.

Four National Monuments with Shanghai Plaster Finish

|

Former Ministry of Labour Building

|

|

Former Fullerton Building

|

|

Former City Hall

|

|

Former Supreme Court

|

The Decline of Shanghai Plaster

Granolithic finishing continued to be used in Singapore up until the 1960s when it fell out of favour. Modernity was now no longer signified by the gravitas of stone buildings but by the sheen of soaring glass-and-steel structures. Additionally, the labour-intensive craft of producing Shanghai plaster became a deterrent for contractors who wanted to build quickly and cheaply as Singapore’s economy boomed in the 1980s.

Tracing the history of Shanghai plaster reveals the extent of skill transfer that came with migration flows as well as the prevailing architectural trends of the early decades of the 20th century influenced by the British Empire. While many Shanghai plaster-clad buildings have been lost to redevelopment over the years, thankfully some still stand today as vestiges of a bygone era.

Notes

- William Samuel Gray, Concrete Surface Finishes, Renderings and Terrazzo (London: Concrete Publications Ltd, 1948), 117–20.

- [Advertisement], The Straits Times, 2 August 1935, 2.

- ‘Materials used in constructing Nunes and Medeiros’, The Straits Times, 5 October 1937, 2.

- [Advertisement], The Straits Times, 5 October 1937, 4.

- ‘The men who helped to build the new Supreme Court’, The Straits Times, 6 August 1939, 8.

- Ngai Sum-Yee, The Vanishing Link: Art Deco Architecture in Hong Kong Between 1920 to 1960 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University, 2004), 15–19.

- 杜中全 [Toh Teong-Chuan],《老槟 城.老生活》[Old Penang, Old Life] (Selangor: 大将出版社, 2012), 32.

- Lai Chun Wai Charles, ‘Cement and Shanghai plaster in British Hong Kong and Penang (1920s–1950s)’. In Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories (New York: Routledge, 2018), 291–98.

- Straits Times, 5 Oct 1937.