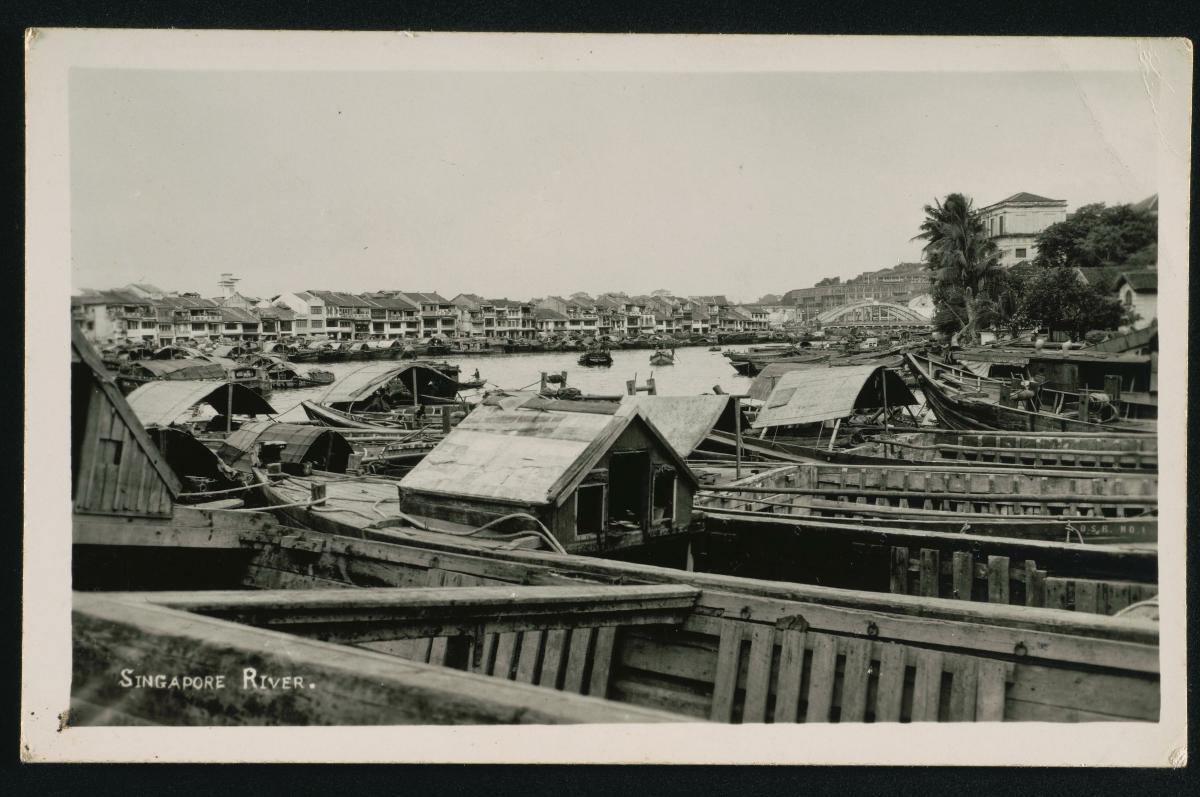

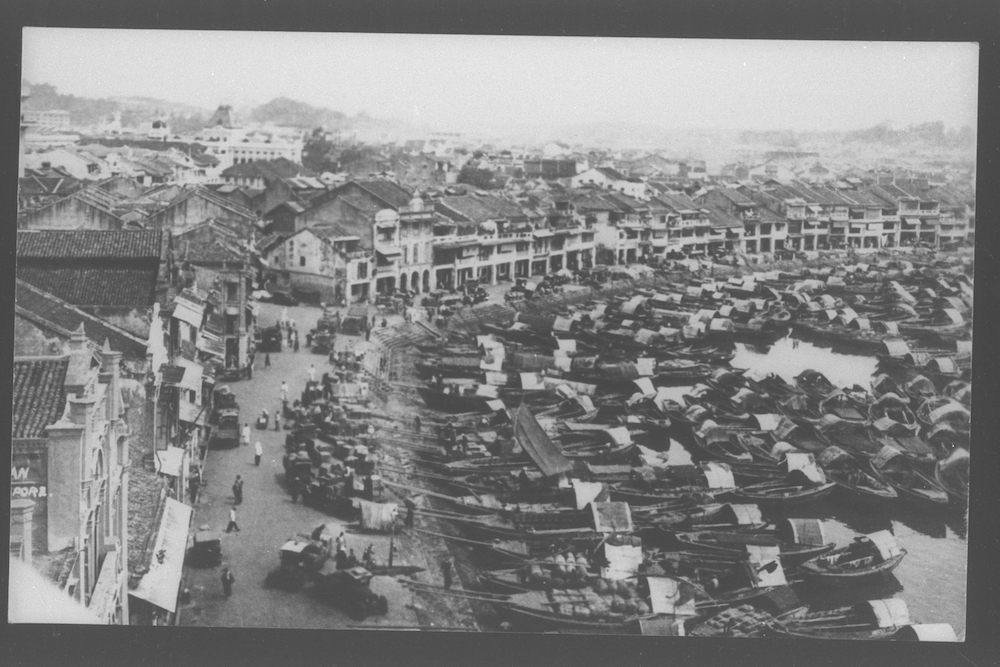

Office workers unwind at watering holes along the riverfront, while tourists snap selfies with historic monuments and sites that pepper the area – all this against a backdrop of towering skyscrapers, and river taxis that cut colourful paths across the water. This is the picturesque Singapore River we know so well.

But, it wasn’t always so. Cue the tales told in our history books of early immigrants toiling along the quayside godowns, or the mammoth clean-up campaign in the 1970s, which gave our beloved river a much needed “facelift”. And of course, there are the not too distant memories of chomping on satay at old haunts such as the Satay Club.

The Singapore River is a story about change; of how a river, as a lifeline to generations of Singaporeans over the years, contributed to the success of Singapore. Here, five objects from our National Collection bring you more stories to remember about the Singapore River.

The Singapore River Was Where…

...the legendary Singapore Stone sat...

Collection of the National Museum of Singapore.

Singapore’s founding in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles was the introduction for many to Singapore’s history.

Contrary to this, history shows that Singapore was probably already a vibrant, thriving island long before the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles. The Singapore Stone, an ancient relic that was discovered in 1819 at the mouth of the Singapore River, is an iconic marker of Singapore’s pre-1819 history.

The original stone measured 3m by 3m in its day. Legend even points to it as the boulder hurled by Badang – a folk hero known for his great strength who served the king of Singapura in 14th century Singapore - during a contest with a foreign champion.

Unfortunately, a British engineer blew up the stone in 1843 during a project to widen the river mouth, and a fragment survives today at the National Museum of Singapore.

Inscribed with an indecipherable script which some experts have claimed to be old Javanese or Sanskrit (Sir Stamford Raffles himself guessed the script to be of Indian origin), the Singapore Stone continues to baffle historians even till today.

...Singapore’s first “Bankers” traded

Collection of the National Museum of Singapore. Gift of Mr Subbiah Lakshmanan.

As a trading emporium and centre of commerce, the early days of the Singapore River saw Indian Chettiars from Tamil Nadu play the role of Singapore’s first financiers.

Arriving in the 1820s, they opened moneylending businesses in the Singapore River area, primarily along Chulia Street and Market Street.

Back then, the average Chettiar would sit cross-legged on the ground floor of a kittangi (warehouse). The pettagam, or storage chest, served as a desk on which they conducted their business.

A kittangi provided all the services of a modern bank for Singapore’s early entrepreneurs. They financed everything from rubber to real estate. They provided working capital loans, took deposits and even offered fund transfers.

With the passing of time, the descendants of Singapore’s Chettiar community went on to take up other professions.

...secret societies thrived

Collection of the National Museum of Singapore.

Secret societies were rampant along the river banks during the 19th century. Tokens were carried around by society members, for secret identification of their roles within the society hierarchy.

Early Chinese immigrants fresh off the boats in Singapore were often greeted by secret society members who would call to them in their native dialects, offering friendship, a sense of belonging and identity, and practical assistance.

For many, joining the ranks of these secret societies was the easiest way to link up with a towkay or businessman in order to get jobs pulling rickshaws or picking gambier.

The brokers of these secret societies in China would even offer to pay for their boat fare to Singapore if they could not afford it. As a result, many of the poorer immigrants would step off their ships already saddled with years’ worth of debt.

In their prime, the secret societies were immensely powerful. They collected protection money from the riverside godowns, operated gambling dens, brothels and opium houses. By 1881, nearly half of the 73,000 Chinese immigrants in Singapore were members.

The social disorder caused by the existence of these secret societies eventually forced the colonial government to intervene directly. Despite being outlawed in 1889, their presence continued to be felt well into the 20th century.

...Godowns for Gambier and other Spices were

Collection of the National Museum of Singapore. Gift of Mr G.K. Goh.

In the early 19th century, the gambier plant, a key ingredient in tanning leather, was one of Singapore’s most popular cultivation crops.

Alongside pepper, it was grown on plantations around Caldecott, Nee Soon and Sembawang. After harvest, the leaves of the plant were boiled down, squeezed and dried to make an extract that resembles burnt marshmallows.

From there, it was carted to shops along the Singapore River. Clarke Quay’s oldest building, the River House, was once a godown that stored gambier.

In the 1830s, Singapore’s gambier industry flourished, largely due to demand from British tanning businesses. Many gambier plantation owners made their fortunes from this thriving trade, including Singapore pioneer Seah Eu Chin who was also known as “Gambier King”.

...we enjoyed our favourite hawker fare

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

From 1973 to the 1990s, there was a popular hawker centre in front of the Former Empress Place Building (now the Asian Civilisations Museum).

Known as the Empress Place Food Centre, it was among the first hawker centres built during an island-wide effort to move hawkers off the streets.

Itinerant street hawkers had always plied their trade around the Singapore River, but their growing numbers, coupled with poor hygiene practices, attracted disease-spreading pests and compromised food safety.

Moving street hawkers into designated locations greatly improved the standards of food safety and hygiene. Today, hawker centres remain an indelible part of the lives of Singaporeans, and our shared food culture.

This article was developed for Singapore Heritage Festival 2017.