Text by Lucille Yap

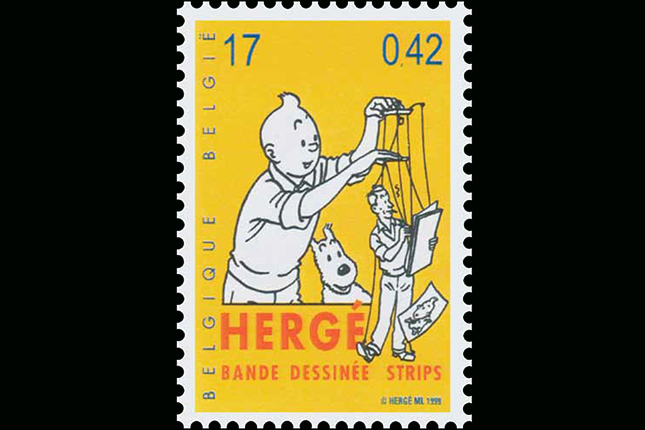

Images: Pour tous les Visuels D Hergé, © HERGÉ/MOULINSART 2012

Be Muse Volume 5 Issue 2 – Apr to Jun 2012

“TINTIN BROUGHT ME HAPPINESS. I DID MY BEST AT WHAT I WAS DOING AND IT WASN’T ALWAYS EASY. BUT I HAD A LOT OF FUN. MOREOVER... I GOT PAID FOR DOING IT...”

— Hergé, 30 December 1975 —

From 5 November 2011 to 31 May 2012, the Singapore Philatelic Museum (SPM) celebrated one of the most beloved comic characters worldwide, the boy reporter Tintin. Created by Belgian comic artist Georges Remi (1907-1983) – also known as Hergé, Tintin is a teenage journalist who began a series of exciting adventures in 1929, accompanied by his faithful dog Snowy; and later his faithful friends Captain Haddock and Professor Calculus.

Tintin’s adventures, which spanned 24 comic books, took the young reporter and Snowy to various places around the world. They ventured into India, Tibet and China in Asia; to the Congo in Africa; Arabia in the Middle East; Russia in Europe; North and South America; and even the Moon!

Shown in this exhibition were stamps from SPM’s permanent collection. Also on display were a wide range of Tintin collectibles and rarely seen original stamp artworks on loan from the Museum Voor Communicatie in the Netherlands and L’Adresse Musée de La Poste in France.

Hergé – Creator of Tintin

It is difficult to separate Hergé’s life from his work. As a child, his sketches lined the margins of his exercise books. During his teenage years, he was always with his sketchbook, and his adult life was spent eternally stuck to his drawing board.

His fictional creation was part of him, living within him and playing key roles in his life. His life influenced his creation, and his creation influenced his life.

From youth to adulthood, Hergé drew alone, with the occasional one-off collaborations. His was the work of a master craftsman, and it came from his heart and his technical expertise. But when Hergé reached the age of 40, he began to favour working within a team and set up Studios Hergé in 1950.

Hergé’s studio allowed many talented artists to flourish and develop their own work. It became an institution dedicated to the conservation and exhibition of the clear line style. Hergé was the artistic director of Tintin magazine and the managing director of Studios Hergé. But he was more of a mentor than the boss of a company.

Scout’s Honour

In 1921, the young Hergé joined the Saint-Boniface College scout group. He was given the nickname ‘Curious Fox’.

“It was with scouting that the world really began to open up in front of me. It’s the greatest memory of my youth. Being close to nature, respecting nature, resourcefulness. It was all very important to me and even if it all seems a bit old-fashioned today, I still hold dear the values we learned.” – Hergé, 1974

The budding artist was always with his sketchbook and pencil, sketching scenes of daily scout-life, landscapes from his travels and life portraits. The teenager quickly built up a good reputation for drawing such subjects.

• name: Georges Remi

• date of birth: 22 May 1907

• died: 3 March 1983 (age 75)

• nationality: Belgian

• father: Alexis Remi (1882 -1970)

• mother: Elisabeth Dufour (1882 – 1946)

• sibling: Paul Remi

• spouse: First Wife – Germaine Kieckens, secretary of Father Wallez, director of Le Vingtième Siècle. Married in 1932, separated in 1960, and divorced in 1977.

• spouse: Second Wife – Fanny Vlamynck, colourist by profession. Married in 1977.

• children: None

“As I was a boy scout, I started telling the story of a little boy scout to other little boy scouts...these were not yet real comic strips. They were more like stories with illustrations and from time to time, a shy little exclamation mark or question mark”

Hergé, 1975

The scout’s honour he so strongly embraced put him through traumatic nightmares when he was working on Tintin in Tibet. During this time, he suffered from dreams of a white monster that represented the personal conflict he had over whether he should divorce his wife of three decades to be with a 22-year-old employee.

His journey began

After completing his studies in 1925, Hergé worked in the subscriptions department of the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle (‘The Twentieth Century’).

He was talent spotted by Father Norbert Wallez, director of Le Vingtième Siècle. Noting Hergé’s abilities in lettering and illustration, Father Wallez entrusted the young man with his first graphic design assignment, such as the designing of headings, layout of newspaper columns and creation of dropped initials, tailpieces and illustrations.

Three years later, Hergé was given his first real responsibility as an illustrator when he became the editor of Le Petit Vingtième (‘The Little Twentieth ’), the children’s supplement to Le Vingtième Siècle. The first issue was published on November 1 that year.

His creations

Hergé’s first drawings appeared in 1921 in Jamais assez, a scout magazine for schools; and then in Le Boy-Scout Belge, the monthly magazine of the Belgian scouts.

From 1924 onwards, he signed his drawings as Hergé, a phonetic transcription of his initials G.R. in the reverse (pronounced as ‘Air-Zhay’ in French).

He created Totor, Patrol Leader of the May Bugs, in Boy-Scout Belge in 1926. On 10 January 1929, Tintin and Snowy made their debut in Le Petit Vingtième. In 1930, Hergé introduced Quick and Flupke, street urchins from the backstreets of Brussels who starred in short stories in Le Petit Vingtième. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was published by Editions du Petit Vingtième in the same year.

Cinema in a comic strip

Hergé’s work drew inspiration from the art of film-making. The plots, atmosphere and framing that constituted his picture stories were all heavily influenced by cinematic style. This led to his adventures, recorded in mere ink on paper, turning out to be as animated and expressive as full-length features shown in the cinema.

Hergé treated his characters as actors and he used current events and from history for his scenes. In this way, his frames and speech bubbles speak directly to us.

“I operate just like a film director. Firstly, there’s the scenario. In principle, I’m the scriptwriter as well ... It’s true that it’s very similar to the cinema. Then there’s the directing. The artist needs to be an actor and director simultaneously, and a draughtsman as well. He directs the actors. He has to feel when a character in a particular situation needs to run to the left or right or elsewhere. The artist also writes the dialogues, except in cases where there is a team with a scriptwriter and artist. In my case, I have to be everything at once.” – Hergé, 1971

Man of letters

Hergé was a prolific writer. He was as demanding of his writing as he was of his drawing and painting. He left behind approximately 40,000 letters. While the majority were about his work, there were many that touched on love, his emotions and social life.

These writings bear witness to the author’s character and taste.

This is an extract of a letter he wrote to a young girl, Anne le B., from Casablanca. She had written to him about her teenage loneliness, thinking that she was writing to Hergé’s grandfather!

“Dear Miss,

In response to your esteemed letter of 20 June, I have the honour of letting you know: that I don’t have a beard, yet if I did have one, it would not be white, but just going grey; that as I don’t have a beard, my grandchildren can’t pull it; that furthermore I’m not a true grandparent as I have neither beard nor grandchildren; that part of the reason I’m not a grandparent may be because I’m not even a father; that I limit myself to having just one wife, because that’s the Belgian custom, in contrast to your area, where the custom is to have several; that I don’t have anyone who really is the living model for Captain Haddock; that I do generally receive and see the letters I am sent; that if some malevolent force had made your hand disappear, I would have been deprived of this pleasure; and lastly that I am very keen on writing back to you, and here is the proof! Is there still anything else to write? Since you haven’t asked me anything, I don’t even have the ability to refuse you anything. Basically, you have confided that you don’t even have a rat to talk to. If I understand it correctly, you’ve promoted me to that flattering role. I am clean-shaven (‘ras’ in French) and I could also be your rat, given that our conversation would be rudimentary and short-lived. It’s not only in fairy tales that a hideous beast can be transformed into Prince Charming, in the big round eyes of a 16-year old princess.”

Tintin’s trademarks

Famous Hairstyle

His little blond quiff. This quiff was formed only on pages 7-8 of Tintin in the Land of Soviets when he jumped into a car and raced away. The sudden acceleration gave him the distinctive quiff which became synonymous with Tintin. Since then the little tuft of hair never droops.

He is always dressed in a plain yellow or white collared shirt, often with a blue sweater over, and his trademark plus-four trousers. But he traded his plus-fours for bellbottoms in Tintin and the Picaros.

Who is Tintin?

Tintin was definitely born of my unconscious desire to be perfect, to be a hero.

– Hergé.

Hergé has never confirmed who inspired him to create the Tintin character, and it may never be known who that was. But there are several claims.

Danish actor Palle Huld (1912-2010)

For decades he had claimed that his 44-day round-the-world trip, made in 1928 when he was a 15-year-old scout, was the inspiration to the appearance of Tintin a year later in Le Petit Vingtième.

French war and travel photo-journalist Robert Sexe (1890-1986)

Like Tintin, he rode a motorbike and had a best friend called René Milhoux (Tintin’s dog, Snowy, is called Milou in French). He also toured the Soviet Union, the Congo and America in the same order as Tintin in the first three comic issues.

Paul Remi, Hergé’s younger brother (1912-1986)

A military officer, Paul Remi’s likeness to the comic character prompted the nickname “Major Tintin” by his colleagues. That led him to shave off his hair and sport a ‘crew-cut’ look. Hergé reciprocated by using this new look to create the villainous character Colonel Sponz, who was featured for the first time in The Calculus Affair.

“My childhood companion and playmate was my brother, who was five years younger than me. I watched him, and he amused and fascinated me ... Undoubtedly, this explains how Tintin adopted his character, his gestures, his attitude.”

– Hergé, 1943

Last, but not least Herge&ecute; himself

The creator had claimed “Tintin, c’est moi” or “Tintin, it’s me.” ... “These are my eyes, my meaning, my lungs, my tripe! ... I believe that I am alone in being able to animate, in the sense of giving a soul.”

Know the cast

Hergé’s world was occupied by sharply defined characters. They were mostly inspired by real people who were either close to him, historical figures or celebrities at that time. Their portraits and psychological profiles had been meticulously composed, leaving nothing to chance.

>>Snowy

Tintin’s constant companion is an extraordinary white wire fox terrier. He is known as “Milou” in French. There are several stories on whom Snowy was named after. One version was that Snowy was named after Hergé’s girlfriend Marie-Louise Van Cutsem who was called “Malou”. Another candidate was René Milhoux, the best friend of French war and travel photojournalist Robert Sexe, who was himself one of many speculated inspirations of the Tintin character.

Snowy appeared right at the start, in the first drawing of the first adventure. He sticks by Tintin through good and bad times. He is faithful and courageous, saving Tintin in numerous adventures. He is known to be Tintin’s alter ego and his only confidant at the beginning.

>>Captain Archibald Haddock

The arrival of Captain Haddock does in some way replace Snowy. The Captain has always been a bit naïve, temperamental, loud, emotional and irritable, but he has a good heart and is always willing to help people who are in trouble.

His first appearance was on pages 14 and 15 of The Crab with the Golden Claws in 1941. He has been a seafaring captain of over 20 years. His ancestor was Knight François de Hadoque who commanded the frigate, the Unicorn.

Some of Captain Haddock’s distinctive features are his sailor outfit of black trousers, sailor’s hat and blue pullover with the image of an anchor; and a pipe in his mouth. His favourite exclamations are “Thundering Typhoons!” and “Blistering Barnacles!”

He is courageous but very clumsy, adding much comic relief to the stories. His main weakness is his excessive enjoyment of whisky and rum.

>>Chang Chong-Chen

This character was inspired by a young Chinese student of similar name, >张仲仁 (1907- 1998), whom Hergé met in 1934 when Chang was studying at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.

The extremely beneficial relationship inspired both Hergé’s professional and spiritual life. This marked a turning point in Hergé’s career, and was central to the creation of The Blue Lotus in 1935. Twenty-four years later Hergé celebrated his friendship with Chang again in Tintin in Tibet.

“I think that Chang was, without knowing it, one of the artists who had the most influence on me. He was a young Chinese student whom I had first met at the time when he helped me to create The Blue Lotus, and it was he who made me aware of the absolute necessity of being well informed about a country and of constructing a narrative.”

– Hergé, 29 April 1977

Chang returned to China after he completed his studies in 1937. He became the Principal of the Shanghai Fine Arts Academy and was a celebrated sculptor.

The two good friends lost contact when World War Two broke out. The Japanese occupation of China during the war, coupled with the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), separated them for almost three decades. Hergé, however, never gave up looking for his friend. His long quest finally paid off in 1975, and they kept in contact through touching letters. It was not for another six years before Chang and Hergé had an emotional reunion in Brussels in 1981.

>>Thompson & Thomson

These two clumsy policemen first appeared in Cigars of the Pharaoh in 1932. They were then known as X33 and X33A. Their names were revealed only in King Ottokar’s Sceptre in 1939.

The only way to distinguish between the two is from the trim of their moustaches. Thompson’s is neatly trimmed, whilst Thomson’s has a distinctive twirl at the ends.

Both Thompson and Thomson are not very intelligent, and are incredibly clumsy and confused. They are hence full of blunders, misunderstandings, and always in trouble. One possible inspiration for the characters was Hergé‘s father, Alexis Remi, and Alexis’ twin brother, Léon. They were identical twins; both had moustaches, were dressed alike, wore boater or bowler hats, and held walking canes or umbrellas. Thompson and Thomson, however, are not twins.

Hergé could also have been inspired by movies of that time, namely the films of Charlie Chaplin, as well as the comedic duo Laurel and Hardy who shared similarities in characteristics with Thompson and Thomson.

Professor Cuthbert Calculus

He is an absolutely deaf and absent-minded inventor whose French name is Tryphon Tournesol. “Tryphon” is the name of Hergé’s carpenter and “Tournesol” means sunflower. He was actually modelled after a real person.

“Physically, Calculus and his submarine were based on Professor Auguste Piccard [1884-1962] and his bathyscaphe. He was a scaled down version of Piccard, who was much too tall. Piccard had a very long neck. I would occasionally bump into him in the street and he struck me as the incarnation of a typical scientist. I made Calculus a mini-Piccard, because otherwise I would have needed to enlarge the frames.”

– Hergé

Calculus’s deafness was modelled after Paul Eydt, the lawyer at Le Petit Vingtième. His deafness was a source of jokes amongst the editorial team.

>>Roberto Rastapopoulos

A dangerous Greek billionaire with the worst morals and taste in clothing, Rastapopoulos is a master of evil and the sworn enemy of Tintin.

His first appearance was in Tintin in America in 1932. He crossed paths with Tintin again in Cigars of the Pharaoh in 1934, The Blue Lotus in 1935, The Red Sea Sharks in 1958, and finally in Flight 714 in 1967.

He was modelled after the Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis (1906-1975), who made a fortune constructing super tankers and became legendary for his wealth and display of it.

>>Dr. J.W. Müller

Violent and dangerous, enterprising and unscrupulous, and thoroughly evil, Dr Müller’s personality was based on Dr Georg Bell, a secret agent cum forger and a Nazi troublemaker of Scottish descent.

Physically, Dr Müller was based on the British actor Charles Laughton who starred in the film The Island of Doctor Moreau (1933). Laughton played the role of a mad genius, a pioneer of genetic modification and super surgeon, joining animals and humans together to create monstrous hybrids.

Dr Müller made his first appearance in The Black Island in 1938 as an outlaw and a master of disguise who often assumed multiple identities.

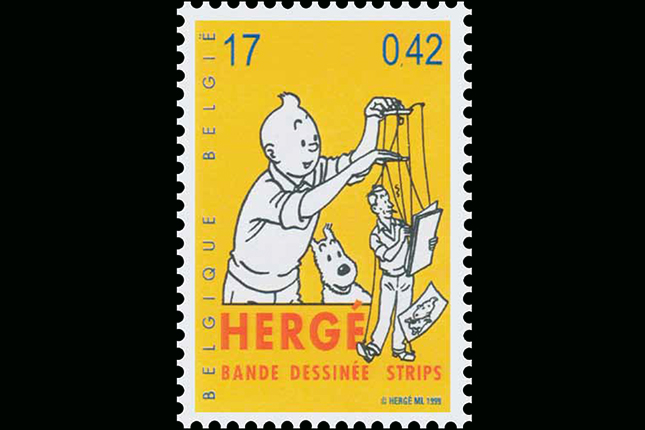

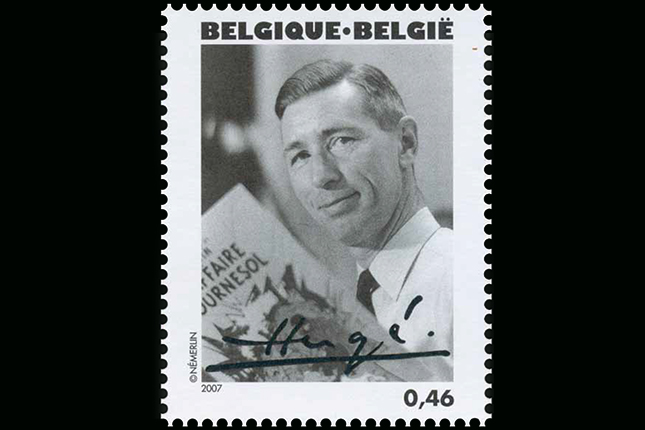

Celebrating Tintin through stamps

The Adventures of Tintin in 24 Albums

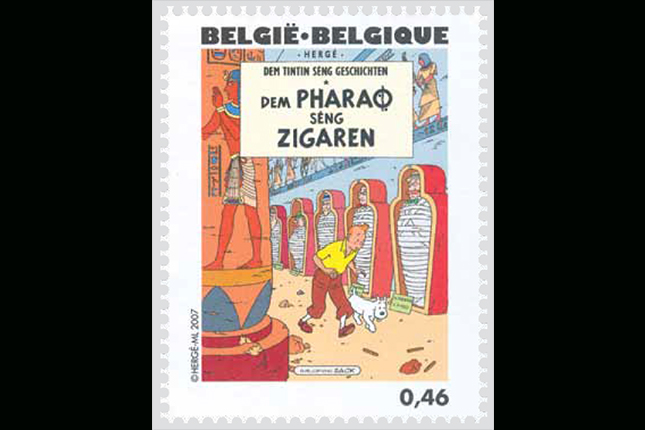

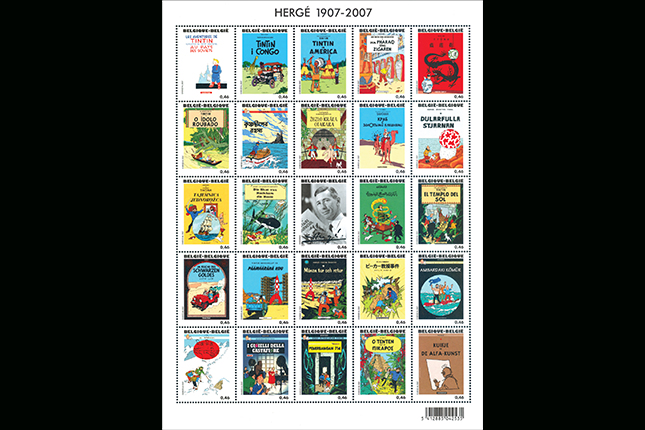

This 2007 stamp collection issued by the Belgium Post features the covers of all 24 titles of the Tintin comic book series, together with a portrait of Hergé.

Albums 2 to 9, which were originally in black and white, were republished in colour and in a fixed 62-page format between 1943 and 1947, as well as in 1955. Album 10 was the first to be published in colour right from the beginning. Albums 16 to 23 (and the revised editions of Albums 4, 7 and 15) were published with Studios Hergé.

A shortage of paper during World War Two had restricted the comics to 62 pages instead of the 100-130 pages allowed before the war.

The Double-Adventure Sequels

The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure were Hergé’s first attempt at dividing Tintin’s adventures into two parts.

The double-adventure was such a successful formula that Hergé repeated it in four other books. The second double-bill, which came right after Red Rackham’s Treasure, spanned The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun. The third double-adventure was told in Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon.

Hergé had attempted to create a sequel earlier in 1934 when he embarked on Tintin in the East in Le Petit Vingtième. But the resulting work, The Blue Lotus, was more of a companion volume rather than a straight sequel to the preceding book, Cigars of the Pharaoh.

Tintin on the Moon

Hergé’s world was filled with science and technology. He was an inquisitive artist who sought out and interviewed numerous scientific experts. The process reached its peak in Tintin’s adventure to the Moon.

Hergé had the ability to weave complicated scientific subject matters into truly remarkable stories. He drew inspiration from the space race between America and the Soviet Union in the 1950s, keeping close tabs on new developments in rocket science.

To ensure accuracy in his work, Hergé made a scale model of the Moon rocket to be featured in Destination Moon, and brought it to Paris for the approval of Professor Alexandre Ananoff, author of L’astronautique. The model could be dismantled to reveal each inner section clearly. Upon his return to Brussels, Hergé asked his assistants to draw the iconic red rocket based on his model.

“I wanted Bob De Moor [one of Hergé’s assistants] ... to know exactly whichever part of the space vehicle the characters were to be found in. It was essential that each detail was in place, that everything was perfectly exact: the venture was too dangerous for me to be involved without guarantee.”

– Hergé

Hergé was way ahead of his time. He put Tintin on the Moon in 1953, four years ahead of the Soviet Union which launched the first, unmanned, Sputnik rocket on 4 October 1957. And it was not until two decades later on 20 July 1969 that Neil Armstrong from the United States’ Apollo XI mission finally landed and set foot on the Moon. As a fitting outcome to this creative undertaking, Tintin became, in the eyes of many, the first man to walk on the Moon!

“This is it! ... I’ve walked a few steps! ... For the first time in history of mankind there is an Explorer on the Moon!” – Tintin declared in 1953, 16 years before Neil Armstrong’ declaration of “ one small step for man, one Gian leap for mankind”

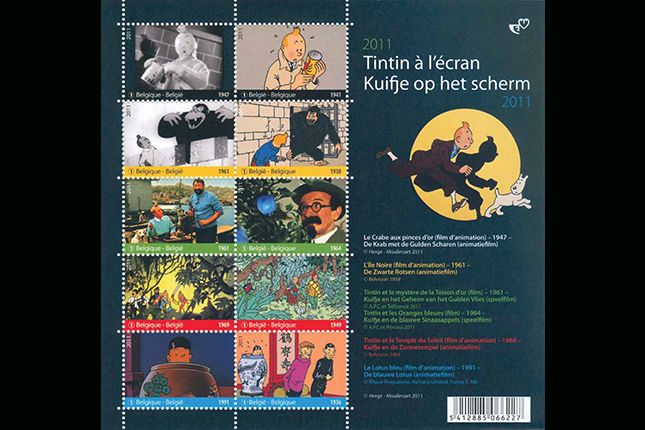

Tintin comics have been made into movies since 1960, when Tintin first appeared on the big screen in Tintin and the Golden Fleece. This was followed by Tintin and the Blue Oranges in 1964.

In 1969, Belvision Studios in Brussels produced a feature-length animated cartoon based on the book Prisoners of the Sun. In 1976, Moi, Tintin, a full-length documentary about Tintin and his creator, hit the screens.

In October 2011, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, made its debut as a computer animated 3D movie. Directed by Steven Spielberg, the movie script was based on three of the comic stories: The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure. A new set of stamps was issued by bpost (Belgium Post) on 27 August 2011 to mark this special occasion.

Lucille Yap is Senior Curator, Singapore Philatelic Museum.