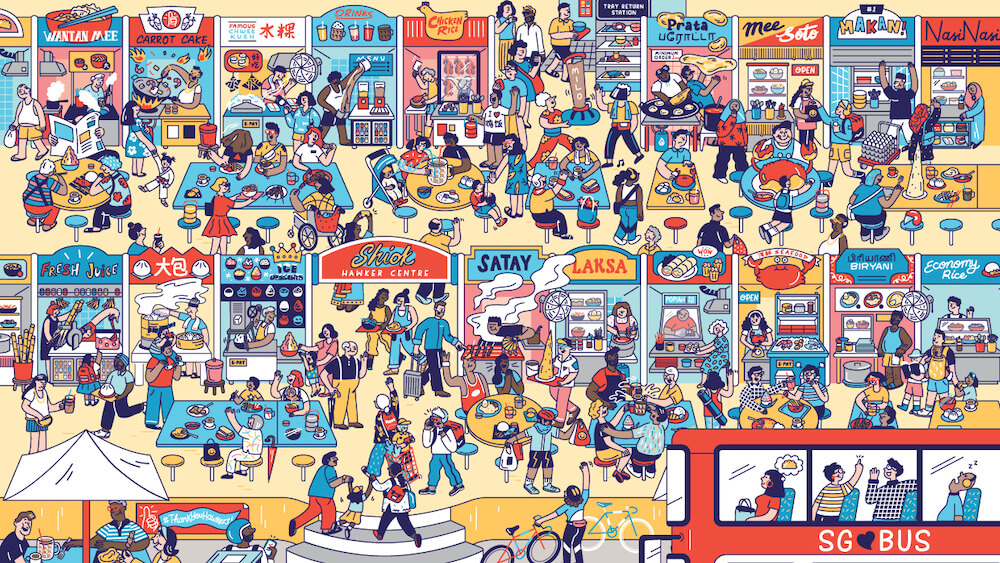

Ask any Singaporean what the most important part of the local heritage is, and chances are, the answer would be Hawker Culture. From the world-famous chicken rice to the late night roti prata, the crowd-favourite laksa to the comforting flavours of nasi lemak, Singapore’s hawkers have been feeding generations of people from all walks of life. Hawker food plays a much greater role than just filling our bellies – it is a legacy that unites all Singaporeans.

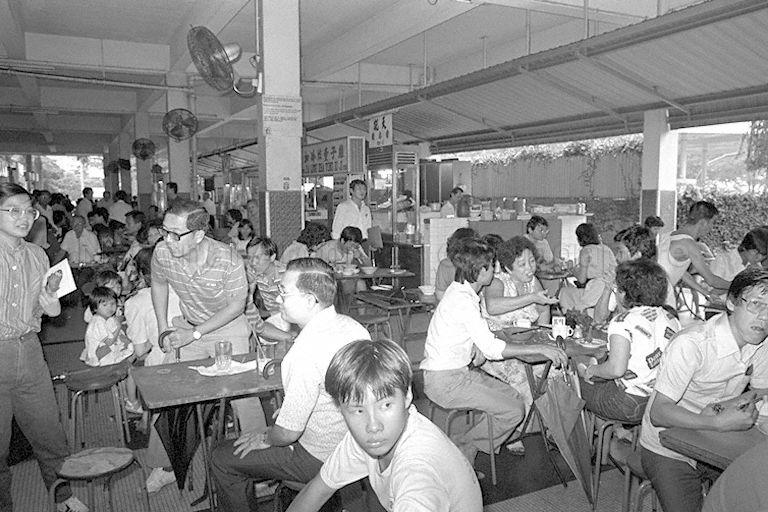

From Boon Lay to Maxwell and to Bedok, hawker centres have become the nation’s community dining rooms, where the office worker takes his usual morning breakfast perhaps in a hurry, while the retired senior digs into a bowl of noodles at his own leisure. Neighbours meet up regularly to catch up on news and gossip, parents dart from stall to stall to bring home their children’s favourite dishes, and grandparents reminisce about the good old days over a cup of freshly brewed coffee. It all happens right here.

So where did our Hawker Culture come from? What does it represent for Singaporeans? To really understand the Singaporeans’ love story with hawker food, we will have to journey right to the beginning, when our ancestors brought the very first hawker dishes from their homeland.

History of Hawker Culture

1800s – The Origins

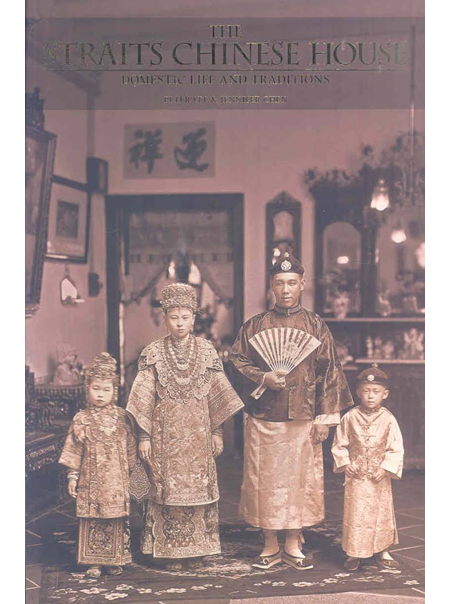

Singapore in the 1800s was a thriving port city which attracted migrants from China, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and other lands, seeking a better life. They were hard labourers, merchants, clerks, and cooks who brought with them the comfort food they grew up with. They adapted these dishes to ingredients that were easily available here, and cooked them using local techniques, eventually creating a recognisable Singapore flavour.

Many immigrants saw street hawking as a good way to earn a living, as it required little capital. These early pioneers started to ply the streets, serving the dishes that they were most familiar with. The streets were bustling with activity, colours, aromas, and flavours. Chinese hawkers would carry their mobile kitchens around, balanced on a bamboo pole along with their ingredients and utensils, so they could serve up piping hot meals on the go. Malay hawkers typically sold fruits and flame grilled meat sticks, a dish that we would come to know as satay. Indian hawkers added colourful sweets, cakes, and jellies to the street scene. One could even see a hawker walking his cow or goat on the street, ready to “dispense” fresh milk whenever a customer demanded.

With just three cents, anyone could afford a sumptuous meal of three to four dishes, served up at a moment’s notice. On the same street, one could easily savour the flavours from different parts of Asia, catered to local tastes. This vibrant beginning marked the first chapters of Singapore’s hawker story.

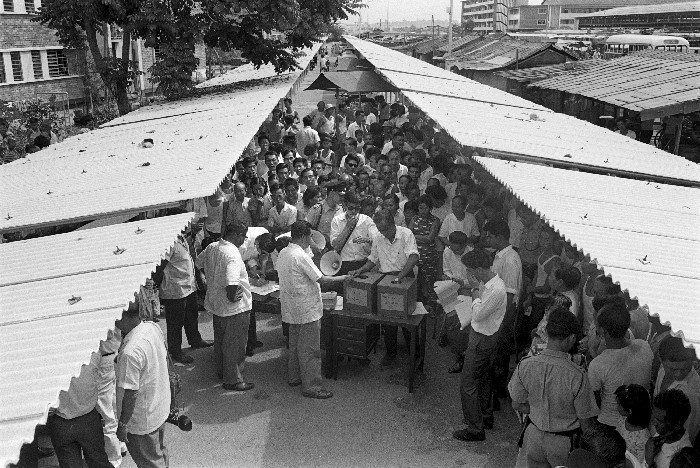

Up to 1960s – A need for regulation

After the Second World War, many who were unemployed turned to hawking as a profession, and that was when the street hawker scene became a thriving world of possibilities.

However, not everyone shared the optimistic view of Singapore’s street hawker scene. In 1950, Governor F. Gimson set up the Hawkers Inquiry Commission and in the Hawkers Inquiry Report, it was stated that “There is undeniably a disposition among officials ... to regard the hawkers as primarily a public nuisance to be removed from the streets.”

The hawkers in Singapore during that time usually did not have easy access to water. This made it difficult to keep their utensils clean and prevent contamination by flies and rats. Without a properly assigned disposal area, hawkers often left piles of refuse on the streets, posing a threat to public health and hygiene. Many who were selling cold drinks, cut fruits, and ice cream used water and ice that might be easily contaminated, potentially causing outbreaks of cholera and typhoid.

Another issue the government faced was the challenge in street cleaning as the entire physical space where the hawkers plied their trade was viewed as a disorderly obstruction to traffic and city planning. As such, the colonial government started looking for ways to regulate the hawkers and relocate them.

Late 1960s to 1980s – The first hawker centres

After Singapore’s independence in 1965, along with the move to turn Singapore into the region’s business hub, the work of licensing hawkers and relocating them into more organised spaces picked up momentum. In 1968 and 1969, the government conducted an islandwide registration of street hawkers, issuing temporary licenses and moving them into back lanes, car parks, and vacant plots of land.

Despite this move, illegal hawking remained rampant. In 1974, the Hawker’s Department Special Squad was formed to handle the situation. Public Health Inspectors, who were responsible for keeping illegal hawkers off the streets, were given handsets similar to those used by the police and could use them to relay information and seek backup assistance while CISCO officers escorted them on the ground. These new measures proved especially effective against the illegal pasar malam (night markets) that sprung up across the city.

Enforcement was not all bad news. From 1971 to 1986, the government sought to relocate up to 18,000 hawkers to markets and hawker centres with proper amenities, so hawkers could have a safe and hygienic place to work without having to run from the inspectors.

The Housing Development Board (HDB) was responsible for the meticulous planning of every hawker centre to make sure that they were in well-populated areas. Each hawker centre was built within walking distance for most residents of the HDB estate, or a short bus ride away, while not being too close to one another. Chomp Chomp Food Centre, Block 51 Old Airport Road, and Tiong Bahru Market were among the first hawker centres to serve up mouth-watering Singaporean delicacies in this exciting new era of the hawker story.

1980s to present – Building a legacy

The five-year span between 1974 to 1979 saw 54 hawker centres built to serve residents and workers across the nation. Different architectural and design themes gave each hawker centre their unique touch. Newton Hawker Centre, for example, was built in 1971 with the idea of having “hawker stalls in a garden setting” with trees for shade, hedges and shrubs alongside a car park and a public toilet. The last food centre to be erected during this phase was Block 505 Market and Food Centre at Jurong West Street 52, in 1986.

Today, more than 110 hawker centres are located across Singapore, and there are plans to construct even more to better cater to our population (data extracted from the website of the National Environment Agency).

“Hawker centres represent the culinary soul of Singapore, where everyone regardless of race and social background gathers for their daily meals. I grew up having meals at hawker centres and hope that my daughter gets to enjoy the same culinary experience as I do.” Hugo Bart, frequent patron at hawker centres

Even our hawkers have chosen to continue their family’s legacy by carrying on the trade that their parents or grandparents had started. More than half of today’s hawkers are second and third generation hawkers, most of them specialising in a particular dish, refining the recipes that have been passed down to them, and sometimes adding adventurous twists to their flavours.

Haron Satay & Chicken Wing has come a long way from being razed by a fire in 2013 to the passing of their founder in 2016. Regulars nicknamed the satay as bakar-ed satay Haron as a tribute to the late Mr Haron Abu Bakar who founded the Satay in 1978. (2018. Photo courtesy of National Heritage Board.)

“My customers are like my close friends; I can even say some are like extended family. As a hawker, I don’t just sell the food, I share the culture and heritage to my fellow Singaporeans.” Mdm Muthuletchmi, Hawker at Ghim Moh Market & Food Centre

Gearing up for the Future

The Hawker Centres Upgrading Program (HUP) was launched in February 2001 to improve the dining experience at hawker centres, both for the hardworking hawkers and the patrons. Upgraded hawker centres enjoy re-tiling, new tables and seats, replacement of utility services, rewiring, improvement to the ventilation, bin centres and toilets, re-roofing where necessary, and provision of exhaust flue systems. Some centres even go through a complete reconfiguration or rebuilding. In addition to central freezer areas, central wash areas are also set up for sorting out used crockery. While the space is not air-conditioned to keep operating costs down and to preserve the traditional atmosphere and charm of hawker centres, barrier-free access has been prioritised to facilitate the movement of patrons in wheelchairs.

In 2019, the government announced that 13 new hawker centres will be built by the year 2027. This new chapter would inject new energy into Singapore’s Hawker Culture, combined with the latest technologies in automation and sustainability, while preserving the heritage and authenticity of our hawker centres. The new hawker centre in Bukit Panjang, for example, is built with a trellis at its roof garden to allow for the installation of solar panels. Other sustainable features include a pneumatic waste conveyance system that will transport waste automatically to a central station through a network of pipes, so that cleaning would be more efficient and effective.

Honouring our Hawker Culture

The story of our Hawker Culture would never have been written if not for the passion of hawkers, and the support of community groups, the government, and food-loving Singaporeans. The rich culinary offerings of our hawker centres represent the Chinese, Malay, Indian, and other communities that call this country home. In recent years, international cuisine has also made its way into the heartlanders’ bellies. Patrons today can enjoy fish and chips, Japanese udon sets, Hong Kong dim sum, and even Korean kimchi at their favourite hawker centres.

“Our family is always looking into new ways to excite our customers without losing the touch of our traditional roots. It’s not just food; we are serving a legacy.” Afiq Rezza bin Norrezat, Hawker at Ang Mo Kio Market & Food Centre

Safeguarding Singapore’s Hawker Culture

There are four pillars to the safeguarding of Singapore’s Hawker Culture – Transmission, Research and Documentation, Support and Promotion. These are demonstrated through the collaborative efforts among government agencies, hawkers, training institutions, community organisations, academia, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and individuals.

Transmission

Hawkers are encouraged to pass down their culinary practices to apprentices or family members. This is demonstrated through initiatives such as the Hawkers’ Development Programme, introduced by the National Environment Agency and Skills Future Singapore to teach aspiring hawkers about the culinary secrets of experienced hawkers, and to provide apprenticeships, to ensure that our hawker favourites will continue to be served for generations to come.

Research and documentation

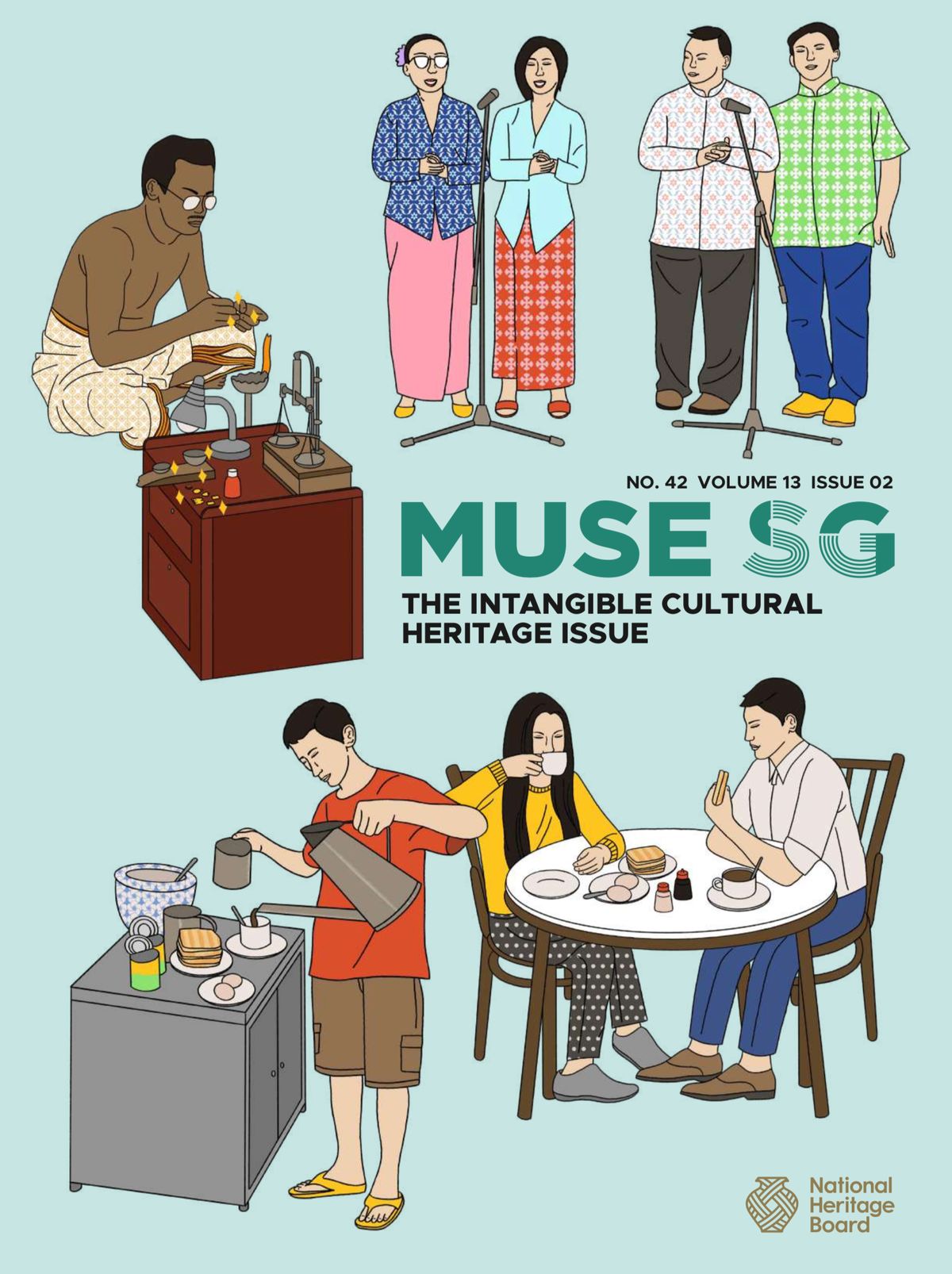

Local food advocates and community organisations have been actively documenting the country’s rich hawker heritage and recipes of local delights. This culture has even piqued the interests of academics and experts. This rich library of publications, editorials, and multimedia materials continue to grow, providing the public with a comprehensive resource pool to further enrich their love for local food.

Support

Organisations such as the Federation of Merchants’ Associations, Singapore (FMAS), as well as other hawkers’ associations and representatives, work closely with the government to provide support and additional resources for our hawkers. The National Environmental Agency (NEA) has also set up an Incubation Stall Programme to encourage aspiring hawkers to set up their stalls with a lower start-up cost and pre-fitted basic equipment. Together, these organisations have also organised the Hawkers’ Seminar to encourage hawkers to come together to exchange ideas and strengthen the survivability of the culture.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, support schemes, grants and courses on digital solutions were offered to help hawkers tide through the difficult period.

Promotion

Heritage and food enthusiasts, as well as museums and other organisations have launched exhibitions and campaigns to help promote Singapore’s Hawker Culture. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as Slow Food Singapore, have also been organising different workshops and programmes to educate students and the wider community about our food heritage, while private entities like Eat.Shop.Play have tapped on digital and social media to promote hawker stalls in Singapore.

UNESCO Inscription of Hawker Culture in Singapore

Our Hawker Culture resonates strongly with locals across all ethnicities and social strata, and it is also something that Singaporeans are proud to showcase on the international stage.

On 16 December 2020, Hawker Culture in Singapore was successfully inscribed as Singapore’s first element on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, with the unanimous support of the Intergovernmental Committee for the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage. The inscription reflected our Hawker Culture’s significance in Singaporeans’ multicultural identity as a people, and as a nation, and affirms our commitment to safeguard it for future generations.

From hawker plates to global palates

So, what does it mean for Singaporeans for our hawker culture to be inscribed as the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity? For the nation, it confirms our international standing as a culinary destination on the world map. For our hawkers, this is a recognition that their years of hard work have shaped Singapore’s culture for entire generations. For our food lovers, it is a testament of our passionate late-night visits to Chomp Chomp and our weekend trips across the island just to enjoy a bowl of laksa – a culinary love story that is forever written in history.

For generations to come, every Singaporean will continue to enjoy the traditional flavours from their heritage and various ethnic groups. Each bowl of soup, each plate of rice, and each cup of coffee – made with two centuries of passion and pride through the hard work and creativity of hawkers who adapted to the changing times and needs of communities.