Traditional Malay Music

The musical genres in traditional Malay music include asli (‘original’, ‘traditional’), ronggeng, inang and joget (music which typically accompanying social dances), dondang sayang (songs of affection), keroncong (a type of folk music), zapin (music accompanying the zapin dance) and ghazal (typically tied to themes of romance sung in poetic quatrains). Practitioners have shared that characteristics of traditional Malay music from these various genres include the use of grenek-grenek, which are trill signatures in compositions, and the use of cengkok which is the use of extended melismatic notes (singing a single syllable text and carrying it through multiple notes). The lyrics of traditional Malay music are usually set in Malay poetic forms – namely, the pantun, gurindam and syair, which lends a distinct Malay form of cultural expression.

Malay musical forms are constantly under reinvention and assimilation, especially with regards to stylistic experimentation and compositional variety. Various cultures, including Hindustani, Arabic, Chinese, Javanese and Portuguese music have been fused into Malay music forms. Due to the particular context and community for traditional music consumption in Singapore, traditional Malay music ensembles here often do not specialise in any one particular genre or style and instead, embrace various genres.

Geographic Location

Traditional Malay music forms are present in Southeast Asia, including Malaysia and Indonesia, each with their respective regional variations.

In Singapore, traditional Malay musical ensembles perform at various platforms such as community events, weddings and festivals, as well as in concert halls.

Cultural groups in schools also take part in public performances as well as in island-wide competitions.

Communities Involved

Traditional Malay music is enjoyed by the Malay community and the wider community in Singapore.

Examples of traditional Malay music groups in Singapore include the Orkestra Melayu Singapore (OMS), an ensemble that was formed by the People’s Association to promote and preserve traditional asli music in Singapore. Their youth wing called OMS Belia, was formed in 2004 to involve young Malay musicians who are passionate about traditional Malay music. Orkes Sri Temasek and Orkes Sri Mahligai formed in 2011 and 2002 respectively, are also well established orchestras in Singapore.

Traditional Malay music ensembles have close relationships with local Malay dance troupes in Singapore, as they often provide the musical accompaniment for dance pieces.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

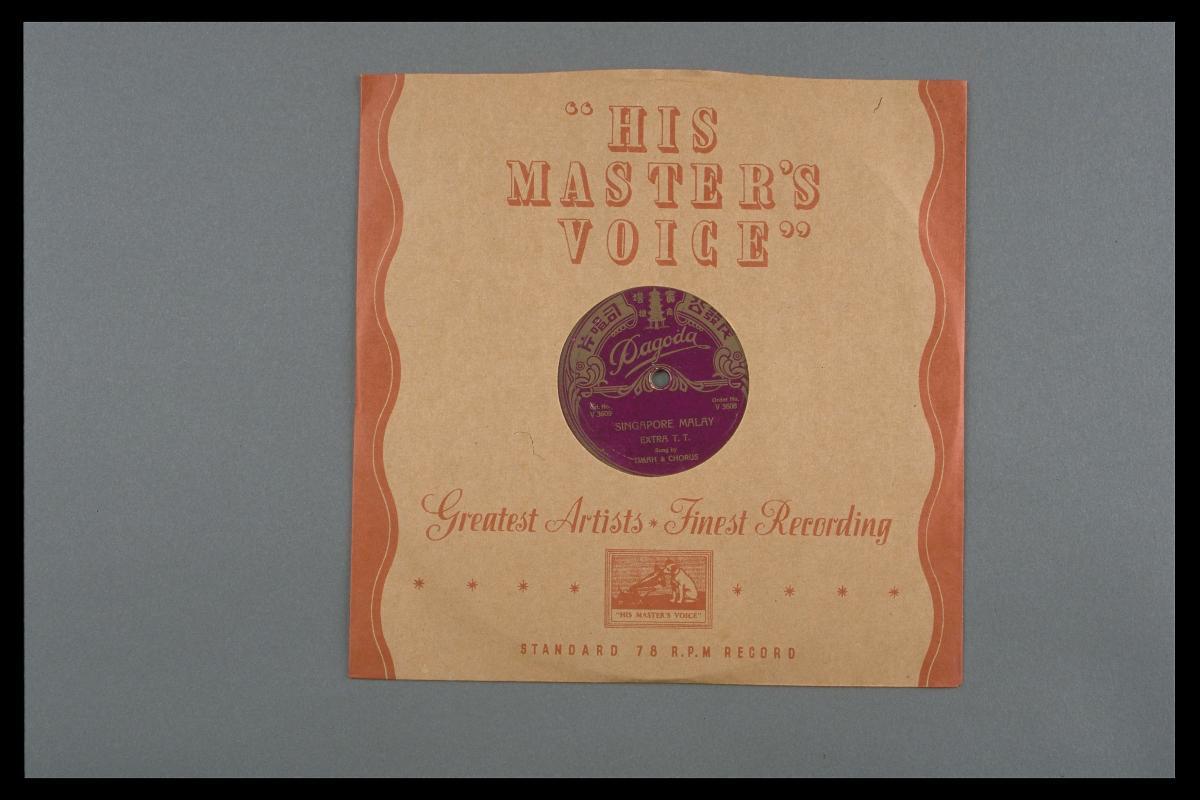

Traditional Malay music can be traced back to the 19th century, where historic texts mention nobat (the royal orchestra that performs during coronation).

The asli genre is the basic idiom of traditional Malay music. Asli is often referred to as old traditional or semi-traditional music style or performance. It is said to be derived from the dondang sayang genre, with fixed lyrics. However, the performance is delivered in a highly improvised manner through the cengkok (melismatic notes) and subsequently the grenek (the ornamented style). In asli laggam, the melody is sung in unison with the violin throughout the performance of a song. In this genre of music, the violin is the most important instrument and is accompanied by an accordion or harmonium, knobbed gong, gendang (two-headed drum), rebana ubi (the largest drum in the rebana family of drums), seruling (bamboo flute) and bass guitar.

The ronggeng, inang and joget are genres of music that traditionally accompany a social dance and the singing of pantun. It is performed typically with the violin, accordion, rebana (drum) and brass knobbed gong. Although these three genres have differing rhythmic and melodic patterns, the inang and joget are usually played at a faster tempo.

The dondang sayang (songs of affection) genre is sung by two or more singers in pantun. The singers pit their wits against one another through cajoling or teasing repartee, where the singers sing in response to one another. This is sometimes improvised. The lyrics often follow the themes of the various dimensions of social life, such as romance, advice or wisdom. The instruments that accompany the vocals are the violin, rebana (drum), accordion or harmonium, a single knobbed brass gong and tambourines.

The keroncong is believed to have Portuguese and Indonesian origins. The common instruments associated with it are the ukulele and string guitar, seruling (bamboo flute) or the Western flute, banjo or bass banjo, cello or violin, western double bass, rebana ubi, and the accordion.

The ghazal genre is sung in poetic quatrains and is usually linked to the themes of romance. It is commonly associated with Johor, Malaysia, and is believed to have origins in the Middle East. The vocalist will first start singing a line, before the ensemble plays the melody. The harmonium, gambus (short-necked lute), violin, guitar, tabla (pair of Indian drums), tambourines and maracas are the instruments commonly used in this genre.

The zapin is also associated with Johor, with roots in the Middle East. Instruments used for this genre include the gambus (short-necked lute) or oud (lute), marwas (two-sided hand drum), violin, accordion, rebana ubi, seruling (reed flute) and tenawak (gong). Zapin begins with the improvisation of the oud or gambus and closes with a contrasting rhythmic pattern called kopak.

Various experimental and fusion-jazz ensembles that draw inspiration from these genres have been formed in the last few by young musicians conversant in both Malay traditional music styles and Western compositional methods and techniques. One example is Nusantara Arts, a collective ensemble of musicians who assimilate influences and instruments of the Malay Archipelago (such as the keroncong, cello, serunai and accordion) into jazz and acoustic folk styles. Another group, the Bhumi Collective, produces works that synthesises the spirit of traditional Malay music and dance together with experimental theatre.

Experience of a Practitioner

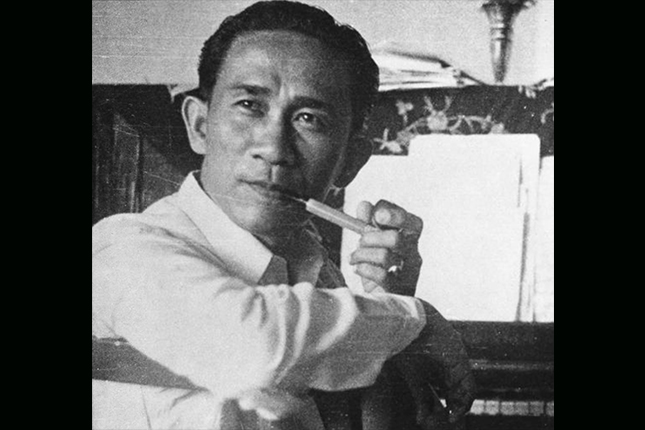

Mr Ariffin bin Abdullah is the band leader of Sri Mahligai Orkes Tradisional Melayu. In 2000, he helped set up the traditional Malay orchestra and pursued Malay traditional music full-time. Prior to this, he was in a band called Kemoening, and played Malay pop hits and 80s English hits. Mr Abdullah taught himself how to play the gambus (lute) in the early 1990s, and this kick-started his interests in developing a traditional Malay ensemble. He did so to counter what he perceived as a decline in the knowledge of traditional Malay music, as the Malay media was saturated with western-influenced rock and pop songs. The respondent previously encountered Malay traditional music in Malay film songs, and this made the transition between playing a new instrument and changing genres comfortable for him. He was subsequently given full control of Sri Mahligai Orkes Tradisional Melayu upon the mentorship and encouragement of his mentor, Mr Jaffar Sidek.

Present Status

Mr Ariff believes that the future of traditional Malay music in Singapore is healthy as long as the local community continues to support it. He believes that the documentation of songs, recording and writing about Malay music should be encouraged. Lectures and masterclass on composing as well as instructions on the use of the traditional Malay instruments should also be commonplace. He hopes that the continuation of music festivals, community showcases, workshops and school demonstrations will further encourage the appreciation of traditional Malay music by local and overseas communities.

References

Reference No.: ICH-071

Date of Inclusion: October 2019

References

Barendregt, B. Sonic Modernities in the Malay World: A History of Popular Music, Social Distinction and Novel Lifestyles (1930s–2000s). Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Barnard, T. P., & Maier, H. M. “Melayu, Malay, Maleis: journeys through the identity of a collection” In Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity Across Boundaries. Singapore: NUS Press, 2004.

Carstens, S. “Dancing lions and disappearing history: The national culture debates and Chinese Malaysian culture”, Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 23: 11–63, 1999.

Chan, A. W. Y. “Composing race and nation: Intercultural music and postcolonial identities in Malaysia and Singapore”. PhD dissertation, Musicology. Australian National University, 2013.

Chopyak, J. D. “Music in Modern Malaysia: a survey of the music affecting the development of Malaysian popular music”, Asian Music 18(1): 111–138, 1986.

Dairinathan, E & Phan, M.Y. A Narrative History of Music in Singapore: 1819 to the Present. Technical report submitted to the National Arts Council, Singapore, 2002. https://repository.nie.edu.sg/bitstream/10497/4539/1/A_narrative_history_of_music_in_Singapore_1819_to_the_present_a.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2019.

Kahn, J. S. Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay world. Singapore: NUS Press, 2016.

Lockard, C. A. Dance of Life: Popular Music and Politics in Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998.

Matusky, P., & Tan, S.B. The Music of Malaysia: The Classical, Folk and Syncretic Traditions. Hampshire: Ashgate, 2004.

Matusky, P., & Tan, S.B. The Music of Malaysia: The Classical, Folk and Syncretic Traditions. London: Routledge, 2017.

Meddegoda, Chinthaka Prageeth “Adaptation of the harmonium in Malaysia: Indian or British heritage?” In Gisa Jähnichen (ed.), Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis III (New Series), Münster: MV-Wissenschaft, pp. 219–238, 2013.

Meddegoda, C.P. & Jähnichen, G. Hindustani Traces in Malay Ghazal: ‘A Song so old yet still famous’. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Tan S.B. Bangsawan: A Social and Stylistic History of Popular Malay Opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Tan S.B, “From folk to national popular music: Recreating ronggeng in Malaysia”, Journal of Musicological Research 24(3-4): 287–307, 2005.

Weintraub, A. “Music and Malayness: Orkes Melayu in Indonesia, 1950–1965” Archipel 79(1): 57–78, 2010.

Weintraub, A. N. “Review of Melayu: The Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Malayness”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 44(3): 526–543, 2013.

Weintraub, A. N. “Pop Goes Melayu: Melayu Popular Music in Indonesia, 1968–1975” In Barendregt, B. (ed.) Sonic Modernities in the Malay World: History of Popular Music, Social Distinctions and Lifestyles (1930s-2000), pp. 165–186, 2014.