Thaipusam

Thaipusam is a Hindu festival held on the full-moon day in the month of Thai in the Tamil calendar (January-February). It is dedicated to Lord Murugan, an important god for Tamils who form the majority of ethnic Indians in Singapore.

During the festival, devotees give thanks to Lord Murugan who symbolises the traits of bravery, power and virtue. The festival commemorates the occasion where Lord Murugan overcame evil forces with a vel (spear) and this explains why the vel is included in festival celebrations and procession.

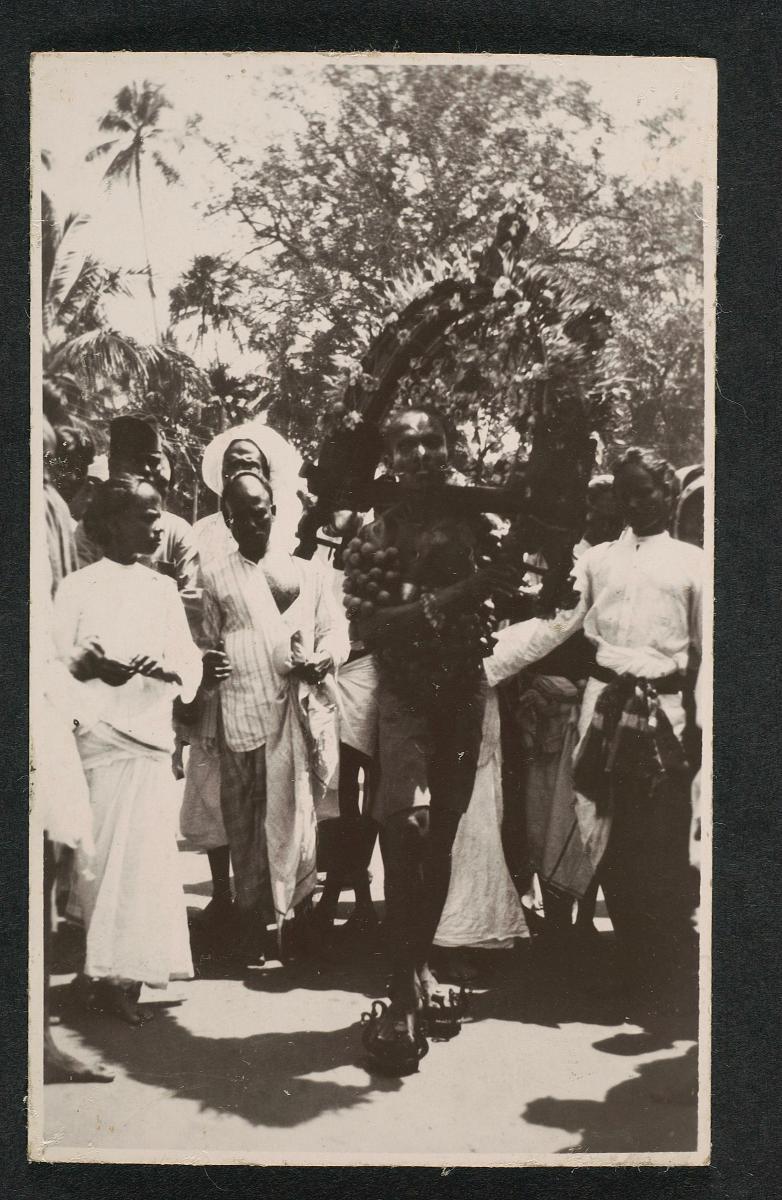

Some of the practices associated with Thaipusam include a procession where devotees carry pal kudam (milk pots) as offerings, while others carry kavadis. Kavadis are made of wood or steel arched frames that can be adorned with pictures of deities, peacock feathers and small pots of milk. They are usually fixed onto the bearers’ bodies through piercings, rods and chains.

Geographic Location

Thaipusam is celebrated wherever there is a significant Tamil community. This would include countries like India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritius, Fiji, some Caribbean islands and even the United States of America. However, some have noted that the practice of carrying body-piercing kavadi is more common among the Tamil diaspora than in India. The festival in Singapore is one of the largest in South-east Asia and includes kavadi-bearing devotees walking barefoot in the annual procession from the Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple in Serangoon Road to the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple in Tank Road.

Communities Involved

Thaipusam and its associated practices play a big role in the life of many Tamil Hindu devotees in Singapore. The festival requires extensive organisation to cater to the tens of thousands who take part in the annual processions. Great care is taken to support the kavadi bearers, including providing food and drinks, medical support, and helping devotees put on their kavadi. People from other ethnic groups have also participated in kavadi processions, even though they may not take part in the other rituals. In addition, non-Hindu Singaporeans and tourists also enjoy the festival by observing the processions and rituals of Thaipusam from the side.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

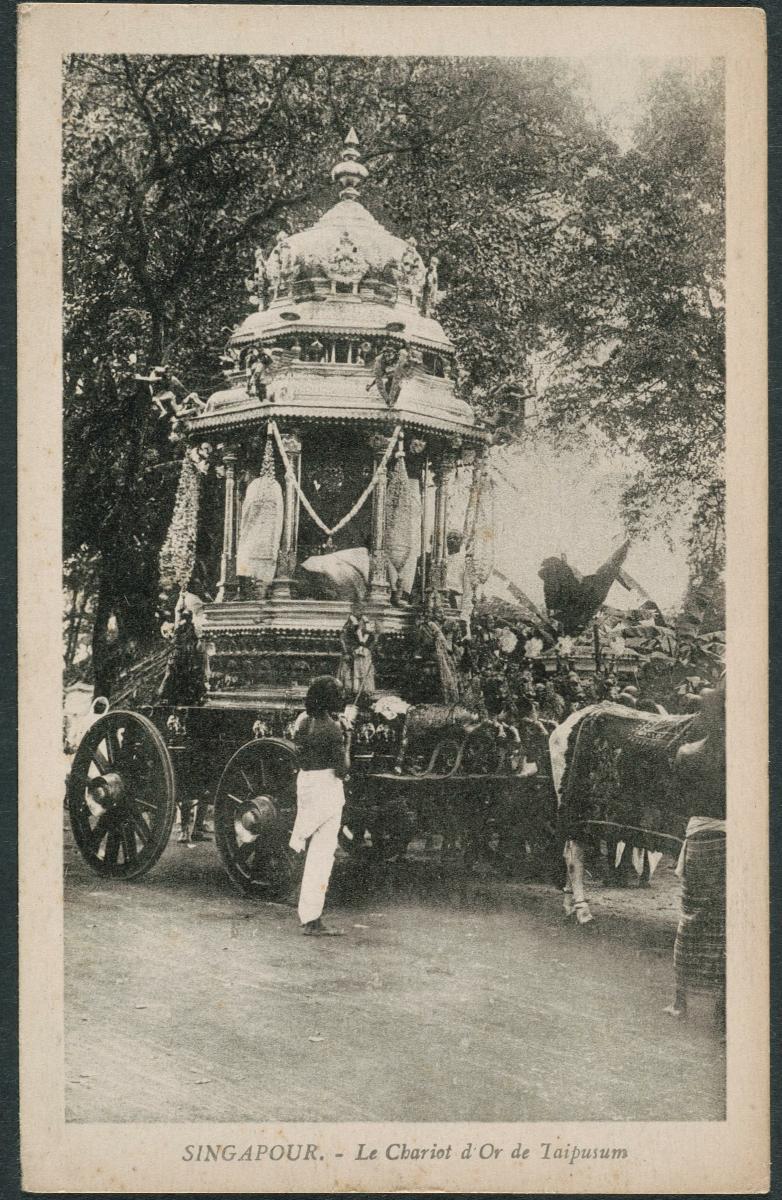

On the eve of Thaipusam, the processional Murugan image, placed in a silver ter (chariot), is taken on a procession through the city to Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Road, and then back to Sri Thendayuthapani Temple at Tank Road in the evening. This opening procession, known as Punar Pusam or Chetty Pusam, usually involves a predominant Chettiar gathering. A more elaborate procession takes place the following day and involves the participation of other Hindus and non-Hindus in the procession that commences at Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple on Serangoon Road and ending around four kilometres away, at Sri Thendayuthapani Temple.

The devotee is regarding as emulating Idumban, who mythology credits with lifting two hills. Another popular belief is that the devotee is the processional vehicle and the kavadi is a representation of Murugan’s shrine.

Bearing the kavadi is undoubtedly one of the most dominant features of Thaipusam, and receives great attention. The kavadi, traditionally consists of two semi-circular pieces of bent wood or steel attached to a horizontal structure.

To prepare for Thaipusam, a devotee may fast for about 48 days prior to the festival and will also adopt an austere lifestyle while fasting.

Devotees who have made vows will decide on the type of thanksgiving offering: a milk pot, a wooden pole with a pot of milk hung at each end, drag a chariot with hooks pierced in the body or carry an ornate structure held by spikes pierced into body.

On the day of the procession, volunteers help fix the kavadis onto the body of the carrier. This has to be done carefully, which is why people with special skills are needed. Offerings like milk pots and panchamirutham, which comprises five types of food such as banana, jackfruit, dates, honey, and sugar, are attached to the kavadi. The carrier then joins the queue to exit the temple and complete his walk of faith. The carriers are typically accompanied by supporters who encourage them onward in their procession of thanksgiving. At the end of the procession, the offerings carried are presented to Lord Murugan. This ritual is known as abishekam, and involves “pouring over the sacred vel with milk offered by the devotees”. The devotees then receive sacred ash from the temple and the kavadi is removed from the carrier’s body. The final ritual of the Thaipusam festival is idumban puja, observed in the devotees’ homes, and held up to a week after the day of the procession. This concludes the strict penance and fasting observed by the devotees in the days preceding the festival.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Murali Raj grew up among family members who participated regularly in Thaipusam. He was thus familiar with the festival traditions and carried his first kavadi when he was 18 years old. At first, it was due to a three-year vow he had made to Lord Murugan that he would carry a kavadi if he did well in his studies. However, he has since continued and has been involved in Thaipusam for more than a decade.

On the day of Thaipusam, he eats something light before he begins his prayers. Soon after, the piercing to attach the kavadi begins.

Present Status

In 2016, live music was permitted at designated locations along the procession route, as music was recognised as an integral aspect of the festival. In keeping with the changes in scale and festival practices, the Hindu Endowment Board and organisers Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple and Sri Thendayuthapani Temple work with government agencies on various preparations, such as applying for permits, setting up barricades along roads, ensuring sufficient security presence and other tasks to ensure the safe conduct of the procession.

Over time, the Thaipusam festival has become an important signifier of the cultural identity of the Singapore Indian community. The festival also plays an important role in building solidarity and cohesion across socio-economic backgrounds, and allows non-Indian communities in Singapore to witness and appreciate these vibrant cultures.

The devotion and commitment of the thousands who attend the festival suggest that Thaipusam will continue to thrive in Singapore. Mr Raj sees the festival as an important part of Singapore’s culture, but thinks that knowledge about Thaipusam often depends on how involved one’s family is with the event. He believes that more can be done so that people would understand Thaipusam better.

References

Reference No.: ICH-027

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Guy, John.Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.

Hindu Endowments Board. “Thaipusam Festival” http://thaipusam.sg. Accessed 3 June 2018.

Hindu Endowments Board. Glory of Murugan (special issue for Thaipusam). Singapore: Hindu Endowments Board, 2017.

Kent, Alexandra. Divinity and diversity: A Hindu revitalization movement in Malaysia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “Thaipusam in Singapore”, 10 February 1933.

http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/singfreepressb19330210-1.2.58.. Accessed 3 June 2018.