Making of Wood-Fired Pottery

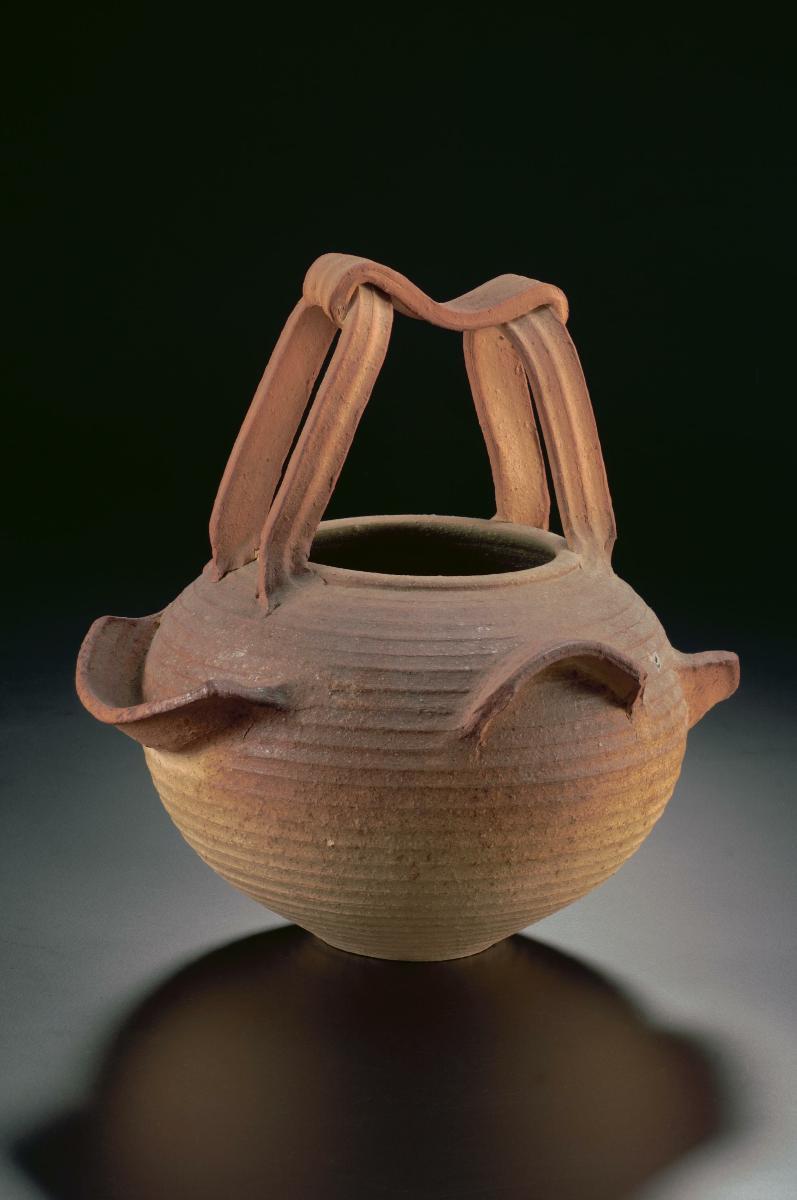

The production of traditional wood-fired pottery using dragon kilns draws on millennia of pottery traditions in China. Dragon kilns, mainly Hokkien and Teochew kilns, were constructed in Singapore in the early 1900s by migrants from South China.

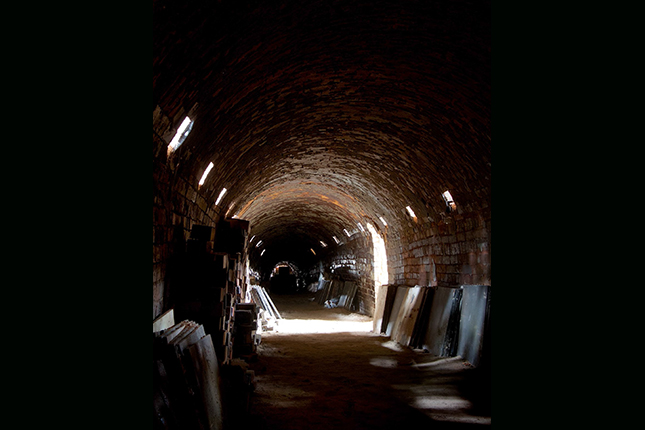

A dragon kiln comprises a long firing chamber built on a slope with many stoke holes on the side. The kiln is shaped like a dragon, with the head at the lower end and the tail at the upper end. The furnace is at the head of the dragon while pottery to be fired is arranged in the chamber on the ascending slope. The name “dragon kiln” may also be attributed to how it has a fiery, almost dragon-like appearance when being fired.

The temperature in the kiln chambers can reach nearly 1300°C. To use the dragon kiln effectively, one needs to possess technical knowledge that includes packing the pots appropriately before firing, knowing where to feed the wood, putting the wood through the stoke holes, and the sequencing of how to fire each chamber as required. The fly ash and volatile salts, as part of the wood-firing, give a natural ash glaze to the ceramic works.

Geographic Location

Chinese dragon kilns are also found in Southeast Asia and East Asia.

In Singapore, there used to be at least 20 kilns in Singapore located in Hougang (present-day Yio Chu Kang), Jurong, and Pulau Tekong, but there are only two remaining Teochew kilns today. They are Guan Huat Dragon Kiln (now under the Jalan Bahar Clay Studios) and Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln (now part of Thow Kwang Pottery Jungle). The latter, built in the 1940s, is the only functioning kiln today.

Communities Involved

The Chinese community in Singapore, involving mostly Hokkiens and Teochews, had constructed the kilns mainly in Jurong and Hougang (present-day Yio Chu Kang) due to presence of clay suitable for pottery. Teochew kilns can be traced to Fengxi Town, Chaozhou, Guangdong Province, China, which is regarded as the hometown for many Teochew potters, and known as the Town of Hundred Kilns (bai yao cun, 百窑村).

In the past, kiln workers formed the community that operated the dragon kilns in Singapore, and they were mainly involved in the manufacturing of pottery products for commercial or household use. Today, the people who fire the dragon kilns today are mostly those who produce pottery for artistic purposes. Various studios and community club groups continue to develop a vibrant and active pottery community. Wood-fired and dragon kiln pottery remain important for younger generation in Singapore to understand and appreciate the work of pioneers who were skilled in the traditional methods of creating intricate pottery pieces, a knowledge that has been passed down through the generations.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The dragon kiln is characterised by its “head”, “body”, and “tail” built upon a slope or hill, with the head lower than the tail. The “head” or firebox is where firewood is fed. First, firewood is burned in the firebox for 12–20 hours to dry the entire kiln. Often, there is a kiln-god altar located above it. Praying to the kiln god before the firing is a ritual still practised today.

The “body” of the kiln is where the pottery is placed. The pieces are carefully arranged in chambers along the length of the kiln according to their grades. They are stacked on top of each other or packed neatly on shelves, often separated by clay wadding and cockle shells. Pottery that can withstand higher temperatures are placed nearer the “head”. Temperatures can go up to 1,300°C at the “head” and 1,000°C at the “tail”.

The entrances to the kilns are sealed during firing, but there are “eyes” or stoke holes located along the “body” where firewood is fed. The fire can also be observed through these holes. An experienced potter can judge the temperatures in the kiln chambers based on the colours of the flames. These days, temperature sensors and pyrometric cones aid this process. Rising hot air pushes smoke out through the chimney at the “tail”.

Between 5,000 kg and 10,000 kg of firewood is fed to the kiln. The whole firing process can take three to four days, and the kiln is then left to cool for a week.

Potters are drawn to dragon kilns over their modern-day counterparts, the gas and electric kilns, because of the natural ash glaze that cannot be achieved by modern methods. This special glaze comes from the fly ash and volatile salts reaction, fusing and melting into the clay in the process of wood-firing. The unpredictable effects on colour and texture are what draws potters to dragon kiln pottery.

Experience of a Practitioner

Thow Kwang Pottery Jungle is owned by Mr Tan Teck Yoke and family. Mrs Yulianti Tan married Mr Tan Teck Yoke in 1980, and joined Thow Kwang. She learned the skills of dragon kiln pottery from her husband, Mr Tan Teck Yoke, and his family. Mr Tan Teck Yoke's father, Mr Tan Kin Seh, was a third-generation potter who left China in 1936. When he came came to Singapore, there was a demand for glazed latex cups for rubber plantations and water jars. Hence, he used the kiln to produce these ceramic wares.

Mrs Tan shared: “Kilns were located near the plantations to cut transport costs. Rubber trees were chopped down for firewood, and this formed a symbiotic relationship between the clay industry and the rubber industry.”

By the time Mrs Tan joined the trade in 1980, Thow Kwang was already slowing down its production, which eventually ceased in the late 1980s. In 2001, Mrs Tan decided to use the kiln for artistic production. She said: “The dragon kiln is something that my father-in-law left behind for us. I felt that I needed to keep it alive, if not for my father-in-law’s sake, then for mine as a member of this family to show my respect and gratitude towards my elders.”

Viability and Future Outlook

These days, dragon kilns are used to make pottery for aesthetic and lifestyle purposes rather the manufacturing of pottery products. Besides selling imported pottery, Thow Kwang has been conducting clay pottery workshops since the 1990s. During these workshops, participants create small ornamental items to be fired in the kilns. In an effort to make dragon kiln pottery commercially viable, Thow Kwang Pottery Jungle engages pottery instructors to conduct workshops to make pottery products, such as pots for flower arrangement and candle holders. These activities are enjoyed by both Singaporeans and international visitors.

Mrs Tan said: “The dragon kiln has gone through many phases, from being introduced to our country, to contributing to her rubber and clay industry, to ceasing production, and now being partly an educational tool. I want to share the dragon kiln with everyone, and make it a precious part of our culture worth (safeguarding).”

References

Reference No.: ICH-039

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Li, Lisa. “The last dragons in Singapore.” Medium, 6 December 2016, https://medium.com/kampung-seaport/the-last-dragons-in-singapore-12ade3f04b3c. Accessed 11 October 2017.

Miksic, John N. Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society, 2009.

Tan, Gia Lim. An Introduction to the Culture and History of the Teochews in Singapore. Singapore: World Scientific, 2018.

Thow Kwang Pottery Jungle and Dragon Kiln, https://thowkwang.com.sg/. Accessed 11 October 2017.

Zebracki, Martin and Palmer, Joni M. Public Art Encounters: Art, Space and Identity. Routledge, 2017.