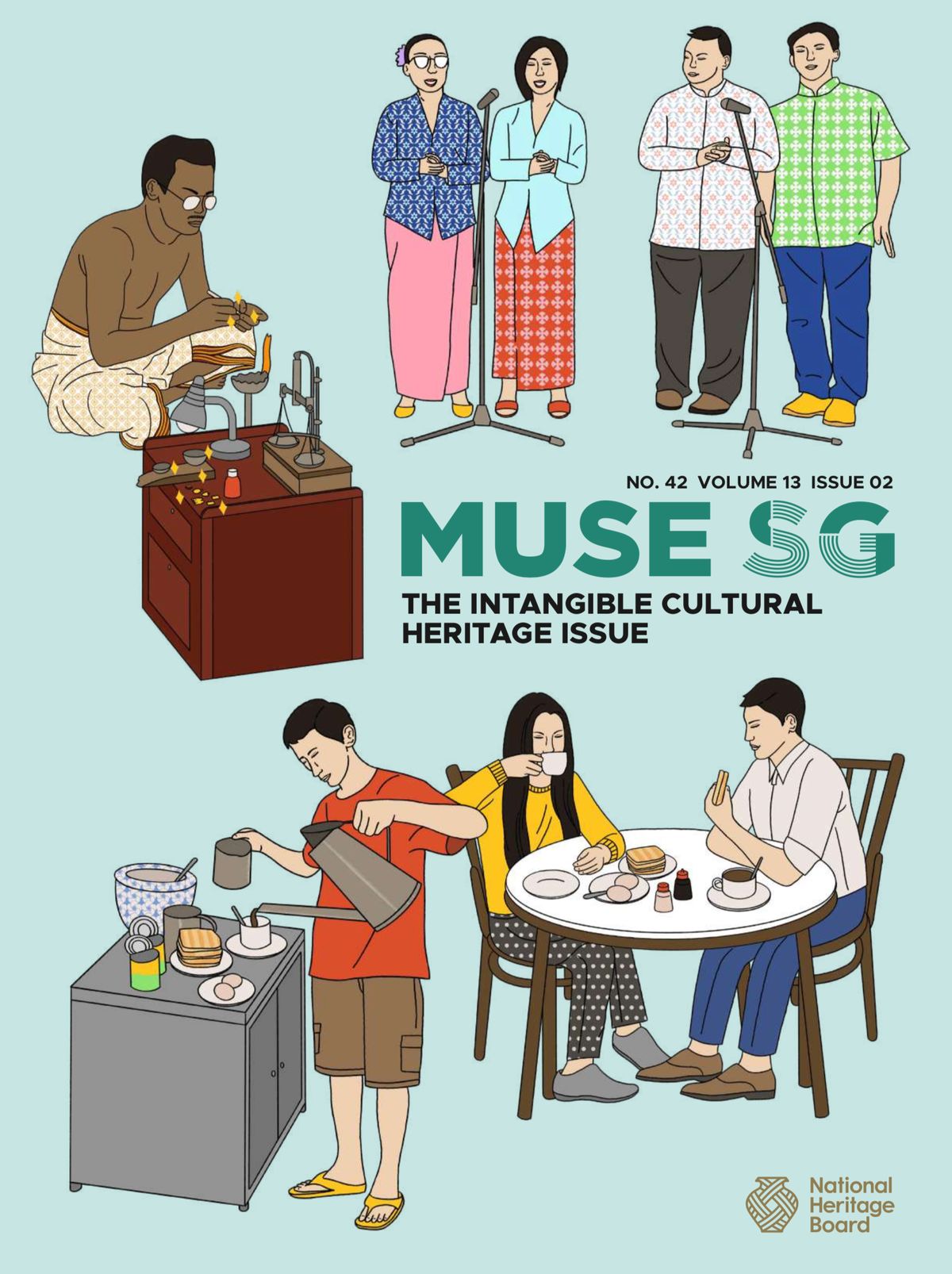

Chinese Cuisine in Singapore

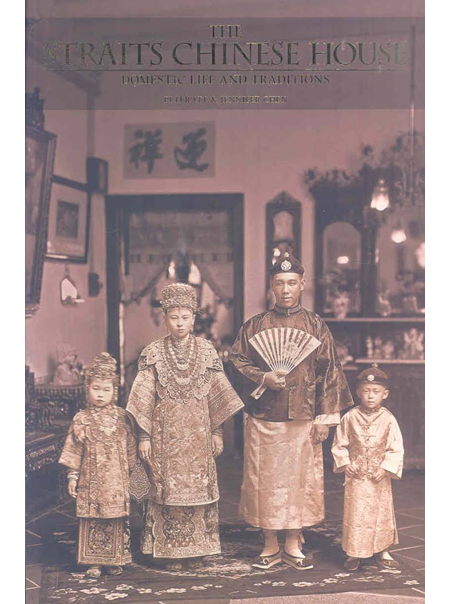

Traditional Chinese cuisine in Singapore, such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hainanese cuisines were brought to Singapore by the waves of Chinese immigrants of different ethnicities and origins in the 19th century. These cuisines have moved from simply being prepared for their respective communities to more diverse forms today. Dishes have evolved over time and some have incorporated ingredients found from the Southeast Asian region. The various types of Chinese cuisines in Singapore are also enjoyed by the non-Chinese communities. These trends reflect Singapore’s status as a multicultural community.

The styles and methods of cooking differentiate the cuisines from one another. Hokkien cuisine retains the original flavour of the ingredients to emphasise freshness and taste. Attention is paid to the savoury umami flavour of ingredients. Seafood is a common ingredient used in traditional Hokkien cuisine, due to the abundance of seafood in Fujian, China. Dishes like braised Hokkien noodles or ngoh hiang (五香; fried five-spiced pork roll) exemplify facets of Hokkien cooking, such as braising or stewing with dark soy sauce, ginger, and entire cloves of garlic, and the use of dips. Other notable dishes include braised pork buns (kong bak pau, 扣肉包), fresh spring roll (popiah, 薄饼), and oyster omelette (蚝煎).

Cantonese cuisine originates from Canton province. Its cooking techniques aim to bring out the flavour of the freshest ingredients, and dishes tend to have a shorter cooking time, be less greasy, and incorporate milder and simple spices. Common ingredients associated with Cantonese cuisine include ginger, garlic, spring onions, sugar, salt, soy sauce, rice wine and corn starch. The culinary techniques popularly associated with Cantonese cuisine include steaming, stir-frying, braising, stewing and smoking. Home-style cooking often emphasises soups, like lotus-root soup and old cucumber soup, while Cantonese cuisine offered by restaurants include dim sum (点心)— small dishes to be consumed with tea and congee, a savoury porridge. Other common dishes of Cantonese cuisine include barbequed meats (e.g. char siew, 叉烧) and soya sauce chicken.

Teochew cooking emphasises complementary condiments and dips, and combines multiple methods of cooking for a single dish. The “three treasures” of the cuisine are fish sauce, preserved radish pieces, and pickled mustard green. These can be found in iconic dishes like pork trotter jelly (猪脚冻), Teochew porridge (潮州粥), Teochew yam paste dessert (芋泥), braised duck slices (卤鸭片) and cold crab (冻螃蟹).

Hakka cuisine uses dried and fermented, or foraged ingredients — reflecting their status as “guest people” within provinces, often living away from the sea in uphill areas. Hakka cuisine emphasises the texture of the food, and common culinary techniques include stewing, braising and roasting. Classic dishes like thunder tea rice (擂茶饭) call for seven types of vegetable and five condiments including mugwort, sweet leaf, and three-leaved acanthopanax. Tea paste grounded with mortar and pestle is served with rice and vegetables. Other popular Hakka dishes in Singapore include abacus seeds (算盘子), Hakka yong tau fu (客家酿豆腐), preserved vegetables with pork belly (mei cai kou rou, 梅菜扣肉), and Hakka-style salt baked chicken (盐焗鸡).

The Hainanese were among the later groups of Chinese to make their way to Singapore and Southeast Asia. Many Hainanese found work as cooks in British military camps and home of British expatriates during the colonial period, and learned western techniques of cooking that influenced their cuisine. The Hainanese also adapted cuisines from Hainan island to local ingredients and tastes. The most famous dish associated with the Hainanese chicken rice, which was adapted from a well-known Hainanese dish called Wenchang chicken (文昌鸡). Other notable Hainanese dishes include Hainanese pork chop, Hainanese curry rice, Hainanese mutton soup and stir-fried chives with squid and glass noodles (鱿鱼韭菜炒冬粉).

Geographic Location

Chinese cuisine in Singapore originated from the different provinces in China. Hokkien cuisine is largely from Quanzhou, Zhangzhou and Xiamen in Fujian province; Cantonese cuisine from Guangdong province; Teochew cooking stemming from the Chaoshan region; Hakka cuisine has influences from the communities within provinces in China who lived in uphill areas; while Hainanese cuisine were associated with Hainanese migrants.

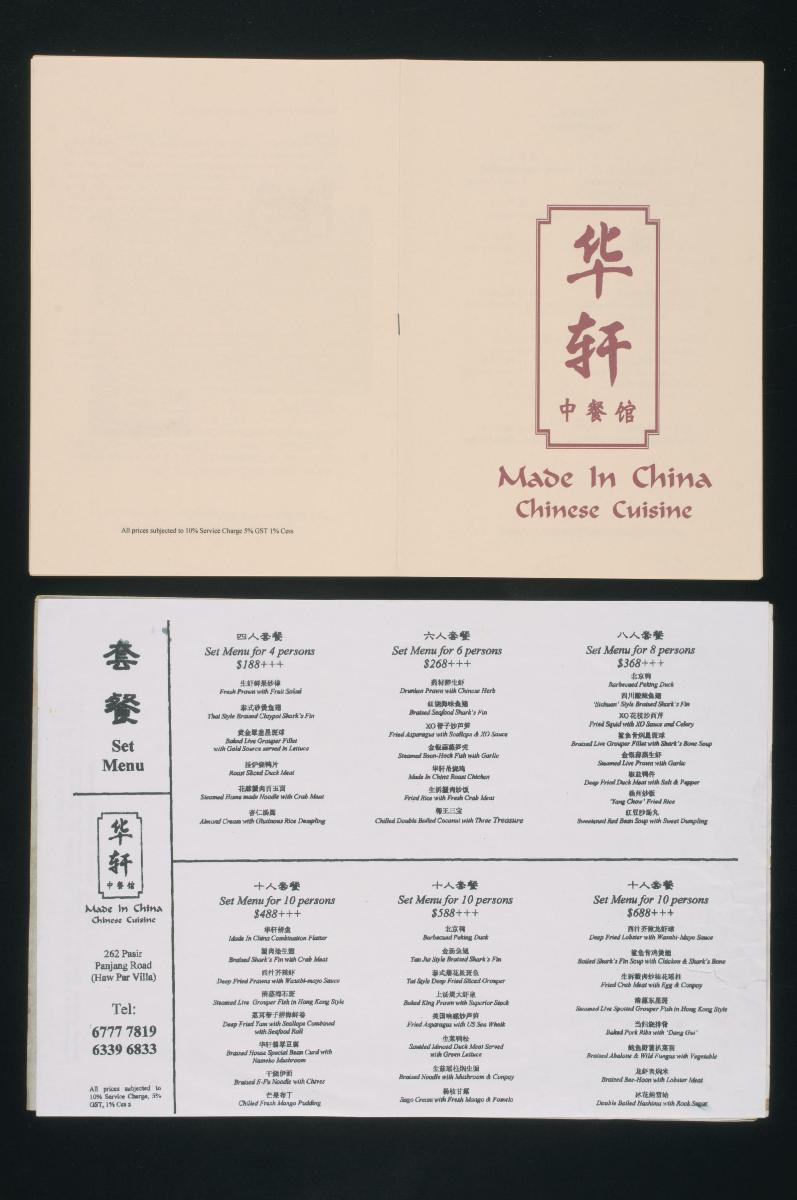

Chinese cuisine in Singapore today can be found at a variety of establishments, from neighbourhood hawker centres to more upscale, elaborate restaurants. Families also continue to cook the cuisines of their respective dialects within households.

Communities Involved

The Chinese community in Singapore is involved in the practice and transmission of Chinese cuisine, which is also enjoyed by the wider community.

While various types of Chinese cooking were brought to Singapore throughout waves of immigration in the 19th and 20th centuries, the practices and traditions of the cuisines here have been influenced by some organisations and notable restaurants.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Chinese dishes and cooking techniques in Singapore have many differences from their international counterparts, reflecting the availability of local ingredients and the influence of different dialect and ethnic groups. Changes range from small ones, like how popiah (薄饼; Hokkien spring roll) is known as lumpiah in Indonesia, to more substantial differences in contents and preparation. This same dish in China contains cabbage instead of turnip, lacks prawns or chilli paste, and thus has a sweeter and plainer taste. Cantonese roasted meats are braised for a shorter time in Singapore to suit local preference for firmer textures. Other differences in cooking, such as the smaller amounts of alkaline water added to braise Hokkien noodles, have emerged due to local health regulations.

The role that certain Chinese dishes play in local festivals and cultural traditions has also evolved. Yusheng (鱼生), a salad with raw fish and assorted condiments, is commonly eaten in Singapore today during Chinese New Year, with a group of diners collectively tossing the ingredients while shouting loud auspicious sayings to celebrate the festival. This dish was said to be invented here in 1964 by four local chefs dubbed by the media as “The Four Heavenly Kings” for the pivotal role they played in shaping Cantonese cuisine in Singapore. Restaurants from other dialect groups have since adapted the dish with their own ingredients and serving styles.

Traditional Chinese cuisine requires extensive skills and practice to be made well, and different practitioners have devised different methods in passing on the knowledge and technique necessary to preserve Chinese cooking. One such restaurant, Hung Kang Teochew Restaurant has worked with other Teochew affiliated groups such as clan associations and other Teochew restaurants to promote Teochew cuisine and culture, while local Hakka chef Mr Pang Kok Keong has shared recipes adapted and modernised for younger cooks, such as a variation on the Hakka salt-baked chicken.

Experience of Practitioners

Mdm Soon Puay Keow operates the Cantonese Spring Court restaurant, first started in 1929 by her father-in-law, while Mr Lai Fak Nian and Mr Ng Han Kim are founders and owners of the Hakka Plum Village Restaurant (established 1969) and the Hokkien Beng Hiang restaurant (established 1978), respectively.

Each practitioner identifies strongly with the work in their restaurants, seeing it as a means of highlighting the culinary practices and knowledge of their respective dialect group. Mdm Soon says her restaurant is a platform to showcase the “traditional flavours”, something she takes pride and responsibility in doing. Meanwhile, the walls of Mr Ng’s Beng Hiang restaurant are adorned with works of calligraphy pertaining to Hokkien cuisine and entrepreneurship.

The restaurateurs see a close relationship between the specific traditions of their cuisine and a wider awareness of the culture of their dialect group. Mr Lai believes that understanding Hakka culinary practices is crucial to the continuation of Hakka culture as a whole. Hence, beyond running Plum Village Restaurant, he teaches and shares Hakka recipes with schools and clan associations and has published a cookbook with the Nanyang Khek Community Guild.

Watch: Hakka Cuisine

Present Status

The sustainability of these cuisines depends on younger chefs and cooks who are willing to carry on the trade. High rental and operating costs are also challenges for the restaurants.

Nevertheless, restaurateurs have taken steps to preserve the knowledge and skills required for Chinese cuisine. Mr Charlie Lim Kheng Chuan, manager of Hung Kang Teochew Restaurant, actively encourages senior chefs to pass down their knowledge to junior chefs, emphasising friendly competition through his policy of treating each chef equally. Due to manpower demands, the restaurant has hired chefs of various dialect groups. However, Mr Lim ensures adherence to specific styles of cooking to retain “traditional Teochew cuisine elements”, which are the main draw of his restaurant. It would truly be “a great pity”, he says, if this traditional cuisine with Singaporean characteristics were to be lost. As long as local food enthusiasts of all ages and ethnicities become increasingly discerning, traditional cuisines such as these will always have a strong following.

Resources

A project by Ngee Ann Polytechnic (Chinese Media and Communication) Students

Kakinang Network. “Culture and Heritage”, 2018, kakinangnetwork.wixsite.com. Accessed Dec 2018.

References

Reference No.: ICH-045

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Cantonese Cuisine

Choy Wai Yuen.Madam Choy’s Cantonese Recipes.Singapore: Epigram, 2012.

David Y. H. Wu and Tan Chee Beng.Changing Chinese Foodways in Asia. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2001.

Klein, Jakob A. “‘For Eating, It’s Guangzhou’: Regional Culinary Traditions and Chinese Socialism.” Chapter 2 in Enduring Socialism: Explorations of Revolution and Transformation, Restoration and Continuation, edited by Harry G. West and Parvathi Raman. Berghahn Books, 2013.

Min Ding and Jie Xu. The Chinese Way. Routledge, 2014.

Phillips, Carolyn. All Under Heaven: Recipes from the 35 Cuisines of China. United States: Ten Speed Press, 2016.

Wu, David Y. H. The Globalisation of Chinese Food. Surrey: Curzon, 2002.

Hakka Cuisine

Plum Village Restaurant. “Hakka Food." http://www.hakkafood.com.sg/. Accessed 22 July 2017.

Chan, Margaret. “A tongue for dialects.” The Straits Times, 26 June 1988.

Goh, Kenneth. “Keeping Hakka recipes alive.” The Straits Times, 10 July 2016.

Lau Anusasananan, Linda. The Hakka Cookbook. California: University of California Press, 2012.

Hokkien Cuisine

Beng Hian Restaurant. “About Beng Hiang.” http://www.benghiang.com/about. Accessed 21 November 2017.

Chua Beng Huat & Ananda Rajah “Hybridity, Ethnicity and Food in Singapore.” In Wu David Y.H. & Tan Chee-beng (eds) Changing Chinese Foodways in Asia.Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2001.

Loo, Anthony Hock Chye & Samantha Lee.Uncle Anthony’s Hokkien Recipes. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2015.

Teochew Cuisine

Low, Eric.Teochew Heritage Cooking: A Treasury of Recipes for Chinese Comfort food. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2015.

Wu, David Y.H. & Sidney C.H. Cheung.The Globlization of Chinese Food. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002.