TL;DR

Previously a common ingredient in Chinese households, the salted fish is most associated with Cantonese cuisine today. This preserved ingredient - with a pungent smell - has found itself at odds with contemporary palates over the last century in Singapore.

By Wong Pui Lam Lydia (NTU History Programme)

Salted fish is, as its name implies, fish that has been salted. This simple process utilises a single ingredient – salt to preserve fish as it extracts water out of the fish and also prevents the growth of microbes. Salted fish is consumed in different traditional cuisines around the world, especially in places close to the seas and oceans. In Chinese cuisine (both that of maritime Southeast Asia and China), the use of salted fish is most associated with Cantonese cuisine due to the large number of dishes that use the ingredient. It is traditionally consumed not only because of its long shelf life but also, more importantly, for the distinctive flavours that it brings. Just like soy sauce (liquid condiment made from fermented soy beans), bean sauce (fermented bean paste made from soy beans), fish sauce (liquid condiment made from fermented fish) and salted vegetables (fermented and brined vegetables), the ingredient makes a dish savoury and imparts a unique, deeper taste not found in plain salt or in any of the above mentioned ingredients.

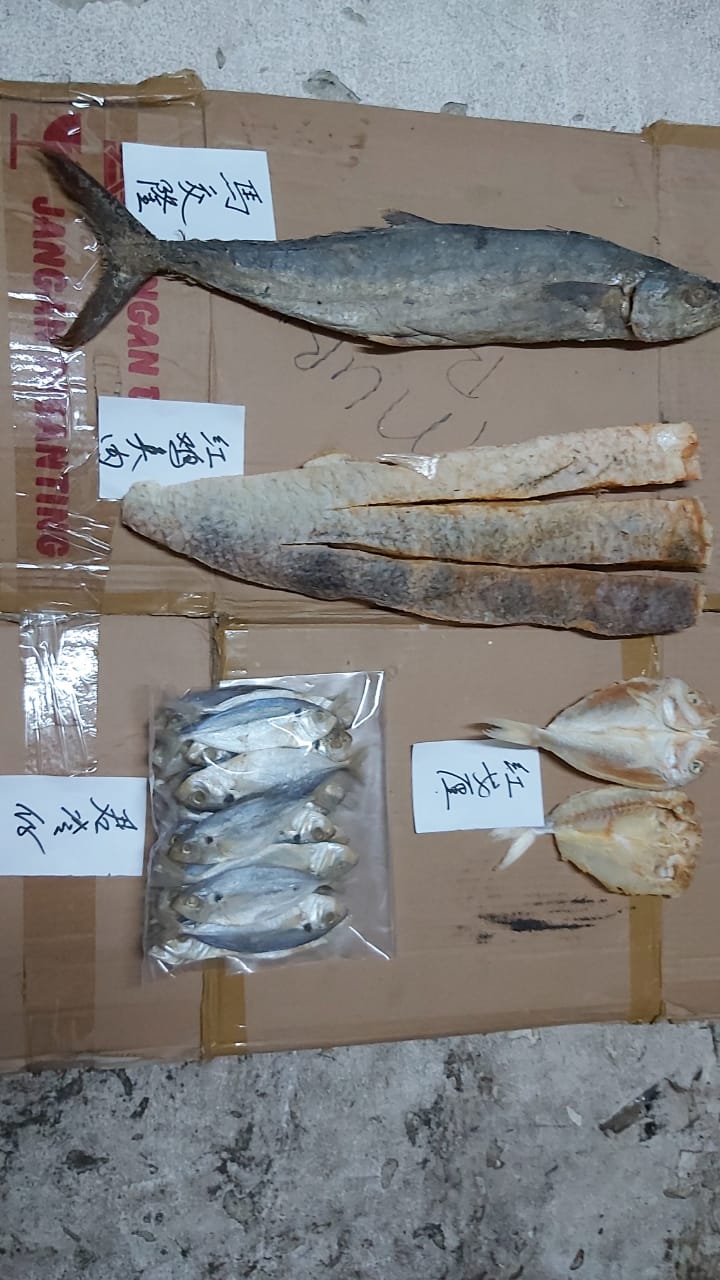

The salted fish used in Cantonese cuisines is not necessarily restricted to a particular species or type of fish. Fishermen, whether deep-sea fishers or those operating in the intertidal zones closer to shore, had traditionally salted the fishes they caught to preserve them, minimising losses from spoilage. Besides the variety of fish species, there are also varieties to the method of drying and the resultant product. In most cuisines around the world, the salted fish commonly used is that with a hard flesh (a result of the drying process the fish undergoes). For the salted fish used in Cantonese cuisine, it is separated into two types: sat yoke (實肉) and muiheung (霉香/梅香). Sat yoke means hard flesh and is similar to most salted fish found in other traditional cuisines. For the muiheung (霉香) variety, mui (霉) means mold and heung (香) stands for fragrance, which provide clues to how the muiheung salted fish is prepared and the reasons for its popularity. While any fish can be made into the muiheung salted fish, the Spanish mackerel (ma kao yu, 马交鱼) and threadfin (ma you yu, 马油鱼) are preferred due to its high fat content, fleshy meat and bigger bones which allows for easier deboning. To prepare a muiheung salted fish, one has to ferment the fish – the process known in Cantonese as faat mui (发霉) or faat gau (发酵) – for a number of days before commencing salting and drying. The additional fermentation of the fish results in a crumbly paste-like texture and a unique scent. Those accustomed to the smell describe it as “fragrant”, while others can be put off by it.

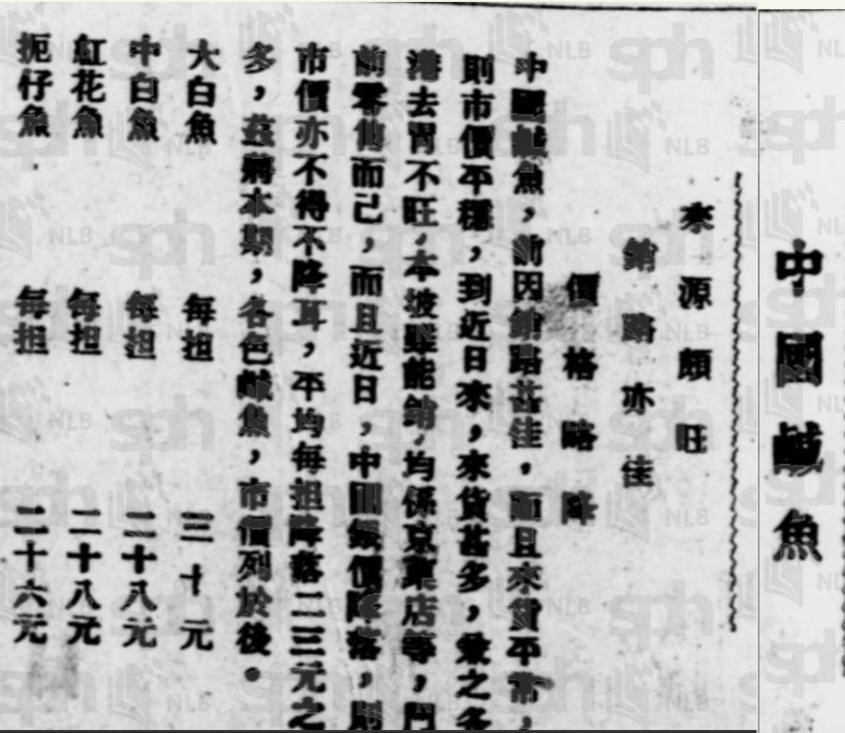

Singapore has long been an important regional entrepôt and centre for the salted fish trade. Its supply of salted fish came from different places like Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, Hong Kong and parts of South China. The Nanyang Siang Pau in pre-war Singapore reports on salted fish supplies and prices regularly, in full page spreads, alongside essential food items like eggs, oil and rice, and precious metals like gold. The price of Chinese salted fish was reported to be sold at a cheaper price in Singapore than in some places of production like Malaysia. Today, most of the salted fish sold in Singapore’s dried good stores or supermarkets are from Malaysia and Indonesia.

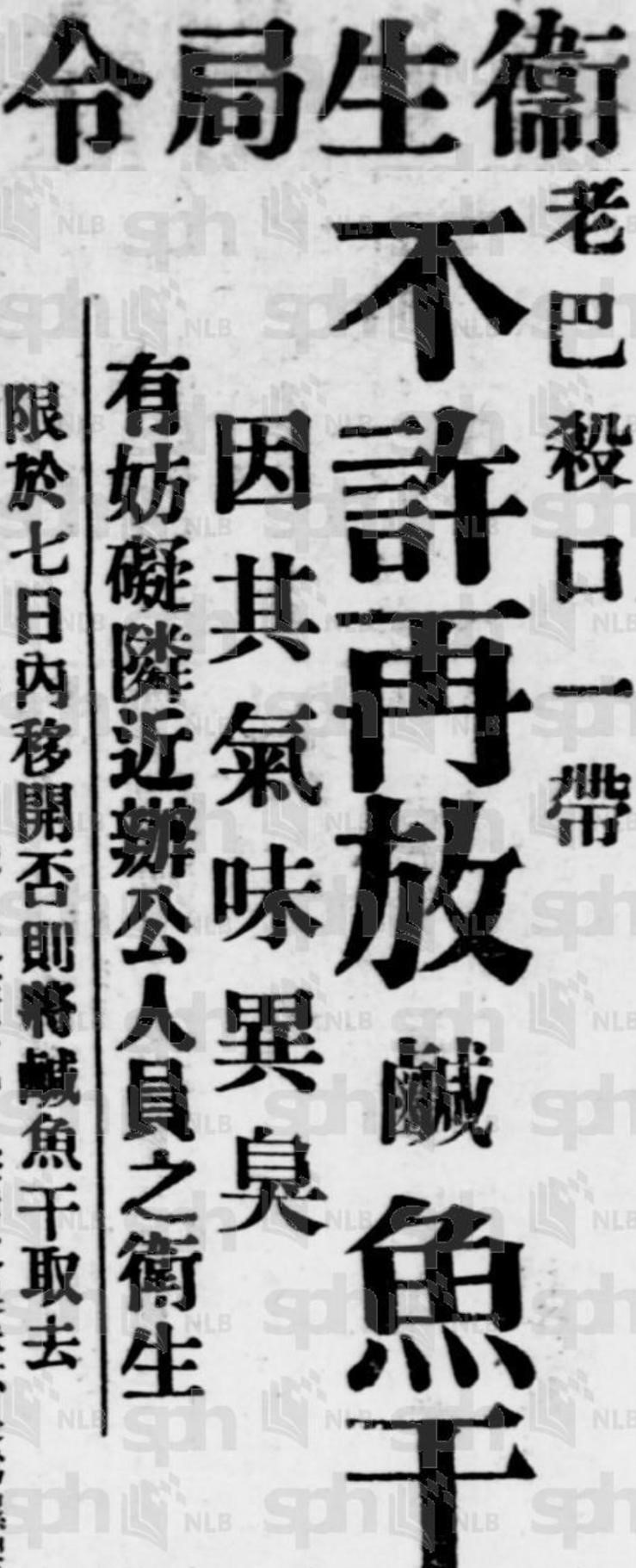

Over the last century, the consumption of salted fish has often been discouraged and viewed negatively. In colonial Singapore, the Sanitary Board banned the sale of Chinese salted fish at Lau Pa Sat on one notable occasion in 1934. The foul smell was perceived to be a threat to the area’s hygiene and also to the health of government officials working there. The issue was eventually resolved through intervention of the General Chinese Trade Affairs Association (present-day Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce & Industry) with the complete removal of the item from the affected dried seafood retailers. This episode, however, did little to reduce the viability and consumption of salted fish among the Chinese in pre-war Singapore.

Up till the 1970s, salted fish continued to be a common food item as it was cheap and alongside with salty ingredients like preserved vegetables, its salty taste was thought to help people consume more rice which filled their stomachs more. In emerging discussions around nutritional health in the Nanyang Siang Pau in the late 1960s, salted fish along with preserved sausages were described as vital sources of protein in an otherwise carbohydrate heavy diet. However, reports in the 70s began surfacing on the possible link between nasopharyngeal cancer and salted fish which then gradually affected the demand for the commodity. By the 1990s, salted fish had come to be perceived as being synonymous with cancer and its consumption discouraged. With reduced sodium intake for health reasons and increased disposable incomes increasing the affordability of fresh fish, the consumption of salted fish has declined continually over the years. One wonders what the future holds for this historically important food item. Will there be a revival in its culinary use or consumption? Or would it become a relic of the culinary and food history?

Special feature: Song Garden, Mercure Hotel Bugis

Every now and then, I will crave for the delectable and fragrant scent of the salted fish. Chef Huang Shea Neung who serves Cantonese cuisine at Song Garden, Mercure Hotel, kindly prepared a feast that featured salted fish in every dish served. Chefs in zau laus (酒楼) – high-end Chinese restaurants, pride themselves in being able to cook special dishes requested by the customers, as long as the ingredients are available. The dishes served were claypot rice with preserved sausage, chicken and salted fish, fried rice with salted fish, stewed tofu with minced meat and salted fish, mini char siew buns with salted fish and lastly, mini chicken pies with salted fish. The first three dishes were not on the menu and the latter two mini-bite pastries were unique creations that Chef Huang prepared for this occasion. Ingredients like salted fish and dishes cooked with claypots would not have been served in zau laus as they were considered unpresentable in these places associated with fine dining. Salted fish dishes that we see in zau laus today are due to more people (with higher disposable incomes as the economy improved) dining there and requesting for dishes commonly cooked and consumed at home. It is this new demand that perhaps provides the greatest hope for the survival and future of this delicacy.

Credits

Special thanks to Eng Kiat for his enormous wealth of knowledge on food and for connecting me to the incredible Cantonese chefs like Chef Huang Shea Neung at Song Garden, Mercure Hotel who kindly cooked a storm of dishes starring Chinese salted fish, Chef Cui who kindly shared on how the use of Chinese salted fish in Cantonese cuisine in Singapore evolved over the decades and salted fish producer A Tjap, all whom without this photo essay could not have realised. Lydia Wong is a history graduate from Nanyang Technological University. Having previously written her thesis on the trade of Chinese salted fish in 1930s Singapore, her research interests are food history, history of east Asia and the overseas Chinese diaspora.

About partner

Wong Pui Lam Lydia (NTU History Programme)

The NTU History Programme strives to be a leading centre for researching and teaching interdisciplinary, Asian, and world/transnational history, while pushing innovative and immersive approaches to learning about and exploring Singapore's past and heritage. It welcomes students, scholars, and interested members of the public to join us in these endeavours! Find out more about our programmes, research, and events at https://www.ntu.edu.sg/soh/about-us/history or find us on Twitter (@NTUHistory)!

This photo essay was produced as part of the Singapore HeritageFest (SHF) 2021.