Text by Michelle Chan Yun Yee

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

In 1996, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore (URA) published a brochure advertising Punggol as the “waterfront town of the 21st century”. Indeed, Punggol has a longstanding heritage of being a town that boasts of living and relaxation by the waters. However, like a wave, the trajectory of Punggol’s reputation as a waterfront recreational retreat has undergone a series of crests and troughs. Hailing back to the colonial era, Punggol’s idyllic setting was first disrupted by the Japanese Occupation of Singapore from 1942-1945. Following the war, Punggol saw a re-emergence of its recreation scene. This resurgence, however, was again interrupted by the Northshore Reclamation Project during the late 1980s. In fact, it was only in the late 1990s that Punggol began to fully reclaim its name as a place for recreation, culminating in its image today as a waterfront town. This article explores Punggol’s history, in particular its waterfront and recreational heritage, which has endured many moments in time to become what it is today.

Early Punggol

Today’s Punggol refers to the area bounded by Tampines Expressway and the two rivers, Sungei Serangoon and Sungei Punggol. However, from the colonial era up to the 1970s, Punggol extended beyond this demarcation to include the sub-districts of Sengkang and Buangkok. This large historical boundary explains why Punggol has both coastal as well as agricultural characteristics; the latter further suggested by the meaning of its place name.

The first use of the name “Pongul” (eventually evolving into “Punggol”) was by John Turnbull Thomson in his 1844 land survey map. The etymology of the name “Punggol” has many possible explanations, though they all share Malay origins. Also sometimes spelt as “Ponggol”, the name means “hurling sticks at the branches of fruit trees to bring the fruits down to the ground”.5 Alternatively, it can also be translated as “a place where fruits and forest produce are offered for wholesale”, implying that Punggol was a rural, agricultural area.6 A third explanation involves the man who started Punggol village – Wak Sumang. In an interview with the National Archives of Singapore, his great grandson Awang bin Osman claimed that Wak Sumang gave Punggol its name after obtaining the go-ahead from the British government to start a new village.7 While Wak Sumang was clearing his garden, a large tree was burnt and its branch, known as punggur in Malay, fell on his hut. He then decided to name the village “Punggur”.8 These interpretations of Punggol’s etymology suggest origins based on its rural location and bucolic landscape.

Relaxing in Remote Punggol

Punggol’s rural atmosphere and relative isolation from the Downtown Core of Singapore made it a suitable place for retreat and recreation. Punggol was so remote that it could only be accessed via two roads – Serangoon Road and Punggol Road.9 In fact, public transport into Punggol was sorely lacking until 1935, when one bus route was finally introduced by the Ponggol Bus Service Company.10

Europeans living in Singapore certainly recognised that Punggol was the ideal retreat location since a few of them chose to build their bungalow-style country houses there. The Matilda House is one such bungalow that has withstood the test of time to become an iconic landmark in Punggol. Irish lawyer Alexander William Cashin built the Matilda House as a present for his wife, and it served as a weekend house for his family.11 It comprised an extensive fruit garden, and a view of the Punggol River estuary and the Straits of Johore.12 Boasting amenities such as stables and tennis courts, it provided its occupants with various sources of recreation.13 In fact, swimming in a pagar (a lagoon formed by stakes driven into the nearby sea) was something that his son Howard Cashin distinctly recalls.14 This perception of Punggol as an ideal place of retreat from the city was possibly what drew wealthy Europeans to build their houses there, forming the basis of Punggol’s association with recreation.

Apart from the Europeans, other visitors were also drawn to Punggol by two major attractions – the Japanese Fishing Pond and the Basapa Zoo. The Japanese Fishing Pond shifted from Changi to Punggol, opening on 24 December 1927.15 There, visitors could catch their own fish to cook and consume fresh from the waters.16 About a hundred yards away was the Basapa Ponggol Zoo.17 Owned by William Lawrence Soma Basapa, in 1928, it moved from its original location at Serangoon Road to a 10-hectare plot near the Punggol seafront along the former Track 22 as it had grown too large for its previous location.18 The zoo was immensely popular among local residents, especially on weekends.20 The zoo also won praise with a generous feature in Sir Roland Braddell’s 1934 book, The Lights of Singapore. Inside, the zoo was described as “a truly delightful place” and that “a trip to the zoo is one of the things that no visitor should omit; it has a personality entirely its own, and is pitched in beautiful surroundings on the Straits of Johore”.20 Being Singapore’s only zoo at that time, it was commonly dubbed “the Singapore Zoo”, even though it was privately owned.21

Peace Disrupted

The arrival of the Japanese in 1942 severely disrupted the serenity of Punggol. The first salvo was fired when the British ordered Basapa to relocate his animals and birds within 24 hours as they wanted to use the Basapa Zoo land for defence against the imminent Japanese arrival.22 Basapa failed to do so and the British shot his animals and freed the birds.23 True enough, the Japanese used Punggol Beach as one point of entry to invade Singapore.24

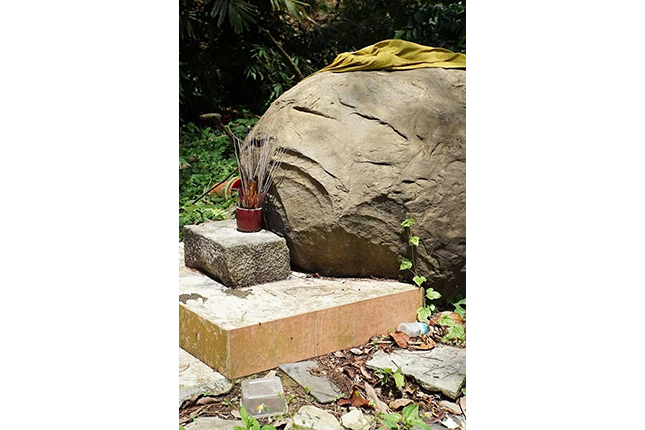

During the Japanese Occupation, Punggol was infamously known for the Sook Ching massacres. Sook Ching, meaning purging through cleansing in Chinese, was conducted by the Japanese occupiers and primarily targeted Chinese communities perceived to be hostile to the Japanese. The process began with screening of Chinese men aged 18 to 50 by Japanese Kempeitai officers and their informants. Those singled out as anti-Japanese would be arrested and brought to one of the several sites designated for execution. Punggol Point was one of them. On 28 February 1942, about 300 Chinese civilians were executed by the auxiliary military police firing squad at Punggol.25 The Indian Daily Mail reported an elderly fisherman, Peh Ah Boh, visiting Punggol after the massacre and personally witnessing more than ten corpses floating on the waterfront.26 The legacy of the Sook Ching on Punggol stretches as far as 1998, when a newspaper report called Punggol Point the “Slaughter Beach”. It reported that “[a] man digging for earthworms to use as fishing bait... found parts of a human skeleton instead”.27

An aerial view of Punggol Point, 2014.

An aerial view of Punggol Point, 2014.

Image courtesy of the Housing & Development Board.

Apart from animals and humans, Punggol’s infrastructure was also badly affected with the majority of bungalows as well as the Japanese Fishing Pond destroyed. Punggol’s recreation scene had become almost non-existent. Through the Japanese Occupation, Punggol gained a new reputation, not associated with recreation but with death and destruction.

Recreation Resuscitation

After the Japanese Occupation, life slowly seeped back into Punggol. In spite of the beach’s darkened history, residents living near the coast continued life as before. For these residents, the waterfront was an integral part of their lives. Abigail Chew, who lived near Punggol Point in the late 1970s, recalls: “The sea was so near my home that it would hit against the fence [of my house].”28 Her daughter, Anna Chew, still has memories of playing at the beach, wading into the sea and climbing into the sampans tied to stakes.29

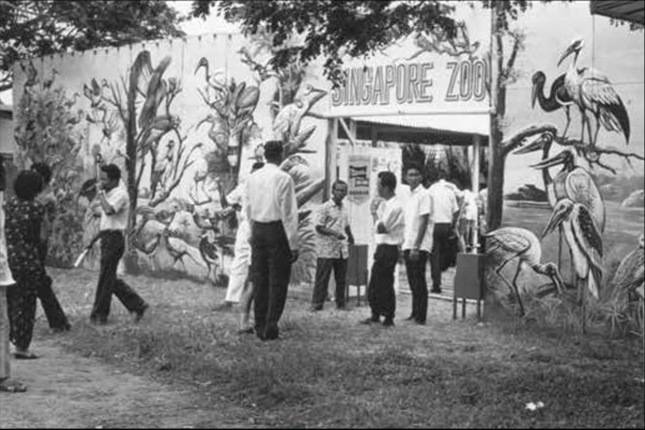

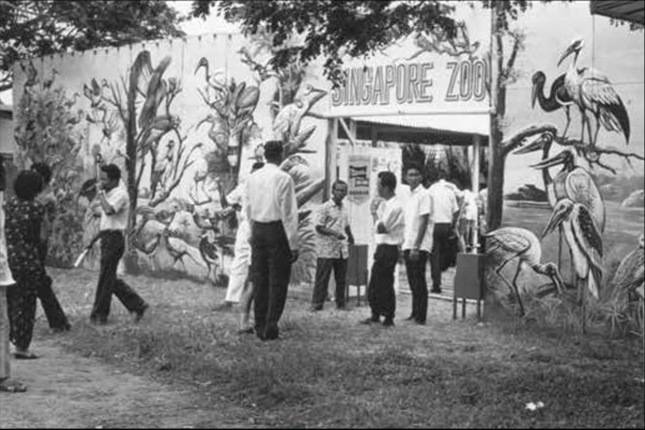

It was during this post-war period that Punggol’s reputation as a place for recreation grew in prominence once more. Remnants of old attractions in Punggol could be seen, albeit with some differences. For instance, in 1963, Chan Kim Suan, a landowner and animal lover, opened another zoo at Punggol.30 Called “Singapore Zoo”, it had only 70 animals, making it significantly smaller than Basapa Zoo, which had comprised 200 animals and 2,000 birds during its peak. Furthermore, it was less popular than Basapa’s zoo as it was visited mainly by Chan’s friends.31

The former Singapore Zoo at Punggol, 1965.

The former Singapore Zoo at Punggol, 1965.

Primary Production Department Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Singapore Zoo shuttered in the early 1970s due to financial woes.32 Apart from the return of the zoo, a newly built Ponggol Rest House also occupied the site of the former Japanese Fishing Pond.33 Claiming to be the “ideal seaside health resort”, it boasted a hotel, bar and restaurant, and featured activities such as picnics, boating, water skiing, fishing and swimming.34

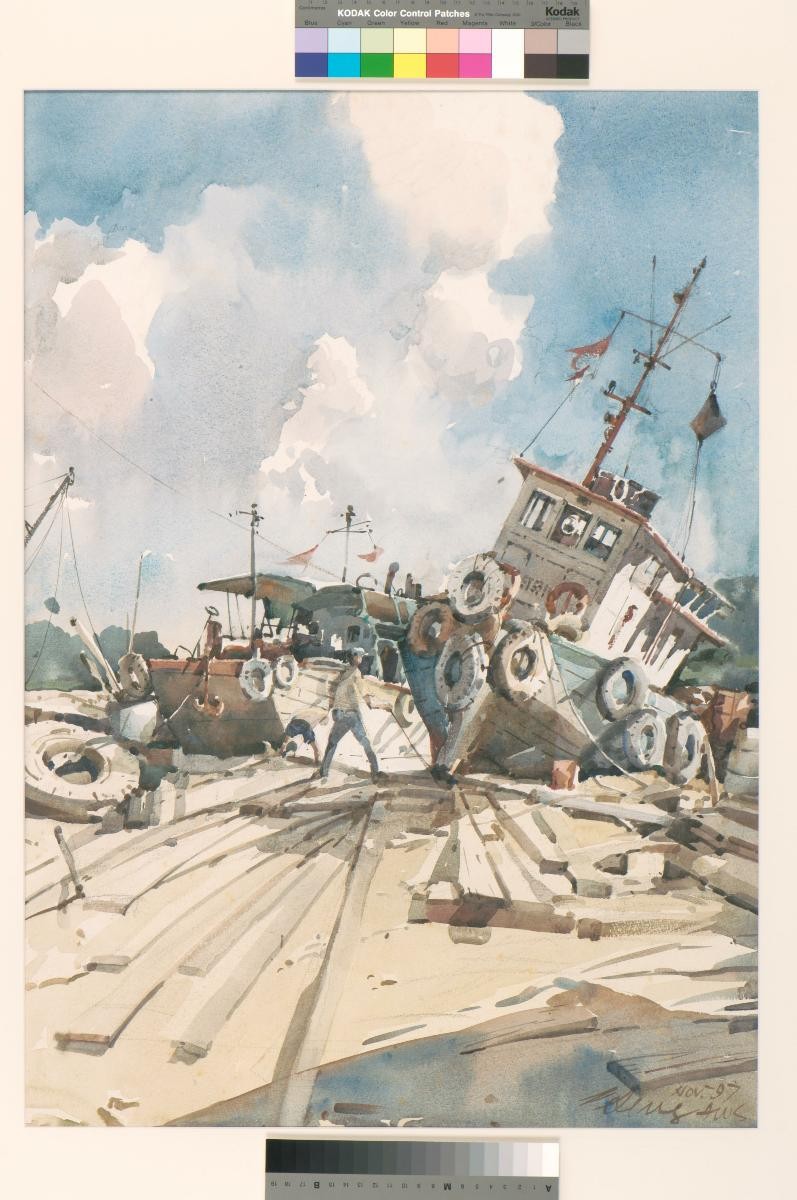

However, it was the new attractions established over the subsequent decades that really brought Punggol back to life, adding to its bustle. One major draw to Punggol was its seafood offerings. A notable example would be the Sea Palace Kelong Restaurant cum Nite-Club set up in Punggol in 1969.35 It was Singapore’s only kelong-style restaurant nightclub and was built over stilts at Punggol Point, providing a novel seaside experience for diners.36 Moreover, it was said that its seafood could not come any fresher as they were caught right off the surrounding waters.37 Unfortunately, the restaurant burnt down in 1972 due to unknown reasons and never reopened again.38

A wooden kelong at Punggol, c. 1905.

A wooden kelong at Punggol, c. 1905.

Image courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Nevertheless, this did not spell the demise of the food scene at Punggol as other seafood restaurants continued to draw in the crowds. The cluster of seafood restaurants at Punggol Point became known as Seafood Village, where chilli crab, butter prawns and deep fried baby squid became part of a list of must-order dishes. Writing in The Straits Times in 1990, Margaret Chan describes the atmosphere of Seafood Village:

Eating seafood at Punggol Point is like eating seafood nowhere else in the world. Imagine on a weekend night, a crowd of 6,000 at one sitting... the Ponggol Restaurant alone sits almost 2,000 at one time. If this is not exciting enough, take a table at the end of the road so that you can eat while massive SBS buses negotiate three-point turns within touching distance of you. Talk about living dangerously.39

The competition between restaurants and the good quality of Punggol’s seafood cemented Punggol’s reputation as the go-to place for delicious seafood and waterfront dining.

Seafood restaurants by the beach at Punggol Point, 1993.

Seafood restaurants by the beach at Punggol Point, 1993.

Lee Kip Lin Collection, image courtesy of the National Library Board, Singapore.

Water sports were another type of activity that added to the bustle of Punggol. Fishing, for example, had gained such a repute that then Vice-President of USA Richard Nixon asked about it during his visit to Singapore in 1953.40 In addition, skiing and boating were also done along the coastline.41 Punggol Beach was the choice venue for a number of events such as the Singapore Powerboat Association 1982 Regatta, 1983 7-Up Water Ski Series and 1983 Easter Boat Show.42 By 1986, there were eight boatels (waterside hotels) in Punggol, including Marina Beach Resort, which was one of the largest in Singapore.43 Besides providing docking facilities for travellers’ boats, the boatels also rented out boats for water-skiing, fishing and sightseeing.44

A group of teenagers having a picnic at Punggol Board, 1949.

A group of teenagers having a picnic at Punggol Board, 1949.

Wong Sin Eng Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Indeed, the post-war era in Punggol saw a resurgence of the area’s recreational scene. With the many attractions and events associated with its waterfront location, Punggol’s identity and heritage as a place of recreation was cemented.

Waterfront Town of the 21st Century

In 1982, it was announced that Punggol would be redeveloped in the mid-1990s.45 The reclamation of land under the Northeastern Coast Reclamation Project would establish Punggol Town, which would eventually become a waterfront residential town of the 21st century, as envisioned by the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Housing & Development Board (HDB).46

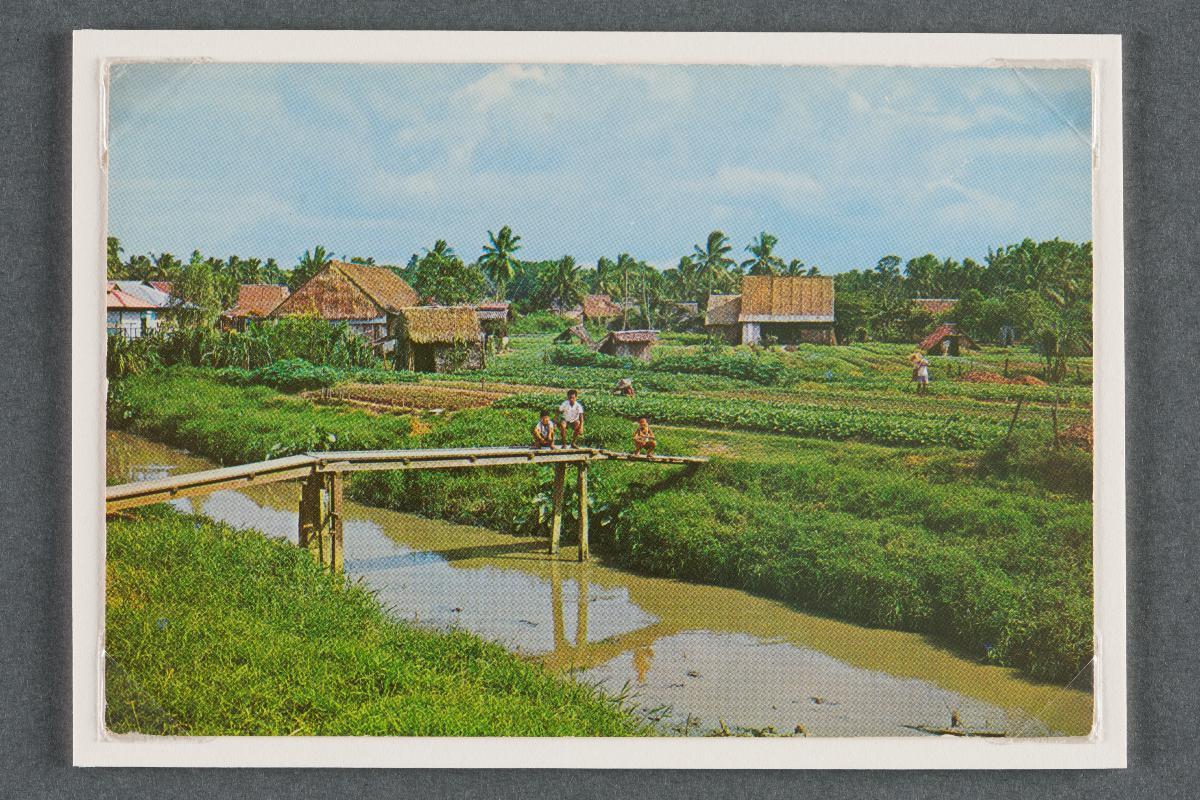

These redevelopment plans affected the sea-fronting and pig farming industries located further inland.47 The latter was part of an official nationwide plan to curb pollution by phasing out pig farming and importing pork instead.48 The last of 22 pig farms in Punggol closed by November 1990, with some former farm owners shifting to hydroponic vegetable and orchid farming, as well as other businesses.49 In order to make way for land reclamation, the boatels, seafood restaurants and people living between Punggol Track One and Seven were given till the end of 1994 to relocate.50 Once developmental work went into full swing, Punggol’s former recreation scene receded from the public eye.

A vegetable farm at Punggol, c. 1970s.

A vegetable farm at Punggol, c. 1970s.

Image courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Even though redevelopment plans hit a snag during the 1990s and early 2000s due to the Asian Financial Crisis, Punggol Town today is finally experiencing a revitalised recreation scene.51 Some of the new amenities in Punggol have their roots in the past, representing a continuity with Punggol’s heritage. One example is Punggol Marina Club. Although Punggol’s boatels of the 1980s were closed due to land reclamation works in the early 1990s, they returned in the form of the Punggol Marina Club, which opened in 1996.52 This private club was formed by a group of former Punggol boatel owners (namely Awang Boat Sheds, Zainal Water-ski Centre, Marina View and Yap Boatel), who helped to provide temporary boat storage facilities during the redevelopment phase.53 Another example is the Punggol Settlement at Punggol Point, which was completed in 2014.54 Punggol Settlement currently houses a number of seafood restaurants, reminiscent of the former Seafood Village. Ponggol Seafood Restaurant, which was at Punggol Point from 1969 to 1994, has even returned, joining the other restaurants at Punggol Settlement.55

Awang Boat Sheds, a former boatel run by Awang bin Abdullah at Punggol Point, 1985.

Awang Boat Sheds, a former boatel run by Awang bin Abdullah at Punggol Point, 1985.

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In addition, a new water catchment area named Punggol Waterway was also opened in 2015.56 Waterfront living now resurfaces through the HDB flats, a shopping mall named Waterway Point, the SAFRA complex and the Punggol Polyclinic, which flank the waterway. Coney Island, opened in 2015, was another integral part of the envisioned Waterfront Town.57 Developed as a park and green space, Coney Island is linked by bridge to the Punggol Waterway Park Connector.58 These recreation amenities have added to Punggol’s waterfront legacy, honouring its heritage and perpetuating its identity as a place for recreation.59

An aerial view of Punggol Town, with Coney Island in the background, 2014.

An aerial view of Punggol Town, with Coney Island in the background, 2014.

Image courtesy of the Housing & Development Board.

Conclusion

While Punggol’s reputation as a retreat space has gone through numerous crests and troughs, it is undeniable that waterfront recreation has always been an integral part of its identity. Although the waterfront branding was an intentional effort made by physical planners, this identity is one that has roots in the area’s heritage. At the same time, the events of the Japanese Occupation also imprinted the tragedy of the Sook Ching massacres onto the town’s history. For the generation that went through the Japanese Occupation, Punggol Beach will always be associated with the suffering that many experienced during this period – so much so that the beach gained the moniker: “Singapore’s Slaughter Beach”.60

Nevertheless, for others – especially the younger generation of Singaporeans – this dark past does not eclipse the exciting recreational offerings that Punggol is known for today. As Francis Tan, a restaurant owner at Punggol Settlement, says: “I don’t let the dark past get to me. I chose this place for my restaurant because it has a beautiful view of the sea.”61 The redevelopment of Punggol has undoubtedly brought about a new commitment to its reputation as a waterfront town, giving the place its new nickname – “waterway”. With Punggol reclaiming its historical identity, the area has come full circle, with new generations of Singaporeans now sharing in and expanding the collective memory of Punggol’s waterfront heritage.

Awang Boat Sheds, a former boatel run by Awang bin Abdullah at Punggol Point, 1985.

Awang Boat Sheds, a former boatel run by Awang bin Abdullah at Punggol Point, 1985.

Image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Punggol Waterway Park, 2018.

Punggol Waterway Park, 2018.

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board.