By Andie Ang

Images: Andie Ang, Marcus Chua & Daniel Koh

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2014

Travelling along the arboreal forested highways with graceful four-limbed locomotion is an enigmatic acrobat in a black coat of fur: The Banded Leaf Monkey.

Visitors to local parks and nature areas such as MacRitchie Reservoir and Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (BTNR) would be familiar with the sight of sizeable troops of monkeys foraging by the trails. Known as the Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis), this opportunistic primate has managed to thrive despite widespread disturbance of its habitats, its omnivorous habits and tolerance of humans. A few regard the macaques as nuisances, but to others, their presence adds a rare touch of the wild and wonderful to life in the urban jungle, and many weekend warriors savour the opportunity to see this versatile survivor of Singapore’s natural heritage.

Not many people, however, are aware of another monkey that dwells in the deeper parts of our nature reserves. Unlike the long-tailed macaque, this creature seldom descends to the ground and would find human treats unpalatable and indeed, harmful, to its health. And though it was once found all over Singapore, it now survives only in small patches of forest in the heart of the island.

Shy and Scare Vegetarians

A study in black and white, the Banded Leaf Monkey (Presbytis femoralis) is a startlingly pretty animal with midnight fur and ivory bands traversing the underside of its body and limbs. A diversity in hairstyles is often observed; while the scruffy, unkempt look is the most popular, an upswept Mohawk hairdo is also not rare.

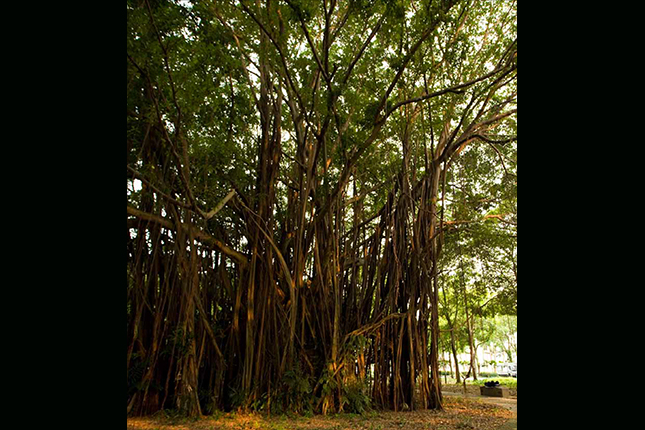

Photo: Daniel Koh.

Unlike the long-tailed macaques, which happily snack on insects and bird’s eggs when given the chance, the banded leaf monkey advocates strict vegetarianism, consuming primarily fruits and immature leaves. However, typical Singaporeans that they are, they are extremely picky about their diet. Depending on the season and the availability of favoured fruits, the monkeys travel long distances in order to procure suitable food, which contrary to popular belief is not always abundant everywhere in the forest. Thus, their survival may hinge on the continued existence of sufficient and uninterrupted expanses of forest that would allow the monkeys to locate their preferred food sources. The constraints of living in land-scarce Singapore is as much a reality to them as anyone else; the leaf monkeys share their minuscule forest plots with Singapore’s two other native primates: the aforementioned long-tailed macaques and the rare Sunda Slow Loris (Nycticebus coucang), a wide-eyed, fluffy thing that comes out only at night to feed on fruit, nectar and insects.

Shy by nature, the banded leaf monkey is almost always the first to crash away into the depths of the jungle upon seeing a human. This comes as no surprise, given that these monkeys were frequently trapped as pets and poached for the cooking pot by people many decades ago. In those earlier, more innocent days, scenes of banded leaf monkeys leaping in an orderly line across the forests emitting calls that can be heard kilometres away were common throughout the island.

Up to the 1920s, banded leaf monkeys were still reported to be widespread in various areas including Bukit Timah, Changi, Pandan, Tampines, and Tuas, where industrial estates and shopping malls presently stand. Deforestation for urban development led to the relentless shrinking of their habitat, confining them to isolated woods in the BTNR and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR); a decline which, unfortunately, did not stop there. On October 1987, an elderly female believed to be the last banded leaf monkey in the BTNR was mauled to death by dogs as she climbed down a tree. She now rests in peace at the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR), a formalin-drenched reproach in charcoal and horn. With the subsequent construction of the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE) right across the two reserves, habitat availability for wildlife dwindled as the remaining two green lungs of Singapore were disconnected, arresting biodiversity exchange and leaving the CCNR as the last refuge of the banded leaf monkeys in Singapore.

“We must do whatever we can, together with the rest of the world, to slow down the loss of biological diversity. Let’s try to do something to conserve the banded leaf monkeys because it is a very powerful symbol of what we are trying to do in Singapore to conserve the endangered species, both of plants and trees as well as mammals.”

- Professor Tommy Koh, Ambassador-at-Large, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Chairman, National Heritage Board. Professor Koh was speaking as guest-of-honour at ‘An Evening Dedicated to Conserving Singapore’s Biodiversity,’ a seminar organised by the National University of Singapore on 16 April 2010.

Taking Stock of our Natural Heritage

Singapore’s incessant march towards greater development in the past century has also contributed to a severe decline in the diversity of her native wildlife species. Some are sadly believed to be beyond rescue, such as the Cream-coloured Giant Squirrel (Ratufa af nis). This cat-sized rodent was first described from Singapore in 1821, but only two individuals were last sighted by 1995. Previously described by Sir Stamford Raffles as being abundant in the forests, this species is probably already extinct in Singapore.

On a similar note, some 30% of the total native vascular plant flora (namely flowering plants, conifers and ferns) is presumed nationally extinct, with another 30% regarded as critically endangered in Singapore as of 2010. This deterioration in local species richness and abundance is a call for urgent action in research and measures to conserve the endangered species that still survive in Singapore, lest they go the way of the cream-coloured giant squirrel.

The banded leaf monkey was first described from our nation in 1838 and is considered Critically Endangered in Singapore. Based on fur colouration and other physical characteristics, some scientists believe that the banded leaf monkey may be a subspecies unique to Singapore, differing from populations in neighbouring Johor, Malaysia. As a key representative of our natural heritage, the banded leaf monkey deserves a high priority in conservation. However, the difficulty in tracking and observing these enigmatic primates has been a major factor deterring researchers from studying them. Little is known about their natural history and ecology, except that their population size was estimated at just 10 in the 1980s and approximately 20 in the 1990s.

Recent Discoveries Bring Hope

My strong interest and love for primates propelled me to carry out a Master’s research project on the banded leaf monkey in Singapore, 15 years after the only other study done on this elusive species. With generous funding from the Ah Meng Memorial Conservation Fund by Wildlife Reserves Singapore and logistical support from the National Parks Board, I spent nearly two years trudging through the tangled expanses of the forest.

But this effort has finally paid off. We estimate the present local population to consist of at least 40 banded leaf monkeys as of 2010, two times greater than previously believed. We have also provided the first report on their reproductive biology and infant development, and found encouraging signs that the population may be recovering. In addition, food plant species have been identified through feeding observations, the first preliminary analysis of their feeding ecology. This provides valuable information on the species of trees the monkeys require to adequately feed and thrive.

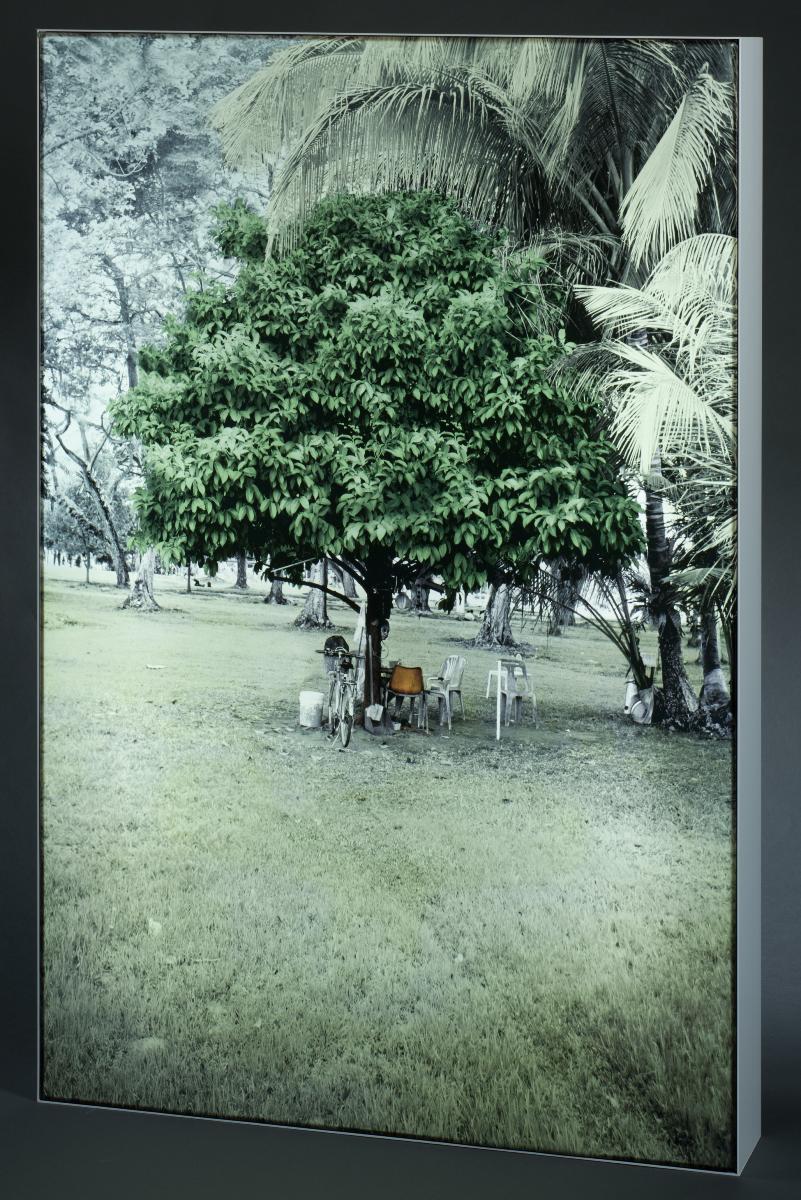

Photo: Andie Ang.

Furthermore, we have clarified the taxonomic debate on whether the Singapore population is the same subspecies as that in Johor through genetic studies of their faeces. Contrary to prior belief, the banded leaf monkeys in Singapore and Johor are likely to be the same subspecies, elevating hopes of possible translocation and reintroduction of the species in both localities in order to ensure their long-term survival. A comparative study on the different populations of the banded leaf monkeys is therefore essential towards a deeper understanding of their population ecology. With a research grant from the Jane Goodall Institute in Singapore, I will be continuing my research on the banded leaf monkeys, this time on those found in Malaysia.

Despite depressing news of various species going extinct over the years, some heartening rediscoveries in Singapore’s natural heritage do help to lift the spirit a little. For instance, during my research on the banded leaf monkey, we rediscovered several plant species previously thought to be locally extinct. And in 2008, Marcus Chua, a fellow student at the National University of Singapore, rediscovered the greater mousedeer (Tragulus napu) with signs of a breeding population in Pulau Ubin during his field research. These are the results of a continuous effort in scientific research into local biodiversity, and demonstrate the importance of regular studies and monitoring in order to provide timely updates on species abundance and distribution. Hope is not all lost!

Photo: Marcus Chua.

The preservation of our natural heritage requires concerted efforts from each and every individual of the society. The findings of my research on banded leaf monkeys, which were possible thanks to the support of both the public and private sectors, are evidence of this. Contributions from and collaborations between researchers, educational institutions, government bodies and non-governmental organisations can enhance the quality of biodiversity research and increase the appreciation of our national treasures, many of which are uniquely Singapore’s. Strong public support and interest is also vital to conservation efforts, as citizens become aware and more appreciative of Singapore’s natural heritage and the need to strike a balance between urban development and maintaining the health and biodiversity of our remaining forests.

Andie Ang is a Graduate Research Fellow in the Evolutionary Biology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore. For more information on her research, visit http://evolution.science.nus.edu.sg/monkey.html