Text by Dr. Nanthinee Jevanandam

BeMuse Volume 6 Issued 2 - Jul to Sep 2013

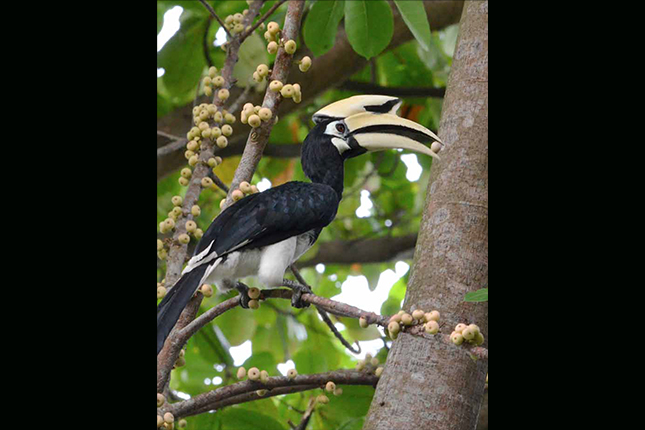

"It's a bright and early morning at Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and I am going about my usual fieldwork when I hear a ruckus going on at a nearby tree. Walking over, I see a flurry of activity: long-tailed macaques are hopping from branch to branch, plantain squirrls are scurrying about, and a variety of birds are flocking to a great big tree that is covered with thousands of small, red, juicy fruit. It's a feeding frenzy, and the host?"

- A Fabulous Fig Tree

Figs (or Ficus as this group of trees are known in Latin to botanists) are often touted as "keystone species", which means that these trees play a disproportionately large role in the lives of many creatures in an ecosystem. One key reason for this significance is that fig trees provide food for a great number of other animals in the forest. One research study has found that over 1,270 species of mammals and birds, as well as a number of reptiles and fish, feed on figs to varying degrees (Shanahan et al. 2001). In addition, many other tropical rainforest trees are seasonal, producing fruit only in certain months or even certain years, whereas figs bear fruit all-year round, thus providing reliable and nutritious source of food for forest-dwelling birds and other beasts.

A fruit with a long history

Wild figs have existed for millions of years but their use in agriculture by our ancestors appears to have originated as far back as 11,400 years ago in the Near East. This was established in 2006 by archaeologists from Israel and the United States who found the remnants of dried figs at an archaeological site in the Jordan Valley (Kislev et al. 2006). Their discovery, which was published in the journal Science, suggests that figs were being used in agriculture even before olives and grapes, making them the oldest cultivated fruits to date

Most figs that are cultivated by mankind are varieties of a single species, Ficus carica, also known as the Common Fig. The name carica comes from Caria, a region in Asia Minor that is now part of Turkey. Turkey is the world’s large producer of figs, accounting for approximately 27% of the total production of figs, followed by Egypt, then the USA. In Asia, figs are cultivated in Japan and China, but these are mostly retained for the domestic market. The cultivation of figs and the recognition of their nutritious quality have helped spread the fig far and wide. Today, figs are found wherever the weather permits and are cultivated in regions outside their native range like France and California

Trees that depend on tiny wasps

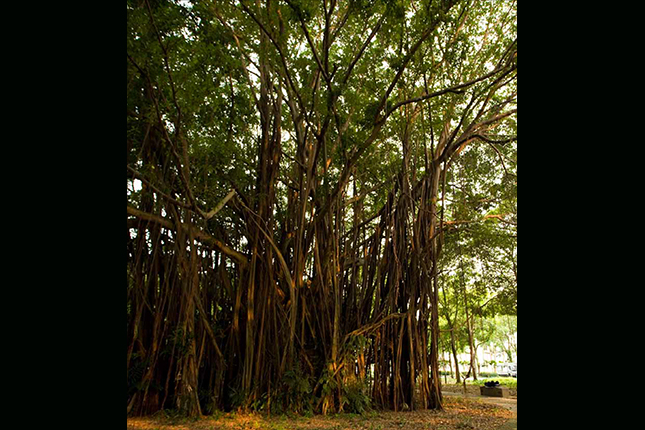

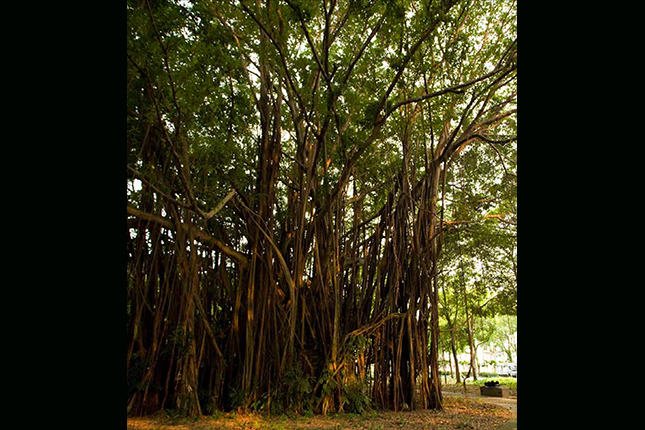

Despite their widespread cultivation and popularity as culinary treats, few people are aware that aside from Ficus carica, there are more than 700 species of figs worldwide. Approximately 500 species can be found in Australasia, making this region the most diverse for figs. Some of the most well-known local trees are figs; readers are surely familiar with Banyans or Strangler Figs (Ficus benjamina or Ficus microcarpa), which begin life as tiny seeds deposited on the branch of another, already mature, tree by a passing bird. The fig sapling then sprouts and sends down roots towards the ground. These aerial roots, which confer a rather spooky atmosphere to these figs, later thicken and ‘strangle’ the host tree, which dies off. The Banyan that remains forms a thick canopy with a dense latticework of roots, which provide ample habitat for other plants and animals. In the ruins of the Angkor Wat complex in Cambodia, large strangler figs have taken over some temple compounds, their roots enveloping the ancient stone walls and gopurams with a layer of living wood.

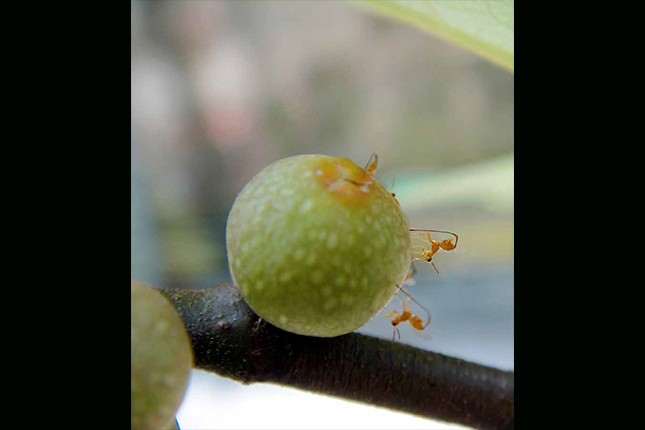

Another little-known fact about figs is that these magnificent, life-giving trees are completely dependent on tiny wasps measuring just a few millimetres in length, which are the only insects able to successfully pollinate their flowers. These fig wasps are very different from the hornets and other social wasps that visit flowers in parks and gardens and nest in elaborate hives; fig wasps do not feed as adults, lack stings and are totally harmless to humans; in fact, without fig wasps, we would have no figs at all.

Figs and fig wasps share what is known to ecologists as a reciprocal obligate mutualism. This means that both partners cannot reproduce without the other. The relationship is made more complex by the fact that approximately two-thirds of all fig species have a one-to-one relationship whereby each species of fig tree can only be pollinated by a single species of fig wasp. Thus, the extinction of the pollinator would mean the extinction of its associated fig tree as well.

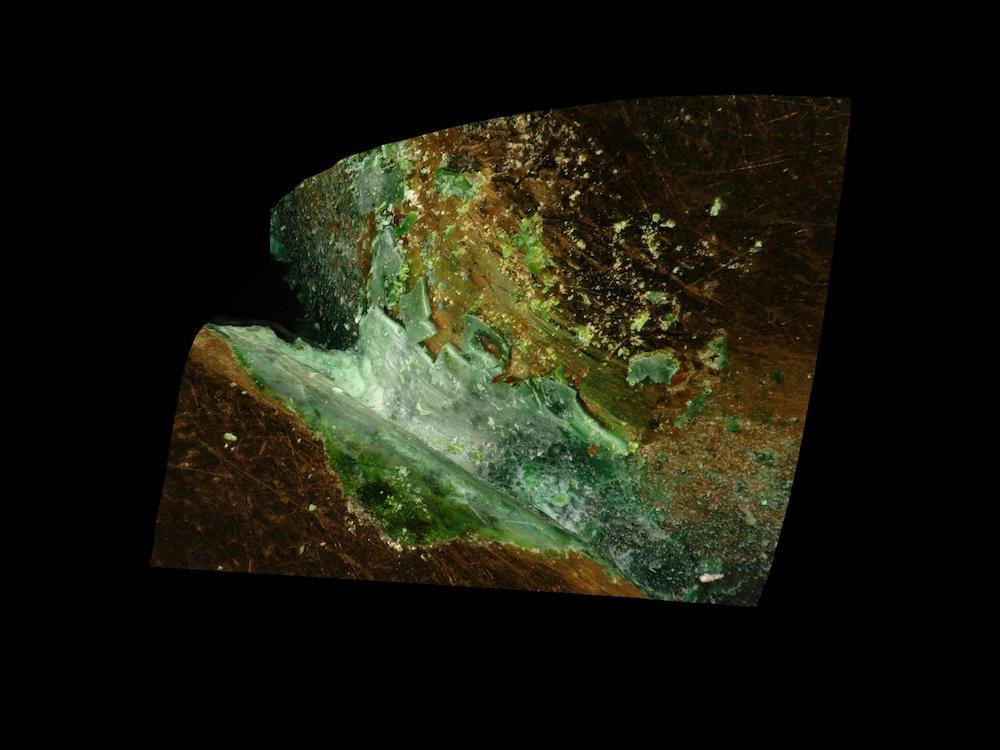

The Chinese refer to figs as ‘Wu hua guo’ or ‘flowerless fruit’, a name which aptly describes the distinctive reproductive features of figs. Instead of showy flowers that bloom in the open from the tips of branches, figs produce an enclosed receptacle that is full of hundreds of tiny individual florets. This receptacle, called the syconium, is often thought to be the fruit, but it is not a fruit until pollination has taken place.

At the bottom of this receptacle, keen observers will see a tiny entrance called the ostiole. This hole serves to allow the female fig wasp to enter the syconium. She then proceeds to simultaneously pollinate the fig and lay her eggs. Her offspring, when they finally emerge as adults, will then mate with each other within the syconium. The male wasps die after mating, but the mated female will exit the syconium via the ostiole, carrying pollen on her body as she flies off to find other figs of the same species. When she reaches and enters a new syconium, the pollen on her body fertilises the fig and the life-cycles of both tree and wasp are repeated. In the meantime, the pollinated florets in the syconium will ripen and turn the receptacle into a delectable fruit enjoyed by humans and frugivorous animals. In short, the fig tree provides a nest for the offspring of the fig wasp, and in return the fig wasp pollinates the flowers of the fig. It is a mutualism that has lasted over 60 millions years and ensured the survival of both groups of organisms.

In Singapore, figs are the second large genus of woody plants with 48 recorded native species, of which 32 (66%) are considered critically endangered or nationally extinct (Chong et al. 2009). This is largely the result of deforestation, which has replaced nearly all of the island’s original vegetation with urban spaces that support only a handful of hardy fig species such as Banyans. Another, more pervasive, threat to the survival of all species of figs is the possibility that their tiny pollinators will go extinct. A study carried out by my colleagues and myself using four species of fig wasps found in Singapore suggests that climate warming may not bode well for the short-lived tiny pollinators, as the projected increases in temperature expected for the tropics may shorten the lifespan of fig wasps by 33-60%. (Jevanandam et al. 2013). For an insect that already has a brief adult lifespan of just 1-2 days, this means a drastic reduction in the time it has to mate, locate a suitable fig, lay eggs and pollinate the florets. Over time, the reduction or absence of pollination services would lead to fewer ripe figs, and in turn both urban and wild animals may be adversely affected as they would lose a valuable source of food.

Figs in culture and cultivation

Unlike animals in the wild, people are luckier since most of the appetising figs that end up in our stores and on our plates are parthenocarpic, which means that the fig ripens on its own without pollination. Most of the figs commercially cultivated in California are of this type, while those in the Middle East are a combination of wasp-pollinated and parthenocarpic cultivars.

Due to their sweetness, nutritious value and abundant crops, figs play an important role as a food resource in many cultures around the world. Dried figs are an excellent source of minerals, vitamins and anti-oxidants. In fact, dried fruits are concentrated sources of energy, with each 100 grams of dried figs providing approximately 249 calories. Fresh figs, on the other hand, contain antioxidants such as vitamins A, E, and K. Both dried and fresh figs have a high calcium content and rank second after oranges in terms of calcium content in fruits.

Even today, figs continue to play an important role in food and nutrition. This is most evident during the month of Ramadan when Muslims from around the world including Singapore break their daily fast with a combination of figs, honey, dates, olives and bread.

In traditional Chinese medicine, dried figs are used as an ingredient in tonics to help strengthen the lungs and relieve coughs. In Western cuisine, dried figs are popular as healthy, energy-rich snacks like the fig newton, which is a widely consumed pastry roll filled with fig paste. Figs are also made into jams, preserves, biscuits and confections such as Turkish baklava. The dried leaves of one native fig, Ficus auriculata, can be used to make a medicinal tea

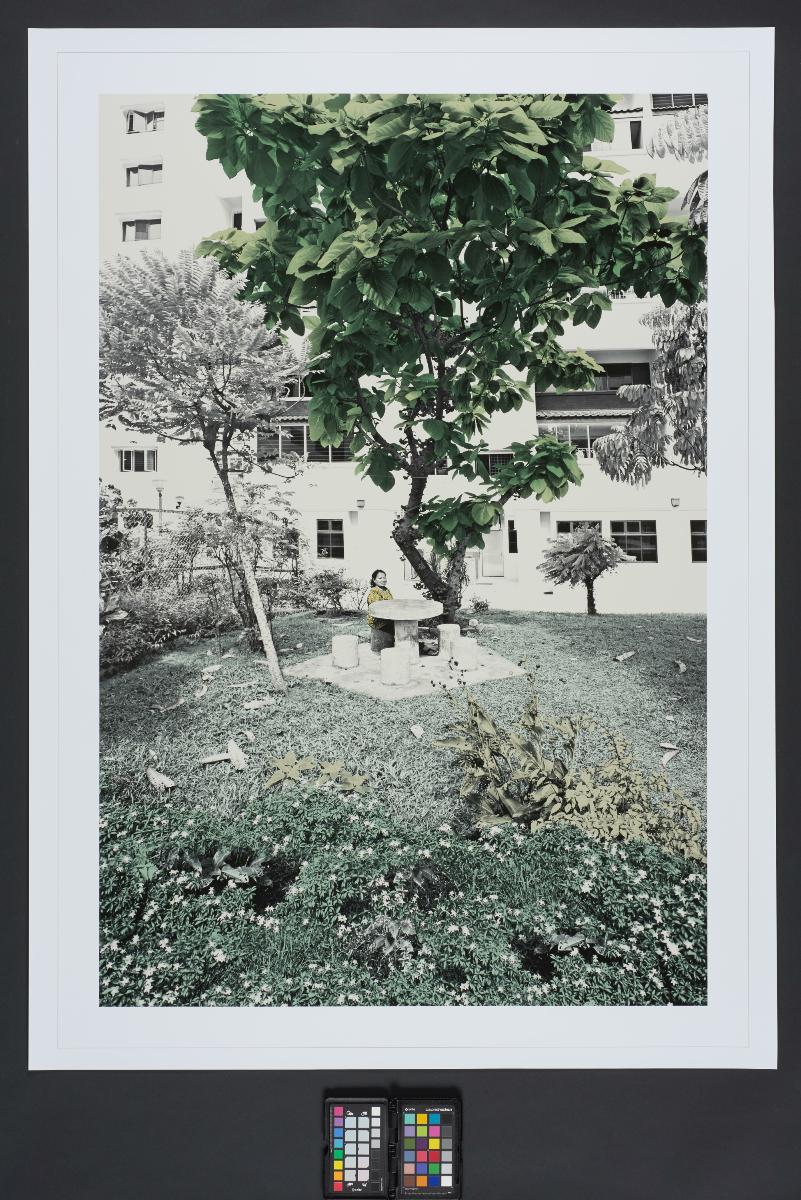

The fig’s significance does not just end with it being an easy-to-consume, nutritious food. These trees also have a strong religious significance in the East. It is said that Buddha found enlightenment while meditating under a Bodhi Tree, which is believed to be Ficus religiosa, a fig native to India but which has been introduced to Singapore. And so throughout countries where Buddhism prevails, like India, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Singapore, figs are revered and often planted as a religious symbol and worshiped in the absence of proper temples. When I was travelling in Thailand, a number of restaurants I dined at had a pressed leaf of Ficus religiosa on the first page of their menus, an indication of the deep-seated religious significance the fig tree holds in Thai culture.

But the bold, ubiquitous fig doesn’t hold back and has ventured beyond Islam and Buddhism into Christianity. It has been argued by some scholars that the forbidden fruit, which Adam and Eve consumed in the Garden of Eden, was the fig and not the apple. And that the leaves of the fig were used to cover Adam and Eve when they realised that they were naked. The most famous depiction of the fig as the forbidden fruit was painted by the Italian artist Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) in his masterpiece fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City.

Figs in various forms

Not all figs grow to become massive trees like the Banyan or Bodhi. Figs exhibit different growth forms that include climbers, shrubs, average-sized trees and large trees which reach well above the canopy. Many of these forms are found in Singapore. One large native fig tree is the Common Red Stem Fig (Ficus variegata), which can grow up to 40 metres high and is found mainly in parks and nature reserves. There is one specimen in the Botanic Gardens growing near the visitor centre, which can be recognised by the bright red figs growing in clusters from the trunk. Another native fig species, Ficus punctata, is a woody climber that can be found extensively along Holland Road on the side of Botanic Gardens. This species is easy to spot when it is figging as the figs look like oranges. A very common roadside shrub is the White-leaved Fig (Ficus grossu-larioides) which often attracts bulbuls, green pigeons, black-naped orioles and Asian koels among other birds. These species and more dot our urban landscape and provide sustenance for our urban fauna. As a result, the possible loss or reduced abundance of figs from the landscape should be of major conservation concern. Their value in our concrete jungle is perhaps most appreciated by local bird watchers and photographers who often flock to figging trees in anticipation of the huge variety of birds that visit these trees to feed.

Some of the figs found in Singapore are 120 to 160 years old as of 2013. Fortunately, the National Parks Board’s Heritage Tree Scheme, which began in 2001, identifies and conserves mature trees that are rare and have historical significance. There were 199 trees on the list in 2013, of which 34 were figs consisting of eight species. In particular, a 120-year old heritage fig tree at Sentosa Island was made a star when it received much media attention after being featured in a 2001 film, The Tree, starring popular local actress Zoe Tay.

And so it is, food, faith and controversy define the fig’s story, making it a ‘keystone’ in more ways than one. Like the roots of its own great Banyans, the magnificent Ficus in all its forms and habits has firmly intertwined itself into the lives of both people and wildlife. Given that more than half our 48 native species are endangered or extinct, no effort should be spared in conserving them. The next time you walk past a fig, take a moment to stop, observe the many birds, monkeys and squirrels that feast on its fruit, and appreciate how this natural bounty is the result of a complex yet fragile relationship with a tiny wasp that not many people have heard of and few have seen.

The Fabulous Figs of Singapore, which inspired this article’s title, is an excellent pocket book written by local fig enthusiasts. It provides a list of fig species found in Singapore with pictures, helpful descriptions and locations of notable trees. Available at good book stores, this is an informative little book I used when I first started out on my journey into the world of figs.

Dr. Nanthinee Jevanandam did her PhD research in figs at the National University of Singapore. She currently works as an Ecologist for AECOM, an environmental consultancy.

Notes