Text by Chua Mei Lin, Curator, Singapore Philatelic Museum

Images courtesy of the Thai Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia

Artefacts courtesy of Setia Darma House of Masks and Puppets, Bali

Stamp collection, Singapore Philatelic Museum

BeMuse Volume 4 Issue 1 - Jan to Mar 2011

In a land where the mystical and natural meet, nothing seems extraordinary. Masks take on supernatural powers and lizards grow big enough to swallow a goat without much effort. This is Indonesia or “Islands of the Indies”, a vast archipelago located at the crossroads of the traditional spice route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Land of Dance and Dragon was a discovery of Indonesia through its dances. This exhibition at the Singapore Philatelic Museum explored one of the greatest demonstrations of skill, art devotion and culture – the living tradition of dance. To portray characters and animals, performers don masks and elaborate costumes to narrate anecdotes of history, epic tales as well as current affairs. What started as a ritual performed for the gods to ask for protection against calamity still survives today. The dances, masks and costumes are diverse and varied but the quest for a peaceful life is common throughout the length of the archipelago.

“Islands of the Indies”

With a total land area of 1,919,317 square kilometres, Indonesia spans the equator between continental Asia and Australia and consists of over 13,000 islands, of which only 6,000 are inhabited. There are five main islands – Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Irian Jaya – and two smaller archipelagos: Nusa Tenggara and the Maluku Islands.

Stamps: Borobudur Ship Expedition

The country has over 240 million people speaking many regional languages and dialects and practising many of the world’s major religions. Trade thrived in this region as early as the seventh century. During the rule of the Srivijayan (CE 700 – 1300) and later Majapahit (CE 1293 – 1500) empires, Indonesia traded with China and India. Through the same channels, Hinduism and Buddhism were introduced. Around 13th century, Islam arrived with Arab traders. European countries fought among themselves for control of the spice islands of Maluku. Dutch colonial powers (CE 1602 – 1942) then ruled Indonesia for three and a half centuries till after World War II.

Indonesia displays an amazing array of cultural forms. It has been said that in Indonesia – art and life are intertwined. To observe the formal study of dance is to understand the history and culture of the country: its music, religion, literature, sculpture and architecture. Indonesian culture is a rich blend of heritage, living tradition and modern art. Monuments provide the built heritage. Traditional theatres of shadow puppets or human actors form the living tradition, and contemporary painting, sculpture, drama and dance inject modernism.

Dance – A Living Tradition

Dance in Indonesia serves as more than entertainment and recreation. Many dances have a religious significance. They are performed to honour ancestors, in traditional ceremonies like weddings, births and deaths as well as yearly activities like harvesting. There are as many dances as there are provinces in the country. Within each province, there are many types and variations of dances. Although the dances mentioned here are but a small selection, their importance to the fabric of society cannot be denied.

Traditional ceremonial dances are still practised in Bali especially during the Galungan and Kuningan festivals. Galungan is a Balinese holiday that occurs every 210 days and lasts for 10 days, whereas Kuningan is the last day of the holiday. During this time, the Balinese gods are believed to visit the Earth. In Kalimantan, the Dayak people perform the tari mandau (sabre dance) which mimics the trailblazing action of clearing the forest. This dance which symbolises the fighting spirit of the people are performed during special ceremonial days. The Sanghyang trance dance is presented in Bali to ward off evil spirits. Java has a similar trance dance called Kuda Kepang.

Origin of Dance in Indonesia

It has been said that before the introduction of formal religion, the gods had powerful influence over the land and people of Indonesia. To induce the gods to answer their prayers, sovereigns proffered fresh flowers and fragrant incense. But the most refined offering is the gift of dance. Indonesian dances can be divided into three broad types: traditional religious dances, dramatised dances, folk and modern dances. Traditional religious dances are based on the belief that the dance would help people make contact with the gods, provide meaning to life or instill a force into things such as crops, fertility or war.

Gambuh is considered the oldest form of dance drama and the source for other dramatic dances. It was performed in the Javanese courts of the Majapahit kingdom and belongs to the semi-sacred or ceremonial group. The stories are usually drawn from the lives of the kings of East Java, very often from the Panji stories. Panji was a prince famed for his search for his beloved Princess Candra Kirana.

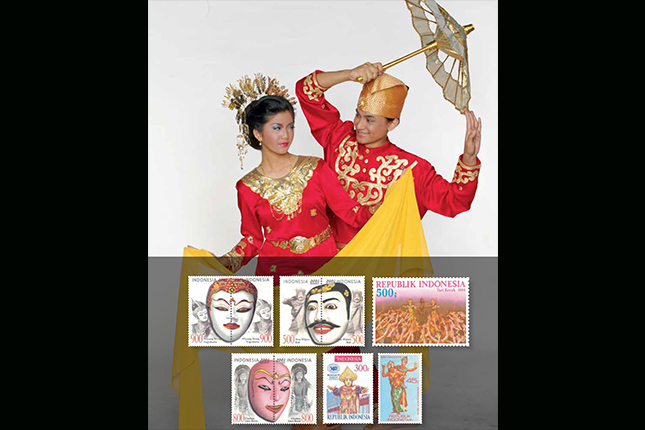

For about 100 years during Dutch colonial rule, dance lost its importance. After the country gained independence, a desire to express a sense of freedom and democracy prompted the revival of folk and regional dances. Society dances such as the ronggeng of West Java, the handkerchief dance and umbrella dance of the Bugis are primarily for entertainment and have no religious significance. On the other hand, the mask dance is one of the oldest traditions in Indonesian art and exists in almost every region. Many evolved from religious customs and rituals while others are purely for artistic pursuit.

Dances of Java

Yogyakarta and Surakarta, where the kraton (palaces) are located, are famous for the refined and graceful Javanese dances. There are several groups of dances from this region: the Wayang dances originally intended for ritual ceremonies; the sacred Bedojo and Srimpi court dances; the Beksan or War dance; and the dances of the villages.

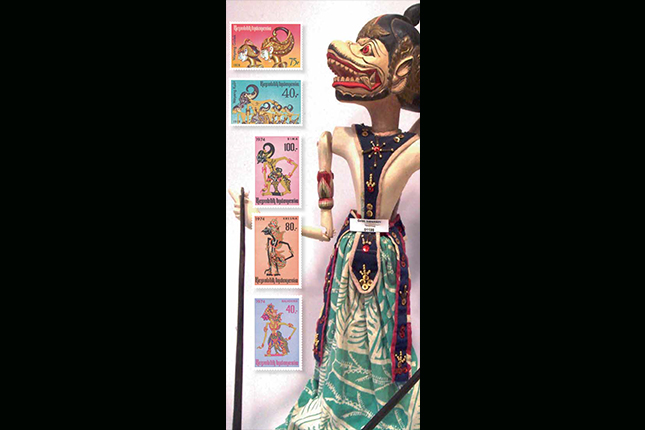

The word ‘wayang’ means shadow. Originally wayang was performed by the head of the family to ask the spirits for guidance for important events like marriage and birth. With family members as witnesses, spirits were said to appear as shadows. Nowadays, current events, rules of behaviour and education form the basis of wayang stories. The different types of wayang include Wayang Kulit (leather puppet) Wayang Klitik (flat wooden puppet), Wayang Golek (wooden puppets) and the non-puppet ones of Wayang Beber (which use paper parchment as a backdrop) and Wayang Wong (human masked dances). The wayang stories are usually based on the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics.

Stamps: Wayang Golek and Wayang Kulit on stamps

Wayang kulit is a shadow puppet performance and is an integral part of temple festivals. The puppets are made of flat dried buffalo hide. The performance area has a screen and a light (an oil lamp in older days) and in front of the screen sits the Dalang or puppeteer, who conducts and plays the entire wayang. In front of him lie banana tree stems where the puppets are stuck when not in use; bad characters on the left and good ones on the right. At the start and end of the performance, the dalang will place the gunungan in front of the screen. The stage represents life on earth. The dalang symbolises God, the screen is the universe and the banana trunk where the puppets rest is earth. Hinduism first arrived in Indonesia followed closely by Buddhism in the early centuries. The Hindu influence is evident in the shadow puppet stories with themes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

The Gunungan or Kayon is used to start and end the play, as well as change one scene to another. It represents the Tree of Life and the unity of the cosmic order. Two gatekeepers stand on both sides of the door to the spiritual temple. There are many versions of the gunungan depending on the local culture and social situation. Javanese gunungan have more symbols compared to those from Bali.

Bedojo, began within the walls of the courts of Jogjakarta to mark ceremonies like the sultan’s birthday and special anniversaries. It is performed by girls from the aristocracy. The Bedojo is a slow and deliberate dance performed by nine girls with faces made up like a traditional Javanese bride. On their heads they wear a diadem with a white bird feather. The Srimpi is similar to the Bedojo but less grand and performed by four women. Beksan or War dances are performed by pairs of men and women who retell the stories from some segments of Javanese literature. Away from the courts in the villages, people perform dances such as Ronggeng, Djoged, Handkerchief Dance, Reog and Kuda Lumping, some as courtship dances and others as celebratory dances.

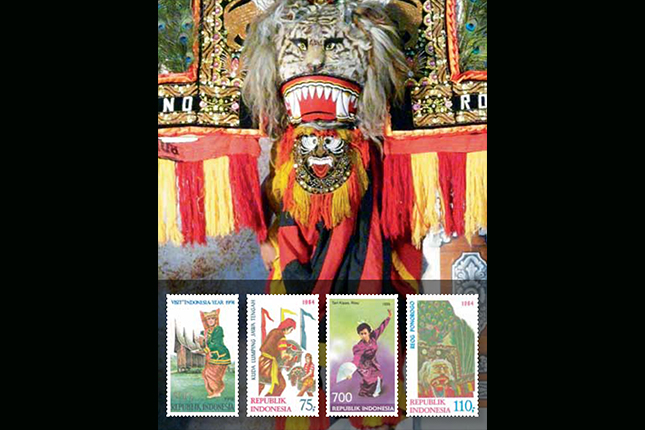

Stamps (from left): Saucer dance, Kuda Lumping, Fan dance, Reog.

Dances of Bali

Music and dance are integral to religious ceremonies and social activity of Balinese life. This island has one of the most intriguing selections of dances. In areas where people practise Buddhism and the Bali-Hindu faith, spirits are often summoned to enter living humans and puppets. This is especially evident in the Sanghyang and Barong dances. The Sanghyang is a trance dance ritual where pre-adolescent girls perform under a hypnotic influence. This dance is performed to ward off disasters or epidemics.

Kecak is probably the most recognisable Balinese dance. With an all-male chorus chanting “cak, cak, cak” in overlapping sequence, the effect is both hypnotic and mystifying. The Kecak is a vocal chant originating from the Sanghyang dance. The Rejang is a sacred dance performed in the inner court of the temple during offerings and celebrations. It is a group dance by pre-adolescent girls, unmarried or older women. They are said to be heavenly maidens who have come to earth.1 The male equivalent is the Baris Gede or warrior dance.

Stamps (clockwise from top left): Wayang Wong, Arsa Wijaya, Kecak, Tambulilingan (bumblebee) dancers, Baris Gede dancer, Cirebon.

Balinese mask dances have existed for over a century. Like the older types of dances, mask dances were used to drive out evil spirits that could cause havoc to crops. Prayers are said at every step of the mask preparation, from the selection of the tree to the performance. Bali’s Topeng dance-drama often portrays stories based on the lives of the Balinese kings. Early masks have mouthpieces which the actor bites to hold the mask in place. Today, the masks are tied to the face.

Topeng Pajegan is a monodrama as all the roles are portrayed by one dancer. The stories are usually derived from the chronicles of the kings. Depending on the occasion: wedding, tooth-filing ceremony2 or birth, the performer will choose the story most appropriate for the occasion. The characters appear in a fairly typical sequence. The Patih, a minister of strong character with a red face indicating bravery is first to appear. He is usually followed by a coarse brown face Patih and then a wise old man (Topeng Tua).

The last character to appear is Sidhakarya3. After he gives offerings and prayers to the gods he immediately gives chase to the children in the audience. When he catches a child, he carries him to the shrine and holds him up to the gods. The child is then released and rewarded with a small gift of Chinese coins, as a symbol of prosperity. In current times, the Sidhakarya segment does not happen very often.

The Topeng Panca is performed by five dancers during temple festivals. The full mask characters such as the king and ministers do not speak but deliver their ideas through elegant and graceful movements. Half-masked characters like the clown servants tell the stories.

The Barong is a mythological creature that performs stories that are entwined with black magic and some form of trance. With its big eyes, clacking mouth and furry body, it patrols the village streets clearing away dark forces that bring harm to the land and people. Rangda with her fearful mask is the witch-widow and Queen of Black Magic. She is portrayed with a long hanging tongue, fangs and long hair. In the magical Calonarang dance, the Barong and Rangda characters are pitched against each other in a classic battle between the good and evil.

The creation of wayang wong was initiated by Dalem Gede Kusamba, ruler of Klungkung from 1772-1825. He commissioned a new dance based on the Ramayana epic using a collection of royal masks. Following the wayang kulit style, wayang wong was created with human performers instead of puppets. Wayang wong is performed during the holy days of Galungan and Kuningan. As the masks are sacred, they are kept in the temple and are blessed before and after use.

Dances of Sumatra and other Islands

In Sumatra, the influence and presence of ancient dances are less evident because the faster paced and social dances are favoured. There are fewer Ramayana and Mahabharata themed dances except around the areas of Batak and South Sumatra. Dances which originated from the worship of the various gods are still performed although the region’s prevailing customary law (adat) and religion now cast an overriding influence.

Dance and the Dragon

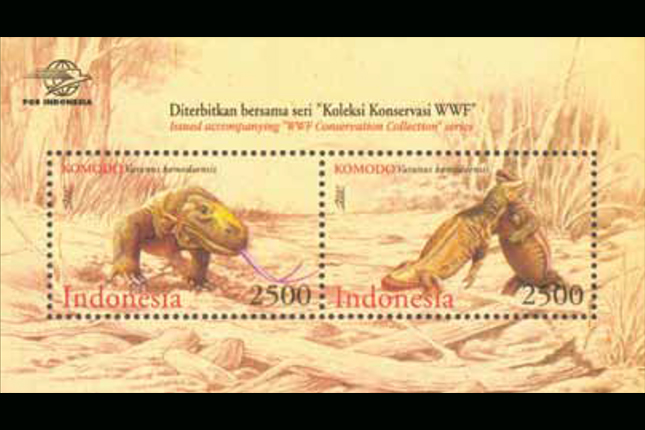

The huge Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) lives in a hostile environment with little food and water. It overcame all these challenges and remained fairly untouched by evolution and the Ice Age. The existence of the Komodo dragon is proof of its tenacity.

The prehistoric-looking reptile serves as a perfect foil to the refined dance. The reptile’s appearance is beastly, it walks with an awkward gait and displays an amazing instinctive power when it attacks. The dance on the other hand has graceful and refined movements and the technique is acquired through many years of strict training. The Komodo dragon commands respect in its environment and the dance pays reverence to the gods. Although the elegant dance and the awkward Komodo dragon seem worlds apart, there is an interesting link between them. Note the posture of the dancers – the limbs, body, neck and head – with many movements involving raised elbows, and angled torso. Observe the Komodo dragon’s swagger, every step taken with limbs at an angle. Is it pure coincidence or a case of art imitating nature?

A ‘fire-breathing’ Dragon

The fire-breathing dragons as told by ancient mariners who visited the Spice Islands are in reality Komodo Dragons. They are the largest living species of lizard. These venomous lizards can grow to a length of two to three metres weighing about 150 kilograms. Komodo National Park is located at the Lesser Sunda Islands which covers the larger islands of Komodo, Rinca and Pada. Founded in 1980, the national park is also a popular location for scuba diving as the marine biodiversity includes whale sharks, manta rays, pygmy seahorses, sponges and corals.

Notes